This article has been written by Makrand Chauhan, pursuing the Diploma IPR, Media and Entertainment Laws from LawSikho.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Over the last year, we have been relying on intermediaries of various kinds more than ever before. Just as much as these intermediaries have given us all the facilities necessary to collaborate and communicate with each other, at other times, the environment that they created, ended up being abused by various actors. These abuses ranged from violation of criminal law to breach of personal rights, including infringement of intellectual property.

What are the challenges that we face and what are the safeguards that should be taken in order to ensure that we preserve the right balance between the private proprietary rights and the public interest is something what needs to be explored? This article relies heavily on the taxonomy that was set out in J. Riordan’s book on the liability of internet intermediaries and ideas put forth by Prof. Althaf Marsoof in his various book chapters related to internet intermediary liability.

Intermediaries : definition and importance

Intermediaries are nothing new. We have known intermediaries since time immemorial (even before the internet). Traditionally, acting as a linkage in market distribution systems, intermediaries provide benefits like ease of access to buyers, assistance in standard-setting, enabling ‘comparison shopping,’ etc. Intermediaries could be middlemen distributors, or financial intermediaries, which usually enter into a long-term commitment with producers and facilitate in selling goods and services to its consumers in a systemic and accountable manner. In the same line, internet intermediaries also ‘facilitate’ the use of the internet and its related products & services. They typically include internet service providers (ISPs), search engines, and social media platforms. They seldom include online shopping platforms like Flipkart, Amazon, etc.

Now, what was significant when the internet had started blooming in the early ‘90s is that people had started talking about ‘disintermediation.’ There was a belief that the internet would eliminate the need for intermediaries themselves. But, in reality, what happened was quite the opposite. We saw not only the traditional intermediaries getting into the online sphere but also new types of intermediaries emerging from time to time. Thus, in essence, the internet itself ended up giving rise to mushrooming of different types of intermediaries. But when we are trying to deal with the subject of intermediaries and thinking about the question of how to make the most out of them to enforce the law, it bodes well to have an in-depth understanding of their technology functions as well as their place in the hierarchy of the online world.

Riordan’s book gives an apt understanding of where the different intermediaries that we come across on the internet are. According to him, there are mainly three layers, viz., the physical infrastructure, that we may or may not see because it is provided for in various specific, specialised places that we hardly come across. Then, the network layer which provides us with the much-needed connectivity. And ultimately, what Riordan refers to as the ‘application layer, which is what we most interact with and largely consists of the online search engines and ISPs. Thus, according to Riordan, we first need to locate where the intermediary is before deciding upon the kind of responsibility that we can vest upon them.

Why focus on intermediaries?

There are many reasons why we might want to focus on intermediaries, particularly when it comes to enforcing the law and private rights. One of the main reasons from the economic perspective that is often cited is that these intermediaries are the cheapest cost avoidance. Justice Arnold in ‘Cartier v. Sky’, the first-ever case in which an injunction was awarded against an ISP to protect trademark rights in the UK, had said that it is economically more viable to require intermediaries to enforce our rights as opposed to getting the right holders to do the same in an online environment. This decision was one that was considered from an economical cost perspective. There were many reasons for the same which have been very briefly setting out as follows:

Cost-effectiveness

Economically speaking, it is less expensive for us to litigate against or seek the assistance of intermediaries as opposed to going after individual infringers. This is so because while it is very easy for us to identify relevant ISPs that can provide services that may be used for various infringements, it still gets increasingly difficult for us to find and identify individual infringers because of the relative anonymity that the internet tends to provide.

Intermediaries as choke-points

If all of us were to get access to the internet or use the internet for a certain purpose(s), we would need to make use of some kind of service provider because we simply don’t have the finances or the infrastructure to do so ourselves. Thus, all of us need to go through one or the other intermediary, and therefore, it makes sense to employ these intermediaries to assess the legality of content that is transmitted or disseminated through them. It can be argued that these intermediaries have more control over the relevant content, infringing or otherwise than we have over such content. So, it makes sense for us to utilize them for the purposes of enforcing our rights.

The ripple-effect argument

If we find that there are multiple infringements being committed around the world, it is simply going to prove quite burdensome for us to take action against individual cases of infringement. One would rather isolate the intermediaries involved as opposed to wasting time and energy going after every instance of infringement. Thus, there is great utility in focusing on intermediaries from the rights enforcements’ perspective.

A note of caution

Lichtman and Posner have suggested that we must be cautious before determining which intermediary should be held responsible for enforcing our rights or taking on liability for infringements. The reason is that while it is true that these intermediaries do provide the infrastructure or the environment within which various kinds of infringements take place; from a purely cause and effect point of view, one might argue that but for these intermediaries, infringements would not have taken place in the very first place. Thus, there is indeed legitimacy in holding them accountable. But, be there as it may, from a practical perspective, we still need to think hard before pointing at a particular intermediary to either enforce rights or engage in various policing or surveillance activities.

Although it might make sense to use intermediaries to detect certain types of content like viruses, spam, or any malicious software because of their certain kind of inherently identifiable traits, when it comes to things like IP infringement or content that could potentially infringe IPR, we must look at the need to exercise human judgment over it. We would need to apply a series of laws and legal principles in relation to complex facts. Either there could be certain differences involved, such as fair use, or independent rights, such as free speech, might also come into play. Thus, because of these complexities, it could be quite dangerous to vest these private actors with no ‘constitutional accountability’ to determine the rights of individuals. At the same time, we need to think twice before we empower these intermediaries to engage in such activities simply because it may be more complex and difficult for them to discern between lawful and unlawful content, particularly in the area of IP (and other private rights).

Implications to third parties and collateral damage

When we require these intermediaries to engage in an exercise of removing content or employing various tactical measures to deal with an infringement, there may be unintended consequences that might come into play which could result in collateral damage. There might be some impact felt when it comes to legitimate activities. Thus, we need to make sure that when intermediaries are employed for the purpose of IP enforcement, legitimate third-party activities are not hindered by these efforts. Hence, a certain level of precaution is supposed to be observed while engaging intermediaries for IP enforcement.

Early developments

A look at related US cases

Before the DMCA and other laws which deal with intermediaries in various contexts, there were certain developments that led, in particular, the US Congress to react a certain way. The Bulletin Board cases: A bulletin board service, a forum where the content was put up to be viewed by its subscriber, was found to be directly liable for copyright infringement.

- In Playboy v Frena (1993), someone had uploaded some content in which copyright subsisted which was downloaded by many people whereas Frena was merely a platform that provided hosting service but didn’t engage in a kind of activity that violated any copyright.

- In a similar setup in Sega v. Maphia (1994), Sega Games was also a sharing platform but in Mafia, they were more involved in infringements. However, during an injunction hearing, the judge decided that there was a prima facie case for direct copyright infringement which suggested that despite being a mere intermediary, the platform was suddenly caught up in primary copyright infringement.

- In Religious Technology Center v. Netcom (1995), all of these things were settled. However, the Netcom case also let it open that there might be a certain degree of secondary accessorial liability on the part of intermediaries where their services are utilized for copyright infringement.

Clearly, what was happening before the advent of DMCA and the other related laws were enacted is that there was an increasing trend of internet intermediaries getting entangled in litigation for the services they were provided in respect of certain forms of infringement. However, many legislators soon realized that this trend was not very conducive to the development of internet technologies at that time. There was a growing sense of concern about how this increase in liability would impact the development of the internet and intermediaries.

Legislative approach to these issues in the US

With the aforementioned reasons in mind, the US Congress enacted two important pieces of legislation:

US Communication Decency Act

It resulted in the intermediary becoming completely immune from any kind of liability with respect to the content that would be transmitted on their platform. But this immunity was not extended to IP infringement and in respect of certain areas of criminal laws. For that reason, when it came to IP (mainly copyrights and trademarks), intermediaries still remained open to the threat of being prosecuted for infringement. Thus, while scholars and critics hailed Section 230 of this Act as the savior of freedom of speech, many among them argued that a blanket immunity wasn’t really the best idea because then they won’t be motivated enough to police their network.

US Digital Millennium Copyright Act

For the first time, the provision of safe harbor was set up for intermediaries under this Act that could potentially get entangled in copyright disputes. Liability under the DMCA is primarily based upon the intermediary’s knowledge of a given infringement, its control over the means of infringement, and its failure to remove the infringing material after having acquired the knowledge of the same.

In the US trademark context, however, there isn’t any statute that mirrors the DMCA, which seems to be quite an interesting disparity. Although in the EU, Articles 12 to 15 of the e-commerce directive granted conditional immunity to service providers in respect of all areas of law across the board, some developments were observed in the trademark context through some judicial innovations, and a similar regime was developed through the Inwood Laboratories Inc. formula which was then modified to apply to the online context which essentially replicated what one could find in the DMCA.

The practice of notice and takedown

The interesting part of the phenomenon discussed above is that since the liability of intermediaries was based upon the knowledge of infringement and their failure to take steps to remedy or eradicate these infringements, it basically gave rise to the practice of notice and takedown. Thus, if a copyright owner or a trademark proprietor sees a violation of their rights on a popular online platform like Facebook or YouTube, then s/he can send the relevant intermediary a notice of infringement, and once it is served, they would have the requisite knowledge and would need to address the infringement expeditiously. Failure to do that would then eventually open them to liability. The good thing about this is that it is very efficient, and without the need to go to court, one can simply serve a notice, which is low-cost and time-saving.

The only problem with this approach is that it is extra-judicial which means that there is no determination by a judge or an independent administrative body regarding whether or not the content that has been identified in the notice of infringement is actually infringing or not. That determination is made by the intermediary itself.

The issue with notice and takedown

It needs to be noted that most of these are private actors usually driven by economic interests, and their interest lies in avoiding liability at all costs. Therefore, some scholars have seriously questioned whether or not notice and takedown is a conducive approach to reaching a balance in the enforcement of IP rights, viz-a-viz third-party interests. Wendy Seltzer has been very vocal about this and has gone on record to say that the DMCA is responsible for the restriction of internet speech because of the incentive structure that it creates for the online intermediaries. Another scholar Julie Adler says that one practical result of Notice & Takedown provisions is that intermediaries which enforce them fail to account for whether a particular user-generated work is a fair use or not.

There have been a few studies that have gone into this from an empirical perspective. The most interesting among which has been the Urban-Quilter study because they considered over 800 notices that Google had received and found that approximately 30% or more of these notices were having problems with them and that they raised questions which should ideally be decided by a court of law. It was not appropriate in their view that these notices or the legal issues arising from these notices were being determined by private actors.

EU DSM perspective on notice and takedown

From a legislative point of view, there is also a shift that can be witnessed, most comprehensively in Article 17 of the EU Digital Single Market Directive, which expressly states that when online content-sharing platforms provide access to copyrighted works on their platforms, they are to be regarded as committing acts of communication to the public for making them available online as such. This is basically telling us that if the works that these intermediaries are disseminating or making available to the public happen to be infringing content, then they would be regarded as having been communicated to the public, which is a right exclusively vested in the copyright onus. Thus, what this article is doing is treating intermediaries as potential primary infringers.

In the early 90s, before the intermediaries could share and disseminate things to the public, they had to obtain the requisite authorisation from the copyright owners, etc, and only then, were they able to provide. Thus, in accordance with high industry standards of professional diligence, they must make best efforts to ensure the unavailability of specific works and other subject matters for which the right holders have provided the relevant and necessary information. So, they must make best efforts to ensure that works in respect of which they have been given notice of any infringing work in relation to those works do not come onto their platforms by the way of uploads or any other similar means. The provision goes on to say that they must act expeditiously if they receive the notice of infringement and also make best efforts to monitor their platform, thereby preventing future uploads of such contents. What’s interesting to note here is that the provision itself does not say that you must use automation, but the crux of it is that it seems to be the only way to achieve or meet the requirements of Article 17.

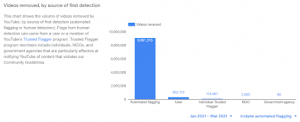

Many scholars have voiced their concerns about this. In fact, the graph below is a reflection of the use of automated technologies to remove content ex-ante before their legality is even determined by any judicial body or administrative authority using automated means. Within the span of April to June 2020 last year, over 11 million videos have been removed using automated techniques by YouTube, which is a significant amount for that period of time. Removal of content which resulted from a user sending a notice of infringement is much less when one considers in comparison in this graph.

Suggestive remedies

Injunctive relief

An approach that is much safer because of the outcomes that might be reached as it is a judicially supervised approach, is one of injunctive relief. There are many cases that have already been filed in the courts of the US, EU, Australia, and India where copyright owners and even trademark proprietors have sought an injunction against internet service providers so that certain websites that are flagrantly infringing or those which contain counterfeit goods are either removed or at least, the access to them for users is blocked. While the challenge is that the infringement persists even though people don’t have access to it, the good thing about the approach is that it goes through the scrutiny of courts.

Dynamic injunctions

In India, in the case of UTV software, for the first time, a dynamic injunction was issued. When a particular website is blocked, its operator essentially tries to move that website to a new address to circumvent the blocking in terms of technical impact. Dynamic injunctions essentially allow the relevant IP proprietor to require the ISP to update the technical measures so that these measures extend to all of these instances of infringement of a particular website that might arise in the future because of the circumvention on the part of the website operator. Thus, instead of going through the whole process of litigating all over again, the technical side of things is updated so that the new website is blocked as well.

While in Singapore and the UK, right-holders can do this without going back to court, they can simply inform the ISP, and they can require the ISP to block the new location. But, in India (and, probably in the roadshow case in Australia) if the website operator decides to shift the location, one still needs to come back to the court, the case needs to be accessed and once there is a new order by the judge, then one has to implement it by updating the technical measures. This approach is better because it is much safer in terms of ensuring that one doesn’t proceed without appropriate judicial supervision. However, given the very well-known tradition of delays in the Indian judicial system, it is given to much speculation on whether a court might really want to burn itself with having to entertain these kinds of applications which probably might overwhelm the court system.

Conclusion

The remedies suggested above are what we may consider and utilise to find ways of dealing with enforcement of IP rights and making use of intermediaries for our most valuable purposes. Apparently, when it came to website-blocking injunctions, the most relevant Indian statutes like the Copyright Act, 1957 and the IT Act, 2000 were found to be mute. Due to this, the Delhi High Court, in its related decisions, had to import the fundamentals of proportionality and effectiveness from European law. Also, it should be helpful to know that the US Supreme Court, in the Inwood case above, made it amply clear that special rules should apply to parties that might not be violating IP rights but could end up facilitating others’ infringement anyway.

To conclude, intermediaries are hardly our adversaries. We recognize, interact with and rely upon them continuously throughout our everyday lives, and we need to make proper use of them to ensure that our rights are protected. However, we must do so within a very certain and specific legal framework that provides for safeguards and ensures that third-party interests and rights are protected at the same time.

References

- https://hbr.org/2014/06/mastering-the-intermediaries

- https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-liability-of-internet-intermediaries-97801987

19779 ?cc=us&lang=en& - Dynamic injunctions against Internet intermediaries: An overview of emerging trends in India and Singapore

- https://singhassociates.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/SA-IP-Tech-Jan-2020.pdf

Students of LawSikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals, and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications