This article has been written by Srishti Singh, pursuing Certificate Course in Introduction to Legal Drafting: Contracts, Petitions, Opinions & Articles and has been edited by Oishika Banerji (Team Lawsikho).

This article has been published by Sneha Mahawar.

Table of Contents

Introduction

When a person commits an offence, he is subjected to the various applicable laws. Subsequently, he is convicted and the trial commences. Resultant of the proceeds is the issuance of a sentence. Execution of such sentences implies that the court shall cause any order to be carried into effect by issuing a warrant or taking such other steps as may be necessary. In India, the execution of a death sentence is governed by various sections of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. Suspension of a sentence refers to a temporary postponement of a sentence, whereas remission means decreasing the period of the sentence without changing its character. Conversely, commutation implies substituting a more severe form of punishment with a less severe one. Unlike remission, a commutation changes the character of the punishment. Suspension, remission and commutation of sentences are governed by Article 72 and Article 161 of the Indian Constitution, whereas Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 has a complete Chapter, Chapter XXXII dedicated to them. However, execution, suspension, remission, and commuting of sentences, depend on several variables, administrative and judicial powers combined, which are covered in more detail below.

Capital punishment

History

To say the least, capital punishment is as old as time. Death penalty was frequently used until the nineteenth century, even for minor offences. The importance of humanity and justice was only acknowledged when the world was divided into nation-states. In the Indian context, as per the original Code of Criminal Procedure of 1898, the execution was the norm for murder convicts. If the judges were to award life imprisonment for the same, they had to give specific reasons to do so, in writing. However, this requirement for a written reason was removed later by an amendment to the CrPC in 1995.

Henceforth, this amended position was enacted in the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC). Life imprisonment became the norm and the death penalty was to be awarded only in exceptional cases and required ‘specific reasons’.

The rarest of the rare doctrine

Death penalty is a hotly debated topic over numerous legal spheres. This is because it evolves serious moral, legal, and ethical questions. Several human rights organisations contend that capital punishment is directly at odds with Article 21 of the Indian constitution, which guarantees the right to life to every citizen. The Article states that “no person shall, except and there the procedure prescribed by statute, be deprived of his life or personal freedom”.

Under IPC, a death sentence is provided for criminal penalties, namely criminal conspiracy, murder, the war against the government, mob-blowing, and killing dacoity including the war against the government. However, the Constitution has provided for mercy on the death penalty by the President of India.

In Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980), Bachan Singh was tried and convicted, and sentenced to death under Section 302 of IPC, dealing with punishment of murder. A serious question of the constitutionality of capital punishment under Section 302 was raised therein, to which the court contended that capital punishment ought to be granted in the rarest of the rare cases.

Moreover, the Law Commission of India summed up in its 35th report to the Government of India in 1967 that “Having regard, however, to the conditions in India, to the variety of the social upbringing of its inhabitants, to the disparity in the level of morality and education in the country, to the vastness of its area, to diversity of its population and to the paramount need for maintaining law and order in the country at the present juncture, India cannot risk the experiment of abolition of capital punishment. Moreover capital punishment does act as a deterrent. Basically every human being dreads death.”

Execution of a death sentence

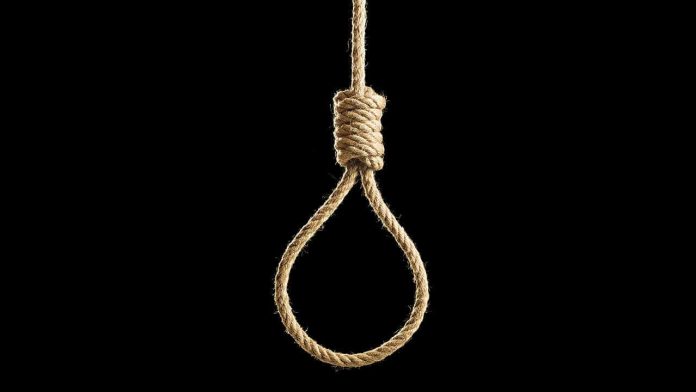

Execution of a death sentence is done in various ways in different countries including hanging, beheading, shooting, lethal injection, stoning, electrocution and gas inhalation, and Inert gas asphyxiation. In India, execution of a death sentence of either done through hanging(under IPC) or by shooting (under the Army Act, 1950)

Such execution may be carried out by passing an order either by the sessions court (while compulsorily obtaining the high court’s authorization) or by the high court itself, in the rarest of the rare cases- (Bachan Singh vs State Of Punjab (1980))

Exceptions to capital punishment in India include minors, pregnant women and intellectually disabled. These offences are punishable by death in India.

Suspension, remission and commutation of sentences

Origin

In the words of H M Seervai, “Judges must enforce the laws, whatever they are, and decide according to the best of their lights; but the laws are not always just and the lights noy always luminous.”

Article 72 and Article 161 of the Indian Constitution govern the suspension, remission, and commutation of sentences. The origin of the pardoning powers possessed by the head of the state in India stems from the colonial era in which the British crown was given a prerogative of mercy. The Government of India Act of 1935 gave the British crown the right to grant pardons, reprieve, respites, or remission of punishments. In the Indian context, the power to pardon is not a private act but rather is a part of our constitutional scheme. When justice gets lost in undue harshness or evident mistake in the operation of law, executive clemency affords the much-deserved relief.

Relevant provisions dealing with suspension, remission and commutation of sentences

Article 72 says that the president shall have the power to grant pardons, reprieves, respites remissions of punishment or to suspend, remit or commute the sentence of any person convicted of any offence. A similar kind of power is given to the Governor of a state under Article 161. The President, as opposed to the governor, can nevertheless, offer pardons even when the accused is given the death penalty. Another distinction is that, in contrast to the governor, the president may give mercy when the sentence has been passed down by a court martial.

While the governor offers pardons when the accused has broken a state law, the President only does so when the accused has broken a union law. In addition to these constitutional guarantees, Sections 432, 433, 433A, 434, and 435 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973, also include pardoning provisions. Section 54 and Section 55 of the IPC gives the competent authorities the authority to commute a death sentence or a life sentence in accordance with its provisions.

In Maru Ram vs. Union of India (1980), the court observed that political vendetta or party favouritism cannot but be interlopers in and will vitiate the exercise’, which is quite logical, considering that this executive power can easily be exploited to further political vendetta. Further, in Kehar Singh vs.Union of India (1988), when the President declared to accept the mercy petition of Indira Gandhi’s assassin, Kehar Singh, the court rightly stepped in and said that Article 72 doesn’t fall outside the judicial domain and is well subjected to judicial review. But, to not overtake its judicial duties, the court emphasised that judicial review of the order of the president cannot solely be done on its own merits except within the strict limitation laid down in Maru Ram. What are these limitations, one may wonder? The court provided that the pardoning power can be subject to a review where an executive decision has been made on altogether irrational, arbitrary, unreasonable, or malafide grounds such as discrimination based on religion, caste, colour, or political loyalty.

Impact of capital punishment

Advocates of capital punishment defend it on the presumption that it sets a good example of justice in the society and further deters the commission of heinous crimes. Moral arguments include contentions that it is one such practice which sets the perfect balance between good and evil in society.

Society has a moral and legal obligation to protect the lives of its dwellers, and murderers, who threaten them are convicted by the means of capital punishment. We assume quite broadly that in certain circumstances, execution is the only way to guarantee that such individuals won’t commit atrocious acts again. Capital punishment supposedly saves society from premeditated murders.

But, there is no evidence to substantiate these claims. No evidence whatsoever exists to prove that capital punishment is a far superior deterrent to violent crimes than say a less severe alternative, like life imprisonment.

The pardoning powers

Execution, suspension, remission and commutation of sentences are no doubt an intricate part of the judicial scheme. They are crucial correctors of judicial errors and establish a humane approach to the system. They instil virtues like forgiveness and perseverance and promote the prisoners’ rehabilitation and betterment. However, certain cases like the release of Bilkis Bano convicts do question the righteousness of this power to pardon and here the power of judicial review comes into light.

Conclusion

While there exists no proof that the death penalty prevents the future commission of crimes, it however imposes a grave cost on the society. Locking criminals away achieves the same goal as the death penalty and does not even require taking another life. On the contrary to saving lives, the death penalty indeed cheapens the value of human life. Valuable human resources who could have been rehabilitated are lost to capital punishment. Moreover, juries make mistakes! Death penalty imposed on innocent people wipes away all hopes of undoing the injustice done to them. Therefore, as a society, we truly need to reflect on whether the death penalty is indeed our duty or our doom? Furthermore, power to pardon granted by the Indian legal system serves as a ray of hope for such death row convicts and thus sets a more just judicial system into practice. Thus, concluding in the words of Pathak, C.J., “in any civilised society, there can be no attributes more important than the life and personal liberty of its members” and the pardoning power of the President and the Governor is one such power which ensures the same. This power is thus an imperative and integral part of the Constitution and it is hoped that the repositories of the power exercise the same in a just and impartial manner and the judiciary continues to act as a watchdog in such cases.”

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals, and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications