This article is authored by Titas Biswas, where she has discussed the importance of the Indian Constitution, the rights conferred by it and the remedies on their infringement. She has also discussed writs, its kinds, and related provisions in the Indian Constitution and explores its contribution in the Indian legal system.

Introduction

The Indian Constitution confers certain rights upon its citizens. It also guides the non-citizens on a path to remedies in cases of infringement of their rights through the embodiment of Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, which safeguards fundamental rights of the non-citizens. By constitutional rights, it is inferred as the rights mentioned in Part III of the Indian Constitution, which provides for ‘fundamental rights’. The legal maxim ubi jus ibi remedium fits well in this aspect, which preaches where there is a right, there is a remedy.

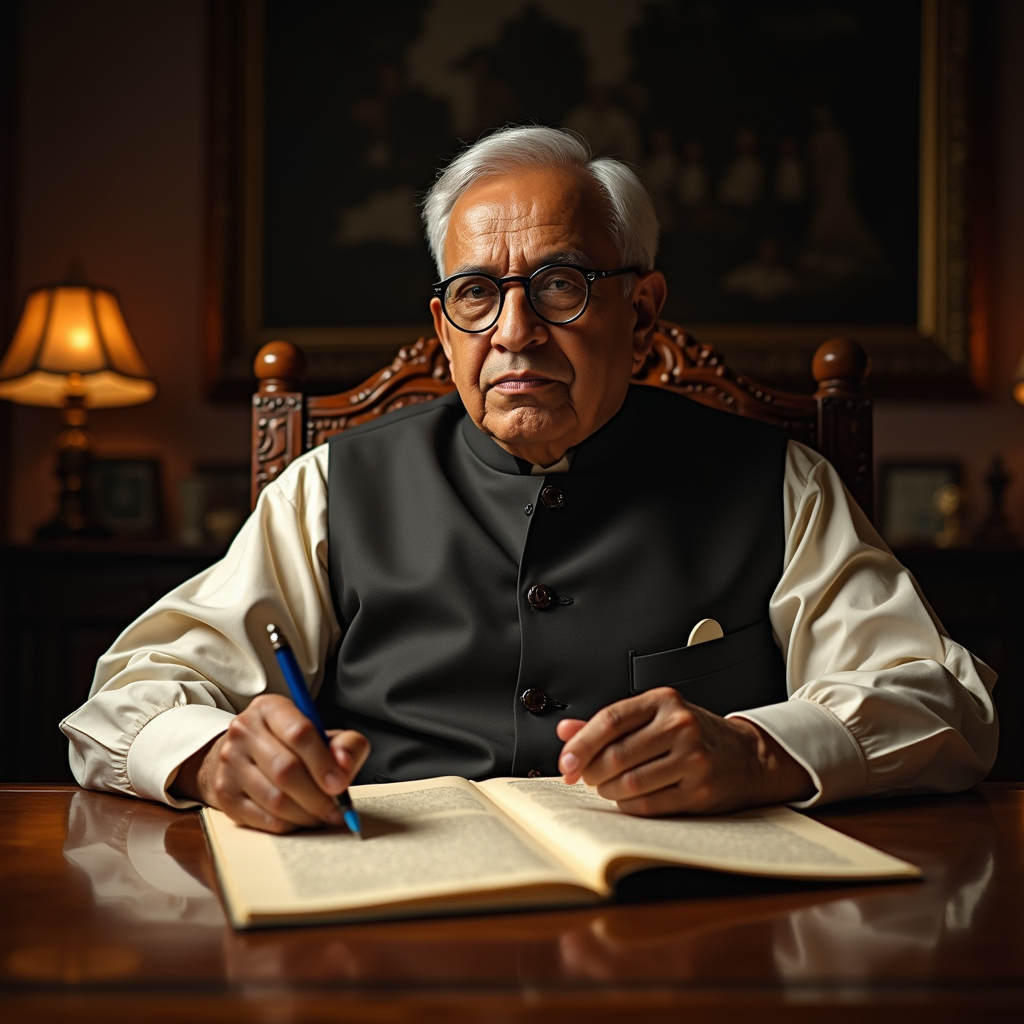

The framers of the Indian Constitution have curated the basis of the Indian legal system in a way where these rights are protected. Article 32 has been incorporated in the Constitution in order to protect the fundamental rights of an individual. According to Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, it is “the very soul of the Constitution and the very heart of it.” The fundamental rights enshrined under the Indian Constitution are incorporated to preserve an individual and his civil liberties from the atrocious legislative or executive actions. The courts have a right to declare an action which infringes any right of an individual as void under Article 13 of the Indian Constitution.

Right to constitutional remedies as the pillar of fundamental rights under the Indian Constitution

The Indian Constitution is acknowledged as the grundnorm of our nation, which enshrines fundamental rights under its provisions, serving as the supreme legal authority of the Indian legal system. By constitutional remedy, we mean the remedies that the Indian Constitution offers at instances where fundamental rights of an individual are infringed. The rights conferred under Part III leaves a shiny mark on the provisions of the Indian Constitution conspicuously, making it one of the vital segments of the Indian Constitution.

The Constitution enlists a comprehensive elaboration of fundamental rights under Part III, which categorises such rights broadly into six categories. To safeguard an individual from the infringement of any of these rights, constitutional remedies come into existence. While the article discusses constitutional remedies, it is important to explore six broadly classified fundamental rights. These are-

- Right to equality. (Articles 14-18)

- Right to freedom. (Articles 19-22)

- Right against exploitation. (Articles 23-24)

- Right to freedom of religion. (Articles 25-28)

- Cultural and educational rights, and right to constitutional remedies. (Articles 29-30)

The Indian Constitution enlists the fundamental rights under its Part III, from Article 12 to Article 35.

Article 13 of Constitution

The Indian Constitution provides that laws that are violative of the principles laid down in the Indian Constitution, which are prior to its commencement, shall be wholly void in its existence. Article 13(2) further abstains from enacting any legislative statute that violates the Constitution by abridging the rights conferred under Part III of the Indian Constitution. Any law that seems to be infringing fundamental rights shall be void to the extent of such infringement.

Article 14 of Constitution

Article 14 of the Indian Constitution is one of the foremost Articles that specifies regarding civil liberties of an individual and also states that no person shall be denied equality before law and equal protection of law within the territory of India. This provision of the Constitution is applied to any individual, irrespective of being a citizen, and further extends to any individual in existence within the geographical area of the nation.

Article 15 of Constitution

Article 15 of the Indian Constitution prohibits discrimination against an individual on the basis of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. This Article, under its clauses 2 (a) & (b), further provides that no citizen, irrespective of their religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth, shall be denied access to shops, public restaurants, hotels, and places of public entertainment or the utilisation of wells, tanks, bathing ghats, roads, and other public places that are managed wholly or partially by the State.

Article 16 of Constitution

Article 16 of the Indian Constitution secures equal opportunity for all citizens in the matter of employment under the State. The Article prohibits discrimination against an individual only on the basis of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, or residence of such an individual. To further elaborate, Article 16 has authorised the state authority to preserve and create special provisions for people who belong from the backward classes, those who are not adequately represented enough.

Articles 17 and 18 of Constitution

Where Article 17 of the Indian Constitution abolishes untouchability and also condemns any act which promotes untouchability, considering it to be an act of criminal offence. Furthermore, Article 18 of the Constitution prohibits the bestowal of titles to any individual.

Article 19 of Constitution

Article 19 of the Indian Constitution prescribes for the freedom of a citizen to express his beliefs, faith and opinion, i.e., the freedom of expression. This Article articulates many fundamental rights, following are those:

- The right to freely and peaceably assemble and without arms;

- The right to form associations;

- The right to move freely without any restriction within the territory of India;

- The right to reside and settle in any part within the Indian territorial jurisdiction;

- The right to own, hold or dispose of property; and

- The right to freely practise any profession of choice or to carry on business or trade. The Article in its content further provides that these rights contain certain restrictions and pertain to reasonable restraints.

Article 20 of Constitution

Article 20 of the Indian Constitution bestows an individual with the protection against conviction of offences. It provides that no individual shall be convicted for any offence except for his actions that constitute a violation of law. Provided that such law should be in force at the time of the commission of the alleged act. It further provides that no individual should be prosecuted and further convicted for the same offence, more than once. Furthermore, Article 20(3) also provides that no individual must be compelled to testify against himself, i.e., the right against self-incrimination.

Article 21 of Constitution

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution provides the freedom to life and personal liberty. The ambit of this Article is enlarged further by various judicial interpretations and the legal precedents set by them. This step has paved a path towards enlightenment against arbitrary actions, and activities that deprive a person of his life and personal liberty.

Article 22 of Constitution

Article 22 of the Indian Constitution protects an individual against arrest and detention. It states that an arrested person must be promptly informed about the grounds on which he is arrested. It further states that he must not be deprived of the right to be defended by a legal practitioner of his choice and fairly heard by the court. Furthermore, this Article compels an arrested person to be presented before the Magistrate within twenty-four hours of their arrest.

Article 23 and 24 of Constitution

Articles 23 and 24 address the right against exploitation. Article 23 specifically deals with exploitation of humans in trafficking and forced labour. On the other hand, Article 24 forbids child labour for the purpose of working in factories, especially the children below the age of fourteen years.

Article 25 to 28 of Constitution

The Indian Constitution, through Articles 25-28, prescribes for the freedom to religion. These Articles ensure the rights of an individual to profess, practice and propagate their choice of religion, as regards certain reasonable restrictions. These restrictions are subject to public order, morality and health, as well as to the other provisions of this part.

Furthermore, Article 26 provides for the establishment of religious denominations and further provides them with the powers to maintain institutions for charitable and religious purposes. The Article also allows the religious institutions to govern their own administration and manage their own affairs and to acquire property of their own, where such property may be movable or immovable. This Article further directs that the administration of such property must be in accordance with law.

Article 27 provides for an exemption from the payment of taxes concerning the promotion of any particular religion or religious denomination. Lastly, Article 28 prohibits the provision of any particular religion in educational institutions that are fully funded by the state, which ensures neutrality in matters of religion.

Article 29 of Constitution

Article 29 of the Indian Constitution protects the right to preserve and promote the unique culture of citizens who reside within the territory of India, having a distinct culture, language, or script of their own. This Article further prohibits any kind of discrimination on the basis of religion, race, caste, language, or any of them against citizens in the matters of admission to any educational institution, which are managed by the State.

Article 30 of Constitution

Article 30 of the Indian Constitution provides for the rights of minorities. This Article is comprehensive about minorities, expanding it on the basis of both religion and language. This Article empowers the minorities to establish, and administer educational institutions of their own. It also ensures that no educational institution shall be discriminated against by the State while granting aid, solely on the ground that the management of such institutions is by a religious or linguistic minority.

A pronouncement of fundamental rights is ineffective without the proper recourse for their enforcement. The existence of a remedy ensures the presence of effective enforcement of a right and the transformation of it into tangible reality. A right is nothing without a remedy. While reflecting on this, the constitutional framers established an effective mechanism for the enforcement of the rights under Article 32 of the Indian Constitution, which is a fundamental right in itself.

Remedies for enforcement of rights under Article 32

Heart and soul of the Constitution

Article 32 traces its origin during the reign of the Indian freedom struggle, where protection and preservation of the citizen’s rights became one of the prime priorities. During the time of pre-independence, there was an alarming need for a foundational legal framework in the Indian legal context that would serve the purpose of safeguarding the rights and personal liberties of an individual, against arbitrariness and abuse of power. This belief invited a revolutionary development that led to the protection of an individual from the infringement of fundamental rights.

This Article does not only serve as a theoretical hypothesis but also assures the enforcement of fundamental rights articulated under Part III. As Dr. B. R. Ambedkar once said, “If I was asked to name any particular Article in this Constitution as the most important – an Article without which this Constitution would be a nullity, I could not refer to any other Article except this one (Article 32). It is the very soul of the Constitution and the very heart of it.”

Unfettered power of the Supreme Court

Article 32 entitles the Supreme Court to possess a dimensional range of authority to uphold an individual’s personal liberty and their fundamental rights. The Supreme Court is empowered to issue writs, directives, or orders as prescribed under the Indian Constitution, under its Article 32 (2). The diversification of writs (discussed in detail later) has been made under this clause of Article 32, providing its various kinds, which are habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto and certiorari. Through this extensive power, the Supreme Court has played a pivotal role in shaping the understanding of the fundamental rights guaranteed under Part III of the Constitution.

Article 32 is a right that reinforces other rights. This is legally formulated under Article 32(1) of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees an individual the right to move to the Supreme Court through proper proceedings in order to restore their fundamental right.

Furthermore, Article 32(4) provides that the rights that are guaranteed to be protected and preserved, i.e., the fundamental rights, cannot be suspended, unless explicitly prescribed for by the Constitution. However, the rights enshrined under Part III of the Indian Constitution may be suspended during the proclamation of a national emergency.

By virtue of Article 358, Article 19 is bound to remain suspended till the proclamation of such an emergency continues. Furthermore, according to the 44th Constitutional Amendment Act, 1978, the rights enlisted under Article 19 may be suspended if a national emergency is declared due to war or external aggression rather than armed rebellion. Additionally, fundamental rights except Article 19 may be curtailed during national emergencies as provided under Article 359. However, the President is not given the authority to suspend Articles 20 and 21 of the Constitution, by virtue of Article 359.

Who can avail these rights

The right to constitutional remedies ensure that every individual can enforce their respective fundamental right. Both citizens and non-citizens can approach the courts to address the infringement of their fundamental right. Fundamental rights enshrined under Part III of the Indian Constitution provides remedies for both citizens and non-citizens.

Rights like right to protection against discrimination, freedom of religion, right to employment are restricted to the citizens of India, rights like equality before law, and protection of life and personal liberty apply to any individual, irrespective of their status of citizenship are included. Therefore, the implication is that if the right to life and personal liberty of a foreign tourist is infringed, such individuals can claim the restoration of their rights from the court.

The inclusivity of the genesis of fundamental rights among both citizens and non-citizens prove that these rights can be availed easily by any individual, provided certain exceptions, which may rule out the non-citizens from the same.

Let us now dive into the oceanic depth of the various case laws, which are discussed below.

Relevant case laws

Skill Lotto Solutions Pvt. Ltd. vs. Union of India (2020)

The Supreme Court in the case of Skill Lotto Solutions Pvt. Ltd. vs. Union of India (2020) held that Article 32 grants the right to approach the Supreme Court in order to enforce the rights mentioned under Part III of the Indian Constitution. It further held that this particular provision of the Constitution is one of the integral elements of the basic structure. The court emphasised the importance of this Article, observing that it is necessary to ensure the application of the rule of law.

Rashid Ahmed vs. The Municipal Board, Kairana. The Union of India and The Stat (1950)

The case, Rashid Ahmed vs. The Municipal Board, Kairana. The Union of India and The Stat (1950), was related to the infringement of the right to carry on one’s own business, which was supposedly halted by the Municipal Board of Kairana. The Municipal Board acted arbitrarily and rejected the clearance of the licence applied by the petitioner, on the basis of absurd reasons. Subsequently, the petitioner faced trial for allegedly violating the bylaws. The court, upholding the significance of Article 32, held that it is not limited to the issuance of prerogative writs but also extends to the power of directing or ordering in order to satisfy the purpose of restoring the fundamental right.

Mohammad Moin Faridullah Qureshi vs. The State of Maharashtra (2020)

The petitioner in the case of Mohammad Moin Faridullah Qureshi vs. The State of Maharashtra (2020) approached the Supreme Court in order to invoke Article 32 to challenge an impugned sentence imposed on him under the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987 (TADA). The petitioner contended that he must be given the benefit of being a juvenile, which was previously highlighted in the case.

The Supreme Court dismissed the petition and held that, even though Article 32 of the Indian Constitution is a strong tool for protecting fundamental rights, it has not been empowered to act as a general remedy with regard to an individual, especially for challenging any legal decisions. It further observed that in situations where the sentence imposed by the court is final, and its criminal appeal has been prosecuted and upheld by the Supreme Court, the utilisation of Article 32 cannot be made in order to reverse the sentence.

Article 226 of the Indian Constitution

Article 226, which is incorporated in Part V of the Constitution, empowers the High Courts to issue writs, orders or directives, broadly classified into following five classifications:

- Habeas corpus,

- Mandamus,

- Prohibition,

- Quo warranto, and

- Certiorari,

directing any person, an authority or the government. The remedy which is provided under this Article extends beyond the borderline of only fundamental rights and includes other legal purposes, which involve administrative abuse as well. While the nature that is central to Article 32 is a fundamental right, Article 226 is a constitutional right.

High Court’s power of superintendence

Article 227 of the Indian Constitution refers to the superintendent power of the High Courts to look over all the work done by the subordinate courts. This provision ensures the crucial maintenance of the rule of law and administration of justice in an effective way. The High Courts, using their superintendent power can supervise the workings of the subordinate courts and keep a check on whether proper administration of justice is followed. A High Court is empowered to intervene in matters where the fundamental rights of an individual are infringed.

According to Article 227(2) of the Indian Constitution, the High Courts may, without disturbing the generality of any legal procedure or formula, is empowered to do the following things:

- Article 227(2)(a) states that the High Courts may call for records of various pending judicial proceedings, the number of cases disposed of, or any information that may be relevant to address the issues concerning the proper administration of justice.

- Article 227(2)(b) of the Indian Constitution states that the High Courts are empowered to formulate rules and regulations and enforce them in order to govern the procedures and operations of the subordinate court.

- Article 227(2)(c) of the Indian Constitution prescribes that the High Courts have the authority to regulate the keeping of the court records, important administrative documents, financial accounts, etc.

These supervisory powers complement the constitutional remedies available for individuals in case of infringement of their rights. By conferring such rights upon the High Court, efficiency in the subordinate courts is ensured, while keeping a follow-up on the proper administration of justice.

Difference between powers of Supreme Court and High Court

| Basis | Supreme Court | High Court |

Scope of jurisdiction | The scope of jurisdiction of the Apex Court extends broader than any of the High Courts. It consists of the original jurisdiction, appellate jurisdiction, and advisory jurisdiction. | High courts of a particular state possess their restricted original jurisdiction, i.e., writs. They basically entertain appellate jurisdiction of the cases from the subordinate courts of their subordinate states. |

Original jurisdiction | The Supreme Court’s exclusive original jurisdiction involves the Government of India and one or more States, or between the Government of India, along with one or more states on one side and one or more states on the other side. The Supreme Court also covers disputes solely between two States. | Every High Court in India holds its original jurisdiction to issue its directives or orders through writs; Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Prohibition, Quo Warranto, and Certiorari. The High Courts exercise this jurisdiction in order to address the fundamental rights and their infringement. |

Appellate jurisdiction | The Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction may be obtained through a certificate issued by the concerned High Court under Articles 132(1), 133(1), or 134 of the Indian Constitution.In civil matters – Appeals to the Supreme Court are permitted in civil matters from a High Court if it certifies that: a) that such a matters involve a substantial question of law of a general substantial, b) in its opinion, the matter requires proper scrutiny by the Apex Court and needs to be disposed of by it.In criminal matters – Appeals to the Supreme Court are permitted in criminal matters from a High Court if such High Court -a) reverses an acquittal and imposes a punishment of death, or life imprisonment or imprisonment for at least ten years, on the accused, and b) withdraws a case from one of its subordinate courts with its own discretion, in order to conduct its trial. However, the punishment imposed must be a sentence of death, life imprisonment or imprisonment for ten years or more. The Supreme Court also preserves with it an exclusive appellate jurisdiction on all courts and tribunals all over India. The Apex Court under Article 136 of the Indian Constitution, may, at its discretion grant special leave to appeal from any decree, judgement, or order issued by any court or tribunal within the territorial division of India. | The High Courts of India have their appellate jurisdiction exclusively to themselves. All the matters, whether civil or criminal, are brought to the tables of a High Court, in order to address them, factually and lawfully. In civil matters – According to Section 100 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, an appeal shall lie with the High Court in cases where there is an involvement of substantial question of law. A High Court is further empowered to determine any issue necessary to be disposed of, where such an issue has not been addressed by the lower court or the lower appellate court, if any. A High Court is also empowered to address such matters in cases where the issues were wrongly determined by the subordinate courts. In criminal matters – The appellate jurisdiction of High Courts includes reviewing, hearing appeals from conviction, acquittals, and other sentences passed by the subordinate courts. According to Section 415 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (Section 374 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973) an appeal may lie with the High Court in case of a conviction by the Sessions Court or the Additional Sessions Judge.Apart from its regular appellate power, a High Court also has the power to review certain interlocutory orders, such as bail or stay of a proceeding. |

Advisory jurisdiction | The Supreme Court of India is vested with an exclusive power of advisory jurisdiction, provided under Article 143 of the Indian Constitution. This provision enables the Apex Court to give opinion on legal and substantial questions placed by the President of India, on its advisory powers. The President seeks legal guidance by enabling this provision and however, such a suggestion by the court is not binding, it comes up with a useful fruition. | High Courts of India are not exclusively empowered with the advisory jurisdiction but are eligible to address issues which are concerning and need a solution. High Courts, however, are authorised to guide the government officials and other public officers into legal complications, if needed. |

Writ jurisdiction | The Supreme Court of India is empowered to issue writs, in order to preserve the fundamental rights of an individual and protect those from infringement. Article 32 of the Indian Constitution empowers the Supreme Court with the authority to enforce the fundamental rights.These writs are issued by the court when approached by an individual or a group of individuals, whose rights are infringed. These writs are; Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Prohibition, Quo Warranto, and Certiorari. | The High Courts of India are sanctioned with the power of issuing their directives or orders through writs, namely; Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Prohibition, Quo Warranto, and Certiorari. Article 226 of the Indian Constitution empowers the High Courts of India with the authority to enforce the fundamental rights. The issuance of writs by a High Court is done to reinstate fundamental rights when breached and other administrative or ordinary legal purposes. |

Power to punish for contempt of court | The Supreme Court of India is empowered with the authority to punish for the contempt of court, including a contempt which is directed to itself. This is reflected in Article 129 and Article 142 of the Indian Constitution. Apart from the Indian Constitution, the provision regarding contempt of court and its punishment is provided under Rules to Regulate Proceedings for Contempt of the Supreme Court, 1975, read with Article 145 of the Constitution. Apart from the rules mentioned under Rule-2, Part-I of the Rules to Regulate Proceedings for Contempt of the Supreme Court, the court may initiate proceedings:Suo motu (on its own),Upon receiving a petition made by the Attorney General, or Solicitor General.On receiving a petition made by a person. In case of criminal contempt, such a petition must be filed with the consent of the Attorney General or the Solicitor General in writing. | The High Courts of India are exclusively designated as “court of record”, which spontaneously empowers them to punish for the contempt of court. The High Courts are empowered with this authority through Article 215 of the Indian Constitution. This power keeps a check on the well-functioning of the court procedures and well-maintenance of the orders produced by it. It further ensures that the courts can take actions against any conduct which disorients their functioning and proper administration of justice. |

What are writs

Writs are orders or directives that are either issued by the Supreme Court or the High Courts. The etymology of the word ‘writ’ is derived from an English word ‘gewrit’, which denotes a matter that is written. Writs may also interchangeably be called ‘prerogative writs’. The word ‘prerogative’ infers a specific right or privilege. In the earlier times, under the jurisprudence of English law, ‘prerogative’ or ‘prerogative powers’ symbolised sovereignty, which was exclusively held by the Crown or the individuals authorised to further delegate such a power. Primarily, prerogative writs were prevalent in England, as they were issued while the royal decrees were passed by the King, under the King’s Bench in London.

The Indian legal system incorporated the concept of prerogative writs in a more practical way, with the judiciary acting as the prime contributor through its judicial precedents and interpretation. The emergence of writs in India can be dated back to the Regulating Act of 1773, which led to the establishment of the Supreme Court in Fort Williams, Calcutta. Later, the The Supreme Court was replaced by the High Courts established in the three Presidency towns of Bombay, Madras and Calcutta, which were also authorised to issue writs.

Issuance of writ of Mandamus was authorised to the Presidency High Courts within their distinct jurisdictions, which was legally provisioned under Section 45 of the Specific Relief Act, 1877. Whereas, the writ of Habeas Corpus was imbibed under Section 491 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898. The development of prerogative writs has been assimilated into the Indian Constitution in the post-colonial era, where efforts were taken in its incorporation and effective execution were made through judicial precedents.

What are the types of writs

Let us now discuss the classification of the very important tool i.e., Writs. Following is a detailed discussion of the five kinds of writs, prevalent case laws under them and other important points.

Writ of Habeas Corpus

The literal meaning of ‘Habeas Corpus’ is “you shall have the body,” which has been derived from the Latin language. This classification of writ confers a legal remedy in circumstances where an individual is arrested unlawfully, or is under detention without any formal legal or proper procedure. This writ allows an individual to be free from such an illegal detention and enjoy his right to live with dignity as an individual.

The court is supposed to scrutinise the legality of the detention on the basis of proper evidence procured by the authorities that acted upon such detention. Only on that basis shall the court entertain the writ of Habeas Corpus and decide whether such a detention is illegal or not, as claimed by the petitioner. The court is empowered to release an individual on immediate bail if it finds that such detention was unlawful and did not follow the proper course of procedure.

The writ of Habeas Corpus plays a significant role in safeguarding an individual against arbitrary arrest and fallacies in the criminal procedural law. It protects and prevents a person from arbitrary abuse of power by authorities against an individual by shielding his personal liberty and rights. It is, therefore, considered to be a potent tool provided by the Constitution in order to maintain a balance between the state authorities and the rights of an individual.

Article 22 of the Indian Constitution establishes the fundamental right to protection against arbitrary arrests and detention. This Article obstructs the authorities from unlawfully detaining an individual, in the absence of any grounds or reasonable clarification. The Article further provides that due process of law must be adhered to in order to make a lawful detention. The breach of this fundamental right invokes the writ of Habeas Corpus, which is one of the main organs of the enforcement machinery, i.e., Article 32 of the Indian Constitution.

Applicability

A writ petition for Habeas Corpus may be filed by the individual who is illegally detained or by a person who would act as a representative of such a person. They can be a relative or a close acquaintance. However, the person becoming a party on behalf of the detained individual must be relevant and not be an unrelated third party to the incident. Furthermore, a petition for Habeas Corpus may be filed only on the account of actual detention, and not on a mere apprehension of it.

The Section 97 of the Code of Criminal procedure, 1973, now provisioned under Section 100 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, prescribes similar provisions as that of the writ of Habeas Corpus. It is stated in this provision that if the District Magistrate, Sub-Divisional Magistrate, or Magistrate of the First Class has an apprehension of a person to have been unlawfully detained, they have the authority to issue a search warrant within their authorised jurisdiction. The police are empowered through the warrant issued under this provision, which authorises them to enquire regarding the alleged unlawful detention and make them present before the court. The legislation ensures the preservation of an individual’s personal liberty and protection against the arbitrariness of the authorities.

Relevant case laws on writ of Habeas Corpus

Additional District Magistrate, Jabalpur vs. Shivkant Shukla Etc. Etc (1976)

Facts

The case of Additional District Magistrate, Jabalpur vs. Shivkant Shukla Etc. Etc. (1976) emerged due to the controversial emergency, which was declared by the then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, in the year 1975. Post the elections of the Lok Sabha, the fairness and integrity of the election were challenged in the Allahabad High Court, which annulled the election, stating it to be based on electoral misconduct. The annulment of this election endangered the Prime Minister’s powerful position and threatened her seat and its security, therefore becoming a threat of being disqualified from the office for six years.

The Prime Minister, considering all the possible threats and instability of her position, declared a state emergency on the 26th of June, 1975. This emergency led to the suspension of the fundamental rights, specifically enshrined under Articles 14, 21 and 22, and their enforcement machinery, enshrined under Article 32.

Due to the suspension of fundamental rights, several leaders and activists of the opposition were detained under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act, 1971 (MISA). Such alleged illegal detention included eminent activists like A.B. Vajpayee, Jayaprakash Narayan, and Morarji Desai. The suspension of Article 32 denied them of their basic individual right, while other High Courts ordered in the favour of the detained persons.

Issues

Two main issues were raised, which were:

- Whether the writ petition under Article 226, was maintainable under this case. This issue is raised concerning the presidential order under Article 359(1), focussing on whether a writ petition of Habeas Corpus shall be valid challenging the detention under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act, 1971.

- One of the main issues in this case was the spectrum of judicial review under this matter. This issue was raised concerning the applicability of judicial review if the writ under Article 226 became maintainable.

Judgement

The Supreme Court in its judgement in this case held that individuals are not entitled to file a petition under Article 226 in the High Court for Habeas Corpus or any other writ, while a state emergency is in motion, under Article 359(1). It further contended that the judiciary lacks the authority for judicial review or examination of the validating of the detention under MISA while upholding the validity of Section 16A(9) of the MISA. Article 359 was further interpreted by the Court, and it was observed that the Article suspends the enforcement of fundamental rights and allows the suspension of any proceedings that relate to the enforcement of fundamental rights.

Sunil Batra vs. Delhi Administration (1980)

Facts

In the Sunil Batra vs. Delhi Administration (1980) case, the petitioner, Sunil Batra, a jail inmate, intimidated the Supreme Court through a letter regarding the harsh living conditions of prisoners and the mistreatment that they faced. The petitioner also complained regarding one of his inmates being tortured by the head warden and whose relatives were threatened by the warden in order to extort money. The Supreme Court, after taking this letter into consideration, treated it as a writ of Habeas Corpus and public interest litigation.

The petitioner’s friend suffered serious anal injuries and was allegedly brutally hurt by an act of insertion of a metal rod into his anal. It was further observed that he was compelled to satisfy the sexual needs of the warden and was sexually assaulted. It was further contended by the petitioner that the rest of the prison officials denied the allegations against the warden in exchange of money and justified the injuries, claiming them to be self-inflicted.

Issues

Following were the issues raised:

- Whether the prison inmates were entitled to the liberties and rights provided to as any other individual? The issue was put further into addressing the inhumane conditions within prisons.

- Another issue was whether fundamental rights were applicable on the detained individuals.

- Issues were also raised addressing Section 30 of the Prison Act 1894, which prescribes for the confiscation of a prisoner’s property and their solitary confinement, if punished with death sentences. It also deals with Section 56 of the Act, which provides provisions regarding penalties for jailers. These provisions were questioned on the basis of their alignment with Articles 14 and 21 of the Indian Constitution.

Judgement

It was held by the Supreme Court in this case that it had the authority to intervene and reinforce the fundamental rights of prisoners. The court further held that the authorities were not entitled to torture the inmates in any kind of way, simply on the ground that they were detained prisoners as individuals. The court held that they were equally entitled to the rights enshrined under the Indian Constitution.

It further directed the police department to maintain humane conditions within the prisons. Addressing the issues raised regarding Section 30(2) of the Prison Act, 1894 the court held that solitary confinement does not permit the jail authorities to inflict unnecessary punishment and torture. The court, upholding the fundamental rights to life and liberty, stated that Section 30(2) of the Prison Act, 1894 contravenes Article 21.

A.K. Gopalan vs. The State of Madras (1950)

Facts

In the case of A.K. Gopalan vs. The State of Madras (1950), the petitioner, A.K. Gopalan, was a communist leader who was detained due to delivering a public speech. This led to the court passing a detention order against him under the Maintenance of Public Order Act, 1949. The detention was also declared illegal by the Madras High Court. The petitioner filed a writ of Habeas Corpus, which was also rejected on the ground that no bail was secured. Furthermore, another writ petition of Habeas Corpus was filed against which a new detention order was passed.

The petitioner further appealed to the Supreme Court through a writ petition under Article 32(1). He challenged the detention, claiming it to be unlawful and arbitrary. The petitioner also contended that the fundamental rights outlined under Article 19 and Article 21 of the Indian Constitution were infringed.

Issues

The following issues were raised in this case:

- Whether the Preventive Detention Act, 1950, aligns to the constitutional provisions, including Articles 14, 19, 21 and 22.

- Whether the order that was issued under Section 3(1) of the Preventive Detention Act infringed the fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 14, 19 and 21.

- Are the provisions under the Preventive Detention Act, 1950, in correspondence with the fundamental rights enshrined under Article 22.

- Whether the expression ‘Procedure established by law’ of the Indian Constitution associates with the meaning of ‘Due process of law’ provided in the American Constitution.

Judgement

It was held by the Supreme Court in this case that the Prevention Detention Act is not in conflict with Article 19 of the Constitution. It was observed that Article 19(1) is not applicable to individuals whose freedom is lawfully restricted and, therefore, is unenforceable. Consequently, the Prevention Detention Act does not violate Articles 19 and 21 of the Indian Constitution.

However, the majority of the bench was held by Kania C.J., Justice Mukherjee, Justice Das, and Patanjali Sastri JJ., who formulated that Section 14 of the Preventive Detention Act is unconstitutional, reasoning that it violates Articles 22(5) and 19(5). Although the whole Act must not be declared void, the provision that is in violation can be severed from the whole Act. The court further upheld the constitutional validity of Sections 3, 7 and 11 of the Act, allowing the government to detain individuals.

Furthermore, it was held by the court that Article 21 is a substantive right and interpreted ‘personal liberty’ from the viewpoint of Article 19 as the freedom to move freely tangibly throughout the Indian territory and held that such a right does not extend to other freedoms in this matter. It further reiterated that this article includes freedom in physical form and is limited in its scope. The court rejected the bail petition filed by the petitioner and held that there is no statutory provision incorporated by the Parliament to set a minimum period of detention under Article 22(7)(b).

Smt. Nilabati Behera Alias Lalit Behera vs. State of Orissa And Ors. (1993)

Facts

The petitioner, Nilabati Behra, in the case of Smt. Nilabati Behera vs. State of Orissa And Ors. (1993), wrote a letter to the Supreme Court when she found her accused son, Suman Behera, dead on railway tracks. The petitioner’s son was detained by the police under the charge of theft the day before. It was claimed by the petitioner in her letter that her twenty-two year-old son succumbed to the injuries inflicted upon him by the police. The Supreme Court, however, interpreted the letter written to it as a writ petition under Article 32 and addressed the matter further.

Issues

Following issues were raised in this case:

- Whether the petitioner’s claim of custodial violence and death is valid and maintainable according to the evidence produced.

- Whether the state was liable to pay damages, and if so, under what legal principles. This issue was further raised, outlining the difference between public liability and the liability inflicted by private law under a tortious action.

- On account of the existence of the doctrine of sovereign immunity, are the constitutional courts authorised to award pecuniary compensation for the violation of fundamental rights?

Judgement

It was held by the Supreme Court in this case that the death of the petitioner’s son occurred while being in police custody and allowed compensation to the petitioner for her son’s death, caused in the police custody. The State of Orissa, who was the respondent in this case, was held liable and was further directed to pay the petitioner, Nilabati Mehra, a sum of Rs. 1,50,000.

The court further highlighted that the compensation that was granted by the court by virtue of Article 32, or compensation that is granted by a High Court under Article 226, is a branch of public law remedy, which is purely based on the principle of strict liability. The principle of strict liability is asserted for the violation of fundamental rights in this case. The court in this case also highlighted the difference between both types of remedies under private and public law.

Rudul Sah vs. State of Bihar And Another (1983)

Facts

In the case of Rudul Sah vs. State of Bihar And Another (1983), the petitioner, Rudul Sah, filed a writ of Habeas Corpus with the Supreme Court, where he prayed for his release on the ground of false imprisonment. He claimed that the imprisonment of fourteen years violated his fundamental rights. The petitioner, before filing a writ petition in the Supreme Court, was charged for his wife’s murder in the year 1953 and later got convicted. However, he was detained in jail till the year 1982, even after being acquitted by the Muzaffarpur Sessions Court in 1968.

The petitioner prayed for his release while contending that he had faced fourteen years of false imprisonment. He also appealed the court to provide him with other ancillary reliefs, like monetary reimbursements for his rehabilitation and recovery, the reimbursement for medical therapy, and pecuniary compensation for his illegal detention for the whole duration.

The court considered the demands of the petitioner regarding ancillary reliefs and issued a show cause notice to the state, which focused on these claims. While responding to the Supreme Court’s order, the jailor of Muzaffarpur Central Jail cited two reasons for keeping the petitioner detained, which were;

- Firstly, it was decided that despite the order of acquittal, an order was passed by the Additional Sessions Judge of Muzaffarpur for the petitioner to remain in detention until the State Government and the Inspector General of Prisons, Bihar, further directed.

- Secondly, it was claimed by the jailor that the petitioner was of unsound mind and was restrained from being released from custody before any further order was made.

Issues

Following issues were raised in this case:

- Whether the court was authorised in awarding monetary compensation for the violation of fundamental rights under Article 32 of the Indian Constitution.

- Whether Article 21 incorporates the right to compensation for the breach of the right to personal liberty.

Judgement

The Supreme Court in this case held the petitioner’s fourteen years of custodial detention to be illegal and unjustifiable, and his claim was true. Furthermore, the court observed that the petitioner has been deprived of liberty to live, and denying the petitioner’s writ further would cause more trauma than already suffered by him, and he accepted the writ filed under Article 32. The court further emphasised the importance of the discretionary power and the authority that Article 32 holds.

The court further emphasised the infringed rights and the compulsory compensation to be made by the one who has infringed so, even if such an entity is the state. It also stated that denying such a right would be contrary to public interest and the protection of civil rights and liberties.

The court also believed that the petitioner should not have been deprived of his fundamental rights even if he was of unsound mind and that the state’s action lacked any basis and proper reasoning as to the illegal detention of the petitioner. The court also recognised the ancillary rights demanded by the petitioner to be valid and granted the same.

Kasturilal Ralia Ram Jain vs. The State Of Uttar Pradesh (1964)

Facts

In the case of Kasturilal Ralia Ram Jain vs. The State of Uttar Pradesh (1964), who was a businessman, got arrested by the police while he was travelling with some of his valuables, which also included a significant amount of gold. The policemen, after blocking his way, seized those items and kept them in their custody. The petitioner defended himself by mentioning the valuables being assets for his company and was still kept in detention. The following day, Kasturi Lal was released on bail, but out of all his valuables, only his silver belongings were returned to him, while he was refused by the policemen for the return of gold when requested for.

Subsequently, a lawsuit was filed by Kasturi Lal claiming the return of gold or a compensation equivalent to its value. Upon presenting its defence, the state denied all the allegations and refused herewith to produce the gold valuables or compensate the petitioner. They further defended, contending that the gold was kept under the custody of the then Head Constable, Mr. Amir, who stored all the valuables in ‘Police Malkhana’, who then absconded and fled to Pakistan. The state also said that despite taking several actions against the head constable, Mr. Amir, he could not be traced and taken into custody.

The Trial Court of Uttar Pradesh held the State to be liable and ordered to pay a compensation of Rs. 11,000 to Kasturi Lal. The State was aggrieved by the decision of the Trial Court and further appealed to the Allahabad High Court, who rejected the Trial Court’s judgement and supported the respondent’s arguments. The Allahabad High Court opined in its judgement that there was insufficient evidence regarding the alleged negligence that was caused by the police. It further held that even on the assumption of negligence, seeking monetary compensation from the state was unjustified on the part of the petitioner. The case was then further elevated to the Apex Court, appealed by the petitioner.

Issues

Following issues were raised in this case:

- Whether the policemen were actually negligent in their actions and responsibilities towards the belongings of Kasturi Lal, specifically gold.

- Whether the State is liable to compensate the petitioner for the Head Constable’s, Mr. Amir’s negligence regarding the petitioner’s gold belongings.

Judgement

While declaring its judgement, the Supreme Court referred to a case named Oriental Steam Navigation Company vs. Secretary of State for India (1861) 5 Bom. H.C.R. App. I, p.1. This case concerns the vicarious liability (a liability where one person is held liable for the actions of another person) of public servants. In that case, the state was allowed sovereign immunity, and the claim against the state of being vicariously liable was denied while dismissing the petition. In the present case, the Supreme Court referred to the ratio decidendi of this case, and held that the state was not vicariously liable for the actions of the head Constable, Mr. Amir.

However, it was held by the Supreme Court that the police officers were indeed negligent in keeping the belongings of Kasturi Lal in their custody. The Supreme Court observed that the property was negligently kept in police custody and addressed this issue in the favour of the appellant.

While addressing the next issue, which was concerned with the sovereign immunity of the state, the court referred to the same case as mentioned above and followed the rationale behind its judgement. It held that the state was immuned by the sovereign powers that it possessed, and therefore, the claim against the state of Uttar Pradesh was denied.

The writ of Mandamus was issued by the court under this case, which was proved to be one of the significant constitutional remedies. The infringement of the right of Kasturilal Ralia Ram Jain was addressed through the writ of Habeas Corpus, where it was claimed that the statutory power was abused as he was illegally detained as well as his valuables.

Writ of Mandamus

The literal meaning of ‘mandamus’ is to ‘command’. This diversification of writ infers the issuance of an order or a directive to compel an individual, lower court or any other authority, or the government to fulfil their respective public duties and responsibilities that they are legally obliged to perform. Individuals who are affected by the breach of their fundamental rights have the authority to appeal to a High Court under Article 226 or the Supreme Court under Article 32 of the Indian Constitution for the issuance of a writ of Mandamus.

The Supreme Court or a High Court may issue a writ of Mandamus for the enforcement of fundamental rights and to restrain a public official or authority from taking actions that might adversely affect an individual and the rights conformed to him.

Additionally, a High Court is authorised to issue a writ of Mandamus addressing some specific purposes, and these purposes do not come under the purview of the Supreme Court. These include:

- Directives addressing issues other than the infringement of fundamental rights of an individual.

- A High Court has the jurisdiction to issue the writ of Mandamus, which addresses actions which are unconstitutional, compelling on the part of a public holding office.

- A High Court may direct a lower court of a tribunal to exercise its duty on its refusal, and address matters where a public official exceeds its jurisdiction in a malicious, unlawful manner and abuses their discretionary power.

Certain conditions need to be adhered to before the issuance of a writ of Mandamus.

- Firstly, the person or the authority against whom the writ is issued must have a public duty to perform, which they must have failed to discharge. Such a duty must be obligatory or mandatory in nature, rather than discretionary.

- Secondly, the person who is seeking the writ of Mandamus must have the right to compel the public official to perform his duty. It must be noted that the petitioner should have already requested the public official to discharge his duty before seeking from the court a writ of Mandamus against the official.

Types of Mandamus

The writ of Mandamus has been classified into the following categories based on their nature of issuance and execution.

Certiorarified Mandamus

This kind of writ is an amalgamation of the writ of Mandamus and the writ of Certiorari. In this kind of writ, a judicial review of a decision is made where such a decision has already been made by a subordinate court on an earlier instance. A writ of Certiorari is passed in matters concerning excessive jurisdiction while discharge of certain duty. In some circumstances, the writ of Mandamus and certiorari may collide, where a writ of Mandamus shall have the power to retry the case, which was rescinded by a writ of Certiorari priorly.

Peremptory Mandamus

The meaning of peremptory is something that is absolute, firm and not debatable, and something that can be said lies in its final decision. Similarly, a writ in the nature of a peremptory mandamus is a directive by the court to the governmental agencies or a public official to perform their respective duties without any failure.

This kind of writ differs from an alternative mandamus. In cases where the officials do not comply with the orders of the court and cannot satisfy the court as to why the writ must be denied, a peremptory writ of Mandamus shall be issued by the court. It may so happen in circumstances where emergencies arise that a peremptory writ may be issued directing the government officials to comply with it without issuing an alternative writ.

Continuing Mandamus

In certain circumstances, a mandatory follow-up is required after the issuance of Mandamus, which tends to be in the nature of the continuing process. This is done to ensure proper compliance. Furthermore, the court may require periodic compliance reports from the authority against whom the writ of Mandamus is issued. This kind of writ makes sure that the court’s orders are not merely issued but are diligently and actively enforced.

Relevant case laws on writ of Mandamus

S.P. Gupta vs. Union of India & Anr. (1982)

Facts

It was in the year 1981 that several petitions were filed by lawyers and legal practitioners across different High Courts of India. Under the case of S.P. Gupta vs. Union of India & Anr. (1982), the petitioners filed petitions regarding the non-appointment, and transfer of two judges. It was contended that the procedure followed for the appointment of judges was unconstitutional in the petition that was filed in the Delhi High Court.

The issue was raised, mainly due to the short-appointment of three additional judges in the Supreme Court, which was claimed to be non-justiciable under Article 224 of the Indian Constitution. Among these petitioners, S.P. Gupta was one of them, who was a practising attorney at the Allahabad High Court. He filed a petition with the Supreme Court against the appointment of three judges, namely Justice Murlidhar, Justice A.N. Verma, and Justice N.N. Mittal. The claims and contentions that were made in the petitions were defended by the respondent by contending that the government’s order and the appointment of judges were not unconstitutional and did not infringe anyone’s fundamental right.

Issues

Following issues were raised in this case:

- Whether the order passed by the Central Government for the non-appointment and transfer of judges was constitutionally valid.

- One of the issues was concerned with the communication between the Minister of Law, Chief Justice of Delhi High Court, and the Chief Justice of India.

- Whether the petitioners were entitled and authorised to bring this case to the court.

- One of the issues also emphasised the independence of the judiciary and procedure for the appointment of judges in higher forums.

Judgement

The formation of a collegium was recommended by Justice Bhagwati in this judgement for the purpose of recommending candidates to the President for judicial appointments in the Supreme Court and High Court. While interpreting the meaning of ‘consultation’, the judges interpreted that it implies a meaningful exchange, and a decision must be made after considering all the pertinent and significant facts.

Justice Venkataramaiah, in his judgement, opined that Article 217 of the Constitution has empowered the President of India to appoint the High Court judges. However, it is also mentioned that the President must consult certain authorities, but he shall not be bound to follow their suggestions.

The court observed that the judiciary would lose its importance if the executive had the authority to intervene in the procedure of appointment of Supreme Court and High Court judges. The court also observed that with the establishment of the collegium system, the independence of the judiciary can be preserved.

Suganmal vs. State of Madhya Pradesh And Ors. (1965)

Facts

In the case of Suganmal vs. State of Madhya Pradesh And Ors. (1965), the appellant was the managing proprietor of Bhandari Iron and Steel Company in Indore and paid industrial tax provisioned under the Indore Industrial Tax Act, 1927. The company was directed to pay tax even after not being involved in the business of cotton milling. The company, however, transacted two advance payments, which they were not liable to pay for, and appealed before the court while the final tax assessments were calculated in the years 1951–1952. The court allowed the appeal, and it was held that the company was not liable to pay the industrial tax, the order refused for the tax payment to be refunded. The appellant requested a refund from the Madhya Pradesh State Government and was partly paid in return.

The appellant filed a writ of Mandamus in the Madhya Pradesh High Court to issue a directive for the state government to refund the rest of the money to the company, which was rejected. Subsequently, the appellant further filed an appeal to the Supreme Court. The Madhya Pradesh High Court opined that the state was not obliged to refund the tax amount to the company and also observed that it was the appellate authority’s decision to order such an execution.

Issues

Following issues were raised in this case:

- Whether the writ of Mandamus filed under Article 226 of the Indian Constitution was maintainable in this case.

- Whether the state had a statutory obligation to refund the tax amount partly paid by the company.

- Whether the Madhya Pradesh High Court was true in law and fact to dismiss the appeal by the company and further rejecting the contentions of the refund payment of the tax amount.

Judgement

It was held by the Supreme Court that a High Court has the power to issue writs within the purview of Article 226 of the Constitution. However, a petition that is solely seeking a writ of Mandamus in order to compel the state to refund money is not maintainable. The court further held that the appellants can approach the High Court for scrutinising whether the tax assessment was in violation of the very Constitution. This stance was supported by the court by stating that the claim for refund is maintainable only through a civil suit and a writ of Mandamus cannot compel the state to refund the tax amount.

Sangita Vilas Ingle vs. State of Maharashtra & Ors. (2017)

Facts

In the case of Sangita Vilas Ingle vs. State of Maharashtra & Ors. (2017), the appellant in the first place suffered torture and illegal acts from the policemen and other authorities, against which she filed a writ petition of Mandamus in the Bombay High Court. The High Court rejected the contentions of the petitioner. It stated that there were other remedies that the petitioner had, and the alleged complaints are viable enough to be filed before a judicial magistrate rather than before a High Court through a writ petition. The case was later elevated to the Supreme Court for its further appeal.

Issues

Following issues were raised in this case:

- Whether the Bombay High Court was justified in its dismissal of the writ petition solely on the grounds of the disputed question of facts.

- Whether the Bombay High Court should have scrutinised all the underlying merits of the writ petition before the dismissal.

Judgement

An appeal was filed with the Supreme Court, where it was found that the Bombay High Court wronged the law for dismissing the appeal solely on the basis of disputed facts. The Supreme Court further held that the High Court must have analysed all the merits of the case, concerning the nature of the reliefs sought by the appellant. Subsequently, the appeal was allowed by the Supreme Court, and it further quashed the decision of the Bombay High Court. The court also issued a directive for an expeditious hearing and examined the merits, suggesting it be disposed of within one year.

State of West Bengal And Others vs. Nuruddin Mallik And Others (1998)

Facts

In the case of State of West Bengal And Others vs. Nuruddin Mallik And Others (1998), a madrasah in West Bengal, named Bishalaxmipur Pune Shah Mastania Junior High Madrasah, offered students primary education, specifically from classes V to VII. Later, this educational institution intended to expand and upgrade their courses, including higher education (a high madrasah), which would incorporate classes from V to X to classes IX-X. This expansion was done without any prior approval or sanction from the competent authorities. With time, the Madrasah expanded its administration, and their staff increased along with the enrolment of the students for classes IX-X. Despite having no prior approval regarding the expansion, the board allowed for the students to appear for the examinations.

Later, two writ petition of Mandamus were filed in the Calcutta High Court, praying to command the Madrasah authorities to recognise the Madrasah as a High Madrasah. The case was later elevated to the Apex Court for its decision.

Issues

Following issues were raised in this case:

- Whether it was obligatory on the part of the authorities to grant the approval for the expansion of to the teaching and non-teaching staff, which also included the Head Master, in their respective posts.

- Whether the Calcutta High Court was true in ordering the board to approve the services of all the staff and to release their salary within the stipulated period.

Judgement

The Supreme Court laid its focus on the importance of education and held that there must be proper adherence to the procedural guidelines during the recruitment of staff members and other administrative jobs. It further observed that the approval sought by the Madrasah for a number of teaching and non-teaching staff members exceeded the allowed staff pattern. It was further observed by the court that many proposed staff did not meet their requisite qualifications.

Additionally, the court, in its judgement, directed the authorities to sanction the approval of the teaching and non-teaching staff by scrutinising their respective qualifications and following the mandatory procedures. The court in its verdict ordered the authorities to make a decision within four months and to avoid unnecessary delay that might hamper the smooth functioning of the institution.

Writ of Prohibition

The literal meaning of ‘prohibition’ may be derived as ‘to forbid’ or ‘to prohibit’ or ‘to restrain’. In legal language, the writ of Prohibition may be referred to as a ‘stay order’. Prohibition is considered a legal remedy that is appealed from a higher court to prohibit a lower court, an administrative body or a tribunal from exceeding its jurisdiction while acting upon it.

According to the definition provided in Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a writ of Prohibition is “a writ issued by a superior court to prevent an inferior court from acting beyond its jurisdiction.” In other words, a writ of Prohibition is an order or directive issued by a higher court instructing a lower court to cease proceedings that exceed its legal authority or violate the principles of natural justice. The writ of Prohibition serves the purpose of protecting from errors and preventing potential harm from arbitrariness or biassed proceedings.

Grounds to issue the writ of Prohibition

Certain conditions must be fulfilled in order to issue a writ of prohibition, which are elaborated as follows:

Infringement of fundamental rights

If a right which is instituted upon an individual is infringed by one of the lower courts or tribunal, the writ of Prohibition may be issued by a higher court. Although it must be properly assessed if there has been an infringement of any fundamental rights, such as right to freedom of religion, right to freedom of expression, right to freedom of education, etc.

Unconstitutional or ultra vires acts

A writ of Prohibition may be issued by the higher forums on an instance when a lower court or tribunal operates in a manner that is unconstitutional or otherwise exceeds its jurisdiction. This kind of writ may be sought to prevent any further unlawful or constitutional acts by the lower forums or tribunals.

Evidence not properly procured

A writ of Prohibition may be issued by a court in cases where a judgement passed by a lower court or tribunal was without proper procurement of evidence or in disregard of the truth. This ground includes proving that the lower court’s decision is founded on a significant factual error or is derived out of a misrepresentation of evidence.

Relevant case law on writ of Prohibition

Sheshank Sea Foods Pvt. Ltd. vs. Union of India & Ors. (1996)

Facts

In the case of Sheshank Sea Foods Pvt. Ltd. vs. Union of India & Ors. (1996), M/s. Kamath Packaging Ltd. filed a writ petition of prohibition in the High Court of Karnataka, praying for the prohibition of search and seizure to be conducted by the customs authorities in their godown. The petitioners contended that the customs authorities were not accredited to examine or conduct an investigation regarding the raw materials, which were imported under advance licence granted under the Duty Exemption Scheme. The petitioners, in their petition, also contended that the Customs Act, 1962, did not empower the authorities to investigate these matters.

Issues

Following issues were raised in this case:

- Whether the customs authorities were authorised to investigate and conduct a seizure and search operation regarding the utilisation of raw materials.

- Whether the Customs Act, 1962, made the customs authorities entitled to enforce compliance with the notified terms and conditions, issued under Section 25(1) of the Customs Act.

- Whether the customs authorities were permitted to investigate regarding the matters related to sale or misuse of exempt materials as per the Export Policy, 1988-91, and Handbook of Procedures, where the Duty Exemption Scheme is enshrined.

- Whether Section 111(o) of the Customs Act, 1962, which provides for the confiscation of goods exempt from duty under certain conditions, authorised the Customs authorities to take actions for not adhering to the conditions specified in the Exemption Notification.

Judgement

In this case, the Karnataka High Court, both the single and division bench, upheld in its judgement the legal authority of the customs authorities to investigate and administer compliance while applying the conditions of the exemption under which the raw materials were imported. The court further held that it was the customs authorities who were authorised to examine the utilisation of imported raw materials, despite the advance licences, including the conditions of the exemption notification.

The court further held that the Import and Export Policy and the Handbook of Procedures did not curtail the Customs authorities’ control to investigate alleged violations of exemption conditions.

Writ of Quo Warranto

The literal meaning of the Latin phrase ‘Quo Warranto’ is ‘By what authority or warranto’. This classification of writ pertains to a directive or an order that questions the authority of an individual or the right to hold a public office, position or franchise. The writ of Quo Warranto is employed to challenge the authority or a right of an individual to hold a specific position that is pertained to powers and rights.

In the ancient age, the Crown utilised the writ of Quo Warranto as a mechanism in order to assert control over public offices and prevent unauthorised individuals from holding them. With the timeline, the writ of Quo Warranto has evolved with its main purpose to safeguard the citizen’s rights and ensure that the public offices are rightly authorised.

Grounds for seeking the writ of Quo Warranto

Certain conditions must be followed by a higher court in order to issue an order or a directive under the writ of Quo Warranto. Following is an elaboration of the same:

Abuse of power

A court may issue a writ of Quo Warranto against an individual who is deemed to be abusing the authority he is empowered with. The court has the right to question their authority to hold the office after examining the circumstances and cases of that matter.

Disqualification of an authorised individual

A writ of Quo Warranto may be sought to be obtained if it has been found that the officeholder has been convicted of committing a criminal offence. The court may question the legality of the individual regarding holding the office.

Dual capacity of office

A writ of Quo Warranto may also be issued against an individual who is an officeholder and is holding more than one office simultaneously. The court may conduct a proper investigation, examine the evidence and follow the proper procedure before the issuance of a writ.

Relevant case law on writ of Quo Warranto

The University of Mysore and Anr. vs. C. D. Govinda Rao and Anr. (1963)

Facts

In the case of The University of Mysore and Anr. vs. C. D. Govinda Rao and Anr. (1963), the petitioner, C. D. Govinda Rao, filed a petition in the Mysore High Court under Article 226 praying for the issuance of a writ of Quo Warranto. The petitioner questioned the position of Anniah Gowda as research reader in English of Central College, Bangalore.

The petitioner provided a list of certain conditions that were required for the appointment as a research reader, which included a first or high second-class master degree from an Indian university or a foreign university, equivalent; a research degree at doctorate level; ten years (minimum 5 years) of experience in teaching the postgraduate classes; knowledge of the regional language, Kannada, was also preferred. The petitioner also argued that the existing Research Reader, Anniah Gowda, did not have most of these qualifications and, therefore, had no authority in holding the post. The case was then elevated to the Supreme Court.

Issues

Following issues were raised in this case:

- The validity of the appointment of Anniah Gowda as the post of Research Reader.

- Whether the petitioner himself had all the qualifications for the post of Research Reader of English at the College.

- Whether the writ of Quo Warranto was maintainable in order to demonstrate the authority under which the research reader was holding his position.

- The maintainability of the writ of Mandamus directing the University of Mysore to appoint the petitioner as the Research Reader.

Judgement

The Karnataka High Court found that the appointment of Anniah Gowda as a research reader in English at Central College was not in compliance with all the qualifications and material requirements. The court further criticised the conduct of the college, notably regarding the discrepancies and inaccuracies in the service records, further quashing the appointment of Anniah Gowda, declaring it not legal.

The case was further appealed in the Apex Court by the aggrieved party, i.e., Anniah Gowda, where the court set aside the order given by the Karnataka High Court and held the appointment of Anniah Gowda to be valid and very much in law. The Supreme Court further observed that although the High Court’s remarks regarding the initial affidavit were justified due to certain discrepancies, it was too harsh on the legality of the appellant’s appointment. It further reinforced that the Karnataka High Court should have considered the relevant facts, including the appellant’s detailed affidavit, which listed all his qualifications, in alignment with the requirements.

Writ of Certiorari

The literal meaning of certiorari is ‘to be certified’ or ‘to be informed’, whose meaning is derived from a Latin term. This is one of the categories of writs that are issued by a higher authority in order to certify the nullity of a previous decision rendered by a lower court or subordinate courts, tribunals or public authorities.

The definition of certiorari may be derived as “a writ of superior court to call up the records of an inferior court or a body acting in a quasi-judicial capacity.” Furthermore, it can also be issued against statutory bodies, whether exercising their judicial or quasi-judicial capacity. The prime focus of this writ is to assess whether the lower court or the administrative authorities have rightly applied the law while its interpretation. The concept of the writ of Certiorari emerges from the Common Law of England, while its origin is traced back to Medical England.

Prior to independence, the Government Act of India, 1935, provided for broader powers to the Federal Court and High Courts, empowering them to issue directives through writ of Certiorari to uphold the fundamental rights of an individual.

Reasons for seeking a writ of Certiorari

Certain conditions that need to be adhered to by a higher court in order to issue an order or a directive under the writ of Certiorari are as follows:

Jurisdictional error

A writ of Certiorari may be issued by a court on instances when the lower courts exceed its authority or at the failure of the exercise of such authority.

Error of law

If it is observed by any party to a case that there has been an error in law by a court, such party may pray from a higher forum to issue the writ of Certiorari. Such errors might lead to an unjust or significantly wrong decision, affecting equity, justice and the very fundamental purpose of them, and therefore, an issuance of a writ of Certiorari is a way out.

Substantial question of law

A case must have a substantial question of law in order to be addressed before a High Court or the Supreme Court. A higher forum or a court cannot, apart from an exceptional case, procure new evidence and scrutinise the facts and circumstances. A court is only authorised to analyse the evidence of a case if there is a substantial question of law attached to it. Such a substantial question of law includes interpretation of any statutory or constitutional provision or something of such importance that weighs equally to justice and equity.

Disputed decisions

A certiorari may be issued by a higher forum in cases where there is a conflict in decisions among the High Courts. Such a directive by the higher forum shall be empowered to analyse the case, contentions and arguments proposed by both parties, and the conclusion drawn by the courts. On such an analysis, a court may produce its verdict quashing dilemmas among the High Courts.

Violation of natural justice

On an instance of the infringement of natural justice, a writ of Mandamus can be issued to restore the principles of natural justice. These infringements may be caused by factors like coercion, fraud, or collusion.

Judicial review

A writ of Certiorari may be issued in order to execute judicial review. This classification of writ allows the ambit of judicial review by the Indian judicial system to expand.

Relevant case law on writ of Certiorari

K.V.S.Ram vs. Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corp. (2015)

Facts

In the case of K.V.S. Ram vs. Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corp. (2015), the appellant was accused of having obtained his position through a fraudulent transfer certificate. The appellant worked as a driver for the Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corporation. An inquiry was initiated regarding the accusations against the appellant to investigate whether the appointment of the appellant was obtained through a fraudulent transfer certificate.

Issues

Following issues were raised in this case:

- Whether the dismissal of the appellant from his position as driver at the Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corporation was justified. This issue involves reviewing whether the disciplinary authority acted within its jurisdiction and followed due process in imposing the punishment.

- Whether the punishment of dismissal was corresponding to the alleged misconduct of the appellant.

- Whether the verdicts given by the High Court of Karnataka, both by the Single Judge and the Division Bench, were justified and true in law.

Judgement

The case was further appealed to the Apex Court for its judicial review, where the Supreme Court observed that the High Court division bench’s decision to affirm the dismissal was incorrect. It further observed that the excessive delay in the inquiry, the appellant’s age, and the fact that similarly situated employees had been given lesser penalties all were in alignment with the Labour Court’s choice to reinstate the appellant with a reduced sanction.

In furtherance to it, the Supreme Court also found that the Labour Court had properly exercised its discretion under Section 11A of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 which provisions for the powers of Labour Courts, Tribunals and National Tribunals to give appropriate relief in case of discharge or dismissal of workmen. Therefore, it overturned the High Court’s judgement, reinstating the Labour Court’s award and ordering the appellant’s reinstatement.

An overview of the writs

| Writ | Description | Issuance authority | Against whom it can be issued | Against whom it cannot be issued |