This article is written by Yash Jain, a third-year student of Institute of Law, Nirma University. The article explores the status of “minority classes” from the ancient period to the current era. The article further provides a detailed account of constitutional provisions and cases for the protection of interest of minorities in the country.

Minority rights have gained greater visibility and relevance all over the world. India being a multi-ethnic, multi-religious, multi-linguistic and multi-cultural society is also not an exception to it. India does not promote or encourage any particular religion and ethnicity. Brotherhood is the essence of its soul and hence India is called a secular country. Diversity is the heart of India and it is in this context that minority rights have added significance to the post-independence era.

During the making of the Constitution, it was upon the constitutional framers that whatever wrong has been done to the people in the past should be rectified through the provisions of the new Constitution. The Constitution should provide safeguards for the minorities and special provisions for the upliftment of the minorities. The preservation of discrimination seeks to secure that everyone as individuals are treated on an equal basis and this is what the Constitutional framers aimed at.

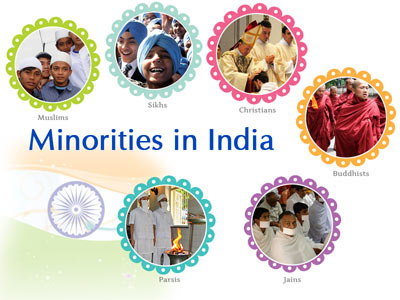

The Constitution has given recognition to a number of languages in the Eighth Schedule and there existed five religious groups which have been given the statutory status of National Minorities to the communities namely, Muslims, Sikhs, Buddhists, Parsees and Jains. Today, minority rights have introduced two new magnitudes into democracy. First, they have made the community a legitimate subject of political dialogue and second, they have placed the issue of inter-group equality on the agenda.

The Constitution has to provide and promote safeguards so that the inter-group equality in the multi-ethnic society of India should come to an equal footing. The framers of the Constitution bestowed considerable thought and attention upon the minority problems in all its facets and provided constitutional and statutory safeguards. Yet the issue has invaded questions till today. The constitution framers took all steps and the provisions have been laid down in the Constitution of India still there are certain questions which have created a struggle between the majority and minority which still exists and even needs an answer.

Some fundamental questions that need to be pondered upon are:

- What status has the polity granted to its minorities?

- What are the problems faced by the minorities especially in the context of inclusion and exclusion in stake building in post-colonial India?

- What are the provisions granted to minorities?

- If there are provisions made for the minorities whether they have been implemented properly?

- What is the role of minorities in politics, socio-economic development?

- What is the extent of prejudice and discrimination faced by them even today?

In order to answer and compensate the minorities for the wrongs done to them in the past, compensate the members of the discriminated group that are placed at a disadvantaged position Article 15(1) of the Constitution specifically debars the State from discriminating against any citizen of India on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them.

Article 15 of the Constitution provides that “The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them.” This means a very strict and stringent provision has been laid down in the Constitution of India to safeguard and protect the minority rights.

Defining Minority

Minority includes only those groups in the population which possess and wish to preserve ethnic, religious or linguistic traditions or characteristics different from those of the rest of the population.

Sociologist Louis Wirth defined a minority as “a group of people who, because of their physical or cultural characteristics, are singled out from the others in the society in which they live for differential and unequal treatment, and who therefore regard themselves as objects of collective discrimination.”

According to Francesco Capotorti, UN Special Rapporteur in his report laid down what constitutes a minority:

“A group numerically inferior to the rest of the population of a State, in a non-dominant position, whose members being nationals of the State possess ethnic, religious or linguistic characteristics differing from those of the rest of the population and show, if only implicitly, a sense of solidarity, directed towards preserving their culture, traditions, religion or language.”

Conceptualization of Schedule Caste and Backward Classes

The earliest reference to the caste system is found in the Rig Veda in which it is mentioned that there exist four castes which originated from Brahma, the supreme being. It was believed that the Brahmans came from the mouth, Kshatriyas from the arms, Vaishyas from the thighs and Shudras from his feet. Brahmans were considered as the instructors of mankind, Kshatriyas were the warrior class, Vaishyas and Shudras were treated as the agriculturists and servants respectively.

From the time of Rig Veda, Shudras which in the present circumstances are called Schedule Class and Backward Classes, were not treated equally and were treated with inhumanity. The term “Schedule Class” was adopted for the first time in the year 1985, when the lowest ranking Hindu castes were enlisted in the schedule annexed to the Government of India Act for the purpose of statutory safeguards and other benefits that are provided to them.

The Britishers played a dominant role in the awakening of India towards the plight of Schedule Castes. They ushered the principle of complete equality and justice irrespective of race, colour, caste, creed, religion, etc. and the same has been incorporated in Article 15(1) of the Constitution by the constitutional framers. Subsequently, after the independence of India with the coming of the Constitution, efforts were made to uplift the status of minorities in the country.

The Constituent Assembly was very concerned about the issue of protection of minorities and other weaker sections of the country. The committee deliberated various matters related to security, preservation and position of women in the society into two sub-committees i.e. the fundamental right sub-committee and the minority sub-committee. Among the two, the minority sub-committee was primarily formed to look after the matters of minorities.

Criteria for Identifying Backward Classes

The Central and State Governments can identify the Backward Classes based on the criteria recommended by Commission or Committee constituted under Article 340 of the Constitution of India.

Article 340 of the Constitution – Appointment of a Commission to investigate the conditions of backward classes

The President may, by order appoint a Commission consisting of such persons as he thinks fit to investigate the conditions of socially and educationally backward classes within the territory of India and the difficulties under which they labour and to make recommendations as to the steps that should be taken by the Union or any State to remove such difficulties and to improve their condition and as to the grants that should be made for the purpose by the Union or any State the conditions subject to which such grants should be made, and the order appointing such Commission shall define the procedure to be followed by the Commission.

The Kalelkar Commission (1955) and the Mandal Commission (1980) were accordingly constituted to look after the conditions of the Backward Classes in the country. No fixed criteria for identification of “Other Backward Classes” was provided by the Kalelkar Commission. Whereas, the Mandal Commission held that “socially and educationally backwards” are not necessarily “economically backward classes”. The Commission found that class backwardness was a phenomenon of low caste, hence, the criteria for deciding backwardness of a class has been fixed as follows:

- Low social position in the traditional caste hierarchy of the Hindu Society.

- Lack of general education opportunities for the major section of a backward class or community.

- Inadequate or no opportunities in the matters of public service.

- Inadequate representation in trade, commerce and industry.

Specific provisions are laid down in the Indian Constitution for protection of Schedule Caste and Backward Classes. Recognising the special needs for Scheduled Caste and Backward Classes, the Constitution of India not only guarantees them equality before the law under Article 14 but also enjoys the state to make special provisions in favour of Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribes and Backward Classes for their upliftment in the society under Article 15(4). It also empowers the State to make provisions for reservations in appointments and promotions in favour of any backward classes under Article 16(4). In the Constitution, the provisions guaranteeing the protection of Schedule Caste and Backward Classes can be studied under 3 heads i.e.

- Protection of Social Interest

- Protection of Economic Interest

- Protection of Political Interest

Protection of Social Interest

The protection of the social interest of the minorities is laid down under Article 14 which talks about equality before the law. It means that no one should be discriminated on the basis of caste, colour, sex, creed etc. further, Article 15(4) talks about the protection of social interest by laying down that special provisions for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes including SCs and STs should be made. Article 16 protects the interest of minorities by granting abolition of untouchability and its protection in any form. Article 30 administers All minorities, whether based on religion or language, to have the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice. Article 341 and Article 342 also lays down various provisions for minorities to protect their social interest.

Protection of Economic Interest

Protection of Economic Interest has been laid in Article 46 of the Constitution which states that the State shall promote with special care, the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people, and, in particular, of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation. Special Financial Assistance Fund is charged from the Consolidated Fund of India each year as grant-in-aid for promoting the welfare of STs and the development of Scheduled Areas [Article 275(1)]. Article 335 laid down provisions for the claims of the members of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes shall be taken into consideration, consistently with the maintenance of efficiency of administration, in the making of appointments to services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or of a State.

Protection of Political Interest

A number of Constitutional Provisions exist for the protection and promotion of the interests of the socially disadvantageous groups. Article 244 and 329 govern the administration of the Scheduled Areas and Scheduled Tribes in any area. Article 330 and 332 provides for reservation of seats for SCs and STs in the House of People and Legislative Assemblies of the States.

Role of Indian Judiciary

The Indian Judiciary has played a pivotal role in the protection and promotion of minority rights through a series of landmark judgments. The Indian Judiciary has safeguarded the rights of 49% of people who are in minority and who are in a disadvantageous position.

State of Madras v. Champakam Dorairajan [1]

This case is considered as a milestone judgement for the protection and promotion of minorities.

Facts of the Case

The case was regarding the admission of students to the Engineering and Medical College of the State. The province of Madras has issued an order (known as Communal G.O.) ordering that seats should be filled in the selection committee strictly on the following basis i.e. out of every 14 seats, 6 were to be allowed to Non-Brahmins (Hindus), 2 to Backward Hindus, 2 to Brahmins, 2 to Harijans, 1 to Anglo Indians and Indian Christians and 1 to Muslims.

Ratio of the Judgement

The court held that Communal G.O violated the fundamental rights guaranteed to the citizens of India by Article 20(2) of the Constitution, namely that “no citizen shall be denied admission to any educational institution maintained by the state or receiving aid out of State funds on grounds only of religion, race, caste, language or any of them and was therefore void under Article 13 of the Constitution.

The Directive Principles of State Policy laid down in Part IV of the Constitution cannot be in any way override or abridge the fundamental rights guaranteed by Part III. On the other hand, they have to conform to and run as subsidiary to the fundamental rights laid down in Part III.

Jagwant Kaur v. State of Bombay [2]

Facts of the Case

In this case, an order of the collector of Poona under Section 5 of the Bombay Land Requisition Act for requisitioning some land in Poona for the establishment of a Harijan Camp was challenged as a violation of Article 15(1). The basis of the challenge was that a colony intended for the benefit only for the Harijans was discriminatory under the above Constitutional provision.

Ratio of the Judgement

It was held that Article 46 of the Constitution could not override a fundamental right. Consequently, the order was declared void.

1st Amendment of the Indian Constitution

The decision of the 1st Amendment had not come into effect until the time of the case Champakam Dorairajan and Jagwant Kumar. After the amendment, it was possible for the state to establish a Harijan colony to advance the interests of the backward classes. But till the amendment was not enacted as Article 15 stood, it was not competent for the state to discriminate in favour of any caste or community. Thus, these two decisions played a massive role which led to an amendment in Article 15.

The 1st Amendment incorporated Clause IV in Article 15 that empowers the State to make special provisions for the advancement of any socially educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes despite having Article 15(1) and Clause 2 of Article 29.

The object of the 1st constitutional amendment was to bring Article 15 and 29 in line with Article 16(4) which empowers explicitly the State to make special provisions for the backward classes in matters of public employment. The addition of Clause IV in Article 15 opened doors for several petitions before the court and the court has waived several petitions by interpreting Article 15 Clause IV.

Balaji v. State of Mysore [3]

It was held that the reservation could not be more than 50%. The classification of backward and more backward is invalid and caste cannot be the only criteria for a reservation because Article 15(4) talks about class and class is not synonymous with caste. So, other factors such as poverty should also be considered.

Devadasan v. Union of India [4]

The Supreme Court held that the “Carry Forward Rule” is unconstitutional. As per the carry forward rule posts that could be filled due to lack of candidates in backward classes would be filled by regular candidates but the same number of additional posts would be reserved in the next year. This caused the amount of reservation to go above 50%. Supreme Court held that the power of Article 16(4) could not be used to deny equality of opportunity for non-backwards people.

Indira Sawhney v. Union of India [5]

The judgement came in a 6:3 ratio, where minority opinion held that the Mandal Commission is unconstitutional because there is no limit set to implement the reservation policy.

The Majority opinion held that the Mandal Commission is constitutional and does not violate any provision of the constitution. The Supreme Court held that it was mandated that reservation ordinarily should not exceed 50%. The Supreme Court upheld the carry forward rule subject to the overall ceiling of 50%. It was submitted that this view is correct as the reservation is an exception to the general principle of equality as such an exception cannot exceed the main principle. The Supreme Court after considering the various aspects of reservation in a series of cases analysed, examined and reviewed the constitutionality of the reservation system under Article 15(4), Article 16(4) and Article 340 of the Indian Constitution.

In this case, the Supreme Court had answered several constitutional questions on the reservation. These questions are:

- Whether the term “any provision” in Article 16(4) must necessarily be made by the Parliament or Legislature?

The Supreme Court held that the very use of the word “any provision” in Article 16(4) is significant in nature. Article 16(4) uses the word ‘any provision’ for regulations of services, conditions by orders and rules made by the executive. Here, the Parliament or Executive can make the law only for those sections of the society who are not adequately represented. The Parliament or Legislature are not bound in affirmative to make provisions for equal representation in public employment.

2. Whether Article 16(4) is an exception to Article 16(1)?

The Supreme Court held that Article 16(4) is not an exception to Article 16(1), but is merely a way to do justice with Article 16(1). It is an extension of the Right to Equality.

3. Whether the concept of the creamy layer should be taken into account while implementing Article 16(4)?

8 out of 9 judges, in this case, held that the creamy layer must be excluded from the reservation made for OBCs. They gave the following reasons:

- For a group to be eligible for reservation, it must constitute a class. In order to be a class, the group must be homogenous. If the variations within it are vast, then it loses its character as a class.

- Unless the privileged within the class were excluded, they would never reap the benefits.

- Retaining groups who had transcended backwardness within a backward class would tantamount to treated unequal and violate Article 15.

- Whether the carry forward rule is constitutional or unconstitutional?

The Supreme Court held that the “Carry Forward Rule” is constitutional till the time it provides reservation up to 50%. Once the reservations exceed 50%, the rule becomes unconstitutional.

- Whether children of MPs and MLAs are excluded from the creamy layer?

Supreme Court held that it is the discretion of the State to examine the condition of children of MPs and MLAs. In pursuance to this Ramnandan Committee was formed. The committee held that the children of the present and former MPs and MLAs are excluded from the category of creamy layer and will come under the category of ‘Other Backward Class’ under Article 16(4).

- Whether the concept of reservation is anti-merit?

Supreme Court held that reservation is not about putting meritorious students behind instead it makes more of an egalitarian society. There are certain positions were the vacancies should be filled by merit only like a scientist, pilots, defence services, etc. Therefore, it cannot be said that the reservation is anti-merit.

- Whether the concept of the creamy layer should be applied to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes?

The Supreme Court was believed that the concept of Creamy Layer is applicable only to “Other Backward Classes”. The Schedule Caste has suffered the practice of untouchability more than other backward class and they are the more underprivileged class in comparison to other backward class.

- Whether the adequacy of representation in services under the state is subject to judicial scrutiny?

The Supreme Court held that the adequacy of representation of a particular class in the services under the state is a matter within the subjective satisfaction of the appropriate government. The judicial scrutiny in that is the same as in other matters within the personal satisfaction of an authority.

- Whether the backwardness in Article 16(4) should be both social and educational?

The Supreme Court held that the backwardness enshrined under Article 16(4) need not be both social and educational as in the case of Article 15(4). Article 16(4) is of a broader scope and social backwardness includes many other backwardnesses like economic backwardness, caste, etc.

K.C Vasant Kumar v. State of Karnataka [6]

The bench of Supreme Court consisting of Justice Chandrachud, Justice Desai, Justice Chinnappa Reddy, Justice Sen and other Justices held that reservations in favour of Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribes and Backward Classes must continue in the present form and for a period not exceeding 15 years. But the policy of reservation in the sectors of employment, education and legislative institutions should be reviewed after every five years or so.

The criteria to judge the Backwardness should be the Economic Backwardness and the reservations should not cross a reasonable limit of preference and discrimination.

Dr Fazal Ghafoor v. Union of India [7]

The Supreme Court held that there should not be any reservation in the field of Speciality. If therefore preference has to be given, it should not exceed 35% of the total quota.

Conclusion

Upon the analysis of all the cases stated above, it can be observed that the comparison of “socially and educationally backward classes” with the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes in Article 15(4) were to be construed as including such backward classes as the President may by order specify on the receipt of the report of the Commission appointed under Article 340(1) of the Indian Constitution.

The concept of backward classes is not relative in the sense that any class which is backward in relation to the most advanced class in the community must be included in it.

Hence, by a series of cases and constitutional provisions, it can be concluded that minority rights in post-independent India have been safeguarded, promoted and have been encouraged not only by the framers of the constitution but also by the present administrators, the legislators and the Judiciary.

References

- AIR 1951 SC 226.

- AIR 1952 Bom 461.

- AIR 1963 SC 649.

- AIR 1964 SC 179.

- AIR 1993 SC 477.

- AIR 1985 SC 1495.

- AIR 1988 SC 2288.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications