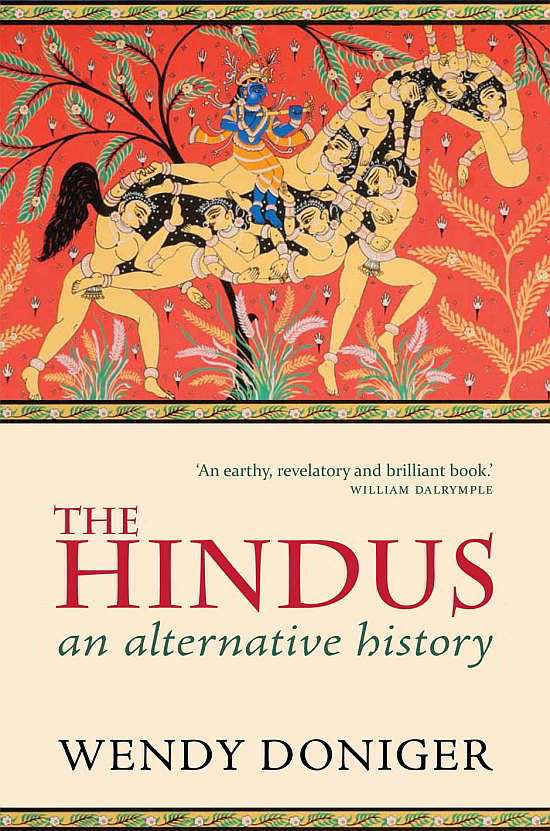

The release of Wendy Doniger’s recent book “The Hindus: An Alternative History”, which has been both revered and reviled by different sections of society, stirred up a huge controversy.

The book makes certain claims which certain segments of Hindus believe portray Hinduism in a bad light.

As a result, Shiksha Bachao Andolan filed a civil suit in the Saket District Court against Penguin India, the publisher of the book, and Doniger who is a professor of History of Religions at the University of Chicago Divinity School.

Finally, the plaintiff and Penguin India decided to enter into a settlement in accordance with which Penguin India agreed to immediately stop the sale and distribution of the book and to pulp all unsold copies.

This settlement raises several interesting, and somewhat troubling, socio-legal questions about the freedom of expression, rising intolerance within certain sections of society, the legal implications of a private settlement, role of publishers and utility of compulsory licenses.

Freedom of expression:

Many people have frowned upon Penguin’s decision to stop the distribution of the book on the ground that their decision is violative of the right of every individual to express their views freely, even if such views are not in conformity with the perception of the general public – a right embodied in Article 19 (1) of our constitution.

The book was withdrawn just to comply with the wishes of a certain faction of the society while the interests of a large number of readers who found the book informative and insightful were completely ignored.

Another noteworthy fact that lends credence to this argument is that the book was in its fourth reprint which indicates that it was doing very well.

It can be argued that this was a private settlement and, therefore, courts cannot be blamed for denying the author the freedom of expression or the readers the right to read the book and to discuss its various facets freely.

While this argument holds good in this case, it must be noted that most courts have not fully encouraged the rights of authors to express themselves freely.

Take, for example, the case of State of Maharashtra v. S. Damodar in which the Supreme Court made a suggestion that allegedly offensive passages be deleted from the concerned book so that the state government would be able to lift the ban on the book.

Similarly, in the case of Sri Baragur Ramachandrappa v. State of Karnataka, the Supreme Court decided to uphold the ban on P.V. Narayana’s Kannada novel named Dharmakaarana.

If we accept that the recent decisions of the Supreme Court are grounded in well-settled legal principles which allow courts to impose reasonable restrictions on the freedom of expression and to ban the distribution of obscene and offensive content, we have to answer an important normative question: Do we need to work towards changing the laws that allow different stakeholders to deny readers the right to read thought-provoking content?

Many thinkers argue that interpreting legal provisions pertaining to obscene and offensive content in such a way as to block the dissemination of books like The Hindus amounts to an abuse of the law.

However, as Apar Gupta eloquently argues in this article , if the law allows for such abuse, isn’t the law by itself abusive?

Rising intolerance:

Another related, but slightly different, concern which this case raises pertains to rising intolerance within certain factions of the society for views that do not conform to their own viewpoint.

It is pertinent to remember that this intolerance is not limited to factions within a particular religion but permeates different religious groups.

A case in point is the notification issued by the Government of India on 5th October, 1988 to prohibit the import of Salman Rushdie’s ‘The Satanic Verses’ under Section 11 of the Customs Act, 1952.

While it is essential to ensure that the sentiments of different communities are respected, it is equally essential to curb this kind of religious intolerance in a vibrant democracy like India.

Legal ramifications of private settlement:

As this was a private settlement, its validity cannot be challenged in the High Court. If the book had been banned by way of a notification of the government under Section 95 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, then its validity could have been challenged under Section 96 of the CRPC.

The negotiations which eventually led to the settlement were also conducted behind closed doors and completely lacked transparency. As a matter of fact, the public came to know about Penguin’s decision to withdraw the book from the market only after the settlement was leaked.

As a result, it would not be unfair to say that the parties involved in the lawsuit sealed the fate of such a popular book in such a way as to leave practically no remedies for readers to challenge their decision or to access the book.

Role of publishers:

This case poses an interesting question about the role of publishers in the book industry.

Specifically, should publishers merely act as conduits for authors in order to enable them to commercially exploit their works, or should they play a larger role by controlling the availability of the book in the market and by shaping the entire marketing policy for the book?

Although persuasive arguments have been made in favor of both these roles, empirical evidence reveals that publishers play the most instrumental role in shaping the future of any book.

For example, in another recent controversy about the publication of a book, the final decision to withdraw Jitender Bhargava’s book ‘The Descent of Air India’ was made by Bloomsbury, the publisher.

Similarly, the decision to withdraw another book by Doniger titled ‘On Hinduism’ was made by the publisher, Aleph Book Company.

Many thinkers argue that publishers often do not realize the inherent value of books and, therefore, are not in the best position to make this decision.

The author, they argue, can make the best decision as she is the creator of the controversial content and can best protect the interests of readers.

Compulsory licensing:

One possible remedy to ensure the widespread dissemination of the book that has been suggested by some thinkers involves the acquisition of a compulsory license from Penguin India by publishers who are interested in making the book available to the public.

However, the legal validity of such a remedy has been hotly debated because there is no express provision in the Copyright Act that can compel Penguin to issue such a compulsory license.

That being said, this option cannot be completely ruled out because courts have often favoured this remedy for protecting the concerns of the general public.

Other alternatives:

The Alternative Law Forum, on behalf of individuals describing themselves as ‘avid bibliophiles’ served a legal notice to Penguin shortly after the settlement asking them to either commence the publication of the book or to relinquish their copyright in the book in the public interest.

The notice further urges Penguin to return to the reading public what they have taken away from them – the right to read and dissent.

The notice states as follows:

Rescind on the contract that you have entered into with miscellaneous busybodies and immediately commence the publication of Wendy Doniger’s “The Hindus:

An Alternative history” and leave the messy act of pulping to those better suited for it -juicers and grinders…That in the event you choose to betray our sanguinity about your judgment by abandoning your Penguinity then you have effectively acknowledged that you are no longer interested in exercising your rights as the owners of the copyright in the said work and that you shall license the said work under a general

public license which will enable any person to copy, reproduce and circulate whether in print or electronically within the territory of India without the risk of infringing your copyright or hurting your sentiments.

block quote end

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications