This article has been written by Priyamvada Singh and further updated by Sneha Arora. It is a case analysis of S. Nambi Narayanan v. Siby Mathews and Others (2018), focusing on the arbitrariness of the police and examining whether reputation is considered a part of an individual’s fundamental right to life and liberty.

Table of Contents

Introduction

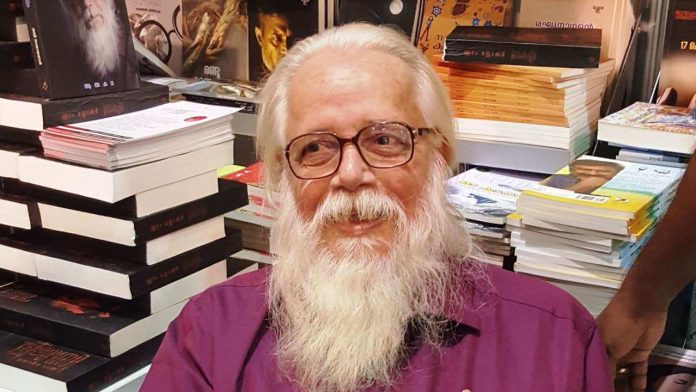

Few stories like that of the renowned scientist Nambi Narayanan highlight the alluring account of the violation of rights and stirring events. An eminent aerospace engineer and recipient of the Padma Bhushan name Narayanan, born on 12th December 1941, rose to prominence as a leader in the cryogenics divisions of ISRO. His career, marked by his dedication and innovation, took a drastic change in 1994 when he was charged with espionage. Although the allegations were proved to be mischief by the Supreme Court, the trajectory left a dramatic and lasting impact on his life. The case of Nambi Narayanan v. Siby Mathews and others (2018) provided him with compensation for the sufferings he endured. This legal battle aims at rectifying the injustice by granting and securing compensation for Narayanan. Before delving into the case analysis, let us try to understand the early life and career of Nambi Narayanan.

Early life and career of Nambi Narayanan

A native of Tamil Nadu, Nambi pursued his early education in Kanyakumari and went on to complete his degree in Masters of Technology at the College of Engineering, Thiruvananthapuram. His intention behind pursuing this degree was to get hired by Vikram Sarabhai at ISRO, of which Sarabhai was the chairman. After getting noticed, Mr. Sarabhai offered him a leave for his education at one of the Ivy League colleges in the USA. Eventually, NASA offered Nambi a fellowship, and he also secured admission to the prestigious Princeton University. He studied chemical rocket propulsion there and created a record by completing his masters in merely 10 months. Needless to say, the administration noticed his intelligence and offered him a job in the United States. However, Nambi longed for his homeland. He turned down the job and returned to India.

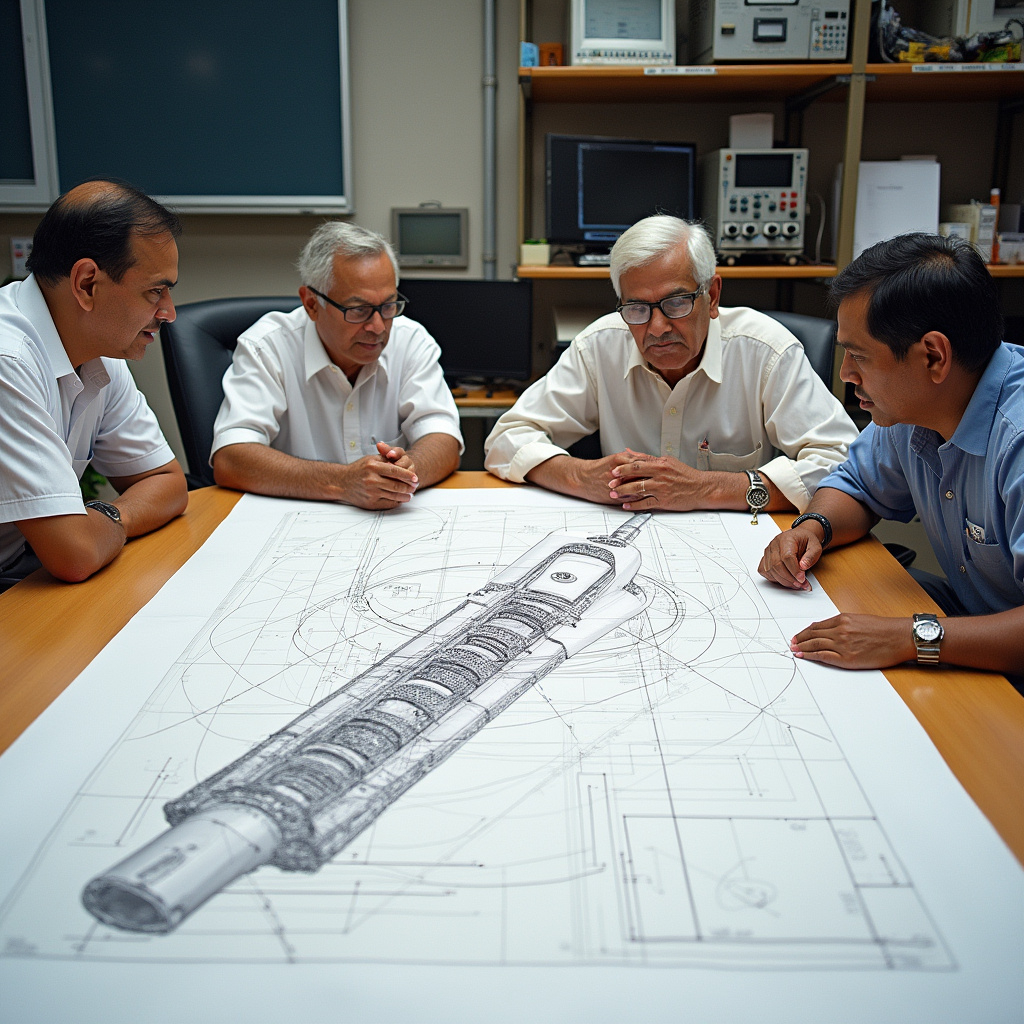

At a time when ISRO was dependent on solid propellants in rocketry, Nambi returned with knowledge of liquid propellants. In the 1970s, APJ Abdul Kalam was working on solid motors. He was joined by Nambi, who introduced liquid fuel rocket technology to the Indian rocketry scenario. For this, he was provided with an incentive by the then ISRO chairman, Satish Dhawan, who recognised the spark in his ideas. Eventually, India witnessed its first successful thrust engine in 1975. Nambi Narayanan proved to be a great asset to the organization and, in turn, to the country. In 2019, he was awarded the Padma Bhushan.

Background of the case

In 1992, India agreed to pay Russia a hefty sum of Rs. 235 crore for the transfer of technology on how to produce cryogenic fuel-based engines. Cryogenic fuels are those that require very low temperatures to keep them in a liquid state. It was decided that Russia would provide two such engines in working condition, along with the technology. However, the then President of the United States of America, George W. Bush, decided to write to Russia about his objections regarding the same. The President of Russia at that time, Boris Yeltsin, feared getting sanctioned by the G5 group and, hence, refused to provide India with the technology. The United States had seemingly won this war of monopolies.

In another attempt at the battle, India suggested a strategy whereby no formal technology transfer would occur, and instead, four cryogenic engines would be replicated. Despite initiating the plan, it failed to yield the intended outcomes due to the spy scandal involving Nambi in 1994.

Details of the case

- Case Name: S. Nambi Narayanan v. Siby Mathews

- Appellant: S. Nambi Narayanan

- Respondent: Siby Mathews

- Bench: Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, Justice A.M. Khanwilkar, and Justice Dipak Misra

- Case Type: Civil Appeal

- Date of Judgement: 14 September 2018

- Citation: SC (2018) 10 SCC 804

Facts of the case

In October 1994, intelligence officials arrested two Maldivian women, Mariam Rasheeda and Fauzia Hassan, for overstaying their visas in India and alleging that they were spies. This led the officials to Nambi. However, upon searching Nambi’s residence, no incriminating evidence was found, and the police left empty-handed.

In November 1994, Nambi Narayanan, along with four others, was arrested for leaking vital rocket information to Pakistan. Within 24 hours, Nambi was presented in front of a Magistrate, who asked him to confess to his crimes. Nambi refused to do so and was sent to custody for 11 days. In total, Nambi was made to spend 50 days in judicial custody with a hardened serial killer. Furthermore, people gathered in front of the station to shout slurs such as “traitor” and “spy”. He was subjected to third-degree torture. He was brutally beaten. He was even made to stand for 30 hours to force him to confess to his crimes and falsely accuse higher officials of helping him through the espionage. In January 1995, all the accused scientists were released on bail. In April 1996, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) asserted before the Kerala High Court that the espionage case was false and that there was no evidence to support the charges, and in May 1996, all the accused were discharged.

Two years later, in 1998, the charges were dropped when the CBI decided to step in. However, Nambi had to leave his job of working on the cryogenic fuel motor and was forced to take up a desk job. The phoney case had cost him his career and the country a significant development in rocket science. In May 1998, the Supreme Court awarded compensation of Rs. 1 lakh to Mr. Narayanan and the others concerned. The brunt of the compensation was to be borne by the Government of Kerala by way of vicarious liability.

In 1999, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) asserted that the government of Kerala had damaged Narayanan’s distinguished career in space research. The NHRC ordered the Kerala government to pay Nambi Rs. 1 crore in damages for hurting his reputation. The NHRC claimed that the government of Kerala was vicariously liable for the actions of its police officials. However, the Kerala High Court only agreed to a compensation of Rs. 10 lakh. After 11 years, a probe revealed that even this Rs. 10 lakh had still not been paid to Nambi. Meanwhile, Siby Mathews, the official involved in the false implications, was appointed as the Chief Information Commissioner of Kerala.

Legal aspects involved

Malicious prosecution

Malicious prosecution refers to the wrongful initiation of criminal or civil proceedings against an individual with malice or without reasonable or probable cause. It certainly involves the malicious intent of an individual towards another person to harm, harass, or unfairly target someone by exposing an individual to legal proceedings. In a malicious prosecution claim, the burden of proof falls upon the plaintiff to show that the defendant’s allegations are false and wrongful legal action was initiated against him.

In Madan Mohan Singh v. Bhrigunath Singh and Ors. (1952), it was held that no person shall be jailed on the basis of false charges. In this case, a person was jailed for 40 days due to false allegations. It was held by the Supreme Court that this was a matter of malicious prosecution.

Reputation as a part of the right to life and liberty

The Constitution of India guarantees each citizen a fundamental right to life and liberty under Article 21. This right has been, time and again, expanded to include many elements of a human being’s life. In the case of Kharak Singh v. State of UP and Ors. (1962), the Supreme Court ruled that the concept of “life” means something more than biological survival. It involves all the enjoyment and facilities that an individual requires for a good life. Therefore, any action that deprives an individual of the enjoyment of his rights and life is prohibited by the law. This includes everything that is physical harm, mental harm, amputation or mutilation, or any damage to the organ of an individual through which a person interacts and works with the external world, to be safeguarded by the law.

The reputation of a person is directly and proportionately related to the quality of his life. The right to life is a fundamental right guaranteed under the constitution, and the reputation of a person is an unmissable facet of the same. The right to the enjoyment of a private reputation, unassailed by malicious slander, is of ancient origin and is necessary to human society. As reputation is an essential part of an individual’s life, it is the duty of the government and the state to ensure that no individual is restricted from protecting his reputation. In the present case, the reputation of the former scientist was tarnished due to forged and fabricated accusations against him by the Kerala police. In State of Bihar v. Lal Krishna Advani and Ors. (2003), in order to discuss the communal disturbance that took place in Bhagalpur, Bihar, a committee of two members was appointed for the same purpose. The remark made by the committee in their report challenged the reputation of the respondent in the eyes of society. The respondent was not given a fair chance to prove his innocence and to maintain his reputation. The Supreme Court held that the rights of the respondent had been infringed; thereby, he was entitled to the right to reputation under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. Additionally, the court granted him compensation for the violation of his fundamental rights. Furthermore, in the case of State of UP v. Mohammad Niam (1963), it was held that the following tests are to be laid down while dealing with the question of a defamatory statement against any other person.

- Whether the party whose conduct is in question before the court had sufficient opportunity to prove his innocence.

- Whether there is credible evidence regarding the disgraceful remarks against that person or party.

- Whether the outcome of the case must consider and address the mentioned conduct as an essential aspect.

In the present case, Nambi Narayanan’s reputation was severely impacted and tarnished, which not only affected him but also his family, who suffered from the critical consequences. Apart from that, he was also not provided with sufficient opportunity to prove his innocence.

Arguments of the parties

Appellant

The appellant in this case asserted several arguments stemming from the accusations of malicious prosecution by the Kerala Police in the espionage charges.

The appellant claimed that the Kerala Police’s prosecution against him was malicious on the following grounds: it led to a severe blow to his career and standing as a renowned ISRo scientist, which affected his work, savings, honour, and ultimately, the peace of his family. It also created severe complications in terms of the technological advancement of India’s space research.

It was also pointed out that the CBI, who took over the investigation of the case after looking into it for 18 months, recommended the case against the appellant be closed since there seemed to be no justifications behind the allegations. The CBI report also highlighted lapses in duty by the Kerala Police and recommended the Government of Kerala to take action against the concerned officers for the same. Notwithstanding these findings, the Government of Kerala failed to take action against those erring officials and instead directed all their attention towards investigating the appellant and even constituted a Special Investigation Team for the purpose.

The appellant highlighted that this Court had, at an earlier instance, agreed that the prosecution against him was malicious. The National Human Rights Commission had also criticised the actions of the government of Kerala. The appellant held that the High Court of Kerala was wrong in supporting the government. Moreover, the appellant sought compensation for a constitutional tort and requested the formation of a committee to address the actions of the officials accountable for the misconduct.

Respondents

The respondent, Siby Mathews, firstly contended that the appellant’s claim of the country being stripped of its benefit, since he would have made notable contributions to cryogenic technology, is not credible. This is due to the fact that, immediately after Mariam Rasheeda’s arrest, the appellant resigned on his own will. Hence, these claims made by him must be purely for the purpose of gaining sympathy.

The respondent stated that the investigation was monitored by high-ranking officials, and he was kept well-updated regarding the same too. The respondent also added that on the day of the appellant’s arrest, he had requested the case be transferred to the CBI, which implies a lack of prejudice. The investigation was conducted in a just manner, and all the evidence pointed towards the appellant being engaged in espionage activities.

It was firmly held by the respondent that neither he nor any of the other police officers tortured the appellant. Previous High Court rulings on this matter stand as evidence. The respondent transferred the case to the CBI instead of conducting the investigation himself, which quashes any claims of torture by the police. Furthermore, the Intelligence Bureau was involved in the case before the Special Investigation Team was constituted.

It was stressed that there existed sufficient evidence to prove that the appellant was engaged in espionage activities. Furthermore, his arrest had become necessary because, after his voluntary retirement, he intended on leaving the country. Referring to the CBI’s report, which stated that no incriminating evidence was found, the respondent mentioned that 235 documents had been recovered from the homes of the accused, and these need to be investigated further.

The respondent further stated that he had conducted the investigation for a mere 17 days before transferring it to the CBI, and hence, the onus of updating the media was on them. Holding the Special Investigation Team responsible for any misconduct in the investigation after it was transferred to the CBI is not reasonable.

The Intelligence Bureau officials, who were primarily accused of torture, escaped accountability. Consequently, the respondent argued that accusing him and the Kerala police of torture would not be just. Moreover, the High Court had merely directed the state government to reconsider the matter and had not mentioned anything specifically about torture. The appellant had also not raised any complaint of torture before the Chief Judicial Magistrate. Moreover, of the 50 days the appellant spent in custody, he was under police custody for only 5 days, with the remaining 45 days being under the custody of the CBI.

Central Bureau of Investigation

The respondent on behalf of the CBI contended that although the shortcomings of the Kerala police with respect to the investigation were highlighted, the Government of Kerala failed to take any action against them. The CBI held that it would be a grave mistake if the government was not called out for this failure. It was argued that the Kerala police’s actions were criminal in nature. Although the report was merely a recommendation, the Government of Kerala should have taken it into serious consideration and taken the necessary steps that would respect a person’s rights as well as the essence of the Constitution of India. They referred to the case of Japani Sahoo v. Chandra Sekhar Mohanty (2007) and stated that the Government of Kerala could not hide their lack of action under the disguise of a delay. Ensuring justice for the appellant would include both paying compensation and dealing with the police’s conduct.

In Punjab and Haryana High Court Bar Association v. State of Punjab and Ors (1994), the court stressed the significance of carrying out investigations to instil people with a sense of faith in the justice system. On the basis of this, the CBI stressed that the Kerala police’s conduct must be thoroughly investigated.

Judgement in Nambi Narayanan v. Siby Mathews and Others (2018)

The Supreme Court, upon reviewing the CBI’s closure report, noted that the appellant had been arrested and detained for nearly 50 days. Therefore, the Court should consider the issue of granting compensation. The report submitted by the CBI commented that, as the accused denied any involvement in the espionage activities, there was no such evidence found to indicate that the accused was a mischief or that he was trying to gain sympathy out of the services he provided to the nation as contented by the respondent. Also, the CBI report submitted many lapses, errors, and omissions on the part of the Kerala Police in their investigation process. Therefore, allegations of espionage were not truly proven, and so it was directed for the discharge of the accused and the return of the seized documents. From the closure report provided by the CBI, the Supreme Court was of the view that harassment and the mental torture endured by the appellant were obvious.

Rationale behind the judgement

The Court accepted the CBI report under K. Chandrasekhar, Mariam Rasheeda, v. the State of Kerala & Ors, (1998), and observed that the ISRO did not have a system of classifying documents and followed an open door policy for access to documents. During the investigation, it was found that documents were regularly issued to various divisions, and after a scientist’s transfer, all copies of the drawings remained intact. Senior scientists like Nambi Narayanan had access to these documents, but there was no evidence of them being issued to him or being passed on to third parties. Therefore, there is no basis for further investigation into alleged espionage activities within ISRO, as no classified documents were found to be stolen or missing. The jurisdiction for any investigation into this matter would lie with the Kerala Police.

The Court further stated that the prosecution by the state police was malicious and led to harassment and anguish for the appellant. The state police transferred the case to the CBI after arresting the appellant and others. Despite the transfer, the initial prosecution lacked proper grounds and was baseless, unlike a case where the accused is eventually not found guilty after the trial. The Court held that the actions of the state police were unjustified. It severely jeopardised the liberty and dignity of the appellant, as under Article 21 of the Constitution. Therefore, compensation was deemed to be required for such a violation.

The case of DK Basu v. State of West Bengal (1996) was referred to, wherein it was stated that “torture” does not merely include physical pain but also mental agony inflicted upon an individual. It includes psychological trauma, which could, in turn, hamper a person’s personality and dignity. The Court stated that custodial torture must be considered as grave as any other physical or mental torture. It is a violation of human dignity as well as a step backwards in terms of the standards of human morality. The Court observed that the mental trauma experienced by the appellant under police custody is of significant concern, even if no physical harm was caused to him.

In the case of Jogendra Kumar v. State of UP (1994), the court emphasised the growing scope of human rights and the increasing crime rate. It stresses upon the need to strike a balance between individual rights and collective societal interests with respect to the concept of arrest. Therefore, the court emphasised the importance of upholding human rights while also ensuring public safety.

The Court was of the view that reputation is an important aspect of personal security and is protected under the Indian Constitution. It referred to Kiran Bedi and Ors. v. Committee of Inquiry and Ors. (1998), wherein it said that the right to a good reputation without being subjected to malicious and false talk has been a vital part of society. A good reputation falls under the ambit of personal safety and is protected under the Constitution. The same was reiterated in Vishwasnath Agarwal v. Sarla Vishwasnath Agrawal (2012).

The Court condemned the excessive use of force by the police and referred to the case of Delhi Judicial Service Association v. State of Gujarat (2019), wherein the functions of the police were stressed. These include the investigation of crimes, the apprehension of offenders, and maintaining law and order. Despite this, police misconduct is witnessed. While the police hold the authority to arrest without a warrant, they must do so without violating the fundamental and constitutional rights of a person.

In Sube Singh v. State of Haryana (1993) and Hardeep Singh v. State of Madhya Pradesh (2011), the Supreme Court affirmed the award of compensation as an appropriate remedy for infringement of fundamental rights under Article 21. The amount of compensation depends on the circumstances of the case and does not prevent the person who has been wronged from pursuing further compensation through criminal or civil proceedings.

Considering these principles, it is evident that the appellant, a renowned scientist at ISRO, endured immense humiliation. Such a treatment not only violates his fundamental rights, notwithstanding the existing civil suit, but also warrants compensation under public law. The wrongful imprisonment, malicious prosecution, and humiliation faced by the appellant must be taken into consideration.

Final verdict

In light of the CBI report in K. Chandrasekhar v. State of Kerala (1998), the Supreme Court deemed it necessary to award compensation to Nambi Narayanan. Accordingly, it ordered the Government of Kerala to pay compensation of Rs. 50 lakh to Nambi Narayanan within eight weeks. The appellant was also allowed to pursue the civil suit filed for additional compensation. Additionally, on the basis of the appellant’s recommendations, the Court constituted a committee headed by Justice D.K. Jain with the aim of dealing with the accountability of the officials responsible. This Committee, with representatives of the Central and State governments, shall operate from Delhi but may hold meetings from Kerala as needed. The Central Government shall provide funding for the logistical support and functioning of the committee.

Impact of the judgement

In recent developments with regard to the case law S. Nambi Narayanan v. Siby Mathews, there has been increased inspection and scrutiny of the accountability of the government and safeguarding individual rights. Following the Supreme Court landmark judgement in 2018 to award compensation to the Nambi Narayanan for the wrongful arrest and accusations against him, there have been certain provisions and reforms so as to avoid future miscarriage of justice. Additionally, there have been certain discussions so as to preserve and protect individual rights and to ensure the integrity of investigations and the accountability of the investigating officers and the government officers. This case continues to serve as a catalyst to frame the legal system and machinery in an organised form and to ensure that every individual receives fair and just legal services and assessments.

Critical analysis

The ISRO espionage case, also known as the S. Nambi Narayanan case revolves around the wrongful arrest and retention of two scientists, S. Nambi Narayanan and D. Sasikumaran, in 1994 on charges of espionage. The case involves serious complexities and controversies, with forced charges, fabricated evidence, and political interference. In 1996, the Kerala High Court dismissed the case, stating that it involved many procedural irregularities. In 1998, the Supreme Court upheld the case and directed the Kerala government to pay for the damages caused to Narayanan’s reputation.

This case raised several legal and ethical controversies, including the misuse of power by enforcement agencies and investigating officers. It highlighted the importance of due process of law and the need for transparency and accountability of the government in its actions. Furthermore, the fabricated evidence and tormentation as seen with respect to Nambi Narayanan highlight the dangers of a criminal justice system that prioritises convictions over the just and fairness of the case.

Therefore, the ISRO espionage case is a stark reminder of the challenges faced by a society with respect to maintaining justice. It underscores the significance of a fair and impartial criminal justice system to safeguard individual rights while also upholding public security.

Conclusion

Even though Nambi has been paid his damages monetarily, the past 24 years of his life cannot be retrieved. The country suffered great damage at the hands of a few police officials, whose actions severely affected Nambi, his family, career, reputation, and self-respect. Those who caused it were free to go without any repercussions.

It is imperative that the arbitrary use of power at the hands of the police be curbed. There must be a clear code for them to follow, and evidence must be taken into serious consideration before subjecting a person to humiliation and torture, both physically and socially. A learned and reputable man such as Nambi certainly did not deserve his fate. It must be ensured that no one else suffers anything inhumane like this again. The damage to reputation he suffered during the prosecution severely affected his career and his fame. An individual’s reputation is an integral part of their right to live with dignity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Who were the two other accused in the ISRO spy case?

The ISRO case involves the scientists S. Nambi Narayanan and D. Sasikumaran. The other accused in the case include former IB officers CRR Nair, GS Nair, KV Thomas, PS Jaiprakash, John Punnan, Baby, Dinta Mathiyas, VK Maini, Mariam Rasheeda, Fauzia Hassan, and SK Sharma.

What was the evidence presented against the other accused in the ISRO case?

The evidence presented against the other accused in the case included a diary written in Dhivehi, leakage of information with the foreign national, and alleged involvement in logistics and payments for the transfer of the documents.

What was the role of the Indian media in the ISRO spy case?

The Indian media played a significant role in the ISRO spy case, with many news organisations sensationalising the allegations made against the scientist. The ISRO spy case was covered by various media outlets, including the Malayala Manorama, Mangalam Mathrubhumi, and Asianet.

References

https://www.pathlegal.in/SC-Judgement-S-Nambi-Narayanan-Siby-Mathews–blog-1989738

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications