This article is written by Abhijith S Kumar.

Introduction

Legal fiction or fictio juris is a device by which law deliberately departs from the truth of things whether there is any sufficient reason for the same or not. That is, at times law may have to identify certain facts as something which may go against the actual manifestation. In such situations, law holds fast to fictio juris or legal fictions whereby it depart from the truth and believe something else. Corporate personality is one such identified legal fiction whereby a separate identity apart from its individual members are given to a company. Company as described in Stanley, Re[1] imply an association of persons for some common object or objects. Thus it is actually the men who forms the association who carry out the activities. But law identifies their individual personality as well as a separate personality for the association independent of its members primarily to limit liability of the members of the company. Thus corporation is an artificial being, existing only in the contemplation of law.

This idea of separate legal entity of the company was identified and well established in the case of Salomon v. Salomon & Co. Ltd[2]. The principle of corporate personality apart from associating a separate entity independent of its members, also limit the liability of its members, confers with perpetual succession, allows transferability of shares, enables to have a common seal, entitles the company to enter into transactions and to purchase, hold, and divest property in its name and also makes it competent to sue and to be sued in the company name.

But incorporation also has its disadvantages, the prominent one being instances of lifting of corporate veil. The privilege as conferred by Salomon is one that enables company to enjoy limited liability whereas at the other end of the spectrum, the law might tackle the limited liability principle and make the people behind the company running the show liable for the obligation of the company in certain cases. A comprehensive understanding may be arrived through the acknowledgement of the lifting of corporate veil principle.

The project intends to analyse this concept of law. The project discusses the concept and its evolution by tracing the development under common law and the conflict with the Salomon rule and the followed decisions. The instances of lifting of veil as identified under statute and judicial interpretations are also looked into with special emphasis on the acceptance of various grounds under Indian jurisprudence.

Lifting of Corporate Veil – Concept

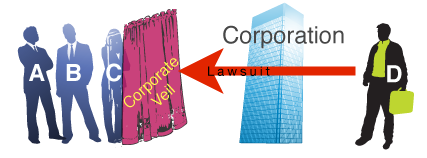

The corporate veil is the term given to the imaginary barrier that separates the company from those who direct it and from those who own it. The chief advantage of incorporation is, of course, the separate legal entity of the company and limited liability. But in reality, it is the persons who form the association that carry out the business on behalf of the incorporated corporation. That is, though in fiction of law, a corporation is a distinct entity, in reality, it is an association of persons who are in fact the beneficiaries of the corporate personality.[3] Thus the attribution of legal personality on incorporation is a privilege given to the companies.

But there may arise instances where under the shade of this, fraudulent or illegal acts are committed. As artificial persons are incapable of doing anything illegal or fraudulent, the façade of the corporate personality have to be removed to identify the persons who are really guilty. This principle which goes in contrary to the general rule under Salomon is known as ‘lifting of corporate veil’. Thus lifting of corporate veil is resorted to know the realities under the corporate veil. Though it is in contrast to the rule in Salomon, it do not renders the same as invalid. The principle presupposes the existence of corporate identity, which may be lifted for the interests of the members in general or in public interest to identify and to impose liability on those who misuse the privilege conferred on them. Where the judiciary or the legislature have decided that the separation of the personality of the company and members are to be maintained, the veil of incorporation is thus said to be lifted.

Thus the piercing (or lifting) of the corporate veil refers to the possibility of looking beyond the company framework to make the members liable, as an exception to the rule that they are normally shielded by the corporate law.[4]

Evolution of the Concept

Since Salomon decision, the courts have come across many situations wherein they were called upon to apply the principle of separate legal person in what might be called different situations. Though not as a general rule, the courts were resorting to the contrary of what had been laid down in Salomon on various grounds whenever it seemed just to do the same or whenever special circumstances demanded the same. Thus it leaves no room for doubt with regard to the factum of identification and acknowledgement of the concept of ‘lifting of corporate veil’, though the recognition of a concept going against or which is anti-directional to the law as expounded by the House of Lords made space for various other contradictions and fogginess in the legal system and jurisprudence.

The explanations as given by courts while resorting to the adoption of the theory of lifting of corporate veil often led to issues. Many attempts were made in providing explanations for the instances under which the courts may lift the corporate veil disregarding the separate corporate entity. But none of these were really satisfactory. Attempts have been made to classify the various instances under categories such as where there is fraud, where there exists employment issues, where there exists impropriety issues, when the company is merely a sham or façade, or where a group of companies act as a single economic entity and under these instances, the courts may lift the veil to see what the realities are.

In 1990, Ottolenghi resorted to classifying the various instances into categories based on the approach analysing the trend of judicial interference in such matters. Where the veil of incorporation is lifted to get member information, the same fell under the head ‘peeping’. At certain times, the veil had to be ‘penetrated’ to disregard the concept of limited liability so as to fix liability upon the members of the company. ‘Extending’ was resorted where a group of companies were to be treated as one legal entity and ‘ignorance’ referred to the non-recognition of company at all.

The evolution of the concept and instances of ‘lifting of corporate veil’ is traced down through three phases by Alan and John[5]. The ‘Classical Veil Lifting’ (1897-1966) saw courts falling back heavily upon the Salomon ratio. The House of Lords decision in Salomon dominated in this period thereby acting as a restraint on veil lifting. But gradually, the courts began to lift veil of incorporation so as to tackle certain identified exceptional circumstances. One of the earlier decisions in this regard was Daimler Co. Ltd. v. Continental Tyre and Rubber Co. (Great Britain) Ltd.[6] wherein the court lifted the veil to determine as to whether the company in question was an ‘enemy’ or not. Followed were the decisions in Gilford Motor Co. Ltd. v. Horne[7], Re Bugle Press[8] and John v. Lipman[9] identifying façade and sham as grounds for lifting the corporate veil. It is worthy to note that even when the courts lifted veil at instances, this was not generally resorted to and was done only in exceptional cases. The courts were placing strong reliance on the Salomon decision and chose not to give away with the limited liability principle unless exigencies forced them to do so.

Whereas, by 1960s, the courts were increasingly demonstrating a tendency to free themselves from the old precedence which they saw as increasingly unjust. Identified as the ‘Interventionist Years’ (1966-1989) this phase probably saw the highest rate of intervention made by the courts to treat the separate personality of companies as an initial negotiating position which could be overturned in the interests of justice. Relying vehemently on the Littlewoods Mail Order Stores v. IRC[10] decision that laid down that the courts may do away with the Salomon rule to ensure justice and for that reason, the courts may look beyond the veil, courts frequently resorted to lifting or piercing of corporate veil. It won’t be wrong to state that this led to uncertainty with regard to the law relating to corporate personality.

The 1990 decision of Adams v. Cape Industries Plc[11] of the Court of Appeal finally put the uncertainty to rest. It went on to discuss the conflict between the classical and the interventionist view and concluded in favour of the classical view. This phase identified as ‘Back to Basics’ (1989-present) took a U-turn to the classical view holding that the Salomon rule cannot be disregarded merely on the ground that justice so requires. There can be identified grounds under statute or contract or as identified under judicial interpretations which are well settled to lift the veil; but the same cannot be seen as a general rule. The rule of lifting of veil is strictly to be applied to ‘you know it when you see it’ cases. Furthermore, Woolfson v. Strathclyde Regional Council[12] insisted on the application of the rule in special circumstances alone and where the motive is well established.

Thus Adams significantly narrowed the ability of courts to lift the veil in contrast to where the Court of Appeal would lift the veil to achieve justice irrespective of the legal efficacy of the corporate structure.

Instances of Lifting of Corporate Veil

The circumstances under which the courts may lift corporate veil may broadly be grouped under the following heads: (1) Under statutory provisions, (2) Under judicial interpretations.

4.1.Under Statute

The corporate veil may be lifted or pierced under certain instances and some of these are explicitly given within the statues enabling the court to do the same. In Cotton Corporation of India Ltd. v. G.C. Odusumath[13] laid down the rule that the courts can lift corporate veil only when provisions for the same is expressly provided within the statute book or only if there are any compelling reasons. The classical view of lifting of veil also is in line with this approach. It is in this context that an understanding of such provisions gains relevance.

The Companies Act, 2013 provides for the following provisions enabling courts to lift the corporate veil.

Often, courts lift the corporate veil to fix liability and punish the members or the directors of the company. Section 7(7) of the Act provides one such provision. Where the incorporation of a company is effectuated by way of furnishing false information, the court may fix liability and for this purpose, the veil may be lifted.

Section 251(1) also is a penal provision. The Act asks for the submission of an application for the removal of name of the company from the registrar of the companies. Any who make fraudulent application is fixed with liability under thus section.

Section 34 and 35 of the act also enable the courts to lift the veil of incorporation to fix liability. When prospectus includes misrepresentations, the court may impose compensatory liability upon the one who misrepresented.

The Companies Act provides that in cases of issue of shares to public, in the event of the company not receiving the minimum subscription in 30 days of issuance of prospectus, the company is bound to return the application money. Section 39 imposes penalty on failure to do this within 15 days’ time period.

There might be instances where the investigators or the concerned authority or the government may have to look into the affairs of a company for the purpose of evaluating whether it is a sham and the realities under its corporate veil. Section 216 is the enabling provision to carry out this purpose. For manifesting the same, the courts may pierce the veil and the same is protected. Section 219 of the Act also does the same function.

The chances of members resorting to fraudulent conduct is high particularly during the course of winding up of a company. This is condemned under Section 339. To evaluate the prospects of the same, the veil may be lifted.

Section 464 of the Act imposes penal liability on the members and directors of the company when the requirements of incorporation are not complied with. Incorporation brings with it added privileges and therefore the law imposes preconditions on its enjoyments in the form of statutory compliances, the non-observance of which may attract liability. Thus the factum of manifestation of the same may be investigated into and for this purpose, the veil may be lifted.

Besides Companies Act, 2013, certain provisions of Income-Tax Act and Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, 1973 also enables the lifting of corporate veil.

4.2.Under Judicial Interpretation

The principle of corporate veil as a concept got evolved post Salomon under Common Law. The classical approach had identified certain categories of instances under which the veil of incorporation may be lifted. This includes the agency argument, single economic entity argument, façade or sham, impropriety and determination of enemy. It is noteworthy that the same had been identified and acknowledged in India too.

4.2.1 Instances identified under Common Law and the recognition of the same under Indian Law

Jones v. Lipman[14], (1962) I.W.L.R 832 is a classic example where the veil was lifted on the ground of fraud or improper conduct (impropriety). In this case, A made a sale agreement with B. But before its completion, A transferred the property in question to a company created by him in which he and his clerk were the only directors cum members. This led to a litigation wherein in the court found out that his action had malice tint attached to it whereby he tried to evade claims of specific performance.

In Re: R.G Films Ltd.,[15] identified the agency argument. In this case, an American production company decided to produce a film in India under the banner of a British Company. When application was made for its certification as a British production film, the application was rejected. The court in this instance, applied the doctrine of lifting of corporate veil to understand the intricacies of the issue. The court came to the conclusion that the British company was merely an agent as the majority investment came from the American company thus holding that the stand taken by the certification authority was right.

Company being an artificial person cannot be an enemy or a friend. But in the instances of war, it may become necessary to lift the veil to see whether the actions of the company is actually that of a friend or an enemy. This principle of determination of enemy came to be established in Daimler Co. Ltd. v. Continental Tyre & Rubber Co.[16]. In Connors Bros. v. Connors[17], the court found out that the director having the de facto control of the company being the resident of Germany, an alien country, allowing the proceedings of the company would result in giving money to the enemy country. Thus the company was held to be an enemy.

Façade or sham refers to that situation where what is seen on the face is not the reality, rather it is the contrary of it. Subhra Mukherjee v. Bharat Coking Coal Ltd[18]. involved an issue with regard to a private coal company. The company on getting intimation as to nationalisation of the company, transferred the immovable assets of the company to the wives of the directors. The court on lifting the veil of incorporation concluded that the transaction was not made in the interests of the company, but in the interests of the directors and therefore is a sham.

It is not barred under corporate law to have a subsidiary company. The holding company may or may not have complete control over the subsidiary company. Irrespective of this fact, the law identifies separate legal identities for both the holding and the subsidiary company. But at times, on lifting the veil, it had been found out that there might be instances where both the companies may be identified as a single economic entity.

In Merchandise Transport Ltd. v. British Transport Communications[19], a transport company made application for licenses and on rejection of the same, they made applications in the name of its subsidiary company. The court found out that the subsidiary company conducted no business nor had any income. The same was created merely for obtaining the licenses and therefore both the companies were acting towards a common cause. Thus they were identified as a single economic entity. J.B Exports Ltd. v. BSES Rajadhani Power Ltd.[20] also identified the same principle.

4.2.2. Other grounds evolved under Indian Jurisprudence

The following are those instances under evolved under Indian Jurisprudence which enables the courts to lift the corporate veil. The Supreme Court of India had acknowledged this principle long back. While LIC v. Escorts Ltd.[21] was in line with the classical view, U.P v. Renusagar Power Co.[22] went in favour of the interventionist approach. But it is worthy to note that the though Renusagar is not overruled, this is not the rule to be followed. The Apex court from time to time have reiterated that the lifting of corporate veil can be resorted to only in exceptional circumstances and that the same cannot be treated as a general rule.

The specifically identified grounds hereinafter mentioned does not go against the classical idea. The statement that the same goes in contrary to the classical idea would be an untenable statement. The same were evolved under varying circumstances, but essentially falling under the identified classical heads, thereby forming subsets of the same.

In Re. Dinshaw Maneckjee Petit[23], a wealthy man enjoying large dividend and interest from income formed four companies and transferred all of his interests and dividends to the companies. The companies had no other business and transferred back all the investments made to the assesse by way of pretended loans. Essentially falling under façade and impropriety, the court held that the same was done to evade taxes upon lifting the veil.

In The Workmen Employed in Associated Rubber Industries Ltd., Bhavnagar v. The Associated Rubber Industries Ltd., Bhavnagar[24], the company in question created a wholly controlled subsidiary company which performed no business, but received dividends from the principal company. The court upon lifting the corporate veil came to the conclusion that this action was purported in order to split the dividends so that a reduced bonus amount may be given to the employees. This was found as an act in order to avoid a welfare legislation and the same was identified as a valid ground for lifting the veil of incorporation.

In cases of economic offences, a court is entitled to lift the veil of corporate entity and pay regard to the economic realities behind the legal façade. In Santanu Ray v. UOI[25], the company was alleged of violation of Section 11 of Central Excise and Salt Act. The court went on to hold that corporate veil could be lifted to know which of the directors was concerned with evasion of excise duty for reason of fraud, concealment or wilful misrepresentation or suppression of facts.

Contempt of Court as identified in Jyoti Limited v. Kanwaljit Kaur Bhasin,[26]is another identified ground to lift the corporate veil. In this case, a firm of two partners agreed to sell property, which got cancelled in a subsequent stage. This was followed by litigation wherein the court gave an injunction order restraining all forms of transactions with regard to the property in question. But the company went on and flouted a private company into sale. It was held that on lifting the corporate veil, it could be deciphered that the company was promoted solely by respondents and therefore the interests of the company were that of merely the two. Thus the sale amounted to contempt of court and the members were made liable.

Conclusion

Wherever the members of a company violates any statutory provisions or carry out any non-desirable activities under the guise of the corporate veil above the company, thereby misuse the privilege conferred to them, the courts are entitled to look beyond the veil, and this is known as lifting of corporate veil. But this is not a general rule and have to be applied only under exceptional circumstances. This leaves way for the instances under which the same could be done to be identified. Evolved through common law, the identified grounds are façade or sham, impropriety, single economic entity argument, evasion of taxes, avoidance of welfare legislation etc. It is worthy to note that what is important is the nature of the case. As it is an exceptional rule, the standard of scrutiny before its application is high. In conclusion, the test is whether the instances are crystal clear within statutes or whether the same are identified under the classical view or would fall within the same.

References

- Dr. G. K. Kapoor & Sanjay Dhamija, Taxmann’s Company Law: A Comprehensive Text Book on Companies Act, 2013 (21st edn., Taxmann, 2016).

- Paul L Davis & Sarah Worthington, Gower’s Principles of Modern Company Law (10th edn., Sweet and Maxwell).

- Nicholas Grier, Company Law (2nd edn., Thomson & Green).

- Sealy & Worhtington, Texts, Cases & Materials In Company Law (11th edn., Oxford).

- David Kershaw, Company Law In Context: text and Materials (Oxford).

[1] Stanley, Re, (1906) 1 Ch. 131.

[2] Salomon v. Salomon & Co. Ltd, [1896] U.K.H.L 1.

[3] Gallaghar v. Germania Brewing Company, [1893] 53 M.I.N.N. 214.

[4] Peest v. Petroldel Resources Ltd.

[5] ALAN DIGNAM & JOHN LOWRY, COMPANY LAW (6th edn., Oxford).

[6] Daimler Co. Ltd. v. Continental Tyre and Rubber Co. (Great Britain) Ltd., [1916] 2 A.C. 307.

[7] Gilford Motor Co. Ltd. v. Horne, [1933] Ch. 935.

[8] Re Bugle Press, [1961] Ch. 270.

[9] John v. Lipman, [1962] 1 W.L.R 832.

[10] Littlewoods Mail Order Stores v. IRC, [1969] 1 W.L.R 1241.

[11] Adams v. Cape Industries Plc, [1990] Ch. 433.

[12] Woolfson v. Strathclyde Regional Council, [1978] U.K.H.L 5.

[13] Cotton Corporation of India Ltd. v. G.C. Odusumath, I.L.R 1998 Kar 2553.

[14] Id.

[15] Re: R.G Films Ltd., (1953) All E.R 615.

[16] Id.

[17] Connors Bros. v. Connors, (1940) 4 All E.R 615.

[18] Subhra Mukherjee v. Bharat Coking Coal Ltd, A.I.R 2000 S.C 1203.

[19] Merchandise Transport Ltd. v. British Transport Communications, [1982] 2 QB 173.

[20] J.B Exports Ltd. v. BSES Rajadhani Power Ltd., [2007] 73 SCL 13 (Delhi).

[21] LIC v. Escorts Ltd., A.I.R 1986 S.C 1370.

[22] U.P v. Renusagar Power Co., A.I.R 1988 S.C 1737.

[23] Re. Dinshaw Maneckjee Petit, A.I.R 1927 Bom 371.

[24] The Workmen Employed in Associated Rubber Industries Ltd., Bhavnagar v. The Associated Rubber Industries Ltd., Bhavnagar, A.I.R 1986 S.C 1.

[25] Santanu Ray v. UOI, [1989] 65 Comp. Cas. 196 (Delhi).

[26] Jyoti Limited v. Kanwaljit Kaur Bhasin, [1987] 62 Comp. Cas. 626 (Delhi).

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications