This article is written by Shourya Bari, a student of JGLS.

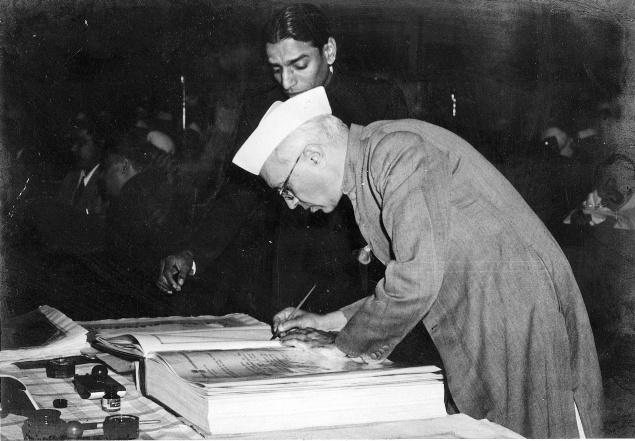

“The question now raised by the introduction of the phrase ‘due process’ is whether the judiciary should be given the additional power to question the laws made by the State on the ground that they violate certain fundamental principles…There are dangers on both sides. For myself I cannot altogether omit the possibility of a Legislature packed by party men making laws which may abrogate or violate what we regard as certain fundamental principles affecting the life and liberty of an individual. At the same time, I do not see how five or six gentlemen sitting in the Federal or Supreme Court examining laws made by the Legislature and by dint of their own individual conscience or their bias or their prejudices be trusted to determine which law is good and which law is bad…I would leave it to the House to decide in any way it likes.”- B.R. Ambedkar

The passage is perhaps one of the most historic speeches ever made by Dr. Ambedkar. The content of the speech truly captures the dilemma and dichotomy associated with the ‘due process’ clause. The phrase ‘due process’ was borrowed from the Magna Carta and means according to the law of the land. The phrase acquired procedural and substantial meaning owing the judicial craftsmanship of the Supreme Court of the United States of America. The crux of the debate revolving around the use of the phrase in India emphasizes on one crucial aspect. The presence of the ‘due process’ clause in the constitution will provide great power to the judiciary to declare laws made by the Parliament invalid. This implies a curtailment of the power of legislature to legislate on vital issues without any hindrance. The choice was simple before the members of the constituent assembly. They had to choose any one between the legislature and the judiciary to have greater power. The discourse of the constituent assembly on the issue of ‘due process’ shows that the clause was initially present in the Fundamental Rights provision associated with preventive detention and individual liberty in the initial draft version adopted by the constituent assembly in 1947. However, eventually the ‘due process’ clause was eliminated from the draft constitution. This post seeks to provide an explanation as to why the constituent assembly finally excluded the ‘due process’ clause from the constitution by referring to the proceedings of the fundamental rights sub – committee and the debates in the assembly.

Kazi Syed Karimuddin moved the amendment that the draft Article 15 should contain ‘No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty without due process of law’ in place of ‘No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law’. Mr. Karimuddin justified his move arguing that the clause ‘according to procedure established by law’ will do great injustice to the court as the duties of the court will be completed with ensuring compliance with the established procedure. Such a clause prevents a judge to interfere with any law that might be capricious or unjust. He argued in favor of providing individuals with inalienable rights in such a way, that political parties coming into power cannot snatch them away.

Shri Chimanlal Chakkubhai Shah argued in favor of retaining the due process clause in the constitution. He explains the connotation present in the ‘due process’ clause. He says that in reviewing a legislation the court will have the power to see not only that the procedure is followed but will also have the power to see that the substantive provisions of law are fair and just and not unreasonable or arbitrary. Mr. Shah counters the argument that the judiciary may not be able to fully appreciate the necessities which have required a specific legislation. He vouches in favor of the judiciary’s capacity to appreciate the necessity behind the passing of an apparent unjust or arbitrary law. Mr. K. M. Munshi staunchly supported the contentions of Mr. Shah.

Mr. Mehboob Ali Baig had pointed out that the clause ‘except according to procedure established by law’ has been borrowed from the Japanese constitution, but the drafting committee has omitted other provisions of the Japanese constitution which give meaning to the clause ‘except according to procedure established by law’. He suggests if the clause ‘except according to procedure established by law’ is read with those other provisions of the Japanese constitution it would make more sense to adapt the ‘due process’ clause.

Shri Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar put forward arguments to counter the points submitted by all the above members. Shri Ayyar first explains that the ‘due process’ clause as interpreted by the English judges connoted merely the due course of legal proceedings according to the rules and forms established for the protection of rights, and a fair trial in a court of justice according to the modes of proceeding applicable to the case. Shri Ayyar goes on to critique American judicial decisions for an inconsistent interpretation of the ‘due process’ clause on a case by case basis. Shri Ayyar explicitly expresses his skepticism towards the idea that three to four judges will enjoy the freedom to determine what constitutes ‘due process.’ He was extremely critical of the conflicting decisions rendered by the United States Supreme Court while interpreting the ‘due process’ clause.

Mr. Z. H. Lari countered the submissions of Shri Ayyar by bringing in a new point. Mr. Lari clarifies that in the United States of America no such words as ‘personal’ existed. The word liberty alone existed and possibly in that state of things, it was possible to interpret in such a way as to extend the scope of ‘due process’ of law to other spheres of life. Therefore he presents that when the word ‘personal’ has been inserted no court of law which is conscious of the requirement of the requirements of a state as well as conscious of the necessities of individual liberty will be so uncharitable to the interest of the state as to interpret it in a way to thwart the proper working of the state.

Mr. Govind Ballabh Pant was staunchly against the inclusion of the ‘due process’ clause. His vociferous opinion was that the retention of the ‘due process’ clause might mean that the future of the country was to be determined not by the collective wisdom of the representatives of the people but by the whims and vagaries of lawyers elevated to the judiciary.

Shri Ayyar was one of the members of the fundamental rights sub – committee who was initially in favor of a ‘due process’ clause. The point to note would be the reason as to why Shri Ayyar changed his stand. The change of stand by Shri Ayyar turned out to be crucial because he then became a part of the group who were against the ‘due process’ clause and formed the majority with Shri Ayyar in their group. In this context it would be wise to note the activities of constitutional adviser Shri B.N. Rau. Granville Austin in his book the Indian constitution notes that the elimination of due process was a result of B.N. Rau’s influence. In his comments on the report of the fundamental right sub – committee, he pointed out how a substantive interpretation of ‘due process’ might interfere with legislation for social purposes. Soon after that, Shri B.N. Rau began his trip to the United States, Canada, Eire and England to talk with justices, constitutionalists and statesmen about the framing of the constitution. In the United States he met Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, who told him that he considered the power of judicial review implied in the due process clause both undemocratic – because a few judges could veto legislation enacted by the representatives – and burdensome to the judiciary.

Shri B.N. Rau was influenced by Harvard Law School’s great constitutional lawyer James Bradley Thayer, who also feared that a great reliance on due process as a protection against legislative oversight or misbehavior might weaken the democratic process. In his speech Rau had pointed out that Thayer and others had drawn attention to the dangers of attempting to find in the Supreme Court – instead of in the lessons of experience – a safeguard against the mistakes of the representatives of the people. After Shri B.N. Rau returned from his trip he met Shri Ayyar a number of times and convinced him of the dangers inherent in substantive interpretation of due process. This is evident from the fact that, Shri Ayyar later became one of the most outspoken opponents of the ‘due process’ clause.

There were strong views in the assembly for and against the inclusion of the ‘due process’ clause. Dr. Ambedkar was himself in favor of the ‘due process’ clause and he was torn apart between his choice and his official duty to uphold the decision of the fundamental rights sub – committee where Shri Ayyar’s change of side turned out to be the decisive factor. It was at this point Dr. Ambedkar delivered the historic speech present in the passage. It was open to the house to decide whether ‘due process’ clause should be included in the constitution’s fundamental rights provisions.

The house decided in favor of the clause ‘except in according to procedure established by law’. Thus, in spite of passionate efforts by several members of the house the ‘due process’ clause did not become a part of the Indian constitution. This post has explained through the debates in the constituent assembly and proceedings of the fundamental rights sub – committee the decision of the house to exclude ‘due process’ clause from the Indian constitution and reasons they provided for doing so.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications

Article 21 talks about personal liberty and procedure establish by law , not article 15.

Hello,

This ‘Article 15’ is from the Draft Constitution prepared by the Constituent Assembly, not the version finally adopted.

The post uses the phrase ‘draft Article 15’. I hope, the confusion has been clarified.

Thank you.

Shourya Bari

“Due Process” words no where exists in the Constitution of India.

The exclusion of these words give firmness with which each article is emphasized in its meaning.