This article has been written by Sakshi Chahar, from Amity Law School, Noida.

Table of Contents

Abstract

In this article, we will analyse the effect of retrospective legislation that the Indian Government enacted in the form of the Finance Act 2012 to nullify the judgement of the Supreme Court in the case of Vodafone. First, we will analyse the facts of the Vodafone case to understand why the Finance Act 2012 was enacted, then how this legislation impacted the transactions of other Industry giants like Cairn Energy Plc in India. Subsequently, the two cases were taken to the International Court of Justice whose verdict penalised the Indian Government for violating the Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs). This article will also try to analyse why such legislations are against the essence of BITs and how India has been moving away from these treaties in the near past and how such a move is impacting the global image of Indian taxation regime. The article will then discuss how the major economies are trying to regulate the international taxation regime by discouraging tax havens and promoting fair and equitable business practices for the host country and companies.

Introduction

One of the many challenges that India is facing during this global pandemic is related to the domestic retrospective commercial legislation and importantly how it has impacted Industry giants like Vodafone and Cairn Energy Plc. The two cases revolve around a taxation dispute between the Indian Taxation Authority and these companies, which then converted into legal battles and went up to the International Court of Justice which however ruled against the Indian Government in both these cases. These are two landmark judgments which have not only highlighted the retrospective legislation’s contradiction with the Bilateral Investment Treaties but also raised questions on their constitutionality. In both these cases, the transactions involved Indian assets and foreign companies, the Indian Tax Authorities demanded tax to be paid in India whereas the companies claim that the Indian Tax Authorities do not have the jurisdiction because their companies are not incorporated in India. These cases also highlight how companies, through their web of subsidiaries in Tax Haven countries, are able to tactfully plan avoidance of taxation liability and at the same time be in accordance with the law of the land in which they operate and how that costs the host country. To understand the two judgements, we would first need to understand the background of the cases.

The Vodafone saga

Rs. 22,000 Crore (2.126 Billion UK Pound) is the amount that the Vodafone and Indian Government have been arguing for since 2007. The case began with the Telecom Communication Company called Hutchison Telecom International Limited, Hong Kong (HTIL), which had telecom operations in India, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. These operations weren’t dealt with directly, rather they had various subsidiaries that they operated through, one such subsidiary was CGP Investments Holding Limited (incorporated in the Cayman Islands) (100% or wholly owned subsidiary of HTIL). It invested in a number of telecom companies, including the telecom giant in India, Hutchison Essar Limited (herein referred to as ‘Hutch’)

After the investment, CGP Investments owned 67% of the stakes in Hutch along with the Essar Group which owned 33%. In the year 2007, the telecom giant Vodafone International Holdings BV, Netherlands bought from the CGP Investments 67% of the stake for Rs. 60,000 Crore ($ 11.1 Billion) and formed Vodafone Essar. This huge sum was paid to HTIL without Vodafone paying any tax to the Income Tax Authority in India.

The Tax Authority objected and demanded tax to be paid, whereas Vodafone refused to pay the same. Vodafone has reasoned that this Sale Purchase Transaction was between Vodafone, a Dutch based company and HTIL, a Cayman Island based company, therefore they claimed that capital gain does not arise in India and they are not liable to pay any tax to the Indian Authority. Indian Tax Authorities claimed that Hutchison has not sold the shares of CGP, which they claimed to be a shell company, but what they have sold are the Management & Controlling Rights of Hutch Essar in India, therefore capital gain is taxable in India. To counter the claims of the Indian Tax Authority, Vodafone took the matter to the Bombay High Court, where the Court had observed that all gains and money that Hutchinson has made was due to using Indian Assets and it was also observed that CGP is a shell company and what was actually sold by the company are the Controlling & Management Rights of Hutch so the capital gain will arise in India and they are obliged to pay tax in such a transaction.

Vodafone refused to stand by the verdict of the Bombay High Court and took the matter to the Supreme Court, where the court had to look carefully if what Vodafone was doing can be termed as Tax Evasion (If what Vodafone was doing was to manipulate their way out of the taxes) or Tactful Tax Planning (If it was prudent way of tax planning without ill intention). The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Vodafone stating that what is sold are the shares of a Foreign Company and Indian Tax Authority has no jurisdiction in things that are happening outside India and declared what Vodafone was doing as Tactful Tax Planning.

The Govt. of India in retaliation, then introduced the Finance Act 2012 to nullify the judgement of the Supreme Court, in a way to get Vodafone to pay those taxes, by what is known as Retrospective Legislation.

The various provisions in the Act which are prominently applicable in the present case are thatL

- First, the Definition of Capital Gains stated that if Management and Controlling Rights are present in India, then they will be considered as Capital Assets as well,

- Second, the Definition of Transfer stated that if the Controlling and Management Rights are being transferred outside of India in any way, it will be treated as a transfer as well,

- Third, Section 9(1) expressly states that, if Assets located in India are being sold then Capital Gain will arise in India. The Government added Explanation 5 through Finance Act 2021 stating that the shares of a foreign company will be deemed to be located in India if they are deriving their value substantial from assets located in India,

- forth, The Act also threw light on the meaning of the term ‘Derive its value Substantially’ – if, on a specified date, the value of such assets – 1) exceeds Rs. 10 Crore and 2) represents at least 50% of the value of all the assets owned by the company.

In short, the Finance Act 2012 asserts that CGP is a foreign company but it’s shares will be deemed to be located in India because shares of CGP derive their value substantially from assets located in India. So now, if CGP’s shares are being sold, Capital Gain will be applicable in India. A clarification was then sought from the board, that if CGP pays dividend to HTIL and since its shares are deriving its substantial value from assets situated in India, will the dividend also be taxed in India? The Board clarified that these amendments are for a limited purpose of transfer of shares and therefore if CGP is paying dividend to HTIL, it will be considered as dividend by a foreign company, hence it will not be taxed in India.

The lawmakers further added explanation in Section 9, that if shareholders who have shares up to 5% of such companies and those who do not have right to transfer Controlling and Management Rights, sell their shares outside India then explanation 5 will not be applicable in such cases.

The Govt has extended the applicability of the Finance Act, 2012 to 1962, which means that if anyone had violated that part of the law made by the amendment from the year 1962, would be prosecuted.

In retaliation to the retrospective change of taxation law, Vodafone PlC had invoked India-Netherlands bilateral investment treaty in 2013, seeking a resolution to the tax demand imposed on it by enacting a tax law with retrospective effect to sidestep a Supreme Court judgement that went in the company’s favor. Vodafone had argued that India did not have jurisdiction over the matter on account of its investment pact with the UK. It moved the International Court of Justice in 2016 and the Indian government stated that it was an “abuse of the process of law”. In September 2020, an international arbitration tribunal called the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague had ruled the imposition of tax liability on Vodafone violated the investment treaty agreement between India and the Netherlands.

The Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) further rules that the Government of India has to pay back Rs. 45 Crore (4.35 Million UK Pounds) they had taken from Vodafone and reimburse 40 Crore (3.8 Million UK Pounds) in Legal Fees that Vodafone had to pay in fighting this legal battle.

The Indian Govt now had two options:

- Either appeal in the Appeals Court, or

- They could also contest that a tax matter in India can’t be decided in the International Court of Justice and can choose to ignore the verdict of the International Court of Justice entirely.

But if they choose to do the latter, India would lose its credibility as a place where foreign investors can conduct smooth business. The verdict given by the Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), that ruled India’s demand of Rs 22,100 Crore in taxes from Vodafone using retrospective legislation was in “breach of the guarantee of fair and equitable treatment”, was challenged by India before the Singapore office of PCA.

This was decided two days after India had lost yet another arbitration case that dealt with a tax dispute with the UK Oil major Cairn Energy Plc. The PCA in its verdict asked India to pay Rs 8,000 crore (773 Million UK Pounds) as damages to Cairn.

Another hit by the same legislation

Cairn is a leading independent oil and gas exploration and development company majorly operating in Europe. Cairn Energy has been investing in India since the 1990s and also became one of the first multinational companies to participate in India’s oil and gas exploration and then also discovered the Mangala oil field in Rajasthan in January 2004. It was one of the biggest hydrocarbon discoveries in India and was then followed by additional Bhagyam and Aishwarya oil discoveries in the nearby localities.

The present case revolves around capital gains tax on a restructured company (Cairn India) that was sold close to a decade ago.

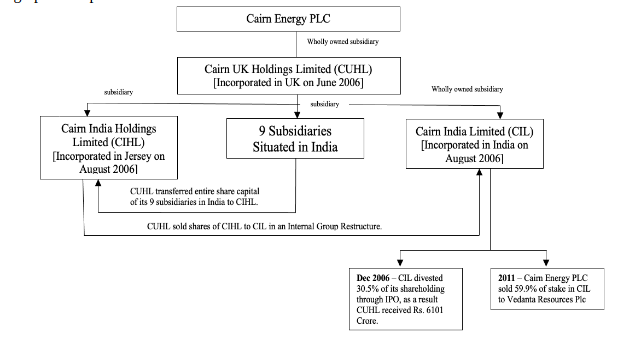

Cairn UK Holdings Limited (CUHL), a United Kingdom based company which was incorporated in June, 2006 as a subsidiary of Cairns Energy PLC, United Kingdom. After that, another company named Cairn India Holdings Limited (CIHL) was incorporated in Jersey, US in August 2006 as a wholly owned subsidiary of CUHL. After signing a share exchange agreement between CUHL and CIHL, the former transferred shares of all of its nine subsidiaries, that were engaged in India in the oil and gas sector, to the latter which resulted in transferring shares of non-Indian companies to an Indian holding company.

Later in August 2006, a company was incorporated in India called Cairn India Limited (CIL) as a 100% subsidiary of CUHL. Then in October 2006, to give effect to an internal group restructuring which was essentially the main transaction on which the tax dispute arose, CUHL (UK based) sold shares of CIHL (Jersey based), which now had all the shares of the nine subsidiaries engaged in the oil and gas sector in India, to CIL. This came into effect by way of a share purchase deed and subscription and share purchase agreement, which resulted in transfer of the entire share capital of CIHL to CIL. The consideration paid for the transfer was partially in cash and partially in the form of shares of CIL. Then, in December 2006 CIL divested 30.5% of its shareholding by way of an Initial Public Offering in. As a result of such divestment, CUHL received Approx. INR 6101 Crore (approx. US $ 931 million).

Then in 2011, Cairn Energy PLC, United Kingdom, which was the parent company, sold 59.9% of all its shareholdings in CIL to Vedanta Resources Plc owned by Anil Aggarwal and incorporated in the UK. However, CUHL was not allowed to transfer its 9.8 per cent stake in CIL to Vedanta.

A graphical representation of the entire transaction is as follows:

In January 2014, several years after the transaction had taken place as per the existing law, the Taxation Authority of India initiated reassessment proceedings which takes place in cases where income has escaped assessment. The Tax Authorities then issued the assessment as a draft stating Rs. 24,500 Crore (Approx. USD 3.742 Billion) as short-term capital gains which will be chargeable to tax at a 40% rate. CUHL then made an appeal before the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal (ITAT), Delhi bench against such a claim.

At the ITAT, CUHL argued that it should be assessed as per Section 9 of the Income Tax Act as it was before enactment of the Finance Act, 2012 by way of retrospective legislation. The case pertains to the transaction which effected an internal reorganisation of the Cairn group without any involvement of a sale or transfer to a third party, it does not change any controlling interest and that no tax should be levied on the transaction which has not resulted in increase of wealth or income of the group.

The Tax Authority then argued that any income accruing or arising to CUHL, being a non-resident, directly or indirectly, by the transfer of a capital asset placed in India, it shall be deemed to accrue or arise in India. Since the shares of CIHL derive their substantial value from assets in India, they are deemed to be situated in India.

The tax department then also attempted to distinguish this case from the Vodafone case on the ground that in the latter, it was a transfer of a foreign share between two non-residents while in the former, it was a transfer from a non-resident to a resident and hence the latter could not be applied.

On 10 March 2015, Cairn Energy had then initiated international arbitration proceedings at the Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), under the India-UK BIT against the aforesaid measures adopted by the Indian government. In December 2020, a three-member international arbitral tribunal had ruled in a unanimous verdict that the Indian government was “in breach of the guarantee of fair and equitable treatment” which was against the India-UK bilateral treaty and that the breach caused a loss to the British energy company. It awarded Cairn $1.2 billion in compensation that India was liable to pay. To enforce this award, Cairn moved a court in the South District of New York against Air India, the National Air Carrier of India. Cairn chose Air India because it is a Government run company and has a substantial amount of assets in New York. Meanwhile, India has also challenged the arbitration award in at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), Netherlands.

Are such legislations contrary to the bilateral investment treaties?

Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) are known as the agreements between two countries for the mutual protection & promotion of investments in each other’s territories by individuals and companies situated in either country. The following are the essential clauses covered under BITs:

- Applicability,

- Fair and Equitable Treatment and Full Protection & Security,

- National treatment and Most-favoured-nation treatment,

- Expropriation,

- Dispute settlement mechanisms, both between States and between an investor and State.

BITs main objective is to encourage foreign investors to invest in a state and then also contribute towards the overall developments and advancements of the country’s economy.

The clause of ‘fair and equitable treatment’ guarantees that the company or individual will be provided a stable and predictable legal framework, also following due process while modifying the legal framework which might potentially impact the investors, also abiding principles of transparency and non-arbitrariness, among others.

It is pertinent to mention here that the Vodafone & Cairn cases have not arisen out of an investment contract between these companies and the Government of India. These disputes have emanated from retrospective tax legislation by India, which was brought under an International Investment Agreement (IIA). While these companies could have exercised a right to challenge the constitutionality of the amendment before the Supreme Court of India, they chose to initiate arbitration under the BIT.

Both Vodafone and Cairn have invoked ‘fair and equitable treatment’ clauses to safeguard their interest against the Retrospective Legislation which contradicts the requirement to provide ‘stable and predictable legal framework to foreign investors’.

India has entered into new bilateral investment treaties such as the 2018 India Belarus BIT and the 2020 India Brazil BIT but they have mostly excluded measures regarding enforcement of taxation obligations from their scope. Going forward, it is likely that India will fiercely negotiate on incorporation of such exclusions in bilateral investment treaties.

Retrospective legislation – the root cause of the problem

Is the retrospective legislation unique to India only? The answer to this is in the negative, countries like USA, Australia, UK have also resorted to retrospective legislation when needed. For example, in Australia, it is a common practice to change the law retrospective whenever required. UK Governments had traditionally used retrospective tax rules to either fix perceived gaps in existing rules to ensure that they operate as originally intended or as a means of preventing widespread proliferation of tax. In the US, the legislation does have the power to pass retroactive law, yet not all states have empowered their legislators to do so. Several state constitutions, such as those of Georgia and Texas, flatly prohibit the legislature from enacting any law with retroactive application, including tax laws.

Why India should refrain from using Retrospective Legislature is because we still need other nations to come and set up their business practices here in India, to boost FDI, employment and also boost our Ease of Doing Business Ratings in the Global Markets, where one of the aspects is Paying Tax. Where the other nations (like USA, UK) are performing better at other aspects of such Rankings (such as Enforcing Contracts, Construction Permission etc.), India still has a long way to go to climb up the ladder of such Ratings.

Though India may have climbed from Rank 142 in 2014 to 63 in 2020 in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index, the future does not look very bright. It has been noticed through the latest Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) (2016, 2018 and then 2020) that India has been moving away from an investor-friendly approach to a protective approach which has been severely criticized. Between 2016-2019, India terminated around 60 BITs, sending a negative message to investors. Since 2016, only 4 BITs have been signed by India, out of which none are in force yet.

Recent developments in the International Taxation Laws

Advanced economies which make up the G7 have recently reached a “historic” deal on taxing multinational companies. The respective Finance Ministers of the said countries agreed to counter tax avoidance through measures to make companies pay in the countries where they do business. The deal announced on 5th June 2021 involving the US, the UK, Germany, France, Canada, Italy and Japan, is likely to be put before a G20 meeting in July 2021.24 The following main decisions were taken:

- First, it has been ratified to force multinationals to pay taxes where they operate.

- Second, it commits states to a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15% to avoid countries undercutting each other.

The accord, which could form the basis of a global pact in July 2021, is aimed at ending a decades-long “race to the bottom” in which countries have competed to attract corporate giants with ultra-low tax rates and exemptions.

This accord is targeted at the companies which typically rely on complex webs of subsidiaries to hoover profits out of major markets into low-tax countries such as Cayman Island Mauritius, Hong Kong, Panama, Ireland or Caribbean nations such as the British Virgin Islands or the Bahamas.

The US Treasury loses nearly $50 billion a year to tax cheats, according to the Tax Justice Network report, with Germany and France also among the top losers. India’s annual tax loss due to corporate tax abuse is estimated at over $10 billion, according to the report.

Conclusion

After extensive deliberations of both the cases of Vodafone and Cairn, the common thread in both the cases are the web of subsidiaries that were created to avoid the payment of taxes by tactfully planning and still appearing to be in compliance with the law of the land that they operate. As discussed in the recently held G7 meeting, the countries, where such companies are operating, are losing lots of revenue in form of taxation from these companies. The countries should not resort to Retrospective Legislation as it is not just arbitrary but also not in compliance with the ‘fair and equitable treatment’ clause in the Bilateral Investment Treaty, it creates an environment of uncertainty for foreign investors and discourages such investments in the country. However, as each country has the right to protect its interest and claim in the form of taxes from the companies that are operating in their land, they should take note of such loopholes in their laws and policies and make prospective changes to save their interest and be fair to such investors as well.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals, and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications