This article is written by Puru Rohatgi, Student, School of Law, Christ University, Bangalore.

Introduction

The United Nations was formed by numerous diplomats in 1945. When they met to form the UN, setting up of a global health organization was one of the main things that they discussed. World Health Organization’s (WHO) constitution was formed soon and it came into effect on 7th April 1948. The IHR (International Health Regulations) 2005, is an agreement between all the countries to work collectively for global health security. It consists of rights and obligations for these countries in agreement regarding surveillance, assessment, public health response, health measures and many more subjects. A proper legal framework to support all the IHR policies is required in every country.

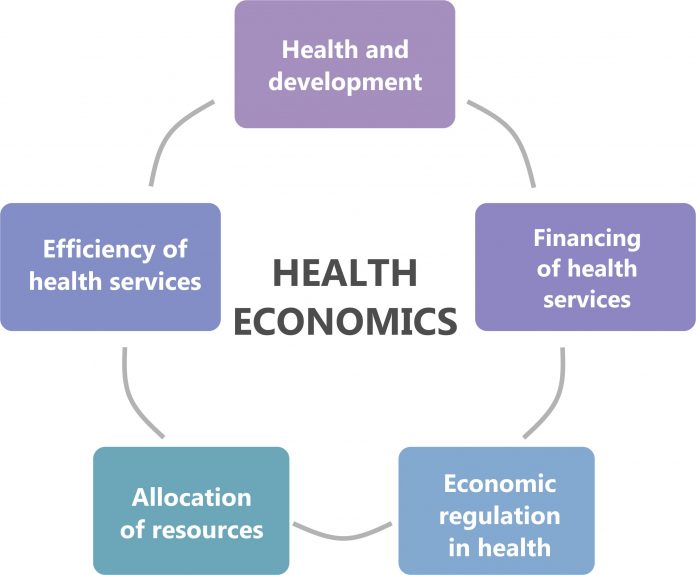

Health economics explains the relationship between health and the resources that are needed to promote it. These resources are both monetary and non-monetary in nature. The issue that arises in this context is that how does the law regulate the optimum utilization of these finite resources for the infinite needs of humans?

Health economics in Development conveys two meanings: that the science of health economics itself has been developing during the period covered, and continues to do so; and that the application of health economics contributes to development, broadly defined, both by improving health and by reducing the waste of resources devoted to health care. As to the first, health economics is a relatively young sub-discipline, roughly 40 years old and expanding rapidly. In 1982, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) sought to hire an economist with 10 years’ experience in health issues in Latin America. That was a novel departure for PAHO, and it was resisted by a number of staff members trained in public health and deeply suspicious of economists and their ways of thinking. Moreover, there was probably no one alive who could meet the job requirements then. By the end of the century, the situation was quite different: PAHO not only employed several economists but promoted and published studies of the relations between health and development. This change of attitude reflects the growing realization that economic thinking is not inimical to the ethical concerns of health professionals, and that the expansion of health economics as a field of inquiry has made it steadily more relevant and more useful to health organizations. As to the second, there is increasing evidence that improvements in health, far from being a pure consumption good or even a luxury, often represent valuable investments in people’s capacities to learn and to work, and are sometimes essential to rescue people from poverty or prevent their impoverishment.

Why healthcare professionals need to know about health economics?

When a physician is actually practicing medicine there seems to be no room or need for economic understanding. In fact, it might get in the way, when what the doctor wants is to concentrate on the patient before him or her and bring to bear all his or her medical knowledge, which is typically much more detailed – and certainly more important at the moment of diagnosis or treatment – than what an economist typically knows or thinks about. And doctors have been treating patients, well or badly, for centuries without troubling themselves with economic concerns.

Economics perhaps has no place in the surgery, the consulting room or the laboratory, but that is not what matters. In each of those settings, resources are being used and a production process is underway, supposedly for the benefit of a consumer – and the use of limited resources to produce goods and services for intermediate or ultimate consumers is what economics is primarily about. How those resources are themselves produced, how they are combined, who choose what to produce with them, who will pay for them, and what all that costs, create the setting in which the physician operates. Almost everything that happens prior to the encounter between the health care professional and the patient is relevant to the economist, even if the latter is kept outside of the medical practice itself. Is there is something the health care professional ought to know of health economics, it concerns those prior steps, including many of the factors that bring the patient to his or her attention in the first place.

There are at least three reasons why a health care professional might disregard this argument and suppose that economics has nothing useful to offer his or her profession. One is the fact that health economics is a relatively new sub-discipline. Today health economics has become steadily more important as more and more of health care is financed by insurance and the costs of it have risen. Economists are quick to “invade” fields they find interesting, and the practitioners of those subjects may take time to notice that they have become of economic interest.

A second reason is a mistaken supposition that economics is nothing more than accounting, and while accounts must be kept in medical practice as in other professions, the logic of the accounting is no different and the accountant has no special insights to offer. Much of economics does, in fact, depend on proper accounting: the creation of national accounts of income and product, starting more than a half-century ago, is the precursor of today’s effort to create national health accounts to show where the funds spent on health come from and where they go. But the interpretation of those flows doesn’t follow only from their magnitude, but from economic theory about how doctors, patients, and financial agencies behave.

A third, even more mistaken reason, is summarized in the attitude that “health is not a business”, or should not be one. Some doctors, and public health professionals in particular, often find it hard to accept that health care is financed, produced and delivered in a constellation of markets – as though markets or “business” were intrinsically inimical to human health. This argument usually rests on the claim that health care is a basic right or a basic need, and therefore too important to be left to markets. But food, which is a much more basic necessity than health care, is produced and delivered in markets, and there is nothing wrong with that. The question in the case of health care, is whether those markets work in socially desirable ways or whether they lead to situations in which some people cannot afford needed care, or the wrong kinds of care is produced, or at too high cost, or something else goes wrong. Economics is, to a large extent, the science of how markets operate, so it is extremely relevant to markets in which failure may be a matter of life and death.

Why public role in healthcare matters?

Health care in about 1990 cost at least 1.7 trillion dollars, or about 8% of world income, making it one of the largest industries in the global economy. On average, 60% of this is public spending. If this spending is excessive or otherwise inappropriate, the consequences for the economy and for health outcomes could be substantial. Governments also provide a large share of health services, sometimes as large as the share in spending, and often intervene in various ways in the private health care market. Since most health care is a private good, it is surprising that so much of it is provided, financed or regulated by the state. In contrast to what happens in many other sectors of the economy, this substantial public role is most pronounced in high-income countries which are generally very market-oriented; the state usually finances a smaller share of health care in poorer countries. Besides consuming large resources, many health systems are regarded as inefficient or inequitable or both; they are often described as in “crisis” as needing reform, or as having failed. If the supposed failures of health systems are real, they might be caused by misguided public intervention so they could be corrected by a smaller or different public role and a greater reliance on private markets. Or governments might intervene for sound reasons, to correct or compensate for failings in those markets; that is outcomes would be even worse if left entirely to the private sector. It is relatively simpler to conclude that governments should do certain things and should leave others to private activity, but often there is a variety of possible solutions and no obviously best approach. Theory doesn’t always provide clear answers, and the empirical evidence is incomplete, extremely varied and difficult to interpret.

Economic analysis of World Health Organization’s policies

The policies laid down by the WHO represent a serious impending issue that must be addressed in the present in order to avoid irreversible and adverse economic consequences. The economic aspects associated with World Health Organization and its policies are:

- Information Asymmetry in the Public Sector- Asymmetric information is a situation in which a buyer and a seller possess different information about a transaction or exchange. There are three major ways in which information asymmetry can occur – between doctor (health care professional) and health care system (administrator); between patient and health care system; and between patient (public) and doctor. In the first case, doctors have a better understanding of legitimate demands, while administrators have an understanding about supply and cost of available resources but know little about a chosen intervention’s effectiveness. In the second case, patients try to avoid the high costs of paying health care premium. Similarly, there is often a lack of information and understanding of available public programs. In economic terms, the benefit of gathering useful information about such programs is generally undervalued compared with its cost. Lastly, patients know more about their health and the symptoms than the doctor, but they may not express it properly – be it reluctantly or intentionally. On the other hand, doctors know more about the cases and effects of available treatments but may not be able to communicate them properly to the patient. Such issues are normally worse in the public sector, where patients are generally poor and uneducated. Not just in health care centers set up by WHO, even in terms of the implementation of the new policies and frameworks of WHO, there exists information gap. This is quite evident as the WHO are more aware of their policies than the public at large.

- Associated Higher Transaction Costs- Such information asymmetries add to agency costs in terms of monitoring, structuring and bonding contracts among agents and principals with rebelling interests. There are two aspects to this. Private firms’ motive is to increase their profits, so their expenditure on agency costs is limited. But on the other hand, public agencies do not receive clear signals about the agency cost of such information asymmetry because of unspecified social functions and complex sources of subsidies. Unsurprisingly, many public health care facilities do not maintain clear and detailed patient records. Doctors maintain an information advantage that puts them on a higher pedestal to pursue their own interests. As a whole, in such area of information asymmetry, the expenses of WHO increase on both useful and unnecessary things. This explains the concept of transaction cost in the implementation of policies by the organization too.

- Abuses of Public Monopoly Power- In addition to the above accountability and information problems, when the public health care centres (set up by the WHO in around 150 countries with more than 7000 employees) enjoys a monopoly, people who work for it are given a wide scope of abusing this power – extraction of rents and lowering of quality. Often monopoly suppliers reduce output and quality while raising prices. This leads to inefficiency or a net deadweight welfare loss to consumers who have sacrifice the intake of other goods. Also, monopoly suppliers have strong incentives to lower expenditure through decreased output. The executives at these public centres often receive huge social benefits and other perks. All these monopoly issues lead to a failure of critical policy formulation.

- Failure of Critical Policy Formulation- The market often does not lead to welfare-enhancing production and allocation of a number of health care goods and services. These include public goods (policymaking and information), goods with large externalities (disease prevention) and goods with stubborn market failure (insurance). While the WHO is busy producing healing services, the above three areas are frequently neglected. Also, when most funds are spent on poor public productions, lesser or no resources are left for strategic purchasing of services for the poor.

- Cost and benefit analysis- It is the aim of every organization to increase their profits while reducing costs. Awareness of the cost effects of health results and understanding of cost behaviour is serious at all levels of health care. ‘Cost’ is the value of resources used to produce something. Financial cost is the measure of loss in the monetary form when something is consumed. It represents how much money was paid for the provision of service, in our case by the WHO. Economic cost, on the other hand, expresses the full cost accepted by society and are grounded on the opportunity cost. Economic costs must include the prices of all the goods and services that are provided for free by donors or volunteers and also those that are subsidized. While examining the cost-benefit analysis for WHO, the cost of implementing the policies should be equal to the benefit derived from the customers.

Conclusion

Health policy responds to many factors, some of them political and some quite ideological, in addition to the economic circumstances that constitute a crisis or the adjustment to one. That alone makes it difficult for health policy to change quickly and sensibly if a crisis arises.

The World Health Organization aims for a disease-free economy all over the world. Amongst the 150 countries, where it has set its health care centres, most of them are developing economies. Here, it is analyzed how information asymmetry and other economic aspects are directly or indirectly connected with the legal policy frameworks of WHO with respect to the legally binding instrument of international law, the International Health Regulations of 2005. The IHR doesn’t just assist the countries to work collectively in the interest of the livelihoods of disease-prone people, it also avoids the needless interference with international trade and travel.

IHR essentially plays a dominant role in providing a legal framework to the World Health Organization’s policies, as to whether they are being efficiently implemented or not. From this analysis, we can infer the significance of economics in the contemporary world.

References

- Principles of Health Economics For Developing Countries by Willian Jack

- Stephanie Wels’ article on “What Is Health Economics?” (https://www.jhsph.edu/departments/international-health/global-health-masters-degrees/master-of-health-science-in-health-economics/what-is-health-economics.html)

- International Health Regulations (IHR) (Legal) (http://www.who.int/ihr/elibrary/legal/en/)

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Click Here

Click Here

Allow notifications

Allow notifications

Thanks sharing this informative post.