This article is written by Akash Deep Bandhe pursuing Certificate Course in Advanced Criminal Litigation and Trial Advocacy from LawSikho.com.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Concept of rights

“To deny people their human rights is to challenge their very humanity”, Nelson Mandela. Human beings by the quality of being human, enjoy certain inalienable rights which are known as human rights. As these rights are held by them because of their very being, they become operational since their birth. These rights being the birthright, are hence, intrinsic in all the persons regardless of their caste, creed, religion, sex and nationality.

These rights are indispensable for all individuals as they are consistent with their freedom and dignity and are instrumental to physical, moral, social and spiritual well-being. They are also essential as they offer appropriate conditions for the material and moral upliftment of the individuals. Since their vast significance to human beings; human rights are also on occasion referred to as fundamental rights, natural rights and birthrights.

The notion of these rights emerged from the want to guard the individuals against the use of unjustified state power. Care was hence primarily focused on rights that compels the State to forbid certain actions. Human rights in this category are commonly referred to as fundamental freedoms. Since human rights are regarded as a prerequisite for leading a dignified human existence, they work as a guide and standard for legislation.

Definition of human rights

The term “human rights” signifies the class of rights, which are intrinsic in our nature and without which we cannot live as human beings. Human rights being an imperishable section of the nature of human beings are important for people to advance their personality, their human qualities, intelligence, and conscience and to fulfil their spiritual and other higher requirements. Moreover, it is expressed that the rights which are natural and intrinsic for life and happiness of every person and thus this right are known as human rights. These rights are indispensable for the welfare of human dignity and the individual. Man as a part of the community has some rights in order to him endure, sustain and nourish his possibilities.

The Magna Carta (1215)

Magna Carta, or “Great Charter,” penned in 1215 by the King of England, was a critical point in the progression of human rights. In 1215, after King John of England infringed a number of olden laws and customs by which England had been ruled, his subjects compelled him to sign the Magna Carta, which set forth what later came to be known as human rights. Amongst them was the right of the church to be free from sovereign intervention, the rights of all free citizens to own and inherit assets and to be shielded from disproportionate taxes. It recognized the right of widows who possessed property to choose not to marry again and recognized the principles of due process and equality before the law. It also had provisions forbidding bribery and official transgression. Commonly considered as one of the most significant legal documents in the development of modern democracy, the Magna Carta was a critical turning point in the fight to establish freedom and liberty.

In 1776, rebellious American colonists saw the Magna Carta as an example for their demands of liberty from the English monarchy. Its legacy is particularly apparent in the Bill of Rights and the U.S. Constitution, and nowhere more so than in the 5th Amendment which states that “Nor shall any persons be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law”. Further, many state constitutions also contain ideas and phrases that can be linked directly to this significant document.

Human Rights and Constitution of India

The concept of human rights can be traced to the natural law Philosophers such as Locke and Rousseau. The natural law philosophers philosophized over such inherent human rights and sought to preserve these rights by propounding the theory of social contract. According to Locke, man is born ‘with a title to perfect freedom and an uncontrolled enjoyment of all the rights and privileges of the law of nature’ and he has by nature a power ‘to preserve his property-that is, his life, liberty and estate, against the injuries and attempts of other men.’

The concept of fundamental rights represents a trend in modern democratic thinking. The enforcement of human rights is a matter of major significance to modern constitutional jurisprudence. The incorporation of fundamental rights as enforceable rights in the modern constitutional documents, as well as the internationally recognized charter of human rights, emanating from the doctrine of natural law and natural rights.

While interpreting the fundamental rights in the Indian Constitution, the Supreme Court has drawn from the International Declaration of Human Rights. In the case of Chairman Railway Board v. Chandrima Das, the Supreme Court has made copious references to the UDHR, 1948, and observed: “The applicability of UDHR and principles there may have to be read, if need be, into the domestic jurisprudence.”

Specific Rights under the Constitution

Article 13: Laws inconsistent with or in derogation of the fundamental rights

Article 13 is a protective provision and an index of the importance and preference that the framers of the Constitution gave Part III of the Constitution. Article 13 of the Constitution not only declares the pre-constitution laws as void that they are inconsistent with the fundamental rights but also prohibits the State from making a law that either takes away totally or abrogates in part a fundamental right. The effect of Article 13 is that fundamental rights cannot be infringed by the government either by enacting a law or through administrative action.

In the Indian democracy, neither administration of justice nor functioning of the Courts can be rendered irrelevant by actions of the other organs of the state. Article 13 of the Constitution prescribes that if relevant laws are inconsistent with Part III of the Constitution when enacted, they shall thereafter be held to be void to the extent of such inconsistency. The power of the legislature, thus, is limited by the very fundamental restriction prescribing that it cannot enact laws inconsistent with the fundamental rights of the citizens.’

Article 14: Equality before law

A constitution bench of the Supreme Court has declared in no uncertain terms that equality is a basic feature of the constitution and although the emphasis in the earlier decisions revolved around discrimination and classification, the contents of Article 14 got expanded conceptually and has recognized the principles to comprehend the doctrine of promissory estoppel non-arbitrariness, compliance with the rules of natural justice eschewing irrationality etc.

The underlying purpose of Article 14 is to treat all persons similarly circumstanced alike, both its privileges conferred and liabilities imposed. Classification must not be arbitrary but must be rational, that is to say, it must not only be based on some qualities or characteristics which are found in all persons grouped together and not in others who are left out but those qualities and characteristics must have a reasonable relation to the object of the legislation.

Article 19: Protection of certain rights regarding freedom of speech, etc

Article 19 of the Constitution guarantees six fundamental rights to the citizens of India which, subject to specified limitations, they can exercise throughout the territory of India. These are the right to; freedom of speech and expression, assembly, association, movement, residence and settlement, and profession, occupation, trade or business.

The rights enumerated in Article 19(1) are those great and basic rights and liberties that are recognized as the natural rights inherent in the status of a citizen and are preconditions for a democratic state based on the rule of law. None of these rights is, however, absolute or uncontrolled and each one of them is liable to be abridged by existing and future laws to the extent mentioned in clauses (2) to (6) of that article. Clauses (2) to (6) recognize the power of the State to make laws imposing reasonable restrictions for reasons or grounds set out in them. The difference in the contents of clauses (2) to (6) also indicates that the rights in clause (1) “do not stand on a common pedestal but have varying dimensions and underlying philosophies” as held in the case of Dharam Dutt & Ors vs. Union Of India & Ors.

The principle on which the power of the State to impose restriction is based upon that, all individual rights of a person are held subject to such reasonable limitations and regulations as may be necessary or expedient for the protection of rights of others, generally expresses as the social or public interest.

Article 20: Protection in respect of conviction for offences

The three clauses of this article deal respectively with – ex post facto laws, double jeopardy, and prohibition against self-discrimination.

Ex Post Facto Laws

The rights secured by clause (1) corresponds to the provisions against ex post facto laws of the US Constitution which declares that no ex post facto laws be passed. Broadly speaking ex post facto laws are laws that punish for what was lawful when done. That is, an act that was lawful when done cannot be declared or made an offence by a law made after the commission of the act. The law can make such acts an offence only for the future. “There can be no doubt”, said Jagannath Das J in the case of Rao Shiv Bahadur Singh And Another vs. The State Of Vindhya Pradesh, “as to the paramount importance of the principle that such ex post facto laws which retrospectively create offences and punish them are bad as being highly inequitable and unjust.”

Double Jeopardy

The right secured under clause (2) is grounded on the common law maxim nemo debet bis vexari – a man should not be brought into danger for one and the same offence more than once. If a person is charged again for the same offence, he can plead, as a complete defence, his former acquittal or conviction, or as it is technically expressed, take the plea of autrefois acquit or autrefois convict.

The corresponding provision in the US Constitution is embodied in the 5th Amendment which declares that no person shall be subject to the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb. The principle has been recognized in the existing law in India and is enacted in Section 26, General Clauses Act, 1897, and Section 300 CrPC.

Although these were the materials that formed the background of the fundamental rights given in Article 20 (2) of the Constitution, the ambit and content of guarantee are much narrower than those of the common law in England or the doctrine of “double jeopardy” in the US Constitution or Section 300 (old section 403) of CrPC.

Prohibition against self-incrimination

Clause (3) of Article 20 declares that no person accused of an offence shall be compelled to be a witness against himself. This provision embodies the principle of protection against the compulsion of self-incrimination which is one of the fundamental canons of the British system of criminal jurisprudence and has been adopted by the US system and incorporated in the US Constitution. The 5th Amendment of the US Constitution provides that no person shall be compelled in any case to be a witness against himself. It has also, to a substantial extent, been recognized in the criminal administration of justice in this country by incorporation into various statutory provisions. The Constitution of India raises the rule against self-incrimination to the status of the constitutional prohibition. The Supreme Court has given a refreshing analysis of Article 20 (3) in the context of national and international developments in Human Rights in the case of Selvi vs. State of Karnataka.

Article 21: Protection of life and personal liberty

Article 21, even though couched in negative language, confers on every person the fundamental rights to life and personal liberty and has become an inexhaustible source of many rights. These rights are as much available to non-citizens as to citizens and to those whose citizenship is unknown and our courts assign them a paramount position among the rights.

Life – the right to life that is the most fundamental of all is also the most difficult to define. Certainly, it cannot be confined to a guarantee against the taking away of life; it must have a wider application. With reference to a corresponding provision in the 5th and 14th Amendments of the US Constitution, which says that no person shall be deprived of his “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”, in Munn v. Illinois, Field J, spoke of the right to life in the following words;

“By the term “life”, as used here, something more is meant than mere animal existence. The inhibition against its deprivation extends to all those limbs and faculties by which life is enjoyed. The provision equally prohibits the mutilation of the body by the amputation of an arm or leg, or the putting out of an eye, or the destruction of any other organ of the body through which the soul communicates with the outer world.”

Personal liberty – the expression “liberty” in the 5th and 14th Amendments to the US Constitution is given a very wide meaning. It takes in all the freedoms that a human being is expected to have. The expression is not confined to mere freedom from bodily restraint, and “liberty” under law, but extends to the full range of conduct which the individual is free to pursue. In contrast to the US Constitution, Article 21 qualifies “liberty” by “personal”, which leads to an inference that the scope of liberty under our Constitution is narrower than in the US Constitution. Seemingly that was the impression drawn by some of the judges in A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras. Though that case was concerned about the constitutionality of preventive detention of the petitioner which in any case was an infringement of the “personal liberty” even in the narrowest sense of the term and therefore it may be said that the scope of “personal liberty” was not an issue in that case, yet some English jurists concluded that “personal liberty” was confined to freedom from detention or physical restraint. But there was no definite pronouncement made on this point since the question before the court was not so much the interpretation of the words “personal liberty” as the interrelation between Article 19 and 21.

Article 22: Protection against arrest and detention in certain cases

Article 22 was initially taken to be the only safeguard against the legislature in respect of laws relating to deprivation of life and liberty protected by Article 21. That position, as we have seen in our discussion on Article 21, has been changed since Maneka Gandhi v. UOI. Now Article 21 has become a source of restraint upon the legislature. Consequently, the relationship between Articles 21 and 22 has not only changed drastically but rather reversed. Earlier “the procedure established by law” for depriving a person of his life or liberty under Article 21 drew its minimum content from Article 22. But Article 21 had nothing to offer to Article 22. Now Article 21 also contributes to Article 22. The matters on which Article 22 is silent now draw their contents from Article 21. This is particularly true in respect of laws relating to preventive detention which besides Article 22 have also to conform to the requirement of Article 21 at least to the extent to which such requirements are not inconsistent with the express provisions of Article 22.

Article 23: Prohibition of traffic in human beings and forced labour

This article embodies two declarations. Firstly, traffic in human beings, beggars and other similar forms of forced labour are prohibited. The prohibition applies not only to the state but also to private persons, bodies and organisations. Secondly, any contravention of the prohibition shall be an offence punishable in accordance with the law. Under Article 35 of the Constitution laws punishing acts prohibited by this article shall only be made by Parliament, though existing laws on the subject, until altered or repealed by Parliament, are saved.

Traffic in human beings means to deal in men and women like goods, such as to sell or let it otherwise dispose of. It would include traffic in women and children for immoral or other purposes. The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1959 is a law made by Parliament under Article 35 of the Constitution for the purpose of punishing acts that result in traffic in human beings. Slavery is not expressly mentioned but there is no doubt that the expression “traffic in human beings” would cover it. Under the existing law, whoever imports, exports, removes, buys, sells or disposes of any person as a slave shall be punished with imprisonment.

In pursuance of Article 23, the bonded labour system was abolished and declared illegal by the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976.

Article 32: Remedies for enforcement of rights conferred by this part

This article describes the last of the fundamental rights. Unlike other rights, it is remedial and not substantive in nature. But it is in no way less important than the other rights. Just as the remedy of habeas corpus is called the bulwark of liberties in England, this article has been called the heart and soul of the Constitution. In the words of Dr Ambedkar; “if I was asked to name any particular article in this Constitution as the most important – an article without which the Constitution would be a nullity – I could not refer to any other article except this one. It is the very soul of the Constitution and the very heart of it…”

Even if the courts could be approached in the absence of this article, the fact of its being a fundamental right to approach directly the highest court of the country assigns special significance given to the fundamental rights in the Constitution which has been further recognized and strengthened by declaring this article part of the basic structure of the Constitution. Even well before the recognition of the basic structure of the Constitution, the court had recognized its special position in the following words:

“The fundamental right to move this Court can, therefore, be appropriately described as the cornerstone of the democratic edifice raised by the Constitution. That is why it is natural that this Court should, in the words of Patanjali Sastri J, regard itself “as the protector and guarantor of fundamental rights”, and should declare that “it cannot, consistently with the responsibility laid upon it, refuse to entertain applications seeking protection against infringements of such rights.” In discharging the duties assigned to it, this Court has to play the role “of a sentinel on the qui vive”, and it must always regard it as its solemn duty to protect the said fundamental rights “zealously and vigilantly.”

National Human Rights Commission: Organizations and functions

The NHRC was established on 12th October, 1993 and its statute is contained in the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993. The establishment of NHRC is in compliance with the Paris Principles that were accepted at the 1st International Workshop on National Institution on Promotion and Protection of Human Rights held in Paris, 1991, sanctioned by the United Nations General Assembly in Resolution 48/134 on December, 1993. The commission is a representation of India’s interest in the promotion and protection of Human Rights.

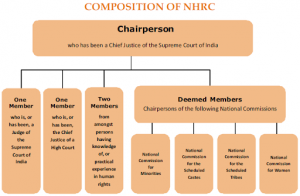

Composition of National Human Rights Commission

Functions and powers of the Commission

The Commission performs the following functions, i.e.:

Investigates, suo motu or on a petition brought to it by a victim/ any person on his behalf, into complaint of;

- The violation of human rights;

- The negligence in the prevention of such violation, by a public servant;

- To intervene in any proceeding relating to any allegation of violation awaiting before a court with the approval of such court;

- To visit, with a report made to the state government, any jail/ any other institution under the regulation of the state government, where persons are imprisoned/ lodged for purposes of treatment, reformation/ protection to study the living conditions of the prisoners and make suggestions;

- To review the precautions provided by/ under the Constitution/ any law for the time being in force, for the preservation of human rights and suggest actions for their effective application;

- To review the reasons, as well as acts of terrorism that hinder the enjoyment of human rights and suggest effective remedial measures;

- To study treaties and other international instruments on human rights and make suggestions for their effective application;

- To undertake and encourage research in the sphere of human rights;

- To spread human rights literacy amongst numerous divisions of society and to encourage awareness of the defences accessible for the protection of these rights through journals, media, and other available means; and

- To inspire the efforts of NGOs and organizations working in the field of human rights.

Role of NHRC in safeguarding human rights

Since its creation, NHRC has widely dealt with subjects relating to the implementation of human rights. NHRC has established its name for independence and integrity. There is an ever-increasing number of grievances addressed to the Commission seeking redressal of complaints. NHRC has followed its mandate and priorities with determination and considerable success.

Some of the well-known interventions of NHRC contains campaigns against discrimination against HIV patients. It also has requested all State Governments to report the cases of custodial deaths/ rapes within 24 hours of occurrence failing to do so would be assumed that there was an attempt to suppress the event. A significant intervention of the Commission was in relation to Nithari Village in Noida, where children were sexually abused and brutally mutilated. Lately, NHRC helped bring out a multi-crore pension scam in Haryana. It also looked up the sterilization catastrophe of Chhattisgarh.

International Conventions on human rights

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination was adopted by the UNGA in December, 1965. Switzerland consented to the Convention in November, 1994.

The CERD obliges State parties to pursue by all appropriate means a policy of eliminating racial discrimination in all its forms and promoting understanding among all races, refrain from all acts and practices of racial discrimination and prohibit and prosecute such acts.

The Convention defines racial discrimination and lists civil, political, economic, social and cultural human rights whose enjoyment must be guaranteed to everyone without distinction as to race. It also contains the basic right to effective judicial complaint procedures in the case of all acts of racial discrimination.

The Convention was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 21 December 1965 and came into force on 4 January 1969. Switzerland ratified the Convention on 29 November 1994, where it came into force exactly one month later.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights contains important guarantees for the protection of civil and political rights. It was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 16 December, 1966. Switzerland acceded to the Convention on 18 June, 1992.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) guarantees traditional civil rights and freedoms. Together with the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), it enacts in a binding framework the rights set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.

The ICCPR includes inter alia the following human rights:

- Protection of physical integrity Right to life, prohibition of torture, prohibition of genocide.

- Prohibition of discrimination on the grounds of race, colour, gender, language, religion, political position, fortune, origins, etc.

- Prohibition of slavery and forced labour, arbitrary detention, protection of the dignity of people deprived of their liberty.

- Procedural rights

- Freedom of thought, religion, movement and freedom of assembly.

- Political rights Right to vote and stand for election, equal access to public office

The ICCPR was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 16 December 1966 and came into force on 23 March 1976. Switzerland ratified the Convention on 18 June 1992, where it came into force on 18 September that year.

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

The UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women obliges states parties to take all appropriate means to eliminate discrimination against women. It was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 18 December 1979. Switzerland ratified the Convention on 27 March 1997.

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) sets out in detail the prohibition of discrimination against women in all stages of life and obliges states parties to take appropriate measures to this end.

The Convention:

- Defines discrimination against women.

- Provides the basis for realising equality between women and men.

- Obliges the state parties to actively adopt measures to achieve equality between women and men.

The CEDAW was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 18 December 1979 and came into force on 3 September 1981. Switzerland ratified the Convention on 27 March 1997. On 26th April, 1997, it came into force in Switzerland.

Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

The Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment obliges the states parties to prevent and punish acts of torture. It was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 10 December 1984. Switzerland acceded to the Convention on 2 February 1986.

The Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) obliges the states parties to take all necessary measures to prevent and punish torture and cruel treatment. Persons in detention are to be protected against attacks on their physical and mental integrity.

The Convention:

- Prohibits torture in all circumstances.

- Prohibits the extradition of persons to a state where there are substantial grounds for believing that she or he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.

- Provides a detailed definition of torture.

- Regulates the punishment and extradition of torturers.

- Regulates the prevention and clarification of cases of torture.

The CAT was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 10 December 1984 and came into force on 26 June 1987. Switzerland acceded to the Convention on 2 February 1986, where it came into force on 26 June 1987.

Convention on the Rights of the Child

The Convention on the Rights of the Child contains provisions on the human rights of young people under 18 years of age. It was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 20 November 1989. Switzerland ratified the Convention on 24 February 1997.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) provides a comprehensive guarantee of the human rights of young people under 18 years of age. The rights enshrined in the Convention are intended to enable children to develop their personality and abilities to their fullest potential and take into account their particular need for protection.

The Convention guarantees a child’s right to:

- Be heard and to participate.

- Protection of his or her welfare.

- An identity.

- Life, survival and development.

- Protection from abuse and exploitation.

- And includes a ban on any form of discrimination.

The Convention was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 20 November 1989. Switzerland ratified the Convention on 24 February 1997, where it came into force on 26 March that year.

Conclusion

“Human rights are extremely important because they provide fairness and equality in our society. Human rights allow all people to live with dignity, freedom, equality, justice, and peace. Every person has these rights simply because they are human beings. They are guaranteed to everyone without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinions, national or social origin, property, birth, or another status. Human rights are essential to the full development of individuals and communities. Many people view human rights as a set of moral principles that apply to everyone. Human rights are also part of international law, contained in treaties and declarations that spell out specific rights that countries are required to uphold. Countries often incorporate human rights in their own national, state, and local laws.”

Human rights are important in the relationships that exist between individuals and the government that has power over them. The government exercises power over its people. However, human rights mean that this power is limited. States have to look after the basic needs of the people and protect some of their freedoms

“Human rights reflect the minimum standards necessary for people to live with dignity and equality. Human rights give people the freedom to choose how they live, how they express themselves, and what kind of government they want to support, among many other things. Human rights also guarantee people the means necessary to satisfy their basic needs, such as food, housing, and education, so they can take full advantage of all opportunities. Finally, by guaranteeing life, liberty, and security, human rights protect people against abuse by individuals and groups who are more powerful.”

Reference

- https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/resources/handbook-for-parliamentarians-on-the-convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/chapter-two-the-convention-in-detail-5.html

- https://www.humanrights.is/en/human-rights-education-project/human-rights-instruments/global-human-rights-instruments/un-human-rights-conventions

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

https://t.me/joinchat/J_0YrBa4IBSHdpuTfQO_sA

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications