I discuss the current law on deportation subject to diplomatic assurances, in the backdrop of the judgement of Othman (Abu Qatada) v. the United Kingdom[1] and conclude that though deportation with assurances (“DWA”) are extremely controversial, particularly since they are not legally binding, they are not always insufficient to meet the receiving state’s obligations: if the assurances cover the prohibited activities, relate to a situation over which the assuring state has control, and come from a reliable source then arguably, the receiving States can rely on it. [2]

In Sweden for instance, extraditions have been permitted on the basis of DWAs despite the deficiency of an extradition treaty with Rwanda, even though higher evidentiary standards have been applied.[3] Similar arrangements are being made in Germany, where the extradition of two Rwandese genocide suspects to Rwanda is at the moment under scrutiny on the basis of its international mutual legal assistance legislation.[4] Likewise, France does not require an express bilateral extradition treaty for an extradition to Rwanda to proceed. To date, three differently composed trial chambers of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (“ICTR”) have rejected three requests of the Prosecution to transfer cases to Rwanda.[5] At the same time, the French Cour d’Appel de Chambery[6] and the City of Westminster Magistrates’ Court[7] approved the extradition of genocide suspects to Rwanda. But the substantive questions still remain unanswered – Are DWAs lawful under International law; and if yes, when and how?

-

The Strasbourg Position on DWA:

The obligation of non-refoulement, or the obligation not to return an individual to a country where he is likely to be subjected to torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment under Article 3 of the European Convention of Human Rights (“ECHR”) has been clearly established as an absolute one by the ECtHR in Soering v United Kingdom[8], Chahal v United Kingdom[9] and Saadi v. Italy[10]. However, some governments, including the U.K. have of late argued that even in the absence of an extradition treaty, they ought to be entitled to deport suspected terrorists to countries where they may be at risk of torture or ill-treatment or other flagrant risks provided they have acquired diplomatic assurances from the receiving country that the individual will be protected from such treatment. This forms the basis of my discussion in this article.

The ECtHR in Babur Ahmad[11] clarified that it has always underlined that the “absolute nature of Article 3 does not mean that any form of ill-treatment will act as a bar to removal from a Contracting State,” pointing out that the Convention does not purport to impose Convention standards on other states. In fact, the ECtHR is always very cautious in finding that removal from the territory of a Contracting State would be contrary to Article 3 of the Convention. One of the reasons is that the violation of Article 3 closely depends upon the facts of the particular case to be readily established in an extradition context. For instance, the ECtHR in Babur Ahmad acknowledged that “save for cases involving the death penalty, it has even more rarely found that there would be a violation of Article 3 if an applicant were to be removed to a State which had a long history of respect of democracy, human rights and the rule of law.”

Following the jurisprudence of the ECtHR, it is clear that the real risk test[12] and the assessment of the facts (including the current human rights situation in the receiving country and characteristics specific to the applicant) in any individual case must remain central to the deportation and extradition policy. The line of authority both pre and post-Othman illustrates that the court expects to conduct a robust assessment of the reliability of assurances, and will not shy away from finding a violation, particularly in cases involving an Article 3 claim that the individual faces a real risk of being subjected to torture, inhuman or degrading treatment on his return.[13] While the ECtHR did not allow the extradition in Chahal (because it did not find the assurances to be sufficient in light of the “violation of human rights being a recalcitrant and enduring problem in Punjab, India”[14]) and Saadi (because the Govt. of Tunisia had not adduced any evidence capable of rebutting the assertions made by the sources of Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch describing numerous cases of torture), even though it followed the same principles in Babur Ahmad and Abu Qatada, the outcome was very different.

In Babur Ahmad, the ECtHR found that there would be no violation of Article 3, ECHR if the United Kingdom extradited the applicants to the United States and imprisoned them at the “ADX Florence” for there were sufficient procedural guarantees in place for deciding on such transfers, and ruled that the violation of Article 3 if an applicant were to be removed to a State which had a “long history of respect of democracy, human rights and the rule of law”, was rare.

Hence, the Court engaged into an independent assessment of the general human rights situation prevalent in the U.S.A. and held that if the applicants were convicted under the present charges, there would be justification for considering them a security risk and imposing restrictions on their contacts with the outside world. It further found that the conditions at ADX Florence were adequate and that psychiatric services would be available there. As regards the risk of mandatory sentences of life imprisonment, the ECtHR, having regard to the seriousness of the offences, did not consider them to amount to inhuman or degrading treatment.[15]

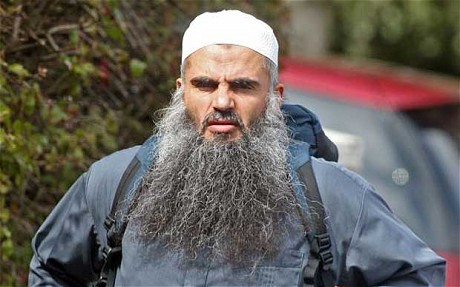

The ECtHR in Abu Qatada held that the arrangements entered into between Jordan and the United Kingdom in 2005 as part of the Memorandum Of Understanding and monitoring provisions (cumulatively “assurances”) would provide sufficient safeguards against the risk of torture or inhuman and degrading treatment and that, as a result, Article 3, 13 and 5 of the ECHR would not be violated, were the applicant (Abu Qatada) to be deported to Jordan.[16]However, by a unanimous verdict, it also ruled that Abu Qatada could not be lawfully deported to Jordan, holding that his deportation would be in violation of Article 6, ECHR (“flagrant breach of the relevant right”[17]) on account of the real risk of the admission at the applicant’s retrial of evidence obtained by torture of third persons, overturning the U.K. House of Lords (who had unanimously come to the opposite conclusion) in R.B. Algeria v. Secretary of State.[18]

The Grand Chamber however, on 9 May 2012 refused to consider Abu Qatada’s requestthat his case be transferred to the Grand Chamber on appeal, without according any reason, though accepting that the appeal application was lodged in time. Possibly, the question of whether a Memorandum of Understanding is accepted is largely a question of fact, not law, and therefore less likely to have required the Grand Chamber’s attention.[19] Accordingly, the UK can rely upon diplomatic assurances in relation to Abu Qatada not being tortured, but cannot deport him until it has valid assurances that the evidence obtained under torture will not be used in Qatada’s trial. Though the UK govt. claims it has these assurances, the Courts have still not confirmed it.

I now analyze the Qatada judgment[20] and highlight all the criteria that were kept in mind by the ECtHR prior to making it’s decision:

- ‘Real-risk’ of ill-treatment eliminated by Assurances:

Though the ECtHR in Abu Qatada accepted a myriad of documents – open source information system and submitted in evidence attesting to systemic torture in Jordanian detention facilities[21] painting a picture of those facilities that was as “consistent as it was disturbing”[22], yet, the ECtHR held that “any real risk of ill treatment [under Article 3] was, in fact, removed[23] by the assurances provided by the Jordanian authorities”.[24]

However, the ECtHR refused to accept that assurances could counter the real risk of a “flagrant denial of justice” under Article 6, ECHR. It ruled that: “in the course of the proceedings before this Court, the applicant has presented further concrete and compelling evidence that his co-defendants were tortured into providing the case against him. He has also shown that the Jordanian State Security Court has proved itself to be incapable of properly investigating allegations of torture and excluding torture evidence, as Article 15 of UNCAT requires it to do. His is not the general and unspecific complaint that was made in Mamatkulov and Askarov; instead, it is a sustained and well-founded attack on a State Security Court system that will try him in breach of one of the most fundamental norms of international criminal justice, the prohibition on the use of evidence obtained by torture. In those circumstances, and contrary to the applicants in Mamatkulov and Askarov, the present applicant has met theburden of proof required to demonstrate a real risk of a flagrant denial of justice if he were deported to Jordan.”[25]

2. Initial Assessment of general human rights situation in the receiving country:

The ECtHR in Abu Qatada was extremely careful to explain its view that “in any examination of whether an applicant faces a real risk of ill treatment in the country to which he is to be removed, the Court will consider both the general human rights situation in that country and the particular characteristics of the applicant.

Accordingly, the Court scrutinized the data and information that was available, from possibly all potential sources and formulated a separate section in the judgment called “Section IV. Human Rights in Jordan”. It recorded the detailed findings of the United Nations Report on Human Rights Council, The Committee against Torture, The Report submitted by the Special Rapporteur, The Human Rights Committee Reports of the Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the Jordanian National Centre for Human Rights and the United States Department of State 2009 Human Rights Report and engaged in it’s own independent analysis of the detailed provisions of the ECHR, UNCAT and entered into an examination of comparative case-law analysis, discussing the French, German and Spanish law, reasoning why extradition had been refused on grounds where the receiving State’s authorities had failed to dispel concerns regarding the dismal human rights conditions [“Section V. Relevant Comparative and International Law on Torture and the use of Evidence obtained by Torture”].

In Mahjoub[26], the Canadian Court summed up the importance of this independent initial assessment, finding that

“[the factors under consideration here] provide a ‘cautious framework’ for any analysis of the trustworthiness of assurances given by a foreign government. For instance, a government with a poor human rights record would normally require closer scrutiny of its record of compliance with assurances. A poor record of compliance may in turn require the imposition of additional conditions, such as monitoring mechanisms or other safeguards which may be strongly recommended by international human rights bodies. Conversely, a country with a good human rights record would often likely have a correspondingly good record of compliance, and therefore additional conditions may be unnecessary to enhance the reliability of assurances.”

3. Preliminary laches: Exclusion of Assurances owed to general HR situations prevailing in receiving country:

The ECtHR added that “in assessing the practical application of assurances and determining what weight is to be given to them, the preliminary question was whether the general human rights situation in the receiving State excludes accepting any assurances whatsoever.” It added that it would only be in rare cases that the general situation in a country would mean that no weight at all can be given to assurances.[27]

4. Assurances cannot form sole basis of Deportation:

The ECtHR in Abu Qatada explained that

“in a case where assurances have been provided by the receiving State, those assurances constitute a further relevant factor which the Court will consider. However, assurances are not in themselves sufficient to ensure adequate protection against the risk of ill treatment. There is an obligation to examine whether assurances provide, in their practical application, a sufficient guarantee that the applicant will be protected against the risk of ill-treatment.”

This also falls in line with Lord Phillips’ views from Mamatkulov and Askarov, which treat assurances “as part of the matrix that had to be considered” when deciding if there were substantial grounds to believe that the applicant would face ill treatment contrary to Article 3, ECHR. He referred to the “abundance of international law material” which supported the proposition that assurances given should be treated with skepticism if they are given by a country where inhuman treatment by State agents was endemic.

5. Assessment of Quality and Reliance on Assurances:

The ECtHR then elucidated that “More usually, the Courts will assess first, the quality of assurances given and, second, their reliance i.e. whether, in light of the receiving State’s practices they can be relied upon.” In doing so, the Courts will have regard to specific considerations; inter alia, the following factors[28]:

- whether the terms of the assurances have been disclosed to the Court[29];

- whether the assurances are specific or are general and vague [30];

- who has given the assurances and whether that person can bind the receiving State[31];

- If the assurances have been issued by the central government of the receiving State, whether local authorities can be expected to abide by them[32];

- whether the assurances concerns treatment which is legal or illegal in the receiving State [33];

- whether they have been given by a Contracting State[34];

- the length and strength of bilateral relations between the sending and receiving States, including the receiving State’s record in abiding by similar assurances[35];

- whether compliance with the assurances can be objectively verified through diplomatic or other monitoring mechanisms, including providing unfettered access to the applicant’s lawyers [36];

- whether there is an effective system of protection against torture in the receiving State, including whether it is willing to cooperate with international monitoring mechanisms (including international human rights NGOs), and whether it is willing to investigate allegations of torture and to punish those responsible [37]

- whether the applicant has previously been ill-treated in the receiving State [38]; and

- whether the reliability of the assurances has been examined by the domestic courts of the sending/Contracting State.[39]

6.Contextual element (circumstances under which assurances are given):

The ECtHR also attached significant weight to assurances being given in good faith by the Government of Jordan whose bilateral relationship with the UK, which historically, have been very strong (Babar Ahmad[40] and Ors.; Al-Moayad[41]). It echoed the SIAC, stating that “the assurances must be viewed in the context in which they are given”[42]. To specify, it held that the weight to be given to assurances from the receiving State depends, in each case, on thecircumstances prevailing at the material time.” [43]

The judgements of the ECtHR namely Chahal v. the United Kingdom[44] and Mamatkulov and Askarov v. Turkey[45], also depict that reliance could lawfully be placed on assurances; but the weight to be given depended on the circumstances of each case. Interestingly, these two judgements argued that there was a difference between relying on an assurance which required a State to act in a way which would not accord with its normal law and an assurance which required a State to adhere to what its law required but which might not be fully or regularly observed in practice.

The ECtHR also heavily relied upon the fact that Mr Othman’s high profile in the mediawould militate in favour of the Jordanian authorities ensuring that he was properly treated[46], which was another contextual element, under which the assurances were given.

7. Nature of Assurances (MOU) to be assessed independently- Question of fact

ECtHR jurisprudence implies that the nature of the documents on which assurances are based, be it the MOU signed between the U.K. government and receiving country or the monitoring provisions, ought to be carefully considered. For instance, the ECtHR in Abu Qatada held that the MOU signed between the highest authorities of Jordan and the UK was “specific, comprehensive, superior to any assurances examined by the UN Committee against Torture and UNHRC in the cases of Agiza, Alzery and Pelit and had withstood the extensive examination that had been carried out by an independent tribunal, SIAC , which had the benefit of receiving evidence adduced by both parties, including expert witnesses (such as senior immigration lawyers) who were subject to extensive cross-examination.”[47] This requirement could also be camouflaged with that of the detailed factors to be analyzed to determine the‘quality of assurances’, as elucidated in this article.

This requirement was reinforced by the findings of the SIAC which accept that “there were some weaknesses in the MOU and monitoring provisions signed between Jordan and the UK”[48] . However, this was yet again, justified by SIAC, basing its reliance on the basis that there was no real risk of ill-treatment for most of the protections were implicitly covered, in light of the prevailing facts and circumstances such as long-standing relations between Jordan and UK, high profile of the applicant etc. The same requirement was reiterated in Abu Qatada by the Court in Para 151 as well, where the Court quoted the Swedish case law –Mohammed Alzery v. Sweden [49] wherein it was held that neither were the assurances sufficient nor was their any mechanism for their enforcement . The Court added that “11.3 …. The existence of diplomatic assurances, their content and the existence and implementation of enforcement mechanisms are all factual elements relevant to the overall determination of whether, in fact, a real risk of proscribed ill-treatment exists.”

To elucidate, assurances may usurp multiple forms, inter-alia others (1) Note Verbale; (2) Memorandum of Understanding (3) Aide-Memoire – An informal summary of a diplomatic interview or conversation that serves merely as an aid to memory; (4) Pro Memoria; (5) Note Diplomatique; (6) Note Collective; and (7) Circular Diplomatic Note.

For instance, in Abu Qatada, assurances comprised of the MOU dated 10 August 2005; a side letter from the United Kingdom Chargé d’Affaires, Amman, to the Jordanian Ministry of the Interior, which recorded the Jordanian Government’s ability to give assurances in individual cases that the death penalty would not be imposed and questions as to the conduct of any retrial he would face after deportation were also put to the Jordanian Government and answered in May 2006 by the Legal Adviser at the Jordanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs; twoNote Verbales exchanged between the United Kingdom Embassy in Jordan and the Jordanian Government wherein the parties had indicated their understanding that: (i) if a returnee was detained within three years of return, the MOU provided for monitoring until such a time as he was released and, potentially, indefinitely; and (ii) a returnee who was detained more than three years after return, would not be entitled to monitoring visits.[50]

In fact, to further buttress its arguments, the U.K. Government produced two statements, from Mr. Anthony Layden, a former diplomat and currently United Kingdom Special Representative for Deportation with Assurances before the ECtHR in Abu Qatada as ‘further evidence’ on assurances.[51] The first statement, dated 24 September 2009, outlined the closeness of ties between the United Kingdom and Jordan, the United Kingdom’s support for various initiatives to enhance human rights in Jordan, as well as various reports (summarised at paragraphs 106–124), which showed Jordan’s improving human rights record.[52]

The second statement also provided an overview of recent reforms in Jordan, including changes to the criminal law to introduce more severe penalties for serious crimes such as torture and measures to increase press freedom. The statement also summarised Jordan’s submissions to the United Nations Committee against Torture in the course of the Committee’ consideration of Jordan’s second periodic report.[53] Mr Layden rejected any suggestion that “there would be no incentive to reveal breaches of the MOU; failure to abide by its terms would be likely to do serious damage to diplomatic relations; action proportionate to any breach would certainly be taken by the United Kingdom Government. For the Adaleh Centre, he stated that there was nothing unusual in the fact that it had not carried out any monitoring in Jordan thus far; it operated on a project basis by developing proposals, seeking funding and implementing initiatives. Its NTCT had already visited Qafqafa prison on 9 May 2010. The Centre was not financially motivated; it had lost money by agreeing to act as the monitoring body. Nor was it a for‑profit organisation; it was required to return any surplus for projects to donors. Nothing turned on its change to a limited liability company”.

8. Need for verification and Monitoring:

Besides obtaining assurances, the ECtHR made the need for effective verification abundantly clear in Othman.[54] In fact, the arrangements made for the involvement of the Adaleh Centrein the monitoring of the agreement in place was central to the Court’s analysis.[55] This also reflects the conclusion of their Lordships in RB (Algeria)[56] that “an assurance, the fulfillment of which is incapable of being verified would be of little worth.”

In the House of Lords decision of RB (Algeria) (FC) and another (Appellants) v Secretary of State for the Home Department[57], Lord Phillips[58] agreed that effective verification is required, but that it can be achieved by means other than monitoring as well. Lord Hoffman[59] agreed that effective verification was required stating that, “in my [his] opinion SIAC was quite right to say that although fulfillment of the assurances must be capable of being verified emphasis added, external monitoring is only one possible form of verification.” He also acknowledged in the same paragraph that “in the absence of some provision for external monitoring … assurances may be no more than empty words.” Thus there is nothing to caste doubt on the proposition that effective verification is essential for DWA to become a universal and successful practice.

In fact, in the Abu Qatada case, Paragraph 4 of the Terms of Reference for the Monitoring Body (viz. The Adelah Centre) – in respect of detention were extracted and reverberated in the ECtHR judgment in Paragraph No. 81. To clarify, the terms of reference for the Adaleh Centre (the monitoring body) specifically provided that

“the monitoring body must be operationally and financially independent of the receiving State and must be able to produce frank and honest reports. The terms of reference also state that it must have capacity for the task, with experts (“Monitors”) trained in detecting physical and psychological signs of torture and ill-treatment and access to other independent experts as necessary. A Monitor should accompany every person returned under the MOU (“returned person”) throughout their journey from the sending State to the receiving State, and should go with them to their home or, if taken to another place, to that place. It should have contact details for a returned person and their next of kin and should be accessible to any returned person or next of kin who wishes to contact it. It should report to the sending State on any concerns rose about the person’s treatment or if the person disappears. For the first year after the person returns, a Monitor should contact him or her, either by telephone or in person, on a weekly basis.” [60]

B. The U.K.’s position on DWA:

The UK Courts, including Special Immigration Appeals Commission (“SIAC”) apply a four-part test to determine if assurances can be relied on in a particular case. They look at the terms of the assurances, consider whether they were given in good faith, look for an objective reason to believe that the assurances will be honoured and require the assurances to be capable of verification.[61]

The U.K. Courts have found assurances to be sufficient for Algeria (see SIAC’s determinations in G (8 February 2007); Z and W (14 May 2007) Y, BB and U (2 November 2007); PP (23 November 2007); B (30 July 2008); T (22 March 2010); Sihali (no. 2) (26 March 2010)). It also found them to be sufficient in respect of Ethiopia in the case of XX (10 September 2010). SIAC also found assurances to be insufficient in respect of Libya, given the changeable nature of the then Gaddafi regime (DD and AS (27 April 2007)).

In January 2015, in the case of BB, PP, W, U & Ors v Secretary of State for the Home Department[62], the Court of Appeal has recently over turned a judgment of the SIAC upholding the lawfulness of the UK government’s reliance upon DWA of five Algerian appellants and remitted them to SIAC for further consideration. The Court of Appeal held that the SIAC had misdirected itself on the correct threshold test for Article 3 claims and had adopted the wrong approach to whether ‘assurances’ that the appellants would not be subjected to serious ill-treatment could be properly verified. Hence, it appears that the English Courts require the applicants to meet a higher threshold to be established for there to be a real risk of ill treatment as compared to the ECtHR.

Referring to authorities like Peers v. Greece[63], Babar Ahmad v. United Kingdom[64] andBatayav v. SSHD[65], the Court of Appeal ruled that the minimum level of severity “depends on all the circumstances of the case, such as the duration of the treatment, its physical and mental effects and, in some cases, the sex, age and state of health of the victim”; and that, in considering whether treatment is “degrading”, the court “will have regard to whether its object is to humiliate and debase the person concerned and whether, as far as the consequences are concerned, it adversely affected his or her personality in a manner incompatible with Article 3”.[66]

It then referred to Babar Ahmad for the observation that

“the Convention does not purport to be a means of requiring the contracting states to impose Convention standards on other states …..This being so, treatment which might violate Article 3 because of an act or omission of a contracting state might not attain the minimum level of severity which is required for there to be a violation of Article 3 in an expulsion or extradition case”.[67] Finally, it relied on Batayav for the proposition that unlawful conditions of detention in a receiving state can only be established by “a consistent pattern of gross and systematic violation of rights under Article 3”.[68]

Hence, the English as well as Strassbourg Courts reject a distinction between domestic and extra territorial context, extradition and removal cases[69] and a comprehensive binary distinction between torture and inhuman or degrading treatment cases.

In SIAC’s determination of the Abu Qatada case, which was concurred by the House of Lords, the government relied on the nature of its bilateral relationship with the receiving country i.e. Jordan when assessing that assurances were credible and reliable at the risk of torture. Infact, the details of the negotiations and the bilateral relationship were therefore examined assiduously by SIAC. The level of control exercised over the agencies likely to come into contact with (and detain) the applicant on return were scrutinised, such as the Adelah Monitoring Centre. The political situation in the country was examined in detail, including procedural aspects of its laws and courts. There was also considerable analysis of verification mechanisms, such as access to detainee, independence of monitor, role of international non–governmental organisations. Evidently, this was no cursory analysis, exactly akin to the approach of the ECtHR.

C. Aggregate Law of factors involved in DWA:

-

Real risk’ of ill-treatment in the receiving country:

The ECtHR held that examination of the existence of a risk of ill-treatment in breach of Article 3 at the relevant time must necessarily be a rigorous one in view of the absolute character of this provision and the fact that it enshrines one of the fundamental values of a democratic society making up the Council of Europe.[70]

In Vilvarajah and Others v. United Kingdom[71] five Tamils were refused asylum in the UK and they returned to Sri Lanka but then continued to suffer ill-treatment. However, their complaints to Strasbourg (for judicial review) were rejected under both Articles 3 and 13, ECHR on the sole basis that they did not meet the high threshold to be established for there to be a real risk of ill treatment.

Subsequently, in the case of Chahal v. United Kingdom[72], the ECtHR emphasized the fundamental nature of Article 3 in holding that “the prohibition was made in “absolute terms … irrespective of a victim’s conduct.” Stating that Article 3, ECHR would be violated if the deportation order to India were to be enforced, the judgement built itself on the landmark case of Soering v United Kingdom (1989), and was considered an example of the British government losing a seminal legal case in the ECtHR on the aspect of DWA.

In Mohammed Alzery v. Sweden,[73] the United Nations Human Rights Committee considered the removal of an Egyptian national to Egypt by Sweden, pursuant to diplomatic assurances that had been obtained from the Egyptian government. On the merits of the case, the Committee found that the State party has not shown that the diplomatic assurances procured were in fact sufficient in the present case to eliminate the risk of ill-treatment to a level consistent with the requirements of article 7 of the Covenant. [74]

2. Political opponents, members of illegal organizations, persons accused of terrorism, etc.:

In the case of Shamayev and Others v. Georgia and Russia[75], the Court upheld that the threshold of Article 3 would be met, if applicant was to be extradited to his native country of Russia on the ground that he was a terrorist rebel who had taken part in the conflict in Chechnya. However, in Babar Ahmad and Others v. the United Kingdom and Abu Qatada, the ECtHR held that there would be no real risk ill-treatment (Article 3) upon extradition of the applicants.

In Saadi v. Italy, although the ECtHR accepted the grave difficulties that contemporary terrorism poses to states, it rejected the argument offered by the U.K. government, which was a third party intervener to the proceeding, that in relation to suspected terrorists the court ought to weigh the community interest against the risk of violatory conduct perpetrated by a third party state (in this case, Tunisia). The Court accepted that diplomatic assurances might be sufficient in some cases to satisfy a state’s Article 3 obligations, but this was not the case here given the strong evidence of widespread torture and ill-treatment in Tunisian detention facilities. Thus, Saadi could not be deported for his deportation would violate Article 3.

3. Membership of a stigmatised ethnic minority group:

In Makhmudzhan Ergashev v. Russia, the ECtHR found that Article 3 would be violated if the decision to expel a Kyrgyzstani national of Uzbek ethnic origin to Kyrgyzstan were to be enforced. The Court held that the applicant had good reason to fear that he would be tortured or subjected to inhuman or degrading treatment, in particular in view of the widespread use of torture against members of the Uzbek minority in the southern part of Kyrgyzstan.

4.Persons risking persecutions on the basis of religion:

In Sufi and Elmi v. the United Kingdom[76]: Both cases concerned the applicants’ allegation that if returned to Somalia they would be at real risk of ill-treatment. Mr Sufi, a member of a minority clan, the Reer Hamar, alleged that he has been persecuted and seriously injured by the Hawiye milita. Mr Elmi, who arrived in the United Kingdom at the age of 19, alleged that he would be seen as westernised and anti-Islamic and, if it were known that he was a drug addict with prior convictions for theft, would be at risk of being amputated or publicly flogged or killed of religious reasons. Violation of Article 3 in case of expulsion to Somalia.

In D.N.M. v. Sweden and S.A. v. Sweden[77], the applicants alleged that they would be at a risk of being the victims of an honour-related crime following their relationships with women which had met with their families’ disapproval. This argument was rejected by the Court on the grounds that the general situation in the country which was slowly improving and the applicants could always, reasonably relocate to other regions in Iraq.

5. Circumstances relating to a death sentence:

Harkins and Edwards v. the United Kingdom[78] concerned the complaint of two men that, if the U.K. were to extradite them to the United States, they risked the death penalty or sentences of life imprisonment without parole. The Court rejected as inadmissible the applicants’ complaints concerning the alleged risk of death penalty, considering that the diplomatic assurances, provided by the US to the British Government – that the death penalty would not be sought in respect of Mr. Harkins or Mr. Edwards – were clear and sufficient to remove any risk that the applicants could be sentenced to death if extradited, particularly as the US had a long history of respect for democracy, human rights and the rule of law. The Court also found that it would not be grossly disproportionate even if the US courts decided to give the applicants life sentences without parole in the US. Consequently, there would be no violation of Article 3 if they were extradited.

6.Right to private/family life:

In Balogun v. United Kingdom[79], a Nigerian national complained that his deportation would breach his right not to be ill-treated as well as his right to private life. The Court found that, although the applicant was a settled migrant, the seriousness of the multiple drugs-related offences he had committed as an adult, coupled with the carefully considered preventive steps of the UK authorities to mitigate any risk of suicide, were sufficient to justify his deportation, and upon balancing, found that Article 8 would not be violated.

7. Other Risks – “Denial of a fair trial” (Article 6, ECHR) – Abu Qatada case:

In the Court’s case-law, the term “flagrant denial of justice” has been synonymous with a trial which is manifestly contrary to the provisions of Article 6 or the principles embodied therein.[80] The ECtHR in Abu Qatada agreed with the Court of Appeal that the central issue in the present case is the real risk that evidence obtained by torture of third persons will be admitted at the applicant’s retrial. Accordingly, it is appropriate to consider at the outset whether the use at trial of evidence obtained by torture would amount to a flagrant denial of justice. In common with the Court of Appeal, the Court considers that it would.

The Courts have indicated that the following would amount to a “flagrant denial of justice”, though this list is not exhaustive:

- conviction in absentia with no possibility subsequently to obtain a fresh determination of the merits of the charge; [81]

- a trial which is summary in nature and conducted with a total disregard for the rights of the defence;[82]

- detention without any access to an independent and impartial tribunal to have the legality the detention reviewed;[83]

- deliberate and systematic refusal of access to a lawyer, especially for an individual detained in a foreign country.[84]

It is noteworthy that, in the twenty-two years since the Soering judgment, the Court has never found that an expulsion would be in violation of Article 6. This fact, when taken with the examples given in the preceding paragraph, serves to underline the Court’s view that “flagrant denial of justice” is a stringent test of unfairness. It goes beyond mere irregularities or lack of safeguards in the trial procedures such as might result in a breach of Article 6 if occurring within the Contracting State itself. What is required is a breach of the principles of fair trial guaranteed by Article 6 which is so fundamental as to amount to a nullification, or destruction of the very essence, of the right guaranteed by that Article. In assessing whether this test has been met, the Court considers that the same standard and burden of proof should apply as in Article 3 expulsion cases. Therefore, it is for the applicant to adduce evidence capable of proving that there are substantial grounds for believing that, if he is removed from a Contracting State, he would be exposed to a real risk of being subjected to a “flagrant denial of justice”. Where such evidence is adduced, it is for the Government to dispel any doubts about it (Saadi v. Italy).

On 8 April 2009, the High Court of Justice, Divisional Court, Great Britain (UK) hearing the appeal against extradition of Vincent Brown aka Vincent Bajinja, Charles Munyaneza, Emmanuel Nteziryayo, Celestin Ugirashebuja v. The Govt. of Rwanda and The Secretary of State for the Home Department [85] concluded that that the appellants [5 ‘category one’ suspects]should not be sent back to Rwanda because of the real risk of a “flagrant denial of justice” by reason of their likely inability to adduce the evidence of supporting witnesses.[86] It explained that the ‘Organic Law’ was limited as to make provision only for witnesses in cases transferred from the ICTR and that there was no evidence as to how these provisions work in practice.[87] It seems as though the government of Rwanda and the judge had placed much reliance on the Organic Law, but available case law virtually has no evidence of its application in real cases.

To further elucidate, there was no extradition treaty between the UK and Rwanda and the British authorities did not consider themselves to be in a position to prosecute the suspects directly due to a lack of universal jurisdiction over the crime of genocide. Consequently,British and Rwandan authorities signed Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) in respect of each of the suspects in September 2006, in effect putting into place legal instruments‘whereby Rwanda could submit and the British could receive their extradition requests’. Though the Human Rights Watch agreed with the U.K. court’s assessment that they would not be guaranteed a fair trial in Rwanda, it, however also criticized the court’s decision to release the four men instead of recommending their prosecution in the UK. [88] It appears as though the Govt. of Rwanda will soon push an appeal against this decision of the UK High Court of Justice on grounds that “the country [i.e. Rwanda] has proven itself on the international standards of a fair justice system, has abolished the death penalty, suspects get required legal assistance and the conditions in prisons are conducive, and does not understand why can’t these suspects be sent”. [89]

(*Shriya is a practicing advocate at the Supreme Court of India, the Delhi High Court and district courts at New Delhi. She is a graduate of Gujarat National Law University, India and University of Oxford. At Oxford, she completed her Bachelor of Civil Law programme on a full scholarship and obtained a Master’s in Law majoring in International Crime. A recipient of the Oxford Global Justice Award 2015 for Public International Law, she is currently assisting the President of the International Residual Mechanism for the Criminal Tribunals (MICT).)

________________

[1] Abu Qatada v. The U.K. Application No. 8139/09 dated 17 January 2012, delivered by the ECtHR.

[2] This is a very broadly defined criteria, in line with the International human rights law that has developed three main principles relative to the adequacy of diplomatic assurances which I discuss in due course of this Memorandum – (i) the promise itself must be adequate; (ii) the matter in relation to which the promise is made must be within the control of the promisor; and (iii) the promisor must enjoy credibility in relation to the matter at hand and in relation to the promisee state.” as cited by LONDRAS, F.: Ireland´s potential liability for extraordinary renditions through Shannon airport. Available athttp://www.academia.edu/1762038/BABAR_AHMAD_AND_OTHERS_v._THE_UNITED_KINGDOM. Last accessed on 21.1.2016 at 10:30 A.M.

[3] The ECtHR in Ahorugeze v. Sweden in Application no. 37075/09, Judgment delivered by ECtHR on 27 October 2011 held that that it was safe to extradite Sylvère Ahorugeze, the Rwandan genocide suspect arrested in Sweden and dismissed his holding that there were no reasons to believe that Ahorugeze would be subjected to inhumane or unfair treatment in Rwanda and that he would not receive a fair trial and. The court also noted that “experience gathered by Dutch investigative teams and the Norwegian police during missions to Rwanda, concluded that the Rwandan judiciary cannot be considered to lack independence and impartiality.” Ahorugeze appealed this decision before the ECHR Grand Chamber but the latter decided not to review the case in June 2012.

[4] Gesetz über die internationale Rechtshilfe in Strafsachen in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 27. Juni 1994 (BGBGL. I S.1537), zuletzt geändert durch Artikel 1 des Gesetzes vom 6. Juni 2008 (BGBL. I S. 995) for a copy of the legislation (in German) seehttp://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/irg/index.html (last accessed August 2008); see also AFP, 8 July 2008, “Ruandischer Kriegsverbrecher in Frankfurt gefasst”, available (in German) athttp://www.123recht. net/Ruan discher-Krie gsverb recher-in-Frankfurt-gefasst__a31270.html (last accessed August 2008).

[5] Case No: CO/6247/2008, Judgment delivered by the dated 08.04.2009 by the High Court of Justice Divisional Court on Appeal and Review.

[6] Decision on 2 April 2008 of the Cour d’Appel de Chambery, Chambre de l’instruction 2008/00082, No 2008/88; this decision was overturned by the Cour de Cassation, Chambre Criminelle, No Y 08-82.922 F-D, 9 July 2008.

[7] The City of Westminster Magistrates’ Court in the case of The Government of the Republic of Rwanda v. Vincent Bajinya, Charles Munyaneza, Emmanuel Nteziryayo, Celestin Ugirashebuja, 6 June 2008.

[8] Para 91, (1989) 11 EHRR 439

[9] Para. 80, (1996) EHRR 413

[10] Application no. 37201/06, February 2008, delivered by the ECtHR.

[11] Applications nos. 24027/07, 11949/08, 36742/08, 66911/09 and 67354/09, delivered on 10 April 2012 by the ECtHR.

[12] The ECtHR held that the assurances contained in the MOU, accompanied by monitoring by Adaleh, removed any real risk of ill-treatment of the applicant. Abu Qatada v. The U.K.Application No. 8139/09 dated 17 January 2012.

[13] For examples of cases subsequent to the decision in Othman, see inter alia: Labsi v Slovakia, App. No.33809, 15 May 2012, Asimov v Russia, Appo.67474, 18 April 2013, Sidikovy v Russia, App.73455/11,

20 June 2013, Nizomkhon Dzhurayev v Russia,App .31890/11, 3 October 2013, Ermakov v Russia, App. No.

o.43165/10, 7 November 2013, Kasymakhunov v Russia, no.29604/12, 14 November 2013. See also Mahmatkulov v Turkey, App Nos46827/99 and 46951/99, 4 February 2005 (GC).

[14] Para. 105, Chahal v. The U.K.

[15] Page 82, Applications nos. 24027/07, 11949/08, 36742/08, 66911/09 and 67354/09, delivered by the ECtHR on 10 April 2010.

[16] Page No.s 91, 92, Court’s decision in Abu Qatada v. The U.K. Application No. 8139/09 dated 17 January 2012.

[17] I discuss this aspect of the judgment at length in the last section of this article titled“Aggregate law of factors involved in DWA”.

[18] [2009] UK HL 10.

[19] Available at http://ukhumanrightsblog.com/2012/05/09/reports-abu-qatada-appeal-was-in-time-but-will-not-be-heard-by-grand-chamber/ , last accessed on 26 January 2016.

[20] Abu Qatada v. The U.K. Application No. 8139/09 dated 17 January 2012, delivered by the ECtHR.

[21] Ibid, Para 107, UN Committee Against Torture, Para 108, UN Human Rights Committee, Paras 109 – 111,Special Rapporteur on Torture, Paras 112 – 115, Amnesty International, Paras 116 – 118, Human Rights Watch.

[22] Para 191, Abu Qatada case.

[23] The usage of the word ‘removed’ could hint at the line of authority that though there was a plausible risk, but not a ‘real risk’ posed , for it was eliminated due to the superior quality and reliance of the diplomatic assurances given by the State of Jordan.

[24] Para 205, Abu Qatada case.

[25] Paras.281-287, Abu Qatada case.

[26] Para 153, Mahjoub v. Canada 2006 FC 1503

[27] Ibid, § 188 For instance, Gaforov v. Russia, no. 25404/09, § 138, 21 October 2010; Sultanov v. Russia, no. 15303/09, § 73, 4 November 2010; Yuldashev v. Russia, no. 1248/09, § 85, 8 July 2010; Ismoilov and Others, cited above, §127.

[28] Ibid, § 189, Abu Qatada v. The United Kingdom, Application No. 8139/09 dated 17 January 2012.

[29] Ryabikin v. Russia, no. 8320/04, § 119, 19 June 2008; Muminov v. Russia, no. 42502/06, § 97, 11 December 2008; see also Pelit v. Azerbaijan, cited above.

[30] Saadi¸ cited above; Klein v. Russia, no. 24268/08, § 55, 1 April 2010; Khaydarov v. Russia, no. 21055/09, § 111, 20 May 2010.

[31] Shamayev and Others v. Georgia and Russia, no. 36378/02, § 344, ECHR 2005‑III; Kordian v. Turkey (dec.), no. 6575/06, 4 July 2006; Abu Salem v. Portugal (dec.), no 26844/04, 9 May 2006; cf. Ben Khemais v. Italy, no. 246/07, § 59, ECHR 2009‑… (extracts); Garayev v. Azerbaijan, no. 53688/08, § 74, 10 June 2010; Baysakov and Others v. Ukraine, no. 54131/08, § 51, 18 February 2010; Soldatenko v. Ukraine, no. 2440/07, § 73, 23 October 2008.

[32] Chahal, cited above, §§ 105-107.

[33] Cipriani v. Italy (dec.), no. 221142/07, 30 March 2010; Youb Saoudi v. Spain (dec.), no. 22871/06, 18 September 2006; Ismaili v. Germany, no. 58128/00, 15 March 2001; Nivette v. France (dec.), no 44190/98, ECHR 2001 VII; Einhorn v. France (dec.), no 71555/01, ECHR 2001-XI; see also Suresh and Lai Sing, both cited above.

[34] Chentiev and Ibragimov v. Slovakia (dec.), nos. 21022/08 and 51946/08, 14 September 2010; Gasayev v. Spain (dec.), no. 48514/06, 17 February 2009.

[35] Babar Ahmad and Others, cited above, §§ 107 and 108; Al‑Moayad v. Germany (dec.), no. 35865/03, § 68, 20 February 2007;

[36] Chentiev and Ibragimov and Gasayev, both cited above; cf. Ben Khemais, § 61 andRyabikin, § 119, both cited above; Kolesnik v. Russia, no. 26876/08, § 73, 17 June 2010; see also Agiza, Alzery and Pelit, cited above;

[37] Ben Khemais, §§ 59 and 60; Soldatenko, § 73, both cited above; Koktysh v. Ukraine, no. 43707/07, § 63, 10 December 2009;

[38] Koktysh, § 64, cited above.

[39] Gasayev; Babar Ahmad and Others¸ § 106; Al-Moayad, §§ 66-69.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Al‑Moayad v. Germany (dec.), no. 35865/03, § 68, 20 February 2007;

[42] § 195, Othman (Abu Qatada) v United Kingdom, Application No. 8139/09, 17 January 2012.

[43] § 187, Abu Qatada v. The United Kingdom, Application No. 8139/09 dated 17 January 2012, delivered by the ECtHR. Please see Saadi v. Italy [GC], no. 37201/06 § 148.

[44] 15 November 1996, Reports of Judgments and Decisions 1996‑V

[45] nos. 46827/99 and 46951/99, ECHR 2005‑I

[46] Othman (Abu Qatada) v the United Kingdom, App No.8139/09, § 196, 17 January 2012

[47] Ibid, § 194

[48] Ibid, § 31

[49] CCPR/C/88/D/1416/2005, 10 November 2006

[50] para. 90, Othman (Abu Qatada) v the United Kingdom, App No.8139/09, § 196, 17 January 2012.

[51] Othman (Abu Qatada) v the United Kingdom, App No.8139/09, § 196, 17 January 2012, § 83.

[52] Para 83, 84, Ibid

[53] para.107, Ibid

[54] §§ 193 – 205, Othman (Abu Qatada) v United Kingdom, Application No. 8139/09, 17 January 2012.

[55] Ibid, §§ 202-204. See “..for these reasons, the court is satisfied that, despite its limitations, the Adelah Centre would be capable of verifying that the assurances were respected.”

[56] 2009 UKHL 10

[57] [2009] UKHL 10

[58] Para 124, Ibid

[59] Para 193, Ibid

[60] Para. 81, Ibid

[61] BB –v- SSHD, SC/39/2005, Mitting J at Para 5.

[62] [2015] EWCA Civ 9

[63] (2001) 33 EHRR 51

[64] (2013) 56 EHRR 1

[65] [2003] EWCA Civ 1489

[66] Para 68, BB, PP, W, U & Ors. v. SSHD.

[67] Para. 176

[68] Para 7, BB, PP, W, U & Ors. v. SSHD.

[69] Para 176, Babur Ahmad Judgment.

[70] Infra.

[71] (1991) 14 EHRR 248

[72] (1996) 23 EHRR 413

[73] CCPR/C/88/D/1416/2005, 10 November 2006

[74] Para 11.5 “the assurances procured contained no mechanism for monitoring of their enforcement or implementation. The mechanics of the visits failed to conform to key aspects of international good practice by not insisting on private access to the detainee and inclusion of appropriate medical and forensic expertise, even after substantial allegations of ill-treatment emerged.” In light of these factors.”

[75] Application no. 36378/02 dated 12/04/2005, ECtHR

[76] Applications nos. 8319/07 and 11449/07 dated 28/06/2011, ECtHR.

[77] Application nos. 28379/11 and 66523/10 both dated 27/06/2013, ECtHR

[78] 9146/07 [2012] ECHR 45

[79] [1989] Imm AR 603

[80] Sejdovic v. Italy [GC], no. 56581/00

[81] Einhorn, cited above, § 33; Sejdovic, cited above, § 84; Stoichkov, cited above, § 56

[82] Bader and Kanbor, cited above, § 47

[83] Al-Moayad, cited above, § 101.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Case No: CO/6247/2008, Judgment delivered by the dated 08.04.2009 by the High Court of Justice Divisional Court on Appeal and Review.

[86] Ibid, Paras. 66 and 121.

[87] Ibid, Para 64.

[88] See letter from Human Rights Watch to UK Justice Secretary Jack Straw regarding amendment of the International Criminal Court Act of 2001, May 12, 2009,http://www.hrw.org/news/2009/05/12/letter-uk-justice-secretary-jack-straw-regarding-amendment-international-criminal-co, and Human Rights Watch, “UK: Put Genocide Suspects on Trial in Britain: UK Prosecution Preferable to Extradition,” November 1, 2007,http://www.hrw.org/news/2007/11/01/uk-put-genocide-suspects-trial-britain.

[89] Please see http://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/article/2015-12-24/195537/ , last accessed on 26 January 2016.

About author

Ms. Shriya Maini is an advocate practicing at the Supreme Court of India, the Delhi High Court and district courts at New Delhi. She specializes in dispute resolution, focusing on civil and criminal litigation, family and property law matters. After completing her Bachelors from Gujarat National Law University, she joined the Litigation & Arbitration department of erstwhile Amarchand Mangaldas & Suresh A. Shroff, New Delhi as an Associate in their Dispute Resolution Team. She then pursued the BCL (Bachelor of Civil Law) programme on a full scholarship and obtained a Master’s in Law from the University of Oxford, majoring in International Crime. A recipient of the Oxford Global Justice Award 2015 for Public International Law, she is currently working at the United Nations, The Hague, The Netherlands since 2nd January 2016, assisting the President of the International Residual Mechanism for the Criminal Tribunals (MICT), a UN court of law dealing with war crimes that took place during the Balkans in the 1990’s .”

Ms. Shriya Maini is an advocate practicing at the Supreme Court of India, the Delhi High Court and district courts at New Delhi. She specializes in dispute resolution, focusing on civil and criminal litigation, family and property law matters. After completing her Bachelors from Gujarat National Law University, she joined the Litigation & Arbitration department of erstwhile Amarchand Mangaldas & Suresh A. Shroff, New Delhi as an Associate in their Dispute Resolution Team. She then pursued the BCL (Bachelor of Civil Law) programme on a full scholarship and obtained a Master’s in Law from the University of Oxford, majoring in International Crime. A recipient of the Oxford Global Justice Award 2015 for Public International Law, she is currently working at the United Nations, The Hague, The Netherlands since 2nd January 2016, assisting the President of the International Residual Mechanism for the Criminal Tribunals (MICT), a UN court of law dealing with war crimes that took place during the Balkans in the 1990’s .”

The article was originally published at https://ilsquare.wordpress.com/2016/01/30/does-international-law-permit-deportation-with-assurances/

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications

The Court accepted that diplomatic assurances might be sufficient in some cases to satisfy a state’s Article 3 obligations, but this was not the case here given the strong evidence of widespread torture and ill-treatment in Tunisian detention facilities.http://lawgupshup.com/category/jobs/ after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely delighted I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back often!

Pretty nice post.