This article is written by Shivali Srivastava from National Law University Odisha. This article throws light on the judicial system of Mughal era and the division of courts. It further points out the criticism of the same.

Table of Contents

Introduction

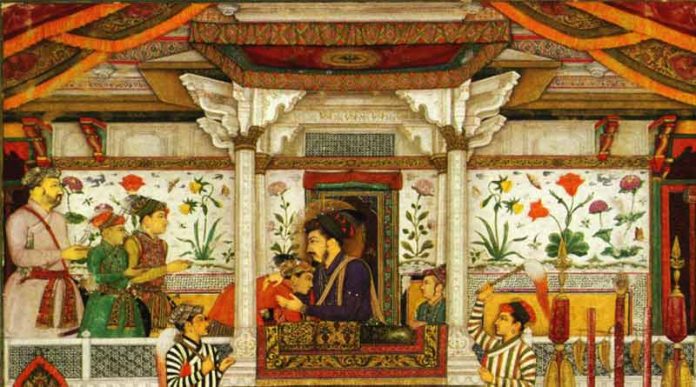

Following the collapse of the Sultanate of Delhi in India in 1526 C.E. Mughal rule emerged in India. Babur, who was also the first emperor of the Mughal Empire, founded the Mughal rule in India. His son Humayun, who conquered many other parts of India, succeeded him. It is believed that the Mughal emperors were very fond of justice and were considered the ‘fountain of justice.’ The emperor set up a separate justice department called Mahakuma-e Adalat to govern and then see the proper administration of justice within the empire. The laws were based largely on the Holy book of Islam- Quran. This was similar to the sultanate of Delhi, as the sultanate’s laws were also based on the Quran. Sovereignty resides in Allah (God) and according to the Quran, and the King is his faithful servant in carrying out his will on earth. The ruler was considered to be the judge, the appointed representative of the Almighty who was sent to make justice among the subjects in his province.

Classification of the court during the Mughal empire

At the capital seat in provinces, districts, praganahs, and villages, a systematic classification and gradation of the courts existed. The significant courts that operated during this period were as follows:

Court systems at capital

India’s capital city Delhi had its courts divided into three. They were as follows:

The Emperor’s Court

The Emperor’s court, which was controlled by the emperor, was the court of the empire’s highest order. The said court has jurisdiction over the case civil as well as criminal cases. The Emperor was supported by Daroga-e-Adalat, Mir Adil & Mufti when hearing the cases as a court of first instance. The Emperor presided over a bench consisting of the Chief Justice (Qazi-ul-Quzat) and other chief justice court Qazis while hearing the appeal.

The Chief Justice’s Court

It was the capital’s second significant courtroom. The said court was controlled over by the Chief Justice which was supported by two highly essential Qazies who were appointed as puîne judges who were working in this court. It had jurisdiction and the discretion to hear civil, original as well as criminal cases and hear provincial court appeals as well. These also had supervisory authority over the operation of the Provincial tribunals.

The Chief Revenue Court

It was the third relevant court of appeal to entertain those cases involving revenue. The four officials, namely Daroga-e-Adalat, Mir Adil, Mufti and Muhtasib have also supported this court. In addition to these three important courts, Delhi already had two courts. Qazi-e-Askar court was a court that was especially where military matters were determined. The court travelled with troops from place to place.

Provincial Courts

The provinces that were present in the Mughal period were divided into smaller units called Subahs. Each Subah had its own court. These courts in the subahs were divided into three types:

The Governor’s Court (Adaalat-e-Nasim-e-Subah)

The Governor or Nazim control and handle this court and presides over all the cases which deal in matters relating to Province, which is known as his original jurisdiction. This court also had the authority to hear lower court appeals. Further appeal from this court rested with the court of the Emperor. At this court were attached one Mufti and a Daroga-e-adalat.

The Provincial Chief Appeal Court (Qazi-i-Subah’s court)

This tribunal heard appeals from the district Qazis’ decisions. Qazi-i-Subah ‘s forces coexisted with those of the Governors. This court also had original jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters. Mufti, Muhtasib, Daroga-e- Adalat-e-Subah, Mir Adil, Pandit, Sawaneh Nawis and Waque Nigar were the officers attached to this court.

Provincial Chief Revenue Court

At the imperial capital, this court was taken over by the Diwan-e-Subah who possessed original as well as appellate jurisdiction. Peshker, Daroga, Treasurer and Cashier were four officers annexed to this court.

District Court

The districts in the Mughal Period were known as Sarkars. These Sarkars were divided into four courts. The courts were as follows:

District Qazi Court

Qazi-e-Sarkar presided over the district’s chief civil and criminal court. This court had the authority to try both civil and criminal cases. The Qazi-e-Sarkar ‘s appeal from this court was the district’s chief judicial officer. Daroga-e-Adalat, Mufti, Mir Adil, Muhtasib, Pandit, and Vakil-e-Sharayat were appointed to this court with six officers.

Faujdaar Adalat

This particular court was usually presided over by a Faujdar who had the authority to prosecute riot and state security cases. From this court’s rulings, an appeal lay before the court of the governor.

Kotwali trial

A Kotwal-e-Shahar presided over this court ruled on all minor criminal cases. That court’s appeals lay with the Qazi-e-Sarkar.

Amalguzari Kachari

This court was chaired by an Amalguzar who decided revenue items. An appeal by this court lay with the Adalat of Diwan-e-Subah.

Important Officers in Mughal Empire for the administration of justice

The administration of justice was in the hands of a few officials who were held responsible for any injustice and providing aid to all the residents of the empire.

Vakil

The Vakil’s office seems to have taken on prominence when Akbar was a minor and Bairam Khan served as a deputy on his behalf. The office lost significance after that. Though the title continued to exist, none were appointed to work for the emperor. It slowly lost its importance and faded completely during Shah Jahan’s reign.

Mukhtasib

He was the public-moral censor. It was his duty to follow the Prophet’s orders and to suppress all those un-Islamic activities. Also within the censor province lay the punishment of heretical opinions, especially against the Prophet and the neglect by Muslims of the five daily prayers and observance of Ramzan. They were granted the task during Aurangzeb ‘s period to demolish newly-constructed temples. They were also asked to ensure the use of accurate weights and measurements.

Chief Qazi

Chief Qazi was the top judicial officer and was responsible for conducting justice effectively and efficiently. It was the Emperor’s duty as the khalifa of the age to give justice to the people, but since he had no time, the work was given to the Qazi chief. He was the only Judge in religious suits and tried them by Muslim statute. He named the Qazis of the Cities, Districts, and Provinces. The muftis supported certain Qazis. The majority of the Qazis had been corrupt. According to Sir Jadunath Sarkar, “All the Mughal era Qazis were infamous for taking bribes with a few honourable exceptions.”

Kotwal

Kotwal’s duties are set forth in the book Ain-i-Akbari. He was essentially a city police officer, but in some cases, he was responsible for maintaining law and order in the city, he enjoyed magisterial powers. He kept watch at night and patrolled the city. He kept a housing register and frequented buildings. He looked at weight and measurements and noticed robbers. He made a list of those who had no successor, and of the person who was dead and missing. He was to see that according to sati pratha no woman was burned against her will

Crime and punishment in Mughal Administration

Two Muslim codes, namely Fiqh-e-Firoz Shahi and Fatwai-i-Alamgiri, governed the judicial procedure. Proof has been categorized into three categories

- absolute corroboration

- single-person testimony

- admission including confession. The court has always preferred full backing to other classes of evidence. Muslim criminal law classified crimes broadly into three types:

(i) crimes against Allah (God)

(ii) crimes against Shahenshah (King) and

(iii) crimes against individuals.

Trial by trial as occurred in Hindu Period during the Muslim Era was forbidden. The courts have then executed three kinds of punishment under Muslim law for above three kinds of crimes-

Hadd (Fixed Penalties)

It is the type of punishment imposed by the law of the cannon that could not be reduced or changed by human agency. Hadd has meant specific punishment for particular offences. Thus it offered a fixed penalty for crimes such as stealing, rape, whoredom (zinah), apostasy (ijtidad), slander and drunkenness as laid down in Sharia law. It applied equally to Muslims and non-Muslims. The State was under an obligation to prosecute all Hadd culprits. Under it no compensation has been given.

Tazir (Discretionary Punishment)

It was another type of punishment that meant prohibition and applied to all crimes not classified under Hadd. All offences against King or the Shahenshah were offences for which Tazir was fixed. It contained offences such as gambling, injury-causing, minor theft etc. Under tazir the kind and the sum of punishment was left solely with the wish of the judge; which meant that courts had the discretionary power to create new methods of punishment.

Qisas (retaliation) and Diya (Blood money)

In fact, Qisas meant life for life and limb for limb. Qisas has been applied to cases of wilful killing and certain types of serious wounding or mutilation characterized as crimes against the human body. Qisas was considered the victim’s personal right or his next kin’s right to inflict on the wrongdoer like injury as he had inflicted on his victim.

Administration of justice

The Hindus and Muslims have tried both civil and criminal cases at the Qazis. When attempting the Hindus cases they were expected to take their customs and use into consideration. They were required to be “just truthful, unbiased to hold trials in the presence of witnesses and at the courthouse and government headquarters, not to acknowledge gifts from the individuals they served, nor to attend any and everybody’s entertainment, and they were asked to know poverty as their glory.” Despite this ideal, their powers were abused by the Qazis general and “in Mughal times the Qazis departments became a word of reproach.”

The Qazis were mainly judges. He did perform a number of other roles though. Hewas needed to fulfil political, religious, and clerical responsibilities. He acted as an official revenue while performing the function of the jizya collection and that of the advertising treasury admin. The registrar’s employment in the registry of sale-deeds, mortgage deeds, conveyances, gift deeds, and the like, and the magistrate’s recognition of bail-bonds, sure-bonds, certificate farmers, and documents are also relevant to his office. He had also been expected to perform a wide number of varied nature religious functions. His judicial work must have been severely impaired by the huge diversity of functions

Criticisms of Mughal Administration

- No distinction was drawn between public law and private law under Muslim criminal law. Criminal law was seen as a private branch of law. The notion that crime was an offence not only against the injured person but also against society, had not been created.

- Muslim criminal law was experiencing considerable illogicality. This is because crimes against god have been considered crimes of an atrocious nature. Offences against men were viewed as private offences and retribution was considered the party’s private right.

- Under Muslin criminal law the most ineffective rule was Diya’s clause. In other instances, the killer survived simply by paying money to the assassinated person’s dependants. From this produced other evil practices.

- No specific provisions in Muslim law were available in cases where the murdered person left no descendants to punish the murdered or to claim blood-money. A minor heir waited until he reached a majority to punish the murderer or claim blood-money.

- While Muslim law sought to differentiate between murder and guilty homicide, the guilty party’s intent or lack of intent did not rest. It relied on the type of weapons used to commit the crime. That was peculiar and caused serious injustice.

Conclusion

The administration of justice during the Mughal era was very poor and reached its highest peak during Akbar’s reign, and its consistency dropped under Aurangzeb’s reign. We see a strong classification of courts at different levels, but there were no laws to test their working in a loyal manner. We see the officials becoming greedy and taking bribes to do the job they’ve been paying a salary for. There was no decentralization of authority that contributed to such maladministration of the legal system. Warren Hastings rightly said “the Mughal legal system was a very simple and often barbaric and inhumane structure”

References

- http://southasiajournal.net/judicial-system-of-mughal-and-british-india/#:~:text=Judicial%20administration%20of%20Mughals,system%20of%20justice%20took%20shape.&text=Every%20provincial%20capital%20had%20its,Supreme%20Qazi%20of%20the%20empire.

- https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/16633/9/09_chapter%204.pdf

- https://books.google.com/books/about/Judicial_System_of_the_Mughal_Empire.html?id=kgGYPgAACAAJ

- https://www.academia.edu/12096011/legal_system_in_mughal_empire

- https://www.ijsr.net/archive/v3i12/U1VCMTQxMDQ3.pdf

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications