This article is written by Abhishek Nair, pursuing a Diploma in M&A, Institutional Finance, and Investment Laws (PE and VC transactions) from LawSikho.com.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Till the mid-2000s, corporate India was yet to successfully pull off a leveraged buy-out. The concept was extremely popular in the American and European markets having been introduced in the 1980s and made widely popular by the Leveraged Buy-Out of RJR Nabisco by US private equity giant Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR), the events of which were later immortalised into a book and a TV show. The first-ever successful case of a leveraged buy-out by any Indian company was done when Tata Tea acquired the UK heavyweight brand Tetley for the staggering price of US $450 million which was more than four times the net worth of Tata tea which stood at the US $ 114 million. The present article shall deal with the financial structure of an LBO and how smaller companies like Tata Tea were able to utilise the structure of LBOs to buy these gargantuan companies like Tetley. It shall also delve deeper into the legal challenges in leveraging an Indian buyout and how it can be made possible in India.

Leveraged buyouts (LBO)

In a leveraged buyout, a company is acquired by a specialised investment firm using a relatively small portion of equity and a relatively large portion of outside debt financing. The leveraged buyout investment firms today refer to themselves (and are generally referred to) as private equity firms. This is also called ‘bootstrapping acquisition.’

The process of a listed company being acquired by a non-strategic buyer (usually a private equity firm) with a short-term investment goal and subsequently delisted is usually referred to as a PTP or a public-to-private transaction. Since most of these transactions are financed through borrowing at substantially high rates, they are called leveraged buyouts (LBOs) or highly-leveraged transactions (HLTs). LBOs are generally split into four types based on their management system:

-

Management Buyout (MBO)

This is a type of LBO in which the target company’s existing management bids for the control of the firm which is usually supported by a third-party private equity investor.

-

Management buy-in (MBI)

It is an LBO in which an outside management team acquires (often backed by a third-party private equity investor) a company and replaces the incumbent management team. The company was subsequently delisted.

-

Buy-in management buyout (BIMBO)

Another type of LBO in which the bidding team comprises members of the incumbent management team and externally-hired managers, often alongside a third-party private equity investor.

-

Institutional buyout (IBO)

When the new owners of a delisted firm are solely institutional investors or private equity firms, one tends to refer to these transactions as institutional buyouts (IBOs) which are sometimes also called Bought Deals or Finance Purchases. Incumbent management can be retained and may be rewarded with equity participation.

Regulatory and legal restrictions on LBO

The western model of LBOs is facing down the barrel of the gun wielded by the various statutory laws in India. Despite a well-established debt market in India, the regulations imposed by the Reserve Bank of India as well as laws such as the Companies Act have acted as a barrier to the growth of the LBO sub-sect of mergers and acquisitions.

- The Companies Act, 2013 does not allow a listed and unlisted public limited company to provide security for the acquisition of its shares and consequently restricts the ability to undertake a typical leverage buyout. A traditional LBO where debt is raised by using the company‘s assets as collateral is not permitted for public companies in India.

- The above-mentioned restriction does not apply to a private company hence a listed public company could theoretically delist its securities and convert itself into a private company before being acquired via an LBO. This comes with its own set of problems. In order to voluntarily delist, a company needs the approval of at least two-thirds of its members and from the stock exchanges on which it is listed. Delisting would also require the company to follow the complex delisting guidelines of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) (Delisting of Equity Shares) Regulations, 2009.

- Furthermore, to convert to a private company, it would also need approval from the registrar of companies, which can consider many factors, such as whether a majority of the shareholders have consented to the conversion, and whether there are any objections from the company‘s shareholders and creditors.

- The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has created restrictions to prevent Indian banks from granting loans to borrowers for the purchase of shares in an Indian company.

- Domestic banks are not allowed to finance the promoters’ contribution towards the equity capital of a company. Granting advances against primary security of shares and debentures including promoters’ shares to industrial, corporate, or other borrowers is not allowed. The RBI only allows accepting such securities as collateral for secured loans granted as working capital or for other ‘productive purposes’ from borrowers.

- The RBI created an exception to the abovementioned rule in order to increase the Indian influence in foreign markets and has allowed domestic banks to lend to Indian companies for purchasing equity in foreign joint ventures, wholly-owned subsidiaries, and other companies as strategic investments.

- The Indian laws allow for companies to fund overseas acquisitions through external commercial borrowings within the overall limit of US$500 million per year under the automatic route with the conditions that the overall remittances from India and non-funded exposures should not exceed 200% of the net worth of the company.

The above list of rules and regulations has created a scenario where the buyout of Indian companies has largely been restricted while there is a bit more leeway granted in the acquisition of foreign companies. The previously mentioned case of Tata Tea’s acquisition of Tetley was made possible through the relaxation of the various restrictions that had been placed by Indian regulatory bodies. Despite these restrictions, there are few ways through which leveraging an Indian buyout can take place.

Structuring an LBO in India

The Reserve Bank of India has given a framework which slightly changed the existing regulation wherein banks are not allowed to finance the acquisition of promoter stake in Indian companies, in a discussion paper that “Leveraged buyouts will be allowed for specialized entities for the acquisition of ‘stressed companies.” To structure an LBO is a far more complicated task that is limited to very few options, foreign holding company structure, and the asset buyout structures.

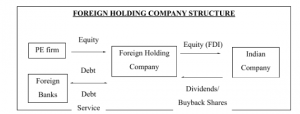

Foreign holding company structure

In this type of structure, the financial investor incorporates a foreign holding company (FHC). The FHC is then financed using equity and debt mode of financing which is raised entirely from foreign banks. The proceeds gained through the equity and debt issue are used by the FHC to purchase equity in the target Indian company with compliance to FIPB Press Note 9 in the form of FDI. The seller of the Indian operating company may be involved in the LBO and receive benefits such as rollover equity and seller notes. The reason this model can bypass the Indian restrictions is that the obligation to pay back the debt lies within the foreign company hence; it doesn’t attract the attention of Indian regulatory boards. The Indian company to facilitate the debt service pays dividends/ sells shares for a buyback.

Things to take into consideration

- Choice of jurisdiction: It is recommended that buyers and PE firms should focus on setting up the foreign holding company in a country that can easily acquire the borrowing it needs as well as has suitable treaties with India to serve the debt and facilitate the future exit. Countries like Mauritius and Singapore are recommended for this purpose because of the ease of doing a transaction with these countries.

- Lien on Assets: Because of the regulatory challenges, it is difficult to use the assets of the newly acquired Indian company as collateral for the debt owed by the FHC. In such situations, businesses in the service and technology sector are far more suitable because of the nature of their assets which can be set up as collateral for the debt.

- Foreign currency risk: – The difference in currency makes this type of LBO riskier than traditional LBO as the ability to pay back the borrowing is dependent on the relationship between the currency of the foreign country and Indian National Rupees (INR). The fluctuations in this relationship might increase the overall cost of undertaking an LBO.

- Dividend Tax: – As mentioned before, the Indian company pays the FHC dividends to serve its debts. This results in the accrual of Dividend Distribution Tax which has to be factored in the costs of undertaking an LBO.

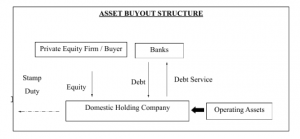

Asset buyout structure

In this type of structure, the financial investor incorporates a domestic holding company under the Companies Act, 2013. This company is then financed using the equity and debt mode of financing. This debt is raised using an asset purchase agreement that stipulates to buy operating assets and uses these assets as the security for the debt. This is done in compliance with the secured project and working capital loan’s structure which allows for asset-backed loans. The holding company shall then purchase the operating assets of the target Indian company on an asset-by-asset basis. Foreign Investors can also invest in equity of the holding company through FDI. It is generally high enough to make the LBO of an asset-intensive company unattractive and unfeasible. The process of identifying, valuing each asset separately, and then assessing the stamp duty makes this a very complex structure that is risky.

Things to take into consideration

Things to take into consideration

- Stamp duty: The domestic holding company will be liable to pay stamp duty on the operating assets it purchases. The rate of stamp duty depends upon the state, but it is generally high enough to make the LBO of an asset-intensive company unattractive and unfeasible. The process of identifying, valuating each asset separately, and then assessing the stamp duty makes this a very complex structure that is risky.

- Lien on asset: This will generally be available in this type of structure as Indian banks allow asset-backed loans.

- Higher tax liability for sellers: – This structure leads to a higher tax liability than that in the Foreign Holding Structure. This is because the sale of assets is treated as revenue by the Income Tax Act, and this gain is assessed as business income on which the tax rate is extremely high factoring in surcharge and cess tax.

Conclusion

Both the FHC structure as well as the asset buyout structure are ways to leverage an Indian Buyout by bypassing the restrictive regulatory and statutory laws regarding LBOs. Both of these structural models have emphasised non-asset-intensive companies due to the problems listed before. This is why the most preferred industry sector for LBOs in India is considered to be outsourcing companies, service companies, and high technology companies. These companies are more labour-intensive than asset-intensive which makes these companies still be able to reach high rates of growth and make the LBO successful. Another benefit of these types of companies is that they earn most of their revenue from exports denominated in foreign currency which reduces the risk of foreign currencies associated with the foreign holding company structure. These companies are also largely situated in Special Economic Zones and software technology parks which reduce the tax implications as these areas have low tax rates due to tax incentive schemes.

In 2006, the private equity giant KKR (mentioned before), acquired Flextronics Software Systems and GE Capital International Services (GECIS) was sold for $500 million to private equity firms General Atlantic Partners and Oak Hill Capital Partners in 2004. These both were technology and outsourcing-based firms which were able to succeed because of their company structure. This is how to leverage an Indian buyout in this restrictive environment.

References

- Steven N. Kaplan and Per Strömberg, Leveraged Buyouts and Private Equity, Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 22, Number 4, Season 2008.

- Renneboog, Luc and Vansteenkiste, Cara, Leveraged Buyouts: A Survey of Literature (January 1, 2017). European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI) – Finance Working Paper No. 492/2017, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2896653 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2896653

- Luc Renneboog Cara Vansteenkiste, Leveraged Buyouts: A Survey of the Literature, January 2017, Working Paper N° 492/2017

- https://www.rbi.org.in/circulars/circject/download98b%5CDBOD.No.%20Dir.BC.90_13.07.htm.

- Early Recognition of Financial Distress: -Prompt Steps for Resolution and Fair Recovery for Lenders: Framework for Revitalising Distressed Assets in the Economy, Reserve Bank of India, 30th January 2014.

- Could You Leverage Your Indian Buyout?, Deloitte, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/in/Documents/tax/thoughtpapers/in-tax-LeveragedBuyouts(LBOs)-noexp.pdf

Students of LawSikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

https://t.me/joinchat/J_0YrBa4IBSHdpuTfQO_sA

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications