This article is written by Chaitanya Suri, pursuing a Diploma in Cyber Law, Fintech Regulations and Technology Contracts from LawSikho.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Cyber-flashing is becoming the 21st century form of sexual harassment. In the era of technology, where sending a message or media post is immediate, one seldom cares about what they are sending. People use their online identities to experience a sense of comfort. This contributes to careless and irresponsible behaviour by individuals, particularly towards the most disadvantaged, such as women and children. This is not so that men don’t experience online harassment, but there are other segments of society that encounter much more severe online harassment. Cyber flashing is one type of such cyber abuse. Many people are victims of cyber flashing without becoming conscious of it. An individual may be cyber flashed by anyone who might be close by using “Airdrop” in iOS, “Nearby” in Android, or some other file sharing app; or perhaps by someone sitting in any corner of the world by sharing an audio or video file. As a result of the pandemic triggered by COVID-19, the sensitivity towards the concept has increased as cases of cyber harassment have increased however there exists legal voids. A few jurisdictions have a cyber flashing regulation while in the majority of countries cyber flashing is not expressly identified as a crime.

What does cyber flashing mean

Flashing in the physical world refers to intentional indecent exposure of one’s body in a public space thereby causing harassment (mostly sexual) to an individual. If the act is carried out using the internet as a means, then cyber flashing is established. It is the sending of unsolicited indecent material (which involves GIFs, film, images, audio, links) which is sexual or obscene in nature is submitted without the consent of the receiver. It undoubtedly corresponds to sexual harassment.

A 2020 illustration of cyber flashing harassment will be a case of an intruder trying to disrupt the video call, uploading racial and obscene material. Then there are pranks which are used to obscure cyber flashing, for example, several of us have once received a chat or instant message which contains pornographic photos and sexual noises. Such messages are often sent by friends but at times they are meant for fun and not maliciousness. Unfortunately, due to various reasons such as lack of direct laws, weak enforcement and society in which we live, females do not report such incidents. In a patriarchal society such as India, getting an unsolicited explicit message online may escalate to the female being faulted for the cyber blast. Consequently, people indulging in such acts get a free pass with no fear of law or authorities.

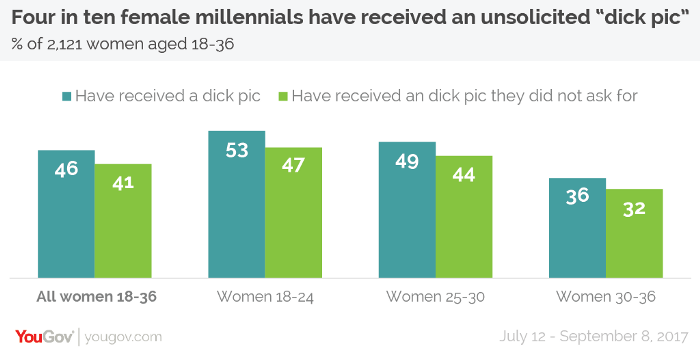

In a YouGov survey of 1,000 people, almost 40% recorded having got an unsolicited photo of a man’s genitalia. Respondents claimed they’d got the media without having consented to it. This is 89% among a limited group of women, being sent genital images in unsolicited texts. The research showed that 40% of adult women who received unsolicited photographs were under 18 when they first received them. This is notwithstanding the reality that transmitting an obscene picture to a juvenile is unconstitutional. The study discussed in this article was conducted about three years ago. Imagine where these figures may be right now.

Source: YouGov

It’s not specific to women, even children are targeted by cyber flashers. Though transmitting pornographic material to children is illegal, underaged victims are unable to comprehend the seriousness of the case, rendering unreported cases of cyber flashing to kids is a real concern. They might not be able identify what material has flashed in front of them and they might not understand that they’ve been flashed.

Legal situation in India

The bulk of such incidents remain unreported as these crimes are digital and mostly anonymous. Therefore, the current laws in force are not of much value. The need of the hour is special legislation acknowledging and tackling this abuse. A handful of jurisdictions have adopted a law against cyber flashing, including Singapore, the US state of Texas, and Scotland, while the UK has introduced the drafting of a law to define cyber flashing as a type of sexual assault.

In India, there exist laws on sexual harassment which cover cyber harassment as well. Such guidelines could also be used against cyber flashing. The ‘IT Act, 2000’ is the prima facie statute that deals with the country’s cyber crimes. Although there is no clear legislation on cyber flashing, it could be construed to include the same under Sec 67 of the Act. The sections note that: “Punishment for publishing or transmitting obscene material in electronic form – Whoever publishes or transmits or causes to be published or transmitted in the electronic form, any material which is lascivious or appeals to the prurient interest or if its effect is such as to tend to deprave and corrupt persons who are likely, having regard to all relevant circumstances, to read, see or hear the matter contained or embodied in it, shall be punished on first conviction with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years and with fine which may extend to five lakh rupees and in the event of second or subsequent conviction with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to five years and also with fine which may extend to ten lakh rupees.”

In essence, any person that publishes or transmits any pornographic content in electronic form or enables the same material that is likely to corrupt an individual is culpable for an offence. The likelihood of reading the text is an important ingredient in this. ‘Obscene material’ has been defined as: (i) one that is lascivious, or (ii) one that appeals to the prurient interest, or (iii) one that has the effect of depriving and corrupting individuals who are likely to read, see or hear the matter, taking into account all applicable circumstances.

Furthermore, Sec 67A clearly describes the disclosure or dissemination of content involving a sexually suggestive act or behaviour as a punishable crime. Under this clause, cyber flashing may be deemed a crime since it includes the sending of sexually suggestive activities and actions using the internet. Admittedly, such an assumption is exceedingly large in scope and arbitrary. Because the law is uniformly impartial towards a gender, any person may lodge a grievance under it.

Further, there are specific laws for children and women that allow for a better argument and have been used in India to identify the act of cyberflashing as an offence. Those legislations include:

- Section 509 of IPC deals with words, gestures or acts that are directed at damaging a woman’s modesty. Cyber flashing is an act that includes flashing the victim’s computer with pornographic photographs that is enough to generate an apprehension of terror in women’s minds. According to the clause, whoever intends to offend any woman’s modesty, to utter any words, to make any sound or gesture, or to depict any object, intending that such word or sound shall be heard, or that such gesture or object shall be seen, by such woman, shall be liable for the violation.

- On the other hand, Section 354A(iii) provides that a man who displays pornography against the will of a woman is liable and prosecuted for the crime of sexual assault. Cyber flashing directly linked to pornography, like pornographic content disguised in photographs, links or files that seem to discuss some other subject on the surface, or in situations where the sender persuades the user to open a file or media, misleading them to think that it includes anything other than the pornographic content concealed in it, is more likely to be held legally heald liable within the framework. Exposing a woman to pornography against her will over video call should also technically fall under the ambit of this section.

- In the case of minors, Section 293 of the IPC allows for the prosecution of anyone who distributes, shows or circulates some obscene object, or tries to do so, to any minor under the age of twenty years. For cyber flashing of pornography, genitals and other lewd items to minors, this section should appropriately apply. In addition, Section 13 of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act 2012, which concerns the use of children for pornographic purposes, may also apply.

In addition, the Union Home Ministry has introduced a “Cyber Crime Prevention against Women and Children” (CCPCW) platform where victims can disclose online sexual harassment, cases of rape, content from confidential sources on child sexual abuse, etc. It helps people to disclose the misuse of inappropriate material and thus provides the victims with counselling. This portal can be easily used by people to disclose cases. It accounts for the responsibility of the state to deter, identify and prosecute cyber attacks through the regime of law enforcement. Additionally, an online repository has now been rendered operational to register cybercrime incidents.

As has been pointed out, despite there being a few laws (although not sufficient) that may be used to tackle the same, disclosure of cyber-flashing cases is scarce. This is because of several reasons, foremost of them being needing to negotiate with the authorities. The lack of adequate legal preparation and police sensitization, together with the negligible amount of cyber flashing incidents recorded, makes it very probable that the police station workers does not identify in which provisions of the law the allegation should be recorded, which can be quite troubling for the claimant. The current regulation is very often insufficient and gives unpredictable explanations to issues such as the motive of the perpetrator, the victim’s consent at private/public sites. Much of this taken together makes it impossible to grasp the case for the police and prosecutors and is therefore unhelpful for the victims.

International legislations

Unfortunately, even foreign legal jurisprudence is weak. There are just a couple of countries which have formally passed a regulation on cyber flashing.

-

Singapore

Pursuant to Section 377BF(2) of the Singapore Penal Code, where any person is found guilty of cyber-flashing for the intent of obtaining sexual pleasure or causing embarrassment, alarm or pain to another person, he/she shall be punished with imprisonment for a period of up to one year, or with a fine, or both. If the perpetrator is below 14 years of age, harsher punishment is given. In January 2020, the city state declared cyberflashing as a criminal offence, with a year’s statutory penalty in jail. It was classified as an offence on account of emerging crime patterns causing cyber sexual harassment, the current felony is performed when an individual intentionally distributes a picture of their genitals to another person, expecting to see the image of the victim and that the perpetrator does it for the intent of gaining sexual pleasure or allowing the victim to feel humiliated.

Crucially, the crime is called “sexual exposure”. The Criminal Code Reform Committee noted that there were no sexual or malicious explanations for current crimes involving such types of disclosure, stating “nor did they catch the essence of the wrongdoing and were not characterised as a sexual violation”. This legislation includes numerous essential components that are worthy of being considered for the purpose of replicating. In terms of the photographs and images, it requires a representation of (A) the genitals of the suspect or (B) the genitals of another male, eliminating a burdensome demand for proof to show that the photograph is of the penis of the perpetrator. It is often a welcome acknowledgment of the essence of the trauma sustained by the survivor, since it does not matter if an image of the penis of the attacker or of another male is submitted to her. In comparison, rather than receipt, the crime is that of distribution; excluding any obligation to show that the photograph was obtained or seen by the perpetrator.

The evidence that the victim wishes to see a picture is dependent on physical exposure provisions developed to preclude unintentional genital exposure (as in a public bathroom). As far as the motivation criteria are concerned, the crime is at least wider than involving just signs of sexual pleasure, but it remains restricted. It prohibits cyberflashing instances that may be committed by other young people for the intent of satire, or as a prank. Overall this bill makes strong attempts to resolve the cyberflashing problem and introduces a provision that is appropriate to address the issue.

-

Scotland

The “Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act, 2009” criminalises coercion of an individual to look at a sexual image (Section 6). The original idea behind implementing the provision was to combat the extent and existence of sexual offending so as to incorporate as many eventualities as practicable, were protected by legislation. It is now used for the investigation of cyberflashing. Crucially, cyberflashing is classified as a sexual crime in this law and the possible punishments are substantial, including a cumulative period of incarceration of ten years. After the Scottish Law Commission (“SLC”) recognized the sexual crime of ‘causing an individual to participate in sexual intercourse’ in English law (S. 4, Sexual Offences Act, 2003), the amendment was implemented in the 2009 Act. It was a well accepted fact In Scotland and English law that sexual offending, described as ‘coercive’ by the Scottish Law Tribunal, could entail non-contact practices and actions.

The SLC acknowledged, however, that manipulative and offending conduct is more nuanced and diverse since it requires the usage of photographs and written documents, whereas English law merely allows for the crime of forcing someone to participate in sexual intercourse. It observed that “just as being compelled to indulge in sexual activity is a violation of the sexual autonomy of an individual, so is being forced to witness such activity”. Accordingly, the Law Council proposed that sexual communication without consent be introduced as an offence. It also observed that while English law had violations concerning the presence of a child in sexual conduct and induced a child to watch sexual activity, all of these offences were specific exclusively to children and sexual gratification were a prerequisite. Both limits were dismissed by the SLC as being excessively constraining and not including all forms of criminal conduct.

The consequence was section 6 of the “Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act, 2009” which established the crime of coercion of an individual to look at a sexual image to cover adults and children. The crime is that of deliberately forcing someone to look at a sexual picture while not having their permission. Unfortunately, this provision doesn’t encompass the scope of what is implied by the Law Committee, since the action that has to be displayed is to ’cause’ someone to look at a pornographic picture without their permission, rather than to share or convey the image. For e.g., if the perpetrator does not see the photograph, the offence is not recognized. It is often important to show clear motivations, as this at least involves shaming, distressing or disturbing the victim. Nevertheless, ‘sexual picture’ is narrowly defined, covering photos of the perpetrator, someone or an ‘imaginary person’ of the genitals or any ‘sexual behaviour.’ Therefore, this clause goes beyond cyberflashing to cover photographs, as well as false and photoshopped images, of other sexual conduct.

This study of Scots law has many things to be learnt. Framing a sexual crime ensures that the essence and harmful effects of the behaviour are properly understood and the interests of those people whose sexual liberty has been abused are acknowledged in applying to adults and adolescents. In comparison, this rule was not first enforced in the context of cyberflashing, but focused on the broad variety of forms in which sexual harm is committed in such a manner that the range of photographs protected is not unduly narrow. This illustrates the value of seeking to ‘future-proof’ the legislation as far as possible. In comparison, nowadays, the scope of ‘imaginary’ entities has special resonance and importance, as technology allows it possible to exploit and manipulate false photos and videos.

To address cyberflashing, strict regulation has been passed, the application of which has proved profound: the more general focus on violent and non-consensual activity has lead to the drafting of a restricted provision that can be used in increasingly changing contexts, such as the technical transition that has allowed cyberflashing. For these purposes, the legislation is broader than merely protecting a single genital image; the reach covers depictions of all types of sexual intercourse, which implies that it includes forcing an individual to look at pornographic images without their permission. Nevertheless, the rule is restricted to applying only if the perpetrator has caused the picture to be seen by another.

-

United States of America

In 2019, the first US state to bring out a legislation criminalising cyber flashing was enacted in Texas. “Section 21.19” of the “Texas Penal Code” deals with the “Unlawful Electronic Transmission of Sexually Explicit Visual Material”. An individual commits an offence if the person intentionally transmits graphic content through electronic means showing another person involved in pornographic activity or shown to the private sections of the person; or covers a male person’s genitals that are in a discernibly turgid state; and is unsolicited and transmitted without the receiver’s explicit consent. A crime is held to be a Class C Misdemeanour in this clause. The law’s sponsors concluded that while the new law addresses the physical act of indecent exposure, it remains silent on the concept of cyberflashing. The aim of the law was to give a strong disincentive to all those who even consider this and related improper actions. Thus, there has been a statutory act of “Unlawful electronic transmission of sexually explicit visual material” since September 2019, imposing a maximum penalty of a $500 payment under the Penal Code on sexual offences.

The offence is that of understanding the dissemination of graphic content showing photographs of some individual involved in sexual activity, the private parts of an uncovered person, as well as a male person’s concealed genitals that are in a discernibly turgid condition. This wide provision ensures that it contains not only depictions of male genitalia, but also of other types of sexual conduct. The dissemination of the pornographic images must have been done without any direct consent of the victim. The mens rea is clear in involving just deliberate dissemination without the sexual image’s approval. Consequently, under this clause, there is no clear motive criterion.

Nearly all cases of cyberflashing would be protected by Texan legislation since it is not limited in terms of intent, is a dissemination crime, and includes a broad variety of files. It is this aspect that makes this provision particularly captivating. The general concept of sexually pornographic graphic content suggests that, in essence, the clause becomes an offence for the sending of pornography without permission. In terms of regulation and debates over overcriminalisation, this could well contribute to problems b But it should be stressed that this is a sexual assault crime under which it has long been accepted that unwanted obscene shows represent a hazardous atmosphere.

Similar legislation amendments are currently being considered following the Texan lead in the state of California, where what is recognised as the “FLASH Act (Forbid Indecent Conduct and Sexual Harassment)” was passed in February 2020. In case of a first-time offence, the offence provides for a total punishment of $500, increasing to $1000 thereafter, if a person sends unsolicited or sexually suggestive content through electronic medium knowingly. Although the earlier iteration of this law only contained photographs of the penis of the suspect, the new proposal contains pictures of different types, including any person’s ‘exposed genitals or anus’. The Californian version offers interesting possibilities for clarifying consent conditions as far as permission is concerned. The latest proposal applies to the necessity to have “the photograph specifically requested” or that the victim “has not explicitly consented to its delivery” and this is explained to be met if “the submission or permission is conveyed in written, including, though not limited to, electronically communicated documentation”.

For a variety of factors, these proposed amendments are interesting. Firstly, there is a strong emphasis on sexual assault and its relationship to physical touch. Therefore, the offence is specifically framed as a matter of women’s harassment and the need for the law to keep up with technical advances. Over and above the paradigmatic manifestations of public transit abuse, the emphasis is now on all aspects of cyberflashing, including dating applications and all forms of social networking. The photos used are broad, but not as detailed as Texas, with clear requirements to prove consent and no requirement for motive. Because of these requirements, prosecution for this offence is probable, pursuant to some other clauses.

-

United Kingdom

The Law Commission, an autonomous regulatory agency charged with providing equal and current English and Welsh law, has now reached the consultation process of the Communications Offense Overhaul. The change is important to shield victims from negative online behaviour, including cyber-flashing, offensive comments and pile-on abuse, the Law Commission said.

While current legislation renders sending highly offensive or indecent messages an offence, they overlap with each other and struggle to explain what such words mean in the era of smartphones. Neither should they make it obvious, the Law Commission said, whether an abusive contact becomes grossly so, sufficiently to make it a criminal offence.

The Law Commission noted that new protections have struggled to keep up with improvements to how we interact today, over-criminalizing in some cases and under-criminalizing in others. These forms of cases are not properly handled by cyber harassment protected under existing communications crimes, the independent body added. The Commission recommends reforms to the Malicious Communications Act, 1988 and the Communications Act, 2003 to criminalise behaviour where a contact will “probably cause harm,” covering electronic attacks such as an obscene text, a social networking posting, a WhatsApp response, or Bluetooth-sent material. Meanwhile, under Section 66 of the “Sexual Crimes Act 2003”, cyber flashing is proposed to be used as a sexual crime.

In the meantime, these crimes specifically refer to minors under the age of 16, which can include for extra safeguards. In order to target sexual grooming, particularly the preparatory steps prior to some physical sexual offences, the offences of “causing a child to watch a sexual act” (sec 12) and “sexual communication with a child” (Sec 15A) were added. The finding in Sec 12, though, may be of ‘sexual conduct’ and it is not certain if this would apply to a male genital picture. The spectrum of Sec 15A is larger, with all penis representations most likely to be addressed by ‘sexual contact’. It is at least clear that the crimes are applicable to online activity.

Policy choices for legal reforms

Drafting of a special law that classifies cyberflashing as a crime. In consideration with the harms and impacts suffered by victim survivors, it is therefore recommended that a fresh legislation is enacted that will offer a strong ground for convictions and victim remedy.

-

As a sexual crime

In Singapore, Texas and Scotland, the crucial aspect in each of them is they classify the act of cyberflashing as a sexual crime and misconduct implying that the perspectives of victim-survivors are adequately understood and determines the essence and severity of the crime. It is therefore important for the creation of effective programmes for prevention and education. In comparison, characterization as a sexual crime ensures important safeguards for those who are victims and witnesses, such as universal complainant confidentiality and specific judicial protections.

-

Categorise transmission as an offence

Two contrasting approaches emerge: the first one is the Scotland approach that accepts a crime on causing the person to see the picture, the second being the delivery focus of Singapore and Texas. The Scottish approach is more complicated in that it requires not only establishing that the photograph was published, but that it was then subsequently seen. In these situations, the more convenience in dissemination will be desired to prevent the evidential burden on prosecutors and the victim-survivor.

-

Dissemination without Approval

The fundamental immoral is non-consensual behaviour, and if a clause requires that the delivery is without victim-survivor permission, it must contain non-consensual conduct. The main question then becomes the determination of what constitutes approval. The most direct solution will be to introduce the definition of consent. The interpretation has, however, been widely criticised as ambiguous and unhelpful. In all online harassment and intimidation cases, what is key is that agreement is not inferred or presumed. Explicit permission, however, may be used as a prerequisite, such as the ‘express consent’ required under Texan statute. In comparison, steps such as those suggested in California, where existing plans are that permission to accept photos and videos must be granted in written form, may be taken into account.

-

Intend that the witness could see the picture

Singaporean law notes that to avoid criminalising accidental transmission of photographs, the perpetrator should have meant that the victim saw the picture. The test case indicates that if the accused intended to send the picture to A, but actually forwarded the photo to B, the crime would not have been committed, because the accused did not expect B to see the photo. Since B could well be affected by those who are sending obscene pictures without consent, there can be no intent or “guilty mind” on the part of the sender. As a result, it is not necessary to institute criminal prosecution.

-

No criterion for proving clear motivations

The key wrong in cyberflashing is the emphasised of Texan law: non-consensual activity that interferes with the right of a person to sexual autonomy and dignity. Therefore, the crime is not defined as one performed just for personal purposes, as though the loss suffered is minimised by being cyber flashed for reasons of status-building or amusement. Therefore, this strategy ideally means that all aspects of cyberflashing are protected, the perspectives of the victim are properly acknowledged, and makes for the most logical prosecutions. Investigations and complaints to the police are inhibited by the need to show purpose to inflict distress.

However, if motivational conditions are to be included, they can, as in the applicable Scots and Singaporean rules, at least include both sexual pleasure and causing pain, discomfort or embarrassment. Furthermore, if careless intent is seen, this threshold should be reached, as in the Scottish legislation on non-consensual sharing of intimate photographs. This will seek to guarantee that understanding that the conduct might trigger distress to the survivor, even though not his actual motivation, would be adequate to fulfil the clause if, for example, a criminal is behaving in order to please or humour his mates.

-

Not Restricted to Genital Pictures of only the Accused

If the crime is confined to merely covering photos of the genitals of the accused, it would lead to an offence that is potentially difficult to prove. It will be important for police and prosecution to show that the offensive picture was of the genitals of the accused, which poses a multitude of issues, including a probable unattainable evidential burden, especially since the existing state and reach of forensic penile detection is restricted and inadequate for a criminal justice context. It is therefore not impossible to foresee that such a requirement would render the victim-survivors less likely to disclose the incident and the police less inclined to prosecute. Lawmakers should be ready to adopt the lead of other jurisdictions explicitly and include all pictures of the genitals.

-

Imaginary Characters and False Photos

Scottish legislation by specifying that the pornographic picture will be of the accused, another person or an “imaginary object” by forcing someone to look at a sexual image, guarantees broad applicability. Similarly, the legislation clarifies that for non-consensual distribution of intimate photographs encompasses photos manipulated by visual or other means, which means that photos and videos modified by technology are covered. These provisions mean that modern technology maintains pace with the legislation, making it accessible and simpler to produce photographs where it is almost difficult to know whether they are ‘true’ or ‘false’.

-

Criminalizing non-consensual pornographic picture dissemination

A penultimate element to address is whether to include material other than genital images. In the United States, for instance, as with Scottish legislation, many of the proposals and regulations apply to a wide variety of depictions of sexual intercourse, as well as images of genitals. In practice, certain laws form an offence of non-consential dissemination of pornography. The value of such scope is that it means that a country does not end up implementing a legislation that involves transmitting pictures of the penis without permission, just to discover the offenders begin to harass and violate using other kinds of photographs. It would also ensure that cyberflashing amongst other types of sexual harassment are linked to others. However, instead of merely creating a vague definition of a cyberflashing crime, it may be more useful for future-proofing the legislation against the various, ever-evolving actions of people who sexually harass and exploit other people, to create regulations to address the underlying wrong of sexual harassment.

Suggestions

In order to criminalise ‘image-based sexual harassment,’ covering any non-consensual dissemination and production of overt sexual material, obscene content, including updated photographs and threat communications, the government could enact an update to the Information Technology Act, 2000. They can also compensate for the complainant’s privacy and the cyber flashing legislation must be rendered gender-neutral as the case is with many other Indian cyber laws. It’s not shocking that very few of us feel secure in reporting cyber-flashing to the police owing to the existing uncertainties around the rules. For one instance, it is unknown whether or not cyber-flashing represents a crime in the same manner as flashing in real life does.

In reality, there’s the issue around recognition; who exactly is it that sent these images? They are almost always unannounced, confidential and absolutely difficult to differentiate from the identification of an individual. The often evolving forms in which we use technology to connect have a significant effect on our lives and that of the family. Getting a law that penalises cyber flashing will prevent potential criminals, thus opening a path for all to build a healthy and stable online forum. Special provisions will also function as a mechanism for victims to track cyber flash events and provide the police with a system for coping with those crimes. Training and awareness needed by police officers and other partners should also be done to further appreciate the situation. Offline, flashing is unconstitutional, and the same should not be allowed online.

Conclusion

The criminal justice system is failing victims of cyberflashing with no standard way to investigate online attacks. The legislation struggles to take into consideration the extremely prevalent ways of coercive sexual interaction women undergo. As for so many accidents sustained mostly by women, cyberflashing slips between the cracks and divisions of the Law. These interactions, as with other types of violence that have thrived with the advancement of technology, such as modes of image-based sexual assault such as ‘upskirting’ and the non-consensual sharing of sexual images, contradict defined definitions and raise a headache for victims and law enforcement in seeking to fit them into current legislation. Partly, this is because technology is progressing and offenders are developing different methods to threaten and exploit women, with the legislation often unable to keep up. Yet this is not the tale in its entirety. Lawyers have long argued that the statute fails to recognise and represent the expectations of women’s hurt, with some researchers developing entirely new ways of categorising and analysing the law with the perspectives of women at the forefront.

The dilemma is that while it is right to recognise that there are ‘no clearly defined and independent empirical classes’ into which ‘men’s acts can be placed,’ in order to provide a criminal law solution, we must strive to organise the law in such a way that it reflects, supports, and then challenges the harms experienced by women and other segments of society impacted by the same. The implementation of a new legislation criminalising cyberflashing is a first move in remediating this condition. This tactic has several benefits, such that the actions are obviously illegal, leveraging the criminal law’s descriptive ability to signal to the community that this is unwelcome and inappropriate conduct. In this way, by acknowledging cyberflashing as a form of sexual assault and violence, every new legislation can promote educational and other preventive initiatives. In addition, indictment and prosecutions will encourage certain claimants to secure some degree of compensation for the trauma they have endured.

Nevertheless, though welcome, the pitfalls to a particular statute that only involves cyberflashing are that it will offer a solution for defined activities in the short-term, but the law would not ‘future-proof’ to protect the new, though yet unthinkable, avenues in which perpetrators would eventually perpetrate violence and harassment. a.Therefore, as well as introducing a single measure, legislation that criminalises broader forms of sexual abuse that may provide more general security from coercion in the longer run must also be considered.

References

Articles, research papers, etc.

- Ahmed, Aryan. “Cyber-Flashing: What Are The Legal Options Available To Victims Of This New-Age Form Of Cyber Sexual Harassment?” Bar And Bench – Indian Legal News, 6 May 2020, https://www.barandbench.com/amp/story/apprentice-lawyer/cyber-flashing-a-new-age-form-of-cyber-sexual-harassment-and-what-are-the-legal-options-available-to-victims.

- McGlynn, Clare, and Kelly Johnson. “Criminalising Cyberflashing: Options for Law Reform.” The Journal of Criminal Law, Nov. 2020, p. 002201832097230. SAGE Publications, doi:10.1177/0022018320972306.

- Moss, Rachel. Cyber Flashing And Abusive Messages Could Soon Become Criminal Offences. 11 Sept. 2020, https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/cyber-flashing-could-soon-become-a-criminal-offence-about-time_uk_5f5b34efc5b62874bc1b62c9?guccounter=1.

- Pandia, Shivangi. “Stranger Danger: Making A Case For Cyber Flashing As A Crime.” The Criminal Law Blog, 3 June 2020, https://criminallawstudiesnluj.wordpress.com/2020/06/03/stranger-danger-making-a-case-for-cyber-flashing-as-a-crime/amp/.

- Reuters. “Cyber-Flashing: New Way To Harass Women – Times Of India.” The India Times, 29 Feb. 2020, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/uk/cyber-flashing-new-way-to-harass-women/articleshow/74410290.cms.

- Winder, Davey. “Smartphone Abusers Your Time Is Up: Cyber-Flashing To Become A Sex Crime.” Forbes, 13 Sept. 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/daveywinder/2020/09/13/smartphone-perverts-your-time-is-up-cyber-flashing-to-become-a-sex-crime/?sh=273567736e0b.

Legislations

- IT ACT, 2000

- Sexual Crimes Act, 2003

- Texas Penal Code

- Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act, 2009

- Singapore Penal Code

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skill.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications