This article is written by Vedant Saxena, from Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Punjab. This is an exhaustive article that analyzes the wrong of nuisance, both as a crime and a tort.

Table of Contents

Introduction

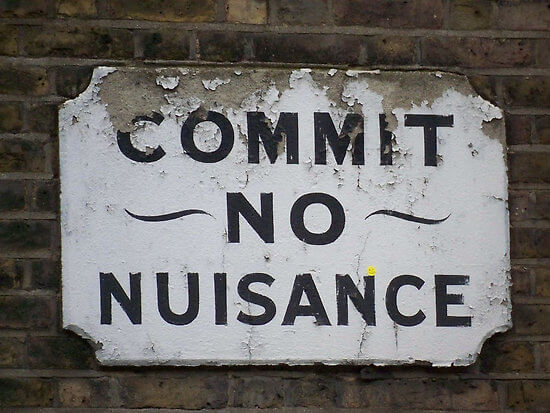

The word “nuisance” has come up from the French word “nuire”, which means “to do hurt, or to annoy”. Every person is entitled to the peaceful possession of his property. Any element of disturbance or hindrance in the enjoyment of property rights would constitute a nuisance. According to Stephen, any act that causes annoyance or injury to the defendant, concerning his enjoyment of his property, and which does not constitute trespass, is a nuisance. According to Salmond, an act that involves an unlawful release of an object into the plaintiff’s premises, which is deleterious to the plaintiff’s general well-being, is a nuisance.

What is Nuisance?

Nuisance could be defined as unlawful interference in the peaceful enjoyment of one’s property, or any right associated with it. There is a significant difference between trespass and nuisance. In the former, there occurs a physical interference in the plaintiff’s possession of the land. Whereas in latter, there is more of an indirect interference with the plaintiff’s right to property. For instance, flinging pebbles at the plaintiff’s property would constitute trespass, whereas hindering the plaintiff’s peaceful possession of the property by playing your radio at an unusually high volume would result in a nuisance. Nuisance could occur either with respect to a particular individual’s property rights or in the context of the general public’s property rights.

Public Nuisance

Section 3(48) of the General Clauses Act, 1897 declares public nuisance to be as defined by the Indian Penal Code. According to Section 268 of the Indian Penal Code, public nuisance comes into the picture when a person commits an act that causes common injury, danger, or annoyance to the general public. Basically, any act that hinders either the property rights of the general public or any other right. For instance, in Malton Board of Health v. Malton Manure Co., (1879), it was declared that carrying on a trade/business that causes deafening noises is impermissible, as it would cause a public nuisance. In order to avoid multiplicity of proceedings, a public nuisance is unconcerned with individual rights. However, a person could sue the wrongdoer in his private capacity, if the following conditions are satisfied-

- The person needs to show that the injury he faced was substantially greater than what the rest of the public faced.

- The injury he faced must essentially have been direct, not merely consequential.

Nuisance as a crime

Public nuisance has been declared a crime under Section 268 of the Indian Penal Code. Public nuisance occurs when a person commits an act that causes annoyance, or injures or threatens to injure the rights of the general public, with respect to health, safety, morals, convenience, or welfare of the general public. Basically, an act done to the detriment of the public, or an omission when the act was necessary for the public good, would constitute a public nuisance. Examples include blocking a public road, unlawfully digging up a pit on public grounds, exploding fireworks on the streets, operating a house of prostitution, harbouring vicious dogs, and unlicensed prizefights.

In Leanse v. Egerton, the plaintiff, while passing by the defendant’s unoccupied premises, was struck by a piece of glass that fell out of a broken window. An air raid on a Friday had caused the shattering of the window. It was held that although the defendant’s offices were shut every Saturday and Sunday due to the difficulty in finding labour on these days, the defendant’s agents ought to have inspected the premises and taken reasonable steps to prevent such mishaps. Therefore, they were held liable for committing public nuisance, since their act injured or threatened to injure the rights of the general public.

In K Ramakrishnan v. State of Kerala (1999), the court declared public smoking of tobacco in any form to constitute a public nuisance. Smoking is harmful to the public at large, thereby fulfilling the requisites of public nuisance.

In Soltau v. De Held (1851), the plaintiff resided in close quarters to the roman catholic church. The chapel bell of the church was rung all through day and night. It was held that the continuous ringing of the bells constituted a public nuisance.

Punishment in public nuisance

Section 290 of the Indian Penal Code deals with the punishment attracted by an act of public nuisance. According to it, any person guilty of committing public nuisance is to be punished with a fine which may extend up to 200 rupees. However, Section 291 says that if an injunction has been delivered against the defendant, and he still does not cease the act of nuisance, he would either be punished for a term of imprisonment that may extend up to 6 months, or be charged a fine, or both.

Private Nuisance

When there is an unlawful interference with respect to a particular individual’s property rights, the act constitutes a private nuisance. Thus, for private nuisance to occur, the following two conditions must be satisfied-

- There must be an interference with the ‘peaceful possession’ of the plaintiff’s property.

- The interference must be unlawful, i.e., it must not satisfy any of the defences to the tort of nuisance.

A private nuisance may occur in two modes. The first one is an injury to the plaintiff’s property, and the second one being physical discomfort.

- Injury to property

In St. Helen’s Smelting Co. v. Tipping (1865), the plaintiff’s land was in close quarters to a copper smelting factory, which had been operating for quite some time then. As a part of its regular procedure, the factory emitted large quantities of noxious gases. The emission caused substantial damage to a large number of trees on the plaintiff’s land. It was held that although the defendant had lawfully been operating his business for a substantial amount of time, and the plaintiff himself had come to the place of the nuisance, the claim was allowed. No matter how reputed a trade/business is or how long it has been operating, if an individual does incur physical discomfort or injury to his property, he could sue for private nuisance.

In Hollywood Silver Fox Farm Ltd. v. Emmett (1936), the plaintiff carried on a business of breeding silver foxes in order to utilize their fur. Foxes are, by their very nature, of a nervous temperament, and sudden scares could cause them to miscarry. The defendant, an animal rights activist, lived adjacent to the plaintiff’s land. He did not approve of the plaintiff’s business and sought to have it terminated. He wilfully asked his son to fire a gun in order to startle the foxes, and thus cause them to miscarry. The plaintiff sought an injunction in order to prevent the defendant from committing this act. His claim was allowed since the defendant’s act involved injury to the plaintiff’s property.

In Ram Raj Singh v. Babulal, the defendant carried on a trade that involved crushing bricks through a brick crusher apparatus. The process resulted in the emission of a large quantity of dust in the surrounding areas. The plaintiff, a medical practitioner, lived adjacent to the defendant’s premises. He complained that the dust emitted as a result of the plaintiff’s trade was detrimental to his and his patient’s health. In this case, since a large number of people were involved, the plaintiff’s act constituted a public nuisance. However, the court issued an injunction order against the defendant and granted special damages to the plaintiff.

- Physical discomfort

In order to satisfy this essential, the following two conditions must be followed-

- The act must not be within the defendant’s usual course of enjoyment of his property. In order to constitute an act of nuisance, the defendant must have committed an act outside the purview of his ordinary enjoyment of land.

- The act must cause physical/mental discomfort to an ordinary person in the locality.

In Imperial Gas Light and Coke v. Broadbent, the defendants were involved in a manufacturing business that emitted large quantities of noxious gasses. The plaintiff’s residence in close quarters to the defendant’s business premises. The plaintiff complained that the residual gases had caused substantial damage to his trees and plants. Although he was awarded damages, the defendants did not cease the act of nuisance. In a subsequent suit, the plaintiff managed to secure an injunction prohibiting the defendants from continuing the act.

In Inglis v. Shots Iron Co., the defendants carried on a business that involved calcining coal and ironstone. The plaintiff complained that the noxious vapours emitted from the defendants’ trade caused him physical discomfort, and also caused significant damage to his tree plantations. His appeal was granted.

Defences

-

Prescriptive rights

An unlawful interference in the peaceful possession of the property would constitute a private nuisance. However, the defendant could acquire the right to commit the nuisance, in the event of the plaintiff not taking any steps to stop the defendant from committing the act of nuisance. In such cases, the act of nuisance gets legalized ab initio, i.e, it is presumed that the plaintiff consented to it at its very commencement. However, no prescriptive rights could be acquired in cases of public nuisance, since public nuisance is a crime and thus prohibited by law.

In Sturges v. Bridgman, the plaintiff was a doctor who came to occupy a piece of land. Further, he bought a shed from where he would carry on his business. The shed happened to be in close quarters to a confectioner’s property. The doctor claimed that the confectioner’s act of grinding his pestle and mortar was extremely noisy, and thus an interference in the peaceful enjoyment of his property. It was held that although the defendant had been using machinery for more than 20 years, the plaintiff was not affected by the noises until he started working in the shed. Thus, what constitutes a nuisance is to be assessed on a case by case basis.

-

Statutory Authority

For an act to come under the ambit of nuisance, it must essentially have been committed ‘unlawfully’. An act committed by a person fulfilling the duty imposed upon him by the state is considered lawful, and thus, not nuisance. In Vaughan v. the Taff Vale Railway Company, the defendant had been authorised under a statute to run locomotives. The defendant’s railway was adjacent to a wood, which harboured inflammable grass. On account of the sparks emitted by the locomotives, the wood was burned down. It was held that the defendant had not committed an act of nuisance, since a statute had granted him the authority to commit the act.

Remedies

The most common way to remedy nuisance is monetary compensation. The object of providing damages is to place the plaintiff in the same position as he was prior to the act of nuisance. However, the plaintiff may also file for an injunction against the tortfeasor. An injunction, also known as a restraint order, is a command by the court either prohibiting the plaintiff from committing the wrongful act (prohibitive injunction) or ordering the plaintiff to do something in order to cease the wrongful act (mandatory injunction).

Conclusion

Public nuisance has been declared a crime under Section 268 of the Indian Penal Code. It attracts a penalty of a fine which may extend up to 200 rupees. In the event of the defendant continuing the act in spite of being enjoined by a lawful authority not to, he would be punished for a term of imprisonment that may extend up to 6 months, or with fine, or both (Section 291).

Since tort law is uncodified in the Indian legal system, what constitutes private nuisance is decided on a case by case basis. The Indian courts have also borrowed a number of English law principles, as well as court decisions from the common law system in order to help them assess cases of private nuisance.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications