This article has been written by Lyngeolle Morris, pursuing a Certificate Course in Intellectual Property Law and Prosecution from LawSikho.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The patent law system in India has undergone significant changes and amendments since the country’s incorporation of the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (‘WTO’s TRIPS Agreement, ‘TRIPS Agreement’ or ‘the Agreement’). The TRIPS Agreement became effective on 1 January 1995. The overarching aim of the TRIPS Agreement is to provide the appropriate standards and means for the use and enforcement of trade-related intellectual property rights (Article 1, TRIPS agreement) and the agreement has been considered the “most comprehensive multilateral agreement on intellectual property” (World Trade Organization, n.d).

While the agreement came into force in 1995, developing countries at the time such as India were given a ‘grace period of four years or up to 1 January 2000 to apply the Agreement within its domestic legal system, save Articles 3 – 5 of the Agreement. (World Trade Organization, 2021). Despite this, several changes have been made to India’s patent regime even beyond this transition period. For the purposes of this article, reference will be made to the amendments made to India’s Patents Act in 1999, 2002, and 2005.

To better understand whether India’s patent laws are in compliance with the TRIPS Agreement, I will firstly explore the theoretical concepts of monism and dualism in interpreting the relationship between India’s Patent system on a domestic level and the international legal regime as set out under the WTO’s TRIPS Agreement. Next, I will delve into the progression of India’s patent law regime following the incorporation of the TRIPS Agreement. Further, I will consider some case studies which will help to determine some of the underlying reasons behind India’s ‘non-compliance or ‘slow compliance’ with the TRIPS Agreement by looking into how India’s history, attitudes, and cultural norms play a role in the question of compliance. Finally, I will explore the ways in which India has built a sophisticated patent regime system post-TRIPS and how it can endeavor towards greater compliance with the TRIPS Agreement in the future while also balancing its own national interests.

Compliance in international law: understanding perspectives of monism and dualism in India

It is a fundamental principle of international law that when a State Party becomes a signatory to an international treaty, it should endeavor to incorporate the treaty into its domestic legal system, with the view of ensuring that there are no inconsistencies between the two. International treaties contain an article or clause which requires a State Party to refrain from any acts that would be in contravention of the Treaty’s object and purpose. This principle is enshrined in Article 18 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (‘the Vienna Convention).

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights encompasses this principle in Article 1 of the Agreement. Under the TRIPS Agreement, there is a generous wording of the incorporation of the TRIPS Agreement and indicates that State Parties “…may, but shall not be obliged to, implement in their law more extensive protection than is required” and further that State Parties shall have freedom to “…determine the appropriate method” in its implementation of the TRIPS Agreement.

However, the TRIPS Agreement contains a proviso that notwithstanding, the domestic legal system should “…not contravene the provisions” of the TRIPS Agreement (Article 1, TRIPS Agreement). Similarly, Article 18 of the Vienna Convention provides that a party to a treaty has an obligation to refrain from engaging in conduct that would amount to defeating the object and purpose of the treaty prior to its entry into force.

Monistic perspective vs dualistic perspective

There has been exhaustive academic debate on whether the international and domestic legal system comprises one system under the perspective of monism or whether the international legal system and domestic legal system constitute separate systems, under the dualism principle (see Nijman, J. & Nollkaemper, A., 2007).

According to monist defenders, the law is to be considered as a unity and can only be deemed as deriving from one common source. As such, under the monistic perspective, the international legal regime is to be deemed as forming part of domestic law (Gragl, 2018) and therefore a treaty may become operative once the State party has entered it into force and it is in accordance with the constitution (Aust, 2013). On the other hand, defenders of dualism posit that while a State party may respect international law, it must individually incorporate and sanction it within its own domestic legal regime by implementing legislation to that effect (Jyawickrama, 2009).

Chandra (2017) argues that while formally, India is deemed as a dualist state, in reality, it exhibits various monistic tendencies, based on its relationship with the power of the Executive in assuming international obligations without seeking Parliamentary approval in some instances, Parliament in its power to pass a law to reflect objectives of international law and the judiciary in interpreting and enforcing international law through the courts.

In light of the backdrop of this dualist-monist dichotomy, I will explore the changes over the years in India’s domestic law since the incorporation of the TRIPS Agreement.

India’s incorporation of the TRIPS Agreement

According to the World Trade Organization, with effect from 1 January 1995, India became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and became a party to the TRIPS Agreement. This was met with much debate and opposition, as it took the stance during the negotiations that IPR protection was specifically within the purview of the World Intellectual Property Organization and not the WTO (Unni, 2012). India argued during the negotiations that a country’s economic development should be taken into consideration when determining the extent of patent protection required, and therefore was a leading advocate on behalf of developing countries for the transition period approach as it relates to compliance with TRIPS (Foster, 1998). After the adoption of the TRIPS Agreement, India had undergone amendments to the Patents Act of 1970 (‘the 1970 Act’ or ‘the Principal Act’), culminating in the Patents (Amendment) Act, 1999 (‘the 1999 Act’, the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2002 (‘the 2002 Act’) and the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005 (‘the 2005 Act’).

Progression of India’s patent law regime after the incorporation of TRIPS Agreement

Post-TRIPS and the Patents (Amendment) Act, 1999

After the adoption of TRIPS, India was faced with two main issues that resulted in its amendment to the 1970 Act. These were that firstly, India needed the means to facilitate pharmaceutical and agricultural chemical product applications, also known as a ‘mailbox’ facility, and to have filing dates assigned to each application filed (see Article 70.8, TRIPS Agreement). Secondly, under the TRIPS agreement, it was required that India provide for exclusive marketing rights (EMRs) in the instance of certain mailbox applications (Article 70.9, TRIPS Agreement), that is, the exclusive rights to sell or distribute the substance covered in a patent or patent application in the particular country.

Notwithstanding that India had brought an Ordinance into effect on January 1, 1995, to provide for the mailbox facility and the protection of EMRs, it had failed to pass the requisite legislation before Parliament (Chaudhuri, 2005).

This act of non-compliance had consequences for India, as it resulted in the issue being addressed in the first case before the World Trade Organization’s Dispute Settlement Body in the well-known case of US v India (DS50) which commenced in 1996. The following documents relative to the case can be retrieved as follows:

- A summary of the complaint can be found here.

- The Consultation request by the United States can be found here.

- The Report of the WTO Dispute Panel can be found here.

- The Report of the WTO Appellate Body can be found here.

- The Status Report by India on the recommendations and rulings can be found here.

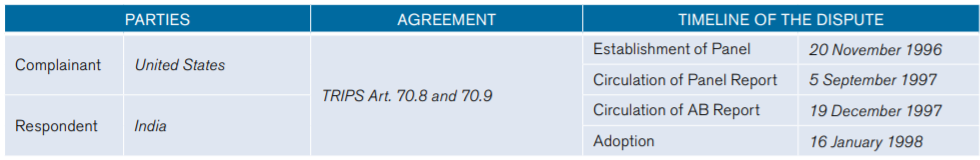

A summary of the parties, the contravened clauses, and the timeline of the dispute are summarized below.

(World Trade Organization – INDIA – PATENTS (US) (DS50), https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/1pagesum_e/ds50sum_e.pdf. Retrieved March 29th, 2021.

In this case, the United States brought a complaint against India before the World Dispute Settlement Body and raised the issues that India had failed to provide a mailbox facility and EMRs into its domestic law rendering India to be non-compliant with Articles 70.8 and 70.9 of the TRIPS Agreement.

The Panel found that India was in breach of the obligations pursuant to Articles 70.8(a) or Article 63(1) of the TRIPS Agreement since it had not provided the means of allowing a product patent for pharmaceutical and chemical inventions to preserve novelty and priority, and further did not provide a mechanism for the grant of EMRs (see Panel Report, 1997). India subsequently appealed the decision before the WTO’s Appellate Body, and the Appellate Body upheld the main findings of the Panel, concluding that India’s patent filing system had been inconsistent with the above-said Articles (see Appellate Body Report, 1999).

India then subsequently brought its patent filing system into conformity with Article 70.8 and 70.8 of the TRIPS agreement, resulting in the Patents (Amendment) Act, 1999 being passed by Parliament. (See India’s Status Report, 1999).

The Patents (Amendment) Act, 2002

The Patents (Amendment) Act, 2002 (‘2002 Act’) brought about a number of changes to the patent regime in India. Below, I will explore some of the amendments that were brought about to India’s patent system in the 2002 Act.

Term of the patent extended

The 2002 Act introduced a new patent term of twenty (20) years, bringing this section in compliance with Article 33 of the TRIPS Agreement, which provides that the patent term of protection should be available for a period of twenty years from the date of filing. Unni (2012) describes this as one of the “most significant” changes to the 1999 Act.

Previously the term of the patent for inventions related to the method or process of manufacturing a substance being used or capable of being used as a food, medicine or drug was five (5) years from the date of sealing the patent or seven (7) years from the date of the patent, whichever is shorter (Section 53 (1) of the Principal Act). For other inventions, the patent term was previously fourteen (14) years from the date of the patent (Section 53 (2) of the Principal Act).

Definition of “invention” and “inventive step” amended

Under section 2(1)(j) of the Principal Act, the term “invention” was defined as an art, process, method, manner, substance, the machine, apparatus, or another article which was new and useful. This definition was amended to “…a new product or process which involves an inventive step and has industrial application”. The definition was also extended to include an “inventive step”. (see Section 2 (j) and (ja), 2002 Act). These new additions are in keeping with the definitions found under Article 27.1 of the TRIPS Agreement.

Definition of patentable subject matter

The 2002 Act brought about wide-sweeping changes to the kinds of inventions that would be defined as patentable subject matter. Amendments were made to section 3 of the Principal Act in which a more comprehensive list of what would be excluded from patentability as set out.

For instance, those inventions contrary to public interest have been extended to include inventions that are contrary to public order or morality and which cause prejudice to humans, animals, and plants (see Section 3 (b) Principal Act, substituted by section 4 of the 2002 Act).

Some examples of the exclusions in the 2002 Act are outlined as follows:

- plants and animals other than micro-organisms;

- mathematical methods, business methods, computer programs, algorithms;

- scheme, rule, or method for performing a mental act or in respect of a game;

- presentation of information;

- topography of integrated circuits;

- traditional knowledge or traditional known components.

This section therefore significantly harmonized with Article 27.1 and Article 27.2 of the TRIPS Agreement.

Compulsory licensing framework

Amendments were also made to India’s compulsory licensing framework under the 2002 Act. According to the WTO compulsory licensing exists when a third party is granted permission by the government to utilize a patented invention without the prior consent or confirmation of the patent owner.

The 2002 Act was also modernized to reflect the provisions and spirit of TRIPS (see particularly Article 33, TRIPS Agreement), in which it set out three grounds under which a compulsory license would be granted (Sections 84(1)(a),(b),(b), 2002 Act) and the procedure to be applied where a compulsory license is being obtained (see Sections 84 -92 of the 2002 Act).

The 2002 amendment removed the concept of Licenses of Right which was previously found under section 86 of the Principal Act. Previously, a patent owner could apply to the Controller-General of Patents three years from the date of the patent grant, to have the patent in question made available to the public by having the patent endorsed with the term “license of right”.

The Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005

Patent Protection for pharmaceuticals, foods, agro-chemicals

Lee (2008) purports that perhaps one of the most significant changes under the Patent (Amendment) Act of 2005 was the extension of product patents to pharmaceutical substances. Previously, patents of this nature were not patentable, but this changed with the deletion of Section 5 of the Principal Act which previously provided that only the process or method of manufacturing such substances but not the substance themselves.

Other changes which were brought about by the 2005 Act were the definition of patentable subject matter and what is considered an inventive step. Of particular note is section 2 which was amended to qualify those discoveries of new forms of a known substance that would not be deemed patentable. The provision in the 2005 Act provides that such discoveries would only be those that “…result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance”. Unni (2012) notes that the intention of this amendment is to prevent frivolous applications where there are only minor modifications of known inventions.

The other change found in the 2005 Act is found in respect of the amended definition of an ‘inventive step’. The definition was extended to include a feature that includes some “technical advance” or having some “economic significance” or both (section 2 (j)(a)). This broadened definition tends to inculcate similar phrasing as found in Article 31(l)(i) of the TRIPS Agreement.

Pre-grant and post-grant opposition

Under the provisions of the 2005 Act, there are certain pre-grant and post-grant opposition procedures that are set out under the Act. Section 23 of the 2005 Act substitutes sections 25 and 26 of the Principal Act and sets out the mechanism in which an opponent can put forward an opposition either before or after the grant of a patent. The grounds for opposition proceedings as outlined under Sections 25(1) and 25(2) are brought before the Controller-General of Patents, who may then submit the notice of the proceedings to an Opposition Board.

In the instance of opposition procedures, the TRIPS Agreement sets out the principles to be considered in such administrative decision-making, noting that decisions should be fair, equitable, carried out without unreasonable delay or unnecessary complications or costs. It further provides that decisions are to be provided in writing with reasoning provided (see Articles 41.2, 41.3, 62.4).

As such, in remaining compliant with TRIPS, the opposition procedures should have consideration for these general guidelines.

According to a 2020 Report by India’s Office of the Controller-General of Patents, Designs & Trademarks (hereinafter ‘IP Office’), there has been substantial modernization of the infrastructure of the IP Office which has significantly impacted the work-flow and processing of applications filed. Of particular note is that the IP Office has reported that the time for final disposal of patent applications is projected to reduce to 24-30 months from the filing date by the end of the year 2021, in comparison to previous years where the average time frame had been about 48 months from filing. This time frame is likely to encompass instances where oppositions are being requested. It is therefore purported that the reported reduction in the time for disposal has been a key focus of India, in keeping with the general principles under TRIPS.

Compulsory licensing requirements

Another significant amendment has been in the area of compulsory licensing in the 2005 Act in which there has been the inclusion of compulsory licensing for the export of certain patented pharmaceutical products (insertion of Section 92A). These products relate specifically to exportation to countries that have either zero or insufficient manufacturing capacities for the product in question to address a public health problem. In such an instance, the license must have been granted by the receiving country or must have permitted the importation of the product from India (see Section 92A).

Judicial interpretation of compliance with the TRIPS Agreement

Novartis AG v. Union of India (2007)

The case of Novartis AG v. Union of India was the first instance in which questions regarding India’s compliance with the TRIPS Agreement were brought before the Indian courts. The complainant, in this case, was a Swiss pharmaceutical company, namely Novartis, which sought to patent a cancer drug called Glivec. However, after the Patent Office denied the application, the Complainant brought a claim before the Indian High Court of Madras, seeking a declaration that that Section 3(d) of the Patent Act of 1970 as substituted by the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005 was not in compliance with the TRIPS Agreement and/or that it was (unconstitutional) or arbitrary, illogical, vague and offends Article 14 of the Constitution of India.

In this case, the court found that it did not have jurisdiction to interfere with the laws of Parliament (see para. 7, para. 8) by testing the validity of the section as being incompatible with Article 27 of the TRIPS Agreement. The Court, in making reference to the case of State of A.P. Vs. Mc Dowell & Co. emphasized the position taken in this case that there is a presumption that Parliament is aware of the needs of the people and therefore is not in a position to make a judgment on the legislature (para. 17). It further reiterated the settled position held in that case that there were two instances in which a law by Parliament could be struck down, namely: lack of competence by the legislature and a violation of the Constitution (para.18). The court was of the view that Section 3(d) contained ‘built-in measures’ that would allow the statutory authority to be guided in the exercise of its power (para. 18). The court also found that there was no instance of a violation of Article 14 of the Constitution of India (para. 19).

Conclusion – is the patent law in India compliant?

Having undergone a multi-stage approach in becoming TRIPS-compliant, it is evident that India has endeavored over the years to bring its patent legal regime in alignment with the TRIPS Agreement.

On the other hand, it should be noted that pursuant to Article 1 of the TRIPS Agreement, countries, in general, have an express reservation regarding the method of implementation within their domestic legal regime. As such, there still leaves some ‘wiggle room’ for India to retain a discretionary approach in harmonizing the provisions of the TRIPS Agreement provided that the patent regime in India does not contravene the spirit of the TRIPS Agreement.

The early changes to the Principal Act following the case of US v India were a clear indication that India was prepared to ensure that its laws were in harmony with the TRIPS Agreement. Reichman (1998) suggests that it is hoped that the findings in the case of US v India would help to “cool passions” between the developing and developed countries in the short and medium terms. He further posits that the benefits, in the long run, would seek to drive an environment that is more competitive post-TRIPS resulting in investment and technological innovation that would be beneficial to all.

Many of the changes to India’s patent system have not been met with smooth transitions and this may be explained based upon the country’s political, economic, and socio-cultural reasons for ‘slow’ compliance. The outcome of Novartis AG v. Union of India shed light on the prevailing circumstances in India, in which the country had developed what Mueller (2007) describes as having developed a “world-class generic drug manufacturing industry” through its exclusion of pharmaceutical products from patent protection. The findings of the case also revealed the need to balance the interests and history of a country and those of the international legal regime. Having a large generic drug industry, meant that India was able to provide affordable medicine to its citizens (Lee, 2008). The decision in Novartis was evidence that member states under TRIPS maintain a certain level of flexibility in compliance, having consideration for the country’s unique social and economic circumstances.

The road ahead: India’s proposals for a TRIPS-compliant patent legal regime

Reichman (1998) suggests that while the TRIPS agreement may ultimately benefit developing countries through increased foreign investment, increased transfer of technology as well as drive local innovation, there will on the other hand be drawbacks in light of the high standards sets by the TRIPS Agreement such as the imposition of costs which will be required to obtain the tools and infrastructure need to bridge the technology ‘gap’ or standards.

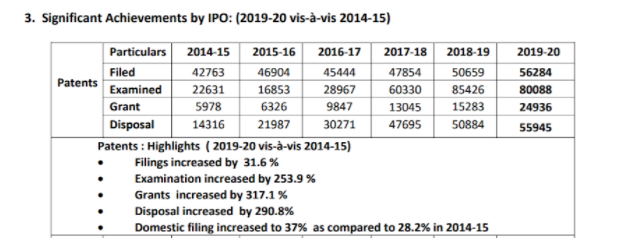

Since the incorporation of the TRIPS Agreement, India has embarked upon developing a sophisticated patent regime over the past few decades. Some of the country’s patent achievements can be seen below.

Source: ‘Summary of Achievements by Office of the CGPDTM (2014-15 to 2019-2020’ by the Office of the Controller-General of Patents, Designs, and Trademarks. 2020,18-8-2020_Achievements_of__CGPDTM_during_2014-15_to_2019-2020_and_Impact_of_steps_taken-converted.pdf (ipindia.gov.in).

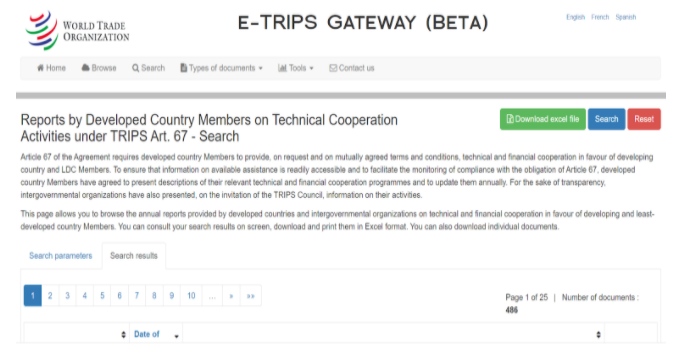

Furthermore, the country has modernized its IPR system by garnering support through obtaining technical assistance and cooperation from developed countries and intergovernmental organizations in light of Article 67 of the TRIPS Agreement which mandates that developed country Members are to provide technical and financial cooperation to help support developing and least-developed country Members.

Instances of such support can be found within the annual reports found at the E-Trips Gateway webpage: https://e-trips.wto.org/, a screenshot of which can be seen below.

Source: ‘Reports by Developed Country Members on Technical Cooperation Activities Under TRIPS Art. 67 – Search’’ by the World Trade Organization 2021, Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights – Search the Entire e-TRIPS Database (wto.org)

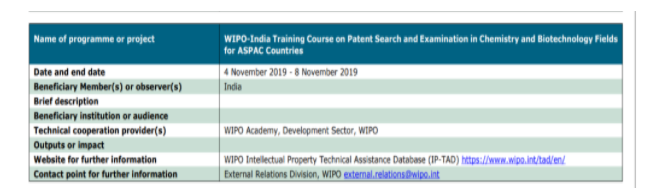

Some of the activities which have been spearheaded by the World Intellectual Property Organization (‘WIPO’) would also prove useful in keeping with the WIPO-WTO Cooperation Agreement as part of a general initiative to harmonize intellectual property into the country’s national development policy and framework.

One of the projects conducted by WIPO in November 2019 is listed below and encompasses one of the many other initiatives which have taken place to engage in a collaborative and consultative approach of which India was a beneficiary.

In the final analysis, it is purported that the patent regime in India has been significantly transformed over the years since the incorporation of the TRIPS Agreement and has done so while also balancing its own national interests and needs. In the future, as the country continues to gain technical assistance and cooperation through education, training, and infrastructural development, it is inevitable that the country will have a more robust patent regime in years to come. It will therefore be critical for the country to ensure that the kinds of assistance it will receive moving forward are related to the specific technical areas where such assistance is appropriate so as to further propel the country’s patent system and ultimately to achieve the objectives under the TRIPS Agreement.

References

- Agreement Between WIPO and WTO, 22 December 1995, World Intellectual Property Organization-World Trade Organization, 35 I.L.M. 754 (1996), https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/wtowip_e.htm.Accessed 23 March 2021.

- The Patents Act, No. 39 of 1970, Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Department of Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade), India, 19th September 1970, https://www.advocatekhoj.com/library/bareacts/patents/index.php?Title=Patents%20Act,%201970. Accessed 17 April 2021.

- The Patents (Amendment) Act, 1999, No. 17 of 1999, Acts of Parliament, Ministry of Law, Justice and Company Affairs (Legislative Department), New Delhi, 26 March 1999/Chaitra 5, 1921 (Saka), https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/Portal/IPOAct/1_34_1_patents-amendment-act-1999.PDF. Accessed 17 April 2021.

- The Patents (Amendment) Act, 2002, Act No. 38 of 2002, Acts of Parliament, Ministry of Law, Justice and Company Affairs (Legislative Department), New Delhi, 25 June 2002/Asadha 4, 1924 (Saka), https://ipindia.gov.in/writereaddata/Portal/IPOAct/1_125_1_THE_G.AZETTE_OF_INDIA.pdf. Accessed 17 April 2021.

- The Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005, No. 15 of 2005. Ministry of Law and Justice (Legislative Department), New Delhi, 5 April 2005/Chaitra 15, 1926 (Saka), https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/in/in018en.pdf. Accessed 17 April 2021.

- TRIPS: Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Apr. 15, 1994, Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization, Annex 1C, 1869 U.N.T.S. 299, 33 I.L.M. 1197 (1994), https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips_01_e.htm. Accessed 23 March 2021.

- Chandra, Aparna. “India and international law: formal dualism, functional monism.” Indian Journal of International Law, 2017, vol. 57, pp. 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40901-017-0069-0.

- “Compulsory licensing of pharmaceuticals and TRIPS”. World Trade Organization, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/public_health_faq_e.htm. Accessed 29 March 2021.

- “DS50: India — Patent Protection for Pharmaceutical and Agricultural Chemical Products”. World Trade Organization, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds50_e.htm. Accessed 11 April 2021.

- “Frequently Asked Questions about TRIPS [ trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights in the WTO”. World Trade Organization http://www.wto.org/English/tratop_e/trips_e/tripfq_e.htm. Accessed 31 March 2021.

- “Overview: the TRIPS Agreement”. World Trade Organization, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/intel2_e.htm#patents. Accessed 23 March 2021.“Frequently Asked Questions about TRIPS [ trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights in the WTO”. World Trade Organization http://www.wto.org/English/tratop_e/trips_e/tripfq_e.htm.

- Economic Law, 1998, vol. 1, issue 4, pp. 585-601. Oxford University Press, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/190526424.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2021.

- Unni, V. K. “Indian Patent Law, and TRIPS: Redrawing the Flexibility Framework in the Context of Public Policy and Health.” Pacific McGeorge Global Business. & Development Law Journal, 2012, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 323-342. Scholarly Commons, https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/globe/vol25/iss1/12. Accessed 27 March 2021.

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications