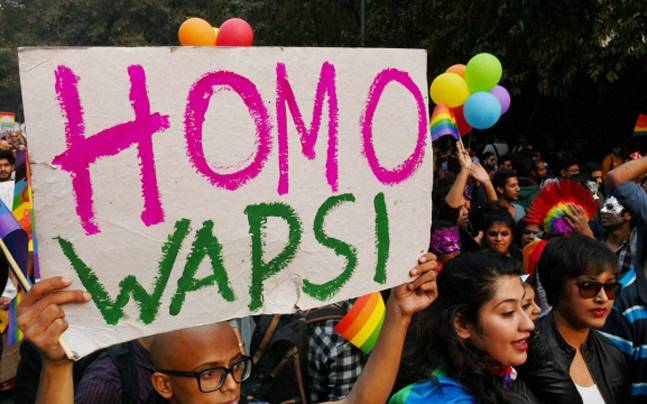

In this article, Prathiksha Ravi, a law graduate from Institute of Law, Nirma University, talks about the impact of the landmark ‘Right to Privacy judgement on the laws of homosexuality in India.

Introduction

“If the right to privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion.” – William J. Brennan[1]

Privacy is the ability to seclude oneself and their information by expressing to others in a selective manner. The concept of privacy differs from country to country but share a common theme. Most countries protect against the invasion of privacy by Governments, corporations or other individuals.

In India, the right to privacy as a fundamental right has been debated numerous times culminating into a landmark judgement which granted the right to privacy as a right protected by the Constitution as a ‘fundamental right’.

In light of this recent judgement, there stems a ray of hope for those fighting to legalize homosexuality in India by declaring Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code as ‘unconstitutional’. What happens between two individuals of the same sex inside their own private sphere must be protected from invasion by the government and its officials. The right to privacy judgement is one step towards attaining the above goal.

The Privacy Judgement – Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India

Facts of the case

A three-judge bench of the Supreme Court brought forth the following debate of whether the Aadhar Card scheme of the government violates the right to privacy. Two major prior cases were observed – M.P Sharma v. Satish Chandra and Kharak Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh. These cases contained that the Indian Constitution does not specifically protect the right to privacy. Further judgements like Gobind v. State of Madhya Pradesh and others which held that right to privacy is enshrined as a fundamental right in the Constitution could not be held as ‘good law’ due to it being decided by smaller benches. Thus, the debate on the ground of not being able to reach a conclusion was sent to a nine-judge Constitutional bench headed by the then Chief Justice of India, Justice J.S. Khehar.

Issues

The nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court deliberated on the following issues –

- Whether privacy is a constitutionally protected value?

- Whether the right to privacy has the character of an independent fundamental right or does it come under the purview of right to life and personal liberty?

- What are the doctrinal foundations to the right to privacy?

- What is encompassed within the purview of Privacy?

- What is the nature of the regulatory power of the State?

The jurisprudence of the below two cases was examined

M.P Sharma v. Satish Chandra

The challenge, in this case, was that searches conducted by the government were violative of fundamental rights of the petitioners namely Article 19(1)(f) and Article 20(3) of the Constitution of India. The Court took into its motion only the contention of the violation of Article 20(3) and held that guarantee against self-incrimination is not offended by a search and seizure.

Kharak Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh

The court, in this case, held that freedom governed under Article 19(1)(d) of the Constitution is not infringed by a watch being kept over the movements of the suspect. They pointed out that:

“The right of privacy is not a guaranteed right under our Constitution and therefore the attempt to ascertain the movements of an individual which is merely a manner in which privacy is invaded is not an infringement of a fundamental right guaranteed by Part III.” [2]

Dissenting judge, Justice Subbarao held that, even if the right to privacy is not considered as a fundamental right within Part III of the Constitution, it is an essential ingredient of personal liberty.

Judgement

The nine-judge bench concluded that Right to Privacy is a fundamental right enshrined in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. It over-ruled the before cases of M.P Sharma v. Satish Chandra and Kharak Singh v State of Uttar Pradesh.

The following points were highlighted in the judgement:

- In the case of M.P Sharma v. Satish Chandra, the judgement states that right to privacy is not an independent right under the fundamental rights given in the Constitution but the judgement also does not specify whether it can be treated as a right under Article 19 or Article 21, thus overruling the judgement to that extent.

- In Kharak Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh, the second part of the judgement which states that ‘right to privacy’ is not guaranteed under the fundamental rights is overruled.

- Privacy is a constitutionally protected right under Article 21 which talks about the right to life and personal liberty.

- The right to privacy includes in its core the preservation of personal intimacies such as

-

- Sanctity of family life

- Marriage

- Procreation

- Home

- Sexual Orientation

- The Right to privacy is the right to be left alone.

- The invasion of privacy must be justified on the basis of a law which is fair, just and reasonable.

- The fundamental right to privacy has its limitations which will be identified on a case to case basis.[3]

-

Laws regarding Homosexuality in India

Homosexuality is considered as a taboo in Indian Society which results in the isolation and subjugation of those who have different preferences when it comes to choosing a partner for life. The criminalization of homosexuality in India is due to Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860.

Section 377 states that:

“Unnatural offences — Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal, shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine.”

Section 377 is a product of a law made during the British era which criminalizes same-sex conduct even of consenting adults.

Naz Foundation v. Government of NCT Delhi and Others.

Naz Foundation, an NGO which works for HIV/AIDS sufferers brought a claim in public interest stating that Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 was unconstitutional as it violated fundamental rights such as Article 14,15,19 and 21. The petition stated that Section 377 was being used to criminalize consensual sex between two consenting adults in the name of it being ‘unnatural’. The government of NCT claimed that the law should be kept valid as ‘homosexuality does not follow societal values’.

The Judgement clearly stated that Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code was unconstitutional only when it violated Articles 14,15 and 21.

This judgement was challenged by various parties. The judgement was overturned by the Supreme Court of India in the following case.

Suresh Kumar Kaushal v. Naz Foundation

The landmark judgement given by the Delhi High Court in the Naz Foundation case was questioned as to whether Section 377 actually violates Article 14,15 and 21 of the Indian Constitution. The Supreme Court held that:

“Section 377 does not criminalize a particular people or identity or orientation. It merely identifies certain acts which if committed would constitute an offence. Such a prohibition regulates sexual conduct regardless of gender identity and orientation”.[4]

As of the today, Homosexuality is criminalized under Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860.

Impact of the Privacy judgement on Homosexuality in India

“If Privacy is to be construed as a protected constitutional value it would redefine in significant ways our concept of liberty and entitlements that flow out of its protection” [5]

One of the points mentioned by Naz Foundation was that Section 377 of Indian Penal Code, 1860 was that it violated the right to privacy and right to dignity under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The concept of the right to privacy due to the prevalence of M.P Sharma v. Satish Chandra and Kharak Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh was not a ‘fundamental right’ enshrined under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. This changed after the judgement in the case of Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India, where the Right to Privacy is now considered as a fundamental right overruling the previous cases.

Three out of the five judgements in the case declaring privacy as a fundamental right also talked about its impact on Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860.

The following excerpts highlight the same

Sexual orientation, an essential attribute of Privacy should be protected as a fundamental right under Article 14,15 and 21.

Justice Chandrachud held that – “Sexual orientation is an essential attribute of privacy. Discrimination against an individual on the basis of sexual orientation is deeply offensive to the dignity and self-worth of the individual. Equality demands that the sexual orientation of each individual in society must be protected on an even platform. The right to privacy and the protection of sexual orientation lies at the core of the fundamental rights guaranteed by Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution”[6]

Right to Privacy is applicable to the LGBTQ community and the Supreme Court erred in saying that the law cannot be changed in favour of a minuscule portion of the society.

As per Justice Sanjay Kaul, while agreeing with Justice Chandrachud held that

“right of privacy cannot be denied, even if there is a minuscule fraction of the population which is affected.”[7]

Will the Courts now re-examine Section 377 in light of this judgement?

In light of this landmark judgement, there lies a ray of hope for those fighting against decriminalisation of Section 377. The Supreme Court in the ‘Right to Privacy’ judgement held that the case of Suresh Kumar Kaushal v. Naz Foundation, which held that right to privacy does not fall under the purview of a fundamental right enshrined in our Constitution now stood invalidated.

Arguments for the decriminalisation of Section 377:

- Section 377 criminalises activities which take place between two consenting adults within the privacy of their home. Right to Privacy is now an integral part of Article 21 of the Constitution which ensures right to life and liberty

- Section 377, though made to widen the definition of ‘rape’ as an offence to include acts that do not fall under the purview of the rape definition, in present-day acts as a pass to allow persecution of the LGBTQ Community which is a violation of fundamental rights which guarantees non-discrimination based on sexual orientation.

- The Delhi High Court in its judgement decriminalising Section 377 held that:

“The concept of privacy allows the formation of relationships without the fear of outside intrusion. This comes under right to dignity and right to privacy under Article 21 of the Constitution.” [8]

- The argument in Suresh Kumar Kaushal v. Naz foundation was that only minuscule portion of the population of India come under the LGBTQ community, thereby there was no reason to change the law made by the legislature. This was dismissed by Justice Sanjay Kaul in the ‘Right to Privacy’ case and he stated that the right to privacy cannot be denied even if it affects only a minute fraction of people in the country.

Conclusion

The Right to privacy is the right to protect oneself from government intrusion. It has been declared as an integral part of the fundamental rights of our country mainly under Article 21 of the Constitution which talks about “life and personal liberty” by the recent landmark judgement of Justice K.S Puttaswamy v. Union of India.

This judgement has now paved the path to decriminalize Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 which prohibits homosexual relations amongst other things. The Naz Foundation judgement by the Delhi High Court was overturned by the Supreme Court by stating the point that ‘right to privacy’ is not a fundamental right. The case can be brought forth again thanks to the present ruling by a nine-judge bench that ‘Right to Privacy’ as a part of the fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution.

References

[1] William Joseph Brennan, Jr. was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1956 to 1990

[2]Justice Kaul in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India [Writ Petition (Civil) no 494 OF 2012]

[3]p.351, Kharak Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh 1963 AIR 1295

[4] Suresh Kumar Koushal & Anr vs Naz Foundation & Ors on 11 December 2013

[5] Justice D.Y Chandrachud in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India [Writ Petition (Civil) no 494 OF 2012]

[6] The Indian Express, ‘Right to privacy case is a fundamental right: Two judgments that Supreme Court overruled’ http://indianexpress.com/article/india/right-to-privacy-judgment-a-fundamental-right-here-are-the-two-judgments-supreme-court-overruled-4811117/ [Date of Visit: 04/02/2017 Time of Visit: 11:30 am]

[7] Justice Kaul in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India [Writ Petition (Civil) no 494 OF 2012]

[8] The Wire, ‘Right to Privacy a Fundamental Right, Says Supreme Court in Unanimous Verdict’,

https://thewire.in/170303/supreme-court-aadhaar-right-to-privacy/ [Date of Visit: 07/02/2018 Time of Visit: 10:45 am]

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications