This article has been written by Priyanka Saraswat, pursuing the Diploma in Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Laws from LawSikho.

Table of Contents

Introduction

What do Darjeeling tea and champagne have in common? Probably nothing other than being named after the places they originate from. They enjoy a global monopoly thanks to this reference to their birth regions. The names suggest and convey to the consumer information about its taste, aroma, quality, and the overall experience one is about to obtain from it. That’s all in a day’s work for a geographical indication (GI) tag. Products such as Scotch whisky, Swiss watches, and Parmesan Reggiano cheese can legally create in the minds of the consumer the idea that there is no other place that can provide them with the authenticity and quality that their place of origin can, thanks to this tag.

A G.I. tag is an indicator that identifies the originating point or manufacturing location of agricultural, natural, or manufactured goods where the quality, reputation, or any other important characteristic can be essentially attributed to its geographical origins. From the time the Act came into force in 2003, there have been a total of 370 GIs registered in India, which is relatively a very small number compared to the Trademarks that get registered every year. This article attempts to simplify the registration process for you and asks whether registration is even beneficial to producers in the first place, focusing on some of the successful and not-so-successful tags granted.

Geographical indication : a brief overview

When the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) was signed in 1994, safeguarding products and goods based on their regional specifications became another obligation of the member states. Based on this, India passed its sui generis act called the Geographical Indication of Goods Act in 1999. The need for specific legislation also arose due to the Basmati RiceTec controversy in the 1990s, especially because unless the product is protected by G.I. in the country of origin, other countries are not obligated to reciprocally protect the claim under the TRIPS Agreement.

According to the Act, any agricultural, natural, or manufactured product originating from a definite geographical territory that can be attributed to its production or processing can obtain a G.I. tag for that region, and resultantly any such goods from that region can utilize the tag. The Geographical Indication Rights prevent third parties and unauthorized users from using the tag in products that do not conform to the applicable standards.

If a trademark tells you who made a certain product, a geographical indication helps identify the region it originates from. The region imbues to the product a certain specific value emerging from the cultural as well as ecological advantages that can be economically exploited. However, as opposed to other intellectual property rights, a GI is not the property of an individual or a company but a public property that allows every registered user, be it a producer or a manufacturer, in that specific region to use the GI tag as long as the quality of the product can be accredited to the said region.

The requirement for GI legislation is twofold: first, it is meant to safeguard heritage crafts and historically grown natural products of the country from counterfeit products that harm their reputation; second, the internationally recognized standing of a product can help in the increase of exports and give the country an economic boost.

Benefits of obtaining the tag

Every region has something unique and exclusive to offer and the G.I. tag honours and recognises these distinctive identity markers of these products and methods of production. There are plenty good reasons to opt for one such as maximization of the export value and safeguarding cultural heritage, amongst others:

- Branding: The regional specificity becomes a brand in itself acting as a marketing tactic. It also helps in the elimination of intermediaries leading to higher profits for the producers of the heritage art and goods.

- Proof of quality: A GI tag is a guarantee of premium quality of the product coming from its association to a certain region and the history of that product in that territory, especially as it is recognized by the national government of the country of origin (and in some cases, multiple governments all over the world). This in turn increases the possible income in the market both from the premium quality and the heritage attached to it.

- Authenticity: A similar superior quality can be imitated by the means of the power loom and other industrial methods, which acts as a threat to the uniqueness of the handcrafted material but the presence of a GI tag preserves the essence derived from centuries of practice and honing the craft by giving the product a market edge over the imitations.

- Cultural protection: The products that receive a GI tag are rooted in the heritage of the place whether they are natural or manufactured goods, and the tag helps preserve the traditional methods of production helping protect the local culture and heritage. Many crafts that had been dying from the lack of patronage have been revived post being awarded the tag from the awareness and publicity created resultantly.

- Increase in tourism: There’s a direct connection between the global reputation gained from the protection of the GI tag and the increase in tourism based on the global demand for these products.

- Economic boost: The economic value of a product with a GI tag attached is higher than a regular product due to the promise of quality attached to it and it also helps boost the demand of the product in the market.

Process of registration : is it difficult?

Registration of geographical indications is not mandatory just like other intellectual property rights such as copyright and trademark; it only affords the producers and proprietors better legal protection in case of infringement.

Any association of persons, producers, organisations, or authority established by or under the law can file for registration as a registered proprietor. Whereas any producer of the said goods can apply to become an authorized user of the GI tag by applying in writing and paying a prescribed fee. It is a fairly easy process. Generally, the application can be filed either by a legal practitioner or a registered agent.

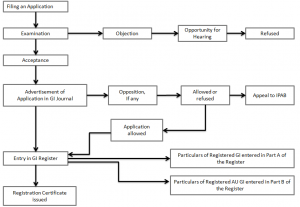

Image courtesy: IP India website

Image courtesy: IP India website

-

Step 1 : the application

The first and foremost thing is to check whether the product falls under the prescribed definition as per Section 2(1)(e) of the Act. Additionally, also cross-check that GI does not fall under the prohibited category as per Section 9 of the Act. (Please note that the prohibited category refers to the tag or the indicator to be registered for identification of the goods and not the goods themselves). Once that has been confirmed, an application can be filed as per Section 11 of the Act which prescribes that the application, made in triplicate, should contain:

- A statement of the case is made,

- Class of goods (as per the Fourth Schedule of the G.I. Rules),

- Geographical map of the territory (three certified copies),

- Description of the appearance of the G.I. – whether a wordmark, or figurative element, or both,

- Details of the applicant.

The application should be sent to the G.I. Registry in Chennai, signed either by the applicant or by the agent filing it.

-

Step 2 : scrutiny and examination

The Registrar will examine the application for any deficiencies or irregularities that, if any, need to be corrected within a month of being communicated to the applicant. A consultative panel of subject matter experts will assess the claims made and ascertain the correctness of the same based on which an examination report is issued.

-

Step 3 : objections or acceptance

If the Registrar has any objections concerning the application, the said objections will be communicated and the applicant will have to show cause or apply for a hearing within two months of receiving the notice. The Registrar will make a final decision on the same, upon which, if required the applicant can request an appeal within a month. If the application is accepted, within three months of the communication of such acceptance, the same shall be published in the Geographical Indications Journal.

-

Step 4 : opposition

Anyone opposed to the application can file a notice of opposition within three months of the application being published in the journal. A copy of any such notice will be communicated to the applicant who shall file their counter statement within two months. In case the applicant does not file a counter-statement, the application will be deemed abandoned. The evidence can be led thereafter and the date of hearing fixed.

-

Step 5 : registration

Depending on the result of the hearing on the opposite, the application shall be allowed or refused. In case of refusal, the applicant has the option of appeal to the appellate authority, which for GI is the High Court after the abolition of IPAB.

If the application is allowed, registration will be granted to the GI and the particulars shall be entered into Part A of the Register. A registration certificate will be issued to the applicant and the registration shall last for a term of 10 years from the date of filing of the application after which a renewal application needs to be made along with the payment of a renewal fee.

-

Step 6 : authorised users

Any person claiming to be a manufacturer or producer of the protected goods needs to file to be registered as an Authorized User under Section 17 of the Act, which is mandatory for the purpose of utilizing the GI tag granted. The process of application is the same as that for the application for the tag. Once granted, the particulars of the Authorized User are entered into Part B of the Register. The authorization is granted for a period of 10 years or till the date of the expiration of the GI tag, whichever is earlier.

Restrictions

- A single person cannot apply for the GI registration; the application can only be filed by an association of producers, an organization or authority established by or under the law. A person can nonetheless apply to be a registered or authorised user of a registered tag.

- The right provided under this act is only a positive right and therefore the owner of a GI tag cannot prevent someone from making a product by incorporating the same techniques or procedures as set out in the standards for that specific indication.

- A GI tag being a public property, cannot be assigned, licensed, or otherwise transmitted like other private intellectual properties can be. However, the right of an authorized user can devolve onto an heir by succession in the title. The financial advantage of the GI tag, therefore, is only the economic boost it provides to the producer community.

- A product grown or manufactured in a region afforded GI protection can still be considered infringing goods if not produced by an authorized user or according to the standards set out in the code of practice for that specific geographical indication.

Success stories and those of failure

When fruitfully managed the GI tags can become global success stories such as the world-renowned Darjeeling tea, but there have also been instances where even the GI tag could not save the community that depended upon the protected craft.

Chanderi Sarees, Madhya Pradesh

An estimated 60 percent of this small town in Madhya Pradesh are dependent on the handloom weaving industry for creating these sarees. The craft, which was given royal patronage once upon a time, began facing a decline in demand due to the high competition from the power-loom products and the difficulty in distinguishing genuine Chanderi craft and non-Chanderi products. The consequential loss of jobs led to the younger generation migrating out to look for work. The application for registration as a GI was made by the Chanderi Development Foundation in 2005. Which after large-scale steps taken to utilize the tag post-registration including marketing, creation of e-commerce portal, conducting sensitization workshop, free distribution of the GI logo, led to bulk orders such as stoles for athletes and merchandising during the Commonwealth Games and tie-up with brands such as FabIndia.

Venkatagiri Sarees, Andhra Pradesh

A similar product hailing from the Nellore District of Andhra Pradesh is the lightweight fine cotton Venkatagiri saree, with close to 3 centuries of history to boost for. The region and its craft faced the same difficulties and competition as their Madhya Pradesh counterpart before opting to register for a GI tag. However, the post-registration story is poles apart. The products were promoted by the Andhra Pradesh State Handloom Weavers Cooperative Society and close to 400 new designs were introduced but the lack of proper publicity and marketing for the authentic distinctive craft and the blatant copying of the designs by textile companies has led to no advantage coming to the traditional weavers. The actions to be taken post attaining the tag such as strict monitoring and quality control, marketing strategies, publicity, have not been paid attention to leading to a decline in the craft.

Both these products received the tag however one was successful in economically exploiting the advantage while the other dwindled from the lack of care and attention. The fact of the matter is that obtaining the GI tag is only half the battle, utilizing it to safeguard your products against infringements and counterfeits is another uphill climb.

Why is the GI tag not as popular in India?

- A majority of the producers and manufacturers of traditional crafts, agricultural goods, and natural products come from marginalised socio-economic classes and rural regions that do not have access to legal support and knowledge. Organising themselves in associations to apply for geographical indications is a difficult and tedious task. Additionally, the lack of information regarding the application process, or even knowledge of its existence in the first place is another reason why many communities do not opt for it.

- In a country that relies on oral history more than documentation, the strict documentary proof of origin required for the purpose of registration is a formidable hurdle. This has been the case for the traditional rice wine of Assam, ‘Judima’ made by the Dimasa tribe, for which gathering documentary proof has become a major roadblock.

- Instead of focusing on products that need protection for the high volume of export and their standing in the global market or the heritage crafts and products, India has awarded the G.I. tag to certain goods that have nothing much to gain commercially from the tag such as the Tirupati Balaji laddoos.

- Additionally, there might be products that are not legally allowed to be transported such as Goan Feni, which defeats the export advantages of the tag. A simultaneous amendment and revamp of laws around the protected products becomes a requirement but is often not paid attention to.

- While the prescribed fees for the application under the G.I. Act, 1999 is Rs. 5,000 and the additional paperwork can cost a couple of thousands more, there are certain additional hidden costs attached to the process for the purpose of continued protection. In the case of Pashmina, it cost the Jammu & Kashmir government a massive sum of 44 crores to set up the Pashmina Testing and Quality Certification Centre for protecting their intellectual property. Footing such hefty bills is not possible for many small communities of artisans and craftsmen.

- While the GI tag helps boost exports and increase the income from the sale of such exotic items in foreign markets, not all producers are involved in direct exports of the product. Additionally, the products awarded the tag, especially in the case of handicrafts, are based on meticulous handiworks the process of which are safeguarded in the GI. However, the machine-made alternatives of such products that flood the market are cheaper and therefore preferred by consumers that give greater importance to price than to authenticity.

- Obtaining the tag is not enough. Under the Act, all producers wishing to utilize the tag need to register themselves as authorized users, which is another complete and long process in itself. In the case of Kanchipuram Silk sarees, the regional manufacturers applied for registration as authorised users only after four years of the tag being awarded.

The Tripartite bid for registration of Basmati

India has filed applications for the recognition and protection of Certification Mark in 19 foreign jurisdictions while it has been registered in four countries, namely, UK, Kenya, New Zealand, and South Africa. Basmati is long-grain aromatic rice produced particularly in the Indo-Gangetic plains for which GI has been granted in India to 7 states (Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Delhi, Uttarakhand, Jammu & Kashmir and Uttar Pradesh) in 2015 after an order by the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB).

India’s application for exclusive GI tag in EU’s Council on Quality Schemes for Agricultural and Foodstuff has been opposed by Pakistan in December 2020, though India states that with our joint heritage and common history over rice, Pakistan is also entitled to secure its trade and export. Earlier this year, Nepal also threw its hat in the ring by opposing India’s application. While Pakistan’s bid has some standing with their domestic GI tag for Pakistani Basmati, Nepal doesn’t have a GI regime in place and still protects them under their trademark laws (though GI status is not a prerequisite for filing opposition). Additionally, some reports claim that Nepal imports almost all its Basmati rice from India.

The process will take another few months as under the framework the parties will now be engaging in consultation with the Council trying to reach an agreement. If no agreement is reached, the Council will then hear the matter accordingly and decide.

Conclusion

GI is one of its kinds of protection afforded to producers and manufacturers of historical crafts and goods but it’s not without its follies. The legislation and statutes in place are far from perfect even after being in place for almost two decades. This is why both its reputation and usefulness are minuscule at best.

This, however, does not mean that opting for a GI tag is a wasteful act. The law cannot be done away with because it will leave vulnerable communities with a void that cannot be filled with any of the existing laws. A legal safeguard, however lacking, is always an advantage to have in your corner, and with the popularity of it slowly on a rise, there are greater possibilities of the law changing into a better and more beneficial one. The GI tagged products require the support of government mechanisms for protection and publicity once the tag has been granted with, an increase in government-aided sale systems in major markets, easier ways to prove authenticity, and means for better marketing, being some of the suggested steps.

References

- https://ipindia.gov.in/faq-gi.htm

- https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/locked-out-without-a-gi-tag/article20944930.ece

- https://www.managingip.com/article/b1kblzz0v6csrq/is-geographical-indications-sufficient-to-aid-to-the-indian-economy

- https://www.altacit.com/resources/gi/the-advantages-of-geographical-indicators/

- https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/dindigul-locks-to-kandangi-saris-would-gi-tags-revive-an-industry/article29311542.ece

Students of LawSikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals, and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications