This article has been written by Aksshay Sharma, Department of Laws, Panjab University. This article explains the meaning of Notice under The Transfer of Property act, with relevant illustrations. This article also makes an effort to simplify the language of the provision as given in the bare act.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The concept of Notice for the purpose of The Transfer of Property is given under Section 3 of Transfer of Property Act, 1882 (TPA). Notice means to have knowledge of something i.e. to know something. In law, it means knowledge of a fact. It is used to decide on conflicting claims of two parties. In law, the Notice or Knowledge of a fact affects one’s legal rights and liabilities.

Under Section 3 of TPA Notice can be; “Actual or express Notice” or “Constructive Notice”, or it may be imputed to the transferee when information of the fact has been obtained by his Agent.

Express or Actual Notice

Actual notice means when a person actually knows about the existence of a fact. The fact must be definite information given in the course of negotiations by a person interested in the property. The information of fact should not be a rumour or hearsay and thus is not bound by such information.

In other words, actual notice takes place when the information is such that it would operate upon the mind of a rational man and would make him act based on the knowledge so acquired.

Constructive Notice

According to Section 3, a person is said to have notice of a fact, which he would have known, but for his “gross negligence” or “willful abstention from making an enquiry or search” does not know. However, it is such knowledge which a person with ordinary prudence ought to have known. In other words, constructive notice of facts are those facts which a person ought to have known, but because of gross negligence or wilful abstention does not know it.

Thus in Constructive notice, there is a legal presumption, that a person should have known a fact as if he actually knows it.

Therefore Constructive notice is knowledge of those facts which a court imputes on a person. If the circumstances indicate that a reasonably prudent person ought to have known a particular fact related to the transaction of transfer, then he will be deemed to know it.

Illustration: A sells the house by a registered document to B. He later enters into a contract with C to sell him the same house. Law imposes a duty upon C to inspect the registers at the Registrar’s office, and if he does that, he would come to know about the sale in favour of B. A failure to inspect the register will be detrimental to the interests of C, as he would be imputed with constructive notice of the registered transaction.

Wilful abstention from enquiry or search

Wilful abstention can be understood from observations in Jones v. Smith (1841)

“cases in which the court is satisfied from the evidence before it that the party charged has designedly abstained from the inquiry for the purpose of avoiding it”.

For wilful abstention, there has to be some starting point, some hint or suspicion which would require some investigation to reveal the truth about a transaction. If in such cases the transferee fails to investigate, with a fraudulent intention to not know the real truth, then the court will assume that the transferee had some idea of that fact.

For instance, if a property is mortgaged to a bank by deposit the title deeds and the mortgagor later sells the property to a lady without disclosing the fact of the mortgage, and she does not insist on inspecting the title deed, then it will be presumed that the buyer willfully abstained from inquiring and will be imputed with constructive notice of the mortgage.

Gross Negligence

Constructive notice also applies where the transferee ought to have known some fact, but because of gross negligence, he is unaware of it. Gross Negligence was explained in Hudston v. Viney as gross negligence “does not mean mere carelessness”. It means carelessness of such an “aggravated nature”, that indicates an attitude of “mental indifference to obvious risks”.

For instance, If the transferee fails to read a note on the paper that the property is subject to a charge, while the papers are in his possessions, then the court will not entertain the plea of no Notice and will impute knowledge or notice of charge.

Thus Constructive notice demands due diligence with respect to transactions related to the transfer by the transferee.

Illustration: A sold his property to B for 10lakhs and delivered possession of it to B. B pays 5 lakh immediately, at the time of conclusion of the contract and promises to pay the balance 5 lakh after 6 months.

The fact that the balance of 5 lakh has to be paid by B to A is written in the title deed. B eventually fails to pay A the remaining amount and mortgages this property by depositing the title deed to C and gets a loan of 5 lakh from C on the basis of the title deed.

B fails to pay C also and this property which was mortgaged to C is sold by C.

Now A files a suit against C to recover his 5 lakh. The question whether C is liable or not will be decided by imputing Constructive Notice to C. It must be noted that it was already written in the title deed that B has to pay A the balance amount and these title deeds were in possession of C and on the basis of these title deeds the loan was advanced to B. Thus it can be said that C “would have known” about the nature of the title deed.

Moreover, C as a reasonably prudent person ought to have examined the title deed carefully to get notice of the fact that B is supposed to pay A 5 lakh.

If he fails to do that he has committed “gross negligence” under Section 3 of TPA. Further, if he had examined the deeds and discovered the fact of payment to A, then he ought to have investigated further. If he does not do it then he is guilty of “willful abstention from making an enquiry or search” under section 3 of TPA.

Thus, whether the transferee is to be imputed with constructive notice or not has to be determined by the circumstances, surrounding a transaction. Thus it is a question of fact and not of law.

Similarly, where the bank returns the title deeds, which are the only security it has against the loan advanced by it, and the owner mortgages the same title deeds with another bank to secure an overdraft, the first bank is guilty of gross negligence in parting with the title deeds. (In Lloyd’s Bank v. PF Guzdar & Co)

Registration of Document as Constructive Notice

According to Explanation 1 to Section 3, if a transaction relating to the immovable property needs to be effected by a registered instrument, under law, then the registration of the document will be deemed as Constructive Notice. The notice of such instrument will be deemed from the date of registration of such instrument.

It must be noted that registration amounts to notice only when it is required by law. If registration is not compulsory under law, then the fact of registration does not amount to notice under TPA.

A sells the house by a registered document to B. He later enters into a contract with C to sell him the same house. Law imposes a duty upon C to inspect the registers at the Registrar’s office, and if he does that, he would come to know about the sale in favour of B. A failure to inspect the register will be detrimental to the interests of C, as he would be imputed with constructive notice of the registered transaction. All purchasers are thus under a legal obligation to exercise diligence in examining the title recorded in the register to avoid uncertainties and the risk of any sort.

Further Explanation 1 to Section 3 states that Constructive notice of registration will take place only if 3 conditions are satisfied:

- That the document was registered in accordance with the Registration Act, 1908.

- That the instrument or memorandum has been duly entered in the book or registers kept under Section 51 of the Registration Act, 1908.

- And that the particulars of the transaction have been correctly entered in the index under Section 55 of the Registration Act.

Actual Possession as Notice

According to Explanation 2 of Section 3, a person acquiring an immovable property shall be deemed to have notice of the title of any other person, who for the time being actually possesses the property.

It means that when a person, other than the transferor/owner, is in actual possession of the property, then it is necessary for a prospective buyer of that property, to ascertain all the rights, which the person in actual possession really has related to the property.

Thus it is the duty of the subsequent purchaser to inquire, about the precise character of possession, from the person, who for the time being actually possesses the property.

For instance, A lets out his property to B by a registered lease deed for 10 years. Before the expiry of the said period, A enters into another contract with C, by which he agrees to sell it to C for a consideration. Now C must inquire from the tenant (B), about the nature of possession by B, because C nevertheless will be bound by the constructive notice of B’s title.

However, for constructive notice of possession, the possession must be actual possession and not constructive possession. For instance, A contracts to sell land to B, and B puts another person in possession of the land. A further sells land to C. In this case C is not affected by the notice of B’s interest.

Notice of Agent

The general principle of the law of agency is that an agent stands in the place of the principle thus notice of fact by the agent will be deemed to be noticed by principle as well. This is based on the legal maxim qui facit per alium facit per se i.e. He who does by another does by himself.

The notice of a fact will be imposed on the principal irrespective of whether his agent did actually communicate the fact to the plaintiff or not. The principle behind this is that no person would be allowed to get rid of the doctrine of notice by simply employing an agent. This is to protect the innocent party. In Gokul das v. Eastern Mortgage & Co. it was held that knowledge or information obtained by a solicitor or, in any case, will bind him as well.

However, the agent’s knowledge will not operate as knowledge of the principal, where the agent fraudulently conceals the fact from the principal. But mere concealment of fact will not amount to this aspect as a defence. For this to act as a defence, the party imputing Constructive notice to the principal must act in collusion with the agent or is aware of agents’ fraud.

Conclusion

Thus it can be said that Constructive notice is a manifestation of the rule of Caveat Emptor. This is because according to Constructive notice, a person ought to have known a fact as if he actually does know it. It presupposed that in property translation a transferee ought to ascertain and verify certain facts for safeguarding his own interest. Thus he must be aware of the nature of the transaction. These facts may relate to property or the transferor, like whether the property is free of any charge or encumbrances or whether the transferor is competent to transfer the property or not.

If the property is encumbered, then the exact nature of the encumbrance ought to be ascertained by the transferee. Law puts it as the duty of the transferee, as a reasonably prudent person to be reasonably vigilant and diligent to ascertain the facts, inspect the documents relating to property in possession of the transferor, inspecting concerned persons, even with relevant statutory authorities, if required. Failure to do this would result in the imposition of Constructive notice.

References

- Transfer of property act by S.N. Shukla

- Property law, Poonam Pradhan Saxena

- Mulla, The Transfer of Property Act, 13th edition, Dr Poonam Pradhan Saxena

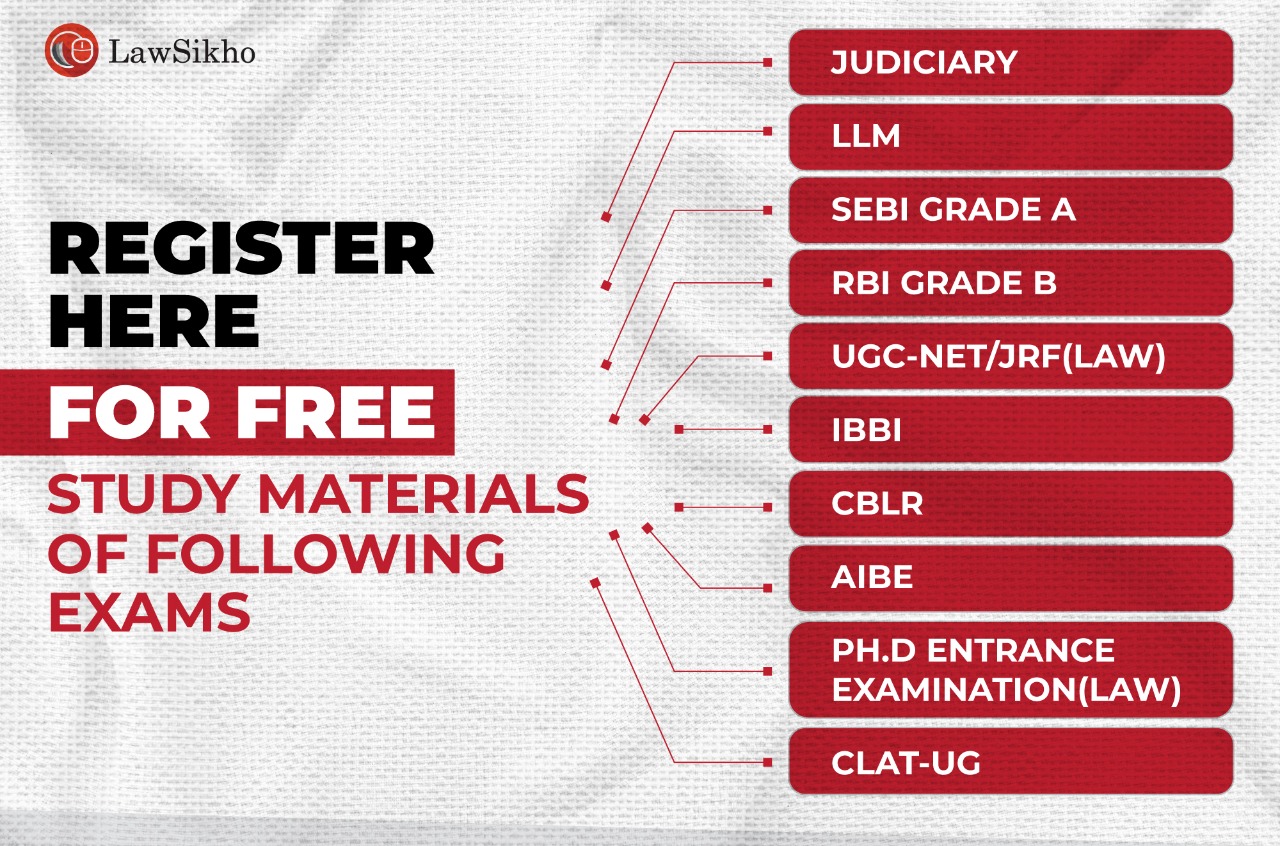

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals, and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications