This article has been written by Akanksha Singh. This article is an exhaustive piece of work on the detailed study and analysis of the landmark case of ‘The Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Cooperative Societies and Others (2022)’. The article provides a comprehensive learning experience for the readers as it also includes a thorough explanation of the provisions of ‘Entitlement to Pension’, along with other relevant case laws under the Service Law in the Indian jurisprudence.

Table of Contents

Introduction

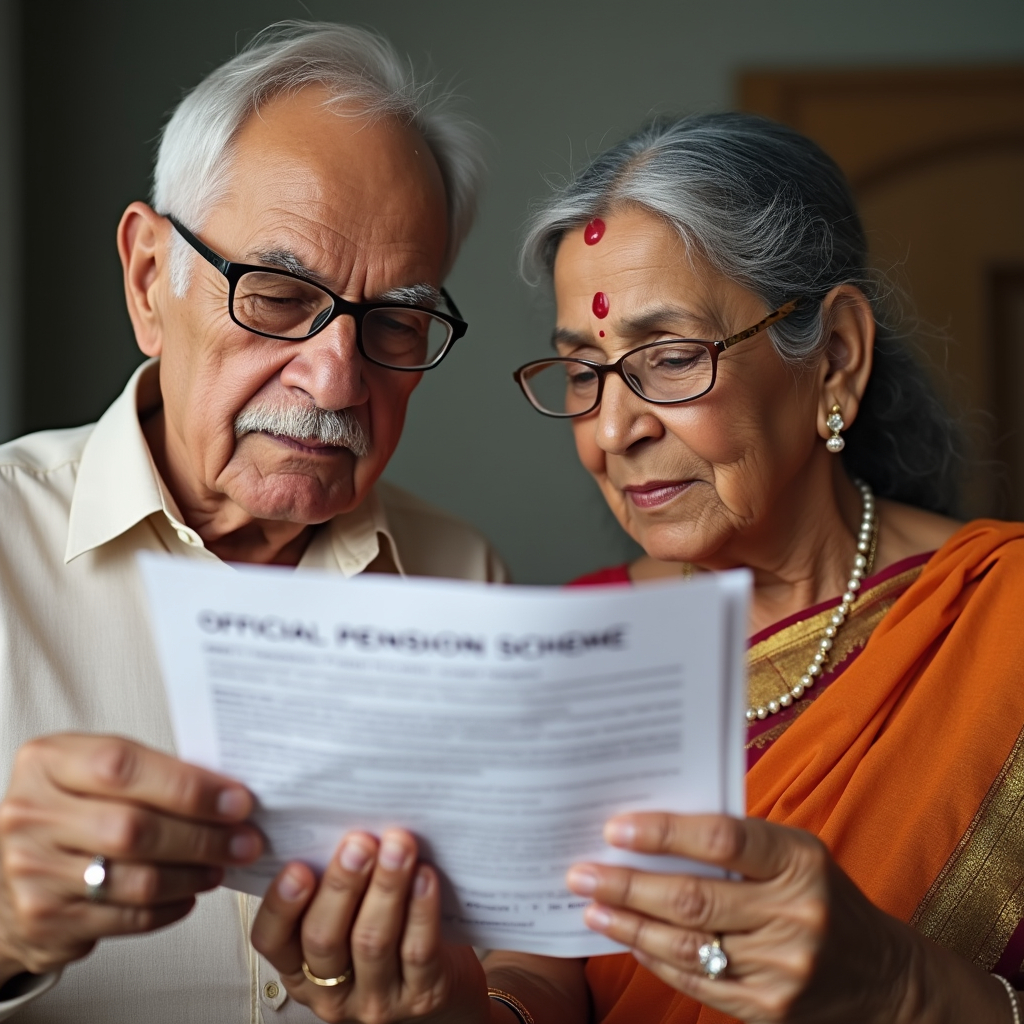

The case of ‘The Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Cooperative Societies and Others (2022)’ is the latest and landmark case of pension to employees in service law. Service law covers a wide variety of topics, such as hiring, promotion, disciplinary measures, termination and pension, when it comes to cooperative societies and cooperative banks. The case of ‘The Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Cooperative Societies and Others (2022)’ put forth significant questions before the High Court of Punjab and Haryana at Chandigarh, and the Apex Court of the country, the Supreme Court of India regarding the ‘Entitlement of Pension Scheme’ of the retired employees and the serving employees. The case brought to light the need for a balance between the legal rights of the employees and the right of the organisation to amend rules. This case set a precedent in light of providing a safeguard put in place to shield the serving and retired employees from unfair or unreasonable conditions of employment with respect to the entitlement of pensions to employees. With its ruling, the Supreme Court of India sought to set a guideline in terms of how an organisation such as a cooperative bank can amend its rules regarding the terms and conditions and the benefits of such employment, while strict adherence to the general principles of fairness, reasonable and natural justice. The historic ruling of the Supreme Court of India highlights the intricate relationship that exists between rules governing cooperative banks and the rights of their employees.

This case also raised questions that intersected both service law and constitutional law of the country. The court examined whether certain decisions of ‘The Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd.’ were violative of Article 14 and Article 16 of the Constitution of India. It dwells upon the concept of ‘legitimate expectation’ in the service law. It also talks about the vested or accrued rights of the employees with respect to the rights provided in any particular service as per the terms and conditions of the service. The application and interpretation of the concepts of service law with respect to pension schemes in the setup of a cooperative entity can be better understood by examining the particulars of this case in great depth.

Details of the case

- Name of the Case: The Punjab State Coop. Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Coop. Societies and others

- Case Number: 297-298 of 2022

- Equivalent Citations: (2022) 4 SCC 363

- Acts involved: The Employee’s Provident Funds and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1952

- Name of the Court: Supreme Court of India

- Bench: Justice Ajay Rastogi and Justice Abhay S. Oka.

- Name of Petitioner/Appellant: The Punjab State Coop. Agricultural Development Bank Ltd.

- Name of the Respondent: The Registrar Coop. Societies

- Subject-Matter of Case: Withdrawal of Pension Scheme

- Date of the Judgement: January 11, 2022

Facts of the case

In this case, multiple appeals were filed on the same issue of dispute. In this batch of appeals, the appellant is the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd, while the original writ petition was filed by the retired employees of the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd.

29th July 2019: Special Leave Petition filed

At the same time, the serving employees of the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. have preferred a special leave petition against the self-same common judgement dated 29th July 2019 and 4th October 2019 passed by the Division Bench of the High Court of Punjab and Haryana at Chandigarh. The Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. is a registered cooperative society. Under the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd., the service conditions of the employees are governed by the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Land Mortgage Banks Service (Common Cadre) Rules, 1978.

The aggrieved retired employees became members of the Bank Pension Scheme, which was introduced with effect from 1st April 1989. The bank of the appellant in the present case is a registered cooperative society which was earlier known as “Punjab State Cooperative Land Mortgage Bank Ltd.” The bank is formed with the primary objective of providing long-term loans to farmers and their communities, with the aim of protecting them from the clutches of money lenders. In fulfilling its objective, the appellant bank receives its funding for the purpose of its functioning by way of loans from the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) as per the norms laid down. The Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. consists of a two-tier structure comprising of “Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd.” at the Apex level (SADB) and “Primary Agricultural Development Bank Ltd.” (PADB) at the grass root level. The function of these two banks is to ensure timely delivery of credit to the farmers, who are its members and are direct beneficiaries of various schemes which provide such farmers long-term and short-term loans.

Scheme applicable to Bank before the year 1989

Before 1989, the employees of the appellant bank were covered under the Employees Provident Fund and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1952 (hereinafter referred to as “Act, 1952). The appellant bank duly adhered to the provisions of the scheme and a regular contribution was being paid by both the employer and the employee towards the pensions scheme. In a letter dated September 22, 1988, the Department of Finance, Government of Punjab, expressed its agreement to follow the recommendations of the Punjab Pay Commission to bring employees working for various public sector utilities and state-aided institutions under the State Pension Rules. The purpose of the inquiry was to get input from the relevant organisations regarding, among other things, the additional financial burden associated with each case and whether the organisation or organisations could afford the additional liability out of their own resources. These recommendations were presented to the bank administrator, who decided to implement the recommendations of the State Government by resolution dated June 22, 1989.

Scheme applicable to Bank from the year 1989

As a result, the Pension Scheme for employees and officers in the common cadre was introduced on 1st April 1989. In order to pursue this, the appellant bank wrote the Registrar of Cooperative Societies, Punjab, on 27th June 1989, requesting permission to implement a pension scheme for its workers who fall under the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Land Mortgage Banks Service (Common Cadre) Rules, 1978. The Registrar of Cooperative Societies, Punjab, approved the launch of the proposed pension scheme of the appellant bank to its employees on 7th February 1990, by an official communication. In accordance with this, the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Land Mortgage Banks Service (Common Cadre) Rules, 1978 were amended, and Rule 15(ii) was added, enabling the Board of Directors to create a pension scheme with the approval of the Registrar Cooperative Societies. In furtherance to it, the amended Rule 15 (ii) came into force with effect from 1st April 1989. For the purpose of reference, Rule 15 (ii) is given as below:

“PROVIDENT FUND: The employees shall be entitled to the benefit of the General Provident Fund as provided in the Employees Provident Fund Act, 1952 and scheme framed thereunder”.

Following the introduction of the implementation of the amended pension scheme, the contribution towards the pension scheme made by the appellant bank and the employees were transferred to establish the Pension Corpus Fund, which allowed the scheme to function. A trust was established by a trust deed dated 24th March 1993, to oversee and successfully implement the scheme.

Changes that took place after the introduction of the new scheme

According to the evidence presented in this case, the appellant bank workers who chose to get a pension became members of the pension scheme and were able to continue receiving benefits after they had opted for the pension scheme until 2010. However, later, the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. started to feel difficulty in providing pensions under this scheme and the said bank found the pension scheme to be unviable on account of financial constraints on the said bank. The Board of Directors of the appellant bank held a meeting on 29th May 2010 in reference to Agenda Number 15 and decided to reconsider the matter of giving pensions to the employees of the bank. The appellant bank decided to seek approval regarding the aforementioned reconsideration of the pension scheme from the Registrar, Cooperative Societies, Punjab.

The Registrar, Cooperative Societies, Punjab issued directions to the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. to review its proposal by way of a letter dated 3rd September 2010. On 30th March 2011, the appellant bank sent the revised proposal regarding the pension scheme concerned to the Registrar, Cooperative Societies, Punjab. Although, the proposal was turned down by the Registrar, Cooperative Societies, the Board of Directors with reference to the Resolution dated 17th August 2012 decided to discontinue the pension scheme and modify the pension scheme to a Contributory Provident Fund with a proposal of one-time settlement. In furtherance to this, the Board of Directors in the exercise of its power vested under Section 84A(2) of the Punjab Cooperative Societies Act, 1961 with the prior approval of the Registrar, Cooperative Societies made an amendment in Rule 15 of the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Land Mortgage Banks Service (Common Cadre) Rules, 1978 and Rule 15 (ii) was deleted dated 11th March 2014.

Many employees had approached the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution due to the non-payment of pension by the appellant bank much before the amendment of deleting Rule 15 (ii) of the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Land Mortgage Banks Service (Common Cadre) Rules, 1978. Out of this case, a number of interim orders were issued from time to time, and at one point it was decided to introduce a one-time settlement proposal, which was provided by the appellant bank on October 16, 2012, in the pending proceedings before the High Court.

However, in reality, a very small number of employees have settled their claims under the one-time settlement, but it is appropriate to note at this point that, during the time the proceedings were pending before the Division Bench of the High Court, Punjab and Haryana at Chandigarh, an order dated January 24, 2014, made it clear that a one-time settlement that has been implemented after obtaining approval from the appropriate authority will not impair the applicant’s or respondent employee’s legal rights, with respect to other remedies. This fact can be further observed in that Rule 15 (ii) was deleted by the appellant bank by an Order dated March 11, 2014, while the proceedings were pending in Letter Patent Appeal before the High Court. The learned Single Judge of the High Court held that the employees of the appellant bank, having served the bank, were covered under the scheme which was applicable at the given time under the “Employees Provident Fund and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1952” (prior to 1989).

By the time the case reached the Division Bench of the High Court, Rule 15(ii) had been removed and an order dated March 11, 2014, had made the adjustment. The Division Bench at the High Court of Punjab and Haryana at Chandigarh took into consideration the fact that the appellant bank had made the decision to introduce Rule 15(ii) after enough deliberation and in such a circumstance, it was a conscious decision of the appellant bank.

The Division Bench of the High Court made certain observations and said that as per the decision of the appellant bank, Rule 15(ii) was introduced. This new rule was enforced on 1st April 1989. However, due to certain financial constraints faced by the appellant bank, the aforementioned rule, that is, Rule 15 (ii) was deleted on 11th March 2014. A large chunk of employees already became part of the said pension scheme. As a result, the right of pension had become a vested or accrued right by the time the new rule was deleted. The deletion of such a rule was against the interest of employees with regard to the entitlement to pension of retired employees.

It may be pertinent to mention that the Regional Provident Fund Commissioner filed various counter-affidavits before the High Court at various points in time, referring to the exemption grant after the Employees Pension Scheme of 1995 became a part of the Act 1952. An unconditional apology was given by the Regional Provident Fund Commissioner for mentioning regarding granting an exemption from the pension scheme as such a mention was factually inaccurate.

On 29th July 2019, the judgement of the Divison Bench of the High Court was challenged by the appellant bank and serving employees. The appellant bank and the serving employee challenged the decision of the Division Bench of the High Court on the ground that such a judgement would have a negative impact on their pension rights in the future. This concern was raised by the employees of the bank to the Supreme Court of India during the proceedings of this case.

Issues raised in the case

There were multiple issues in this case as it was a long-standing matter. They are listed below:

- The primary issue in the case was whether the appellant bank (The Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd.) could withdraw or discontinue midway the pension scheme which was originally planned to be effective till 2010.

- The second question before the court was whether such action on the part of the appellant bank regarding the pension scheme is violative of Article 14 and Article 16 of the Constitution of India.

Arguments of the parties

Arguments by the Appellant

The Employee Provident Funds Scheme of 1952 and the Employee’s Pension Scheme of 1995, according to the EPFC, are both intended to provide a basic level of old age/terminal social security. Both of these schemes do not completely eliminate the right of an employee to the entitlement to social security benefits. It is essential to assess the bank’s assurance of providing additional pensions outside of EPF as per the EPFC.

The benefits under the pension scheme can only be understood as an additional benefit and not a substitutionary benefit as the pension system of the bank did not provide for withdrawal benefits, dependent’s benefits, nominee benefits, or children’s benefits. In this sense, the pension scheme is far more limited in its application. Section 17(1C) of the Act, 1952 did not allow its pension scheme to be excluded.

Additionally, the learned counsel for the appellant bank stated that the High Court did not take into consideration the fact that the pension scheme designed by the bank was contingent on approval from the appropriate authority. Although the appellant bank did not apply for approval or exemption from the authority, the fact remains that the retirees were entitled to pension payments until the scheme’s expiration date of October 31, 2013, provided the appropriate authority did not grant their request.

The learned counsel further argued that there will be a payment of double pension, which is illegal in any case, if the employees are allowed to receive a pension under the scheme of the bank after October 31, 2013, in addition to receiving a statutory pension from the Regional Province Fund Commissioner under the Act 1952.

The counsel further argued that the employee is entitled to a pension, but as to how that pension is to be calculated, learned counsel further maintains that no one may assert any vested or accumulated rights. The respondents do not claim that they are not receiving pension payments. It was paid earlier under the pension scheme of the bank, which was established in 1989 and was in effect until October 31, 2013. After that, the workers are eligible to receive a statutory pension under the terms of the Act 1952 through the Employees Pension Scheme 1995.

Therefore the counsel maintained that the consideration of the High Court of the plea of vested right is entirely misplaced. As long as the appellant bank satisfies its statutory liability under the provisions of the Act 1952, which they are required to comply with, the employees are not entitled to claim pension under the scheme introduced by the bank after it stands withdrawn with effect from October 31, 2013. Consequently, no vested or accrued right of the employee has been defeated in any way, and the finding of the High Court to continue the bank pension scheme after it was deleted is not sustainable in law and requires interference by the Supreme Court of India.

In support of his submissions, the learned counsel cited the judgments of Marathwada Gramin Bank Karamchari Sanghatana and Another vs Management of Marathwada Gramin Bank and Others (2011), State of Rajasthan Vs A.N. Mathur and Others (2013), State of Himachal Pradesh and Others Vs. Rajesh Chander Sood and Others (2016) to the Supreme Court of India.

The learned counsel further argued that the pension scheme that the bank introduced later became financially unviable and that the number of retirees compared to the current employees hired after January 1, 2004, is almost three times. If the appellant bank is required to continue paying pensions under the Bank Pension Scheme, the bank will go out of business and will become defunct and the serving employees’ pension contributions will be in vain, and they will receive nothing upon retirement.

The appellant bank also argued that the bank made a low profit in recent years, the appellant bank would have no choice but to close the bank and the bank would become insolvent, in the given circumstances. The appellant bank further argued that in case, such a judgement is enforced, the bank would not be able to pay such an amount to the pension under the contested pension scheme. According to learned counsel, the Regional Provident Fund Commissioner has started distinct proceedings under Section 7A of the Act 1952 for the years, April 1989 to March 2015 and April 2015 to June 2017. These proceedings impose liability on the bank through orders dated August 31, 2017, and September 14, 2015, respectively.

Moreover, the learned counsel further submitted that multiple cases were filed under Section 14B for damages and Section 7Q for interest simultaneously. The demands were raised in accordance with the instructions granted by the authority of the appellant. As per the specified conditions, the compensation has been given to the Regional Provident Fund Commissioner for pension fund contributions, damages, and interest for the months of April 1989 and August 2017. In addition, the appellant has been instructed to pay pensions to retirees under the bank pension programme to employees who were formerly covered by the programme, in accordance with the contested judgement.

The learned counsel further submitted before the honourable Supreme Court of India that in addition to all the aforesaid issues, some employees have settled their accounts under a one-time settlement that was approved by the government. The counsel stated that if the judgement is implemented in rem, the bank will not only suffer significant financial hardship that is otherwise illegal, but it will also practically be a double payment to the employees, which is above and beyond the payment that was admissible to the employees under the statutory pension scheme 1995 under the Act 1952.

Arguments by the Respondent

On the other hand, Mr. P.S. Patwalia, the learned senior counsel for the respondents, argued that it is undeniable that the current respondents, who were writ petitioners before the High Court, are retired employees. The employees became part of the pension scheme under the 1978 Rules. Further, they began receiving pensions under the scheme with effect from 1st April 1989. In the year, 2010, the pension was unilaterally stopped to be given by the to the respondent pensioners without providing any justification. As a result, the retired employees had to file a writ petition before the High Court. The High Court decided that these pensioners are entitled to pension under the scheme. In order to overturn the August 31, 2013, ruling of the learned Single Judge of the Punjab and Haryana High Court, Rule 15(ii) was removed by order dated March 11, 2014. This removal of the rule has resulted in the vested rights of retired employees being taken away, and their service conditions have been changed retroactively to their detriment, which is against Article 14 and Article 21 of the Constitution.

Regarding the Act 1952 scheme, the learned counsel for the respondent further argued that it was not related to the pension scheme introduced by the appellant under its Resolution No. 24 dated June 22, 1989, which took effect on April 1, 1989, and that the appellant bank was not required to seek any exemption under Section 17(1C) of the Act 1952 because it introduced the pension scheme in 1989. The Division Bench held that the right to pension is a vested or accrued right of the retired employees and it cannot be taken away retrospectively in a manner which is detrimental to the interest of those beneficiaries.

The reliance has been placed on the Constitution Bench judgement of this court in Chairman, Railway Board and Others Vs. C.R. Rangadhamaiah and Others (1997) followed by U.P. Raghavendra Acharya and Others Vs. State of Karnataka and Others (2006) and Bank of Baroda and Another Vs. G. Palani and Others (2022).

In addition, learned counsel for respondents argued that one-third of the retirees have already passed away while the case is still pending and that more than half of the respondents are between the age group of 73 and 80 years.

Further, a third of the pensioners had already passed away while the lawsuit was pending, and the appellant bank was the one that voluntarily introduced the pension scheme, and the workers of the respondent have chosen to be controlled by it. They have also chosen not to participate in the Contributory Provident Fund. In the given situation, under no circumstances could the appellant arbitrarily take away the rights granted and vested in the respondent workers, in contravention of Article 14 of the Constitution. As for the one time settlement scheme, learned counsel contends that it was implemented as a temporary solution to address the issue caused by the withdrawal of the pension scheme in accordance with the interim measures issued by the High Court.

Moreover, several employees have accepted the one time settlement scheme because they had no other choice and were living paycheck to paycheck. However, in the interim order passed by the Division Bench, the Division Bench made it clear that the legal rights of the employees would not be affected by accepting the pension scheme and that in the specific circumstances, the money paid to a few employees under the one time settlement scheme is always refundable under the scheme to which they are legally entitled. This particular system of the appellant bank was an established practice for over the past twenty years and had become a vested right of the employee, and thus, it is not permissible for the appellant bank to arbitrarily take away their rights and deny them the benefit of the pension, which has been existing through the 1989 as far as the retirees are concerned.

As per the learned counsel for the Regional Provident Fund Commissioner, Mr Siddharth, the appellant bank is covered by the provisions of the Act 1952. The Act under which the concerned pension scheme comes under consists of three schemes in totality. The other two categories of pension schemes are given as follows:

- The first is the “Employees Provident Fund Scheme 1952 (EPFS)”, which establishes a contributory provident fund under Section 5 and Section 6 of the Act. Under this scheme, an equal contribution has to be made to the provident fund at a specified rate by both, the employers and the employees. The specified rates are periodically announced by the appropriate authorities. Nevertheless, the current monthly wage for employees is 12%.

- The second scheme is the “Employee’s Pension Scheme 1995 (EPS)”, which supersedes the “Employee’s Family Pension Scheme, 1971 (FPS)” and is framed under Section 6A of the Act, 1952. The Family Pension Scheme offered pensions to the dependant of the workers who died in harness.

The learned counsel for the Regional Provident Fund Commissioner also argued that the pension scheme under “Employee’s Pension Scheme 1995 (EPS)” is a comprehension and broader pension scheme as it consists of early retirement, dependents’ pension, and superannuation pension. Its funding comes from transferring a portion of the employer’s 8.33% monthly pay contribution to EPFS into the pension fund. Under EPS, employees do not make contributions. The 1976 Employee’s Deposit Linked Insurance Scheme is the third programme. The bank had requested an exemption from EDLIS under Section 17(2A) and from EPFS under Section 17(1)(b). It was also noted that the appellant bank explicitly mentioned that it did not request for an exemption from the operation of the Employee’s Pension Scheme after 16th November 1995.

Additionally, the learned counsel further stated that the appellant bank did not make a timely contribution under the Employee’s Pension Scheme for the period of 1st April 1989 to 31st March 2015. Further, the appellant bank also failed to make timely deposits for the period of on 1st April 1, 2015 to 6th June 2017 under the Family Pension Scheme. With regards to these defaults into making timely contributions by the appellant bank, separate proceedings were started under Section 7A, followed by damages under Section 14B, and interest under Section 7Q. A provision for the final assessments after giving the appellant bank a chance was also considered.

With regards to the concerns of the serving employees, Mr. Gurminder Singh, learned senior counsel for the employees argued that under the new pension scheme, the serving employees were required to make their own contributions. This comes as an adverse effect on the interest of the serving employees as the contributions made by the serving employees is being used against the payment of pensions to the retired employees. Moreover, there has been constant underfunding of the serving employees by the appellant bank. The actions of the appellant bank indicated that the retiring employees may not be able to receive their pension even after completion of their commitment during the employment. The learned counsel for the serving employees stressed the fact that the pension to the retired employees is being paid at the cost of the serving employees and such an action on the part of the appellant bank is against the interest of the serving employees.

The learned counsel also made an argument stating that the rules and regulations applicable to the serving and retired employees with regards to a pension shall be the same and it should be implemented to all the employees without any unreasonable discrimination. It would be unfair to allow the bank pension plan to continue at the expense of serving employees, depriving them of their legally mandated right to the pension that the bank introduced.

Judgment of the case

The Honorable Supreme Court of India recorded all the material available on record with the assistance of the learned counsel. It was determined that the unilateral amendment to retroactively remove Rule 15(ii) by the bank, which essentially cancelled the entitlement to the pension of the retired employees was invalid and unconstitutional. The ruling reaffirmed that once vested rights have been acquired under an established regulation, they cannot be revoked without going against the equality and right to life guarantees included in the Constitution.

Whether the vested or accrued rights can be divested with retrospective effect by the rule making authority, at any given time?

The Supreme Court of India noted the fact that the respondents are members of the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Limited, Chandigarh. The court said that it is an undeniable fact that they were also members of the Employees Provident Fund Scheme under the Act 1952 before their retirement. The employees and the employer bank were properly adhering to the programme and making the appropriate contributions. Subsequently, the Administrator of the appellant bank decided, by Resolution dated June 22, 1989, to implement the recommendations of the State Government regarding the introduction of the pension scheme in response to the recommendations by the Punjab Pay Commission. As a result, the pension scheme for employees and officers in the Rules 1978 was introduced with effect from April 1, 1989.

As a result, Rule 15(ii) was added after the Rules of 1978 were modified. This action was taken by the Board of Directors with the prior approval of Registrar Cooperative Societies, Punjab. In accordance with this, an option was included in the amendment so that workers who choose to follow the regulations, that is the ‘Pension Scheme’ will be subjected to them. Employees who choose not to follow these guidelines at that point will be subjected to the Act of 1952. All respondent employees were, without dispute, offered the choice to join the pension scheme upon leaving their employment. They did so continuously until 2010, at which point the litigation began when the appellant bank ceased to pay pensions under the terms of the bank pension scheme. While under some circumstances the bank pension scheme will not apply to workers hired on or after January 1, 2004. Later, the bank decided to delete Rule 15(ii) of the pension scheme on 11th March 2014. This decision provided the basis for the grievances of the workers, which they used to challenge the conduct of the bank and take their case to court.

The Supreme Court of India further said that it is the appellant bank that accepted the recommendations of the State Government and put forward two options and solicited it from the employees, as to whether they wanted to opt for a pension scheme which became applicable after the amendment was made under the Rules 1978. The Supreme Court of India further said that the decision of introduction of Rule 15 (ii) was a conscious decision that was great discussion and deliberation. Thus, it could not be justified to nullify the effect of the amended rule and create a circumstance which would lead to defeating the rights which are conferred upon the employee to seek pension under the rules which became applicable with effect from 1st April 1989. Finally, the High Court of Punjab and Haryana at Chandigarh held that the employees are entitled to regular pensions including the pensions under the amended scheme of revised rates of dearness allowance, to all the employees who became members of the pensions scheme under the Rules 1978.

The court further said that the question that emerges for consideration is as to what is the concept of vested or accrued rights of an employee and whether such vested or accrued rights can be divested with retrospective effect by the rule making authority, at the given time.

On these questions, the Supreme Court of India made the following observation. The concept of vested/accrued right in the service jurisprudence and with respect to the pension particularly has been examined by the Constitution Bench of this court incase of Chairman, Railway Board and Others (1997).

The Supreme Court of India said that the decisions made by the Full Bench and those other Benches of the Tribunal are the subject of these appeals and requests for special leave.

A bench of three learned judges from this court heard some of these cases on March 28, 1995, and issued the following ruling. Two questions arise in the present case, that is:

- What is the concept of vested or accrued rights so far as the government servant is concerned and;

- Whether of the two, and to what degree, rules imposed under the proviso to Article 309 or an Act passed under that article may retroactively take away vested or accrued rights.

The Court said that three-judge bench decisions in K.C. Arora vs State of Haryana (1984) and K. Nagaraj vs State of Andhra Pradesh (1985) have been cited as justification for the Constitution Bench decisions in Roshan Lal Tandon vs Union of India (1968); B.S. Vadera vs Union of India (1968); and State of Gujarat vs Raman Lal Keshav Lal Soni (1983). In addition to the two-judge bench rulings in K. Narayanan vs State of Karnataka (1994) and P.D. Aggarwal vs State of U.P. (1987). These justifications were contradicted by the ratio of the aforementioned Constitution Bench rulings. The three judges on the bench confessed openly that they were finding it difficult to settle the aforementioned dispute. As such, it has become imperative to forward the case to a more senior Bench member. As a result, these appeals have been assigned to a panel of five knowledgeable judges. This Court further held in Chairman, Railway Board and Others (1997) that it had already considered the matter.

Whether action on the part of the appellant bank regarding the pension scheme is violative of Article 14, Article 16 and Article 21 of the Constitution of India?

The Supreme Court of India further said that therefore, it can be said that a rule that governs future rights of people who are already employed can be challenged on the grounds of retroactivity as violating Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution. Moreover, the Supreme Court further said that an amendment to a particular rule that results in taking away a benefit that has been already vested can be challenged as violative of Articles 14 and Article 16 of the Constitution to the extent that it operates retrospectively. The terms “vested rights” and “accrued rights” have been used in numerous of these rulings. The aforementioned terms have been used in relation to a right arising under the applicable rule that was requested to be changed with effect from an earlier date. As a result, such an amendment eliminated the advantages granted by the rule that was in existence at that time. As per the ruling, any modification that operates retrospectively and eliminates a benefit that the employee was previously eligible for under the current regulation is considered to be unfair and biased. It is considered to be equally in violation of the rights guaranteed under Article 14 and Article 16 of the Constitution. The Supreme Court of India further observed that the judges on the bench are unable to hold that these decisions are not in consonance with the decisions in Roshan Lal Tandon (1968), B.S. Vedera (1968) and Raman Lal Keshav Lal Soni (1983). The Supreme Court of India said that in these situations, the court is concerned with the pension of the employees that they will get after their retirement. The employees were no longer in the service on the date of issuance of the impugned notifications. It meant that on the day the impugned notices were sent, the respondents had departed from their position. The Supreme Court of India then further made an important observation. It held that the modification to a regulation with regards to its future applicability is unrestricted. The Supreme Court of India clarified that the employees who were out of service and had already retired on the day the impugned notices were sent are covered by the amendments.

Precedents referred

U.P. Raghavendra Acharya and Others vs. State of Karnataka (2006)

The issue that later came up for consideration in U.P. Raghavendra Acharya and Others vs. State of Karnataka (2006) was whether the appellants who benefited from the revised pay scale that went into effect on January 1, 1996, could have had their retirement benefits computed with that effect for pension calculation purposes taken away from them. In that regard, this Court noted the following when reviewing the structure of the Rules and depending on the Constitution Bench Judgement in Chairman, Railway Board, and Others vs C.R. Rangadhamaiah (1997).

In the aforementioned case, one of the rules regarding pension schemes read as below;

“A pensionable; claim by a railway servant to pension is regulated by the rules in force at the time when he resigns or is discharged from the service of Government.”

The respondents in these cases are the employees who retired after January 1, 1973, but before December 5, 1988. Rule 2301 of the Indian Railway Establishment Code states that the employees have the right to have their pension calculated using Rule 2544. This is because the aforementioned rule was in effect at the time of their retirement. At that time, the calculation as per the aforementioned rule stated that while calculating average emoluments for the purpose of determining the amount of pension and other retiral benefits, Running Allowance, up to a maximum of 75% of the other emoluments, had to be considered. The amended Rule 2544 by the impugned notifications dated December 5 1988, takes away the aforementioned right of the employees to have their pension computed based on their average emoluments as calculated. Specifically, the maximum limit is now only 55% from April 1, 1979, down from 75% from January 1, 1973 to March 31, 1979, and 45% from January 1, 1973 to March 31, 1979. As a result, the respondents were receiving less amount of pension in compliance with the regulations in place at the time of their retirement.

The Supreme Court of India while referring to this judgement said that the different group of retired employees who were subject to a different set of regulations may be refused to be granted pension benefits under the new scheme while implementing it. A class of employees may also be refused to be granted pensionary benefits if it is not contradictory to any law at the time being.

On the other hand, the arguments of the appellants were of different nature. They said that the updated pay scales have helped them and are not a problem to them. The University Grant Commission and the Central Government have recommended that the State of Karnataka extend the advantages of the Pay Revision Committee in their favour.

A Constitution Bench of this Court rendered the following opinion in Chairman, Rly. Board vs C.R. Rangadhamaiah (1997). In addition to violating the rights then available under Articles 31(1) and 19(1)(f), the impugned amendments, to the extent that they have been given retrospective operation, are also violative of the rights guaranteed under Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution on the grounds that they are unreasonable and arbitrary since the said amendments in Rule 2544 have the effect of reducing the amount of pension that had become payable to employees who had already retired from service on the date of issuance of the impugned notifications, in accordance with the provisions contained in Rule 2544 that were in force at the time of their retirement. The appellants were no longer on active duty. Because of this, the State was unable to retroactively change the statutory regulations in a way that would have negatively impacted their pension.

Bank of Baroda and Another vs G. Palani (2022)

While referring to the case of Bank of Baroda and Another vs G. Palani (2022), the court mentioned that the issue at hand in this case was to determine whether or not the employees who left the employment or deceased while still in employment between 1st April 1998 and 31st October 2022, who have a vested or accrued right over the pension scheme and benefits of pensions subsequently. In this regard, this Court made the following observations while acknowledging the viewpoint taken in the case of Chairman, Railway Board and Others (1997).

The Supreme Court of India said that the regulations that were in effect until 2003 would still remain enforced. In their opinion, the addition of Explanation (c) to Regulation 2(s) in the aforementioned regulation did not have the effect of changing the regulations pertaining to pensions, which were contained in Regulation 38 read in conjunction with Regulations 2(d) and 35 of the Regulations of 1995. Otherwise, it could not have acted retroactively and taken away vested rights, even if it had the effect of changing the salary and benefits “average emoluments”, as stated in Regulation 2(d). If not, it would have likewise constituted an arbitrary use of force. Furthermore, the so-called Joint Note of the Officer’s Association had no statutory force because, as the Officer’s Association admitted, the Industrial Disputes Act’s provisions did not apply to it, and the joint note lacked statutory support. It was also not permissible to deny officers who retired from 1.4.1998 to December 1999 and beyond the benefits of the Regulations, nor to forgo those benefits. Therefore, no estoppel is considered to have been formed by the Joint Note that has been relied upon. Estoppel in opposition to the application of legislative requirements does not exist. The Joint Note lacked legal effect and could not have violated the spirit of the Act of 1970’s regulations or the fundamental terms of employment as outlined in those regulations. As established by this Court in Central Inland Water Transport Corporation Limited & Anr. vs. Brojo Nath Ganguly & Anr., (1986) and Delhi Transport Corporation vs. D.T.C. Mazdoor Congress, (1991), they could not have been tampered with arbitrarily.

Marathwada Gramin Bank Karamchari Sanghatana and Another case (2011)

The court then referred to the case of Marathwada Gramin Bank Karamchari Sanghatana and Another case (2011), which was mentioned by the appellant bank while presenting their arguments. The court said that the subject under consideration in the Marathwada Gramin Bank Karamchari Sanghatana and Another case (2011) concerned the provident fund. The Marathawada Gramin Bank launched a provident fund system which was built on higher contribution rates than those required under the Employee’s provident fund programme. Moreover, Section 17(1) granted statutory recognition to the provident fund which has higher contribution rates. However, after some time, the Marathawada Gramin Bank switched back to the rates required by EPFS paragraph 26 after discontinuing its provident fund system due to financial unviability.

State of Himachal Pradesh and Others vs Rajesh Chander Sood (2016)

The appellant bank also made reference to the case of the State of Himachal Pradesh and Others vs Rajesh Chander Sood (2016). Regarding the ruling in State of Himachal Pradesh and Others vs Rajesh Chander Sood (2016), it was a case in which the State of Himachal Pradesh framed a different scheme for the Himachal Pradesh Corporate Sector Employees Pension (Family Pension, Commutation of Pension and Gratuity) Scheme, 1999 in addition to the one under the terms of Act 1952. This pension scheme had came into existence on 1st April 1999. However, it was deleted on 2nd December 2004 before the employees could have taken any benefit of such a pension scheme. This took back the vested or accrued rights of the employees. The dispute emerged as to whether, even after being revoked by a subsequent notification dated December 2, 2004, the contingent right granted to the employee upon their initial opting under the 1999 system was binding or irreversible.

State of Rajasthan vs A.N. Mathur (2014)

In the State of Rajasthan vs A.N. Mathur (2014), the University, an autonomous body established under the Act’s provisions, introduced a pension scheme through a resolution. This pension scheme was introduced without any prior approval from the Chancellor, or the Governor of the State in accordance with Section 39 of the Act and Resolution 39 of the University. In the given circumstance, the Chancellor never gave his or her approval. Accordingly, the introduction of such a pension scheme without any prior consent from the concerned authorities was considered to be unauthorised and invalid. The implementation of such a pension scheme was stayed.

Regarding the submission of the appellant, which cited the financial difficulties of the bank as justification for the challenged amendment, stating that it might not be feasible to continue the pension grant going forward, it is sufficient to say that the rule-making body was presumed to be aware of the consequences of the specific piece of subordinate legislation and once the bank made a deliberate decision to introduce the pension scheme with effect from April 1, 1989, after receiving approval from the Punjab government and the cooperative’s registrar, it can be assumed that the relevant authorities were aware of the 40 resources from which the funds are to be created for paying its retirees. Furthermore, just because the bank was later unable to hold financial resources at its command to its retirees does not justify withdrawing the plan retroactively, which would be detrimental to the interests of the employees who not only became members of the scheme but also regularly received their pension until at least 2010 until the disagreement emerged between the parties and entered into litigation.

Critical Analysis

The Supreme Court of India provided a detailed explanation of the reasoning it applied in delivering the judgement in this long-standing matter. The Supreme Court of India believes that the appellant bank would not be able to use the lack of financial resources as a justification to deny the vested rights to the employees that they have accumulated, as it is a major part of their socio-economic security. A pension scheme is an assurance in terms of socio-economic security. Such pensionary benefits are not bounty and cannot be turned down without any valid ground. The Supreme Court directed the appellant bank to meet its obligations by paying pensions to its employees who retired under the previous pension scheme.

As per the serving employees are concerned, the Supreme Court of India further said that they have no locus standi to the issue in this case. The court further clarified that the concerns put forth by the serving employees are totally unfounded because the contributions of the employer and employee are made under the Employee’s Pension Scheme (EPS) of the Act 1952, which is applicable to all currently employed employees. Additionally, they are eligible for pension benefits in accordance with provisions of the 1952 Act.

With respect to the concerns regarding the payment of their contributions, the Supreme Court of India held that it will not be modified in any way for the purpose of paying pensions to respondents or retirees, who are entitled to receive their pensions under the terms of the pension scheme to which they belong. The appellant bank will be responsible for setting aside funds and paying retired employees who wish to receive pensions under the scheme that was in effect at the time they joined and began receiving benefits under it.

The Supreme Court of India also said an essential element of the dispute and stated the following;

“Before we part with the judgment, we cannot be oblivious of the situation that the complaint of the employees that they are not being paid their pension since 2013, at the given time few employees have been given benefit of one time settlement as introduced by the bank as an interim measure which was subject to their rights being preserved, in the pending litigation, taking 42 grievance of the either party into consideration, the financial constraints of the bank and the rights of the employees who are entitled to get pension under the bank pension scheme, we consider appropriate to observe that so far as the arrears towards element of pension to which the retired employees are entitled for, the appellant bank is at liberty to pay arrears towards pension upto 31st December, 2021 in 12 monthly instalments in the next one year by the end of December, 2022 and those employees who have accepted payment under one time settlement at a given point of time, what is being paid to them is always open for adjustment against arrears of their due pension.”

The Supreme Court of India further said that the bench deemed it appropriate to note that, in so far as the retired employee’s pension arrears are concerned, the appellant bank is free to settle any arrears until December 31, 2021, in twelve monthly instalments over the course of the following year, ending on December 31, 2022. Additionally, employees who have accepted payment under a one-time settlement at any given time are always eligible to have their benefits adjusted against arrears of their due pension. If there are still unpaid debts, they must be settled in twelve monthly instalments. The court stated that the pensions are to be paid to all the employees who are part of the pension scheme of the appellant bank at the same time, which is, from the month of January 2022.

The Supreme Court of India further clarified that the appeals with regard to the complaint of the appellant bank against orders made in accordance with Sections 7A, 14B, and 7Q of the Act 1955 are not the topic of dispute in the current proceedings. The appellant may seek any suitable legal action if they feel wronged. Therefore, the Supreme Court rejected the appeals with the previously mentioned remarks. The court dissmed all the applications in progress, if any.

The decision of the Honourable Supreme Court in this case has broader implications for the cooperative banks and the employees working for them throughout India. It serves as a caution for employers against any modification or amendments in the existing schemes or rules that are arbitrary and underlines the necessity for an institution to adhere to the basic principles of fairness, reasonableness and non-retrospectively. The Cooperative banks are required to now ensure that any changes to any benefit schemes of their employees are prospective and not remove any rights that has already been granted or vested to the employees.

Laws involved in the case

Principle of Reasonableness and Fairness

One of the famous Scholar in laws of natural justice, Abbott vs Sullivan (1952) once said;

“The principles of natural justice are easy to proclaim, but their precise extent is far less easy to define”

The Indian Constitution serves as the basis for the scope of the principle of reasonableness. It says that the grounds for the discrimination must be legitimate. Article 14 of the Constitution provides a foundation for creating acceptable categorization among various persons or groups within society. This conveys the idea that people are all unique from one another. Any comparable treatment is thus considered unfair and unjustifiable. In pursuance of this, it becomes necessary for the State to act as a guardian of such rights. Therefore, the concept of ‘intelligible differentia’ enables the legislature to pass such classified legislation that enables the protection of certain classified groups in a reasonable manner.

Reasonable classification finds its basis in the concept of intelligible differentia. It comprises identifying a group of people who share common characteristics. In other words, the distinction can be made on the fact that the people within a classified group are different from the ones outside the other groups. Furthermore, a causal link needs to be established between the reasonable classification and the rationale behind the adoption of any policy favouring such a classified group. As per Article 13 of the Constitution of India, any legislation on the basis of a class of people is not allowed. However, it does not restrict the parliament from classifying people, things, and transactions in a legitimate manner in order to accomplish certain goals. Such a categorization must be based on significant, genuine distinctions and cannot be contrived, arbitrary, or evasive. The purpose that the legislation aims to attain must have a fair and just relationship with it. As in the case of Saurabh Chaudhari vs Union of India (2004), the Supreme Court of India mentioned the following about the classification of reasonableness. It said that the classification of reasonableness contains two requirements:

- The categorization must be based on intelligent differentia that distinguish the grouped individuals or items apart from those that are excluded from the group.

- The disparity has to be reasonable related to the desired outcome of the action. Differentiation based on classification and the purpose of the act is two different things.

- It is imperative that there exist a connection between the purpose of the act and the basis of classification. When a legitimate basis cannot be found for a classification made by the legislature, then such discrimination shall be declared discriminatory and unfair.

Now the concept of fairness under the Constitution of India is much broader than what it looks at once. The entire essence of the principle of natural justice is based on the concept of fairness and equality. The principles of natural justice are a tool to establish the principle of fairness in any legislative, administrative or judicial conduct. The principle of natural justice is given below which encompasses the essence of the principle of fairness;

The principle of ‘Nemo Judex In Causa Sua, or the Rule Against Bias’ is one of the central pillars of the concept of the principle of fairness and natural justice. Bias is defined as an operational prejudice, whether conscious or unconscious, against a party or topic. Consequently, the anti-bias rule removes any factors that can unfairly influence the ruling of a judge in a particular case. According to this rule, the judge must be impartial and make a decision that is based only on the information that is at hand. According to human psychology, people seldom make choices that are not in their best interests; consequently, in situations where they have an interest, people are unable to come to an unbiased judgement. As so, the proverb becomes: “No one is fit to judge another person.”

Another central principle in it is the principle of Audi Alteram Partem (Rule of Fair Hearing)

In essence, it says that no one may be punished or found guilty by the court without first having a fair opportunity to be heard. There are three Latin words in it. In a great number of jurisdictions, the majority of cases remain unresolved without receiving a fair hearing. It indicates that the trial must be conducted in a fair manner. Further, during a proceeding in a trial, all the parties must have an equal opportunity of being heard and present their relevant evidences. It is based on the principle that no one should be punished arbitrarily. It is an important pillar of the principle of natural justice. It also says that an accused should be provided with the information regarding the allegations raised ahead of time. This would enable the accused to prepare their defence at an appropriate time.

The foundation of the principle of fairness is ‘Equity’. It is based on the moral conscience and the idea of treating everyone fairly in accordance with natural law. Article 14 of the Constitution guarantees equality, and the court in Maneka Gandhi v Union of India (1978) said clearly that Article 14 upholds the notion of equality and reflects the principles of natural justice.

The Supreme Court decided in Suraj Mall Mohta and Co. vs A. vs Visvanatha Sastri (1958) that the assessment procedure of the income-tax officer qualifies as judicial proceedings. Before reaching a decision, all prerequisites for these legal actions must be satisfied as per the principle of equity and fairness. The income-tax officers have the right to inspect and review any record or document that the assessee may possess before asking to provide any evidence in rebuttal. There are no express provisions in the Income Tax Act that impair this entitlement. In the case of Manohar Lal Sharma vs. The Principal Secretary & Ors. (2014), it was held that in cases when there is an allegation raised by an anonymous complaint, there must be strict adherence to the principles of natural justice. In these situations, the accused must be given a fair opportunity of being heard.

Doctrine of Legitimate Expectation

The word “Legitimate Expectation” doctrine refers to anything that a person can reasonably or legitimately anticipate from another person without that person having any legal rights associated with it. The word “Legitimate Expectation” has no legal definition according to any statute. A person’s hope or desire to get a favourable order, motivated by prior precedent or encouraged by counsel, is known as a legitimate expectation. A valid expectation provides the petitioner with the standing to request a judicial review.

This doctrine has broad implications as it is based on the concept that a promise which is reasonable cannot be refused to be fulfilled subsequently at the time when the promise is supposed to be fulfilled. In other words, it is based on the concept that a promise must be kept. The doctrine of legitimate expectation also finds its basis in the principles of natural justice, social justice, reasonable, fairness, non-arbitrariness and fiduciary duty. According to the doctrine of legitimate expectation, even when a person does not have a private law right to obtain a certain treatment, he may have a legitimate expectation of receiving a right from an administrative body. He could reasonably anticipate obtaining the advantage or privilege even in situations in which he lacks the necessary legal rights. A promise or an established custom that the applicant has a reasonable expectation will be the basis for such an expectation, as well as the expectation that it will be applicable to him. The Court or Tribunal can step in and defend such a person if his legitimate expectation is not met, by enforcing rules that are comparable to the principles of natural justice and fair play.

In India, this doctrine was further evolved in the case of ‘Madras City Wine Merchants vs Tamil Nadu (1994)’, which gave essentials for this doctrine to be applicable. The Essentials are:

- If there was some explicit promise or representation made by the administrative body.

- Such explicit promise or representation was clear and unambiguous.

- There was an existence of a consistence practice in the past that the person relied on for having a reasonable expectation to operate in the same way.

However, in the case of ‘Food Corporation of India vs Kamdhenu Cattle Feed Industries (1992)’, the Honorable Supreme Court of India has observed the following as a cautionary approach and a balancing approach between the power of the court to judicial review in cases of alleged violation of the doctrine of legitimate expectation:

“There is no unfettered discretion in public law. A public authority possesses powers only to use them for public good. This imposes the duty to act fairly and to adopt a procedure which is ‘fair play in action’. Due observance of this obligation as part of good administration raises a reasonable or legitimate expectation in every citizen to be treated fairly in his interaction with the State and its instrumentalities with this element forming a necessary component of the decision-making process in all State actions. To satisfy this requirement of non-arbitrariness is a state action, it is therefore, necessary to consider and give due weight to the reasonable or legitimate expectations of the persons likely to be affected by the decision or else that unfairness in the exercise of the power may amount to an abuse or excess of power apart from affecting the bona fides of the decision in a given case. The decision so made would be exposed to challenge on the ground of arbitrariness. Rule of law does not completely eliminate discretion in the exercise of power, as it is unrealistic, but provides for control of its exercise by judicial review.”

Constitutional Rights with respect to the issues in the case

Article 14, Article 16 and Article 21

The Supreme Court of India emphasises much upon the general principles of natural justice. It mentioned that any amendment with retrospective effect shall not be such that prejudice the vested or accrued right of a person. Any such retrospective amendment would be deemed to be a violation of the rights protected by Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution. In the present case, the pension scheme of the appellant bank was established on April 1st, 1989. Employees were provided with an option to join the pension scheme as per their choice. Several employees opted for the aforementioned pension scheme. In accordance with this, pension payments were made to the respondent employees without interruption until 2010. After 2010, the bank started to face financial constraints in making payments towards pensions. Due to this reason, the aggrieved employees filed a writ petition in the High Court. The Supreme Court further noted the fact that the bank later withdrew the pension scheme by deleting Rule 15 (ii) through an amendment dated 11th March 2014. This amendment was enforced on 1st April 1989. The Supreme Court further observed that there is no doubt to the fact that the aggrieved employees have a vested or accrued right to pension. The court further stated that any amendment to the existing pension scheme having a retrospective application in such a manner as to prejudice the interest of the employees is unquestionably a violation of both Article 14 and Article 21 of the Constitution.

To make its observation clear, the Supreme Court of India explained how such a retrospective application is against the ‘Legitimate Expectation’ of the employees. The court said that at the time when one joins a service or employment, it builds a certain level of expectation on the part of employees with regard to the benefits from the employment as per the terms and conditions of the service. The court also gave an example and said that a senior employee of an organisation may reasonably expect to be promoted to a higher post, based on his experience and qualifications. In a similar fashion, an employee who enters into a service with a particular scheme for pensionary benefit can reasonably expect such benefit to be received at the appropriate time. However, if there is any change to such expectation with regards to pension benefits, promotion or the age of retirement, then such change must not be against the interest of the employees, whether working or retired.

At the same time, if such a benefit which already existed throughout the employment of an employee has been taken away by amending a rule to have a retrospective effect is undoubtedly an infringement of the rights of those employees. This is a clear violation of the fundamental right guaranteed under Article 14 and Article 16 of the Constitution of India.

Conclusion

In the realm of service law, the ruling of the Supreme Court of India sets a noteworthy precedent, especially with regard to pension schemes for the employees of the cooperative bank. This decision demonstrates the dedication of the judiciary in upholding the vested or accrued rights of employees and making sure that retrospective amendments do not unfairly deprive accrued benefits.

The Supreme Court of India underlined the principle that amendments that have retrospective effect and eliminate advantages that employees have previously received are in violation of Articles 14 and 21 of the Indian Constitution. The Supreme Court of India distinguished vested rights from reasonable expectations in an uncomplicated way. According to the regulations in effect at the time of their employment, employees might reasonably expect benefits that they had entered with an expectation of certain benefits as per the terms and conditions of the employment, in such a situation, such reasonable expectation is to be honoured as well. The retrospective removal of such benefits is unfair and arbitrary for the employees who have planned their retirements around these reasonable expectations. The case serves as an example of the responsibility of the judiciary to closely examine legislative and administrative measures that retrospectively change employment conditions to the disadvantage of employees.

The ruling establishes a precedent requiring a thorough analysis of the constitutionality of such acts. The Supreme Court of India reaffirms the notion that legislation or modifications affecting accumulated benefits must pass the reasonableness and fairness test by declaring the retrospective amendment to Rule 15(ii) unlawful. This ruling affects cooperative banks and the people who work for them throughout India. It highlights the need for organisations to uphold the values of equity and non-retrospective and acts as a warning against the willful alteration of employee perks. The decision of the apex court, that is, the Supreme Court of the country to invalidate the constitutional validity of the retrospective amendment of Rule 15 (ii) upholds the principles of reasonable expectation and fairness by stating that laws or amendments having an impact which is detrimental to the benefit accrued must pass the test of reasonableness and fairness. The order of the Supreme Court of India to pay the arrears of pension up to December 2021 in instalments provides immediate relief to the affected retired employees. This comprehensive approach by the Supreme Court of India has not only addressed the issue of financial constraints of the bank but also ensured that the rights of retired employees are protected.

Therefore, ‘The Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Cooperative Societies and Others (2022)’ stands as a landmark judgement in the context of service law and the rights of the employees. It sends a clear message that the judiciary is not going to tolerate any attempts to undermine the rights and benefits that the employees have legitimately earned by way of their rights under the terms and conditions of the employment. By striking down the retrospective amendment that was in violation of the constitutional rights guaranteed under Article 14, Article 16 and Article 21 of the Constitution of India and upholding that the financial burden on the bank cannot be taken as a valid ground for amending the ruling taking away the rights already vested or accrued with the employees of the bank, the Supreme Court of India has once again reaffirmed its role as a guardian of the constitutional right of the people.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is any retrospective application of a law or a rule constitutional as per the fundamental rights guaranteed under the Constitution of India?

The Supreme Court of India in the case of “The Punjab State Coop. Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Coop. Societies and others, (2022)” held that any amendment to a right already granted or, in other words, a vested or accrued right cannot be amended in a manner to take away such vested or accrued rights. Any such amendment to existing rules would be unconstitutional and violative of Article 14, Article 16 and Article 19 of the Constitution of India.

What effect did the decision of the Supreme Court of India in the case of “The Punjab State Coop. Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Coop. Societies and others, (2022)” have on the retired employees of the State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank?

With respect to the retired employees of the State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank, the decision of the Supreme Court of India restored their pension payments. The Court ordered the bank to pay the pension arrears up until December 2021 in stages to the affected retired employees, giving them immediate financial relief. The ruling preserved the entitlement of employees to their vested pension payments.

What was the central dispute in the case of “The Punjab State Coop. Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Coop. Societies and Others (2022)”?

The main question, in this case, concerned the constitutionality of the retrospective amendment by the Punjab State Cooperative Agricultural Development Bank to its pension scheme, which essentially eliminated the payments of pensions to retired employees. The Court looked into whether this change infringed upon the rights of the employees as stipulated in Articles 14 and 21 of the Indian Constitution.

What are the constitutional principles referred by the Supreme Court in its judgement in the case of “The Punjab State Coop. Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Coop. Societies and Others (2022)”?

The Supreme Court of India referred to the fundamental principles of equality and the right to life under Articles 14 and 21 of the Indian Constitution. The Court emphasized that the vested rights, once accrued, cannot be arbitrarily taken away without violating these constitutional guarantees. The judgment placed significant emphasis on the doctrine of fairness, the doctrine of non-retrospectivity, and the protection of legitimate expectations.

What greater implications does this ruling have for cooperative banks in India?

This ruling has wider ramifications for Indian cooperative banks, such as a clear duty to uphold the vested rights of its staff members and refrain from making retrospective amendments that might impair any such rights. Any modifications to employee benefits or pension schemes must be prospective and compliant with constitutional requirements, according to cooperative banks. This ruling establishes a precedent that emphasises the responsibility of the judiciary to defend employee rights from unreasonable administrative acts.

What does the phrase vested rights mean, and how significant are they in this particular instance?

Vested rights are those that have been bestowed and are now unchangeable. In this instance, the vested rights relate to the pension benefits that, under the terms of the current regulations, the employees were entitled to upon retirement. Because once given, these rights cannot be revoked or changed in a way that would be detrimental to the employees, which makes them extremely important. Protecting these rights is crucial to ensuring justice and legal clarity for employees, as the Supreme Court determined that the retrospective amendment that removed these vested rights was unconstitutional.

Is the ruling in the case of “The Punjab State Coop. Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Coop. Societies and others (2022)” to extend to benefits other than pensions received by employees?

Yes, the rules set forth in this judgement also apply to various forms of employment advantages and not only pensions. A wide range of employment law issues can benefit from the Supreme Court’s emphasis on upholding procedural fairness, safeguarding legitimate expectations, and preserving vested rights. Employers must follow a fair and transparent procedure and make sure that any changes they make do not retrospectively impair the vested rights of their employees whether it comes to gratuities, provident funds, promotions, or other entitlements.

What is the importance of procedural fairness reflected in the case of “The Punjab State Coop. Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Coop. Societies and Others (2022)”?

Procedural fairness was a major factor in the ruling of the Supreme Court in the case of “The Punjab State Coop. Agricultural Development Bank Ltd. vs The Registrar Coop. Societies and others (2022)”. All modifications to the terms and conditions of service, particularly those that impact vested rights, must adhere to due process, the Court emphasised. Before making such modifications, this entails giving sufficient notice, a chance for representation, and a fair hearing. The Court concluded that the retrospective amendment of the pension scheme by the bank was arbitrary and unlawful in part because the bank disregarded these procedural protections.

In this case, how did the Supreme Court interpret the meaning of “legitimate expectation”?

In this instance, the term “legitimate expectation” refers to the expectations that workers had about their pension benefits based on the regulations in effect at the time of their enlistment. The Supreme Court recognised the rightful expectation of honouring these promised rewards for workers who had scheduled their retirements around them. The protection of reasonable expectations under service law was strengthened by the retrospective change that disregarded these expectations, which was viewed as a violation of administrative decorum and justice.

References

- https://www.taxmann.com/post/blog/opinion-doctrine-of-legitimate-expectation-meaning-concept-its-application#:~:text=Legitimate%20expectation%20is%20the%20hope,doctrine%20in%20the%20taxation%20matters.

- https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/rules-taking-away-vested-rights-employees-retrospectively-violate-articles-14-21-constitution-supreme-court-bank-pensioners-case-189300

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals, and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications