This article is written by Komal Kumari, a 4th-year student of B.A. LL.B. in Lloyd Law College, Greater Noida. The article focuses on the various torts affecting contractual and business relations.

Table of Contents

Introduction

There are various wrongs that affect the contractual and business relations, these are the acts that are done knowingly without any lawful justification for the sole purpose of interfering and affecting the contractual and business relations. The interference into contractual and business relations are done through these torts:

Inducing Breach of Contract

Any act which is done intentionally without any lawful justification to induce a person to make a breach in the existing contract whereby the other person in the contract suffers damage. The case of Lumley v. Gye,118 Eng. Rep. 749 (K.B. 1853), is an important judgment on this point, as earlier this rule did not apply to other contracts although a master could bring an action against the person who had wrongfully deprived him of the services of his servant; this case brought the turning point in this field of law and any inducement to make a breach of contract was hereby recognized as an independent tort. In this case, a famous operatic singer – Johanna Wagner, was having a contract to sing for the plaintiff. The defendant induced her into breaching the contract by paying her a large amount of money to sing for him rather than the plaintiff, the defendant was held liable.

A tortious act of affecting a contractual or business relation through inducement can be committed in various ways.

By doing certain acts which if done by one of the parties of the contract would have resulted in the breach of the same

Knowingly performing such acts, which if done by one of the parties to the contract, would have resulted in the breach of contract. The decision in the case of G.W.K. Ltd. v. Dunlop Rubber Co. Ltd. explains this kind of interference. The plaintiff G.W.K Ltd. were the manufacturers of cars who were having a contract with A. Co. that the cars manufactured by the former were to be fitted with the tyres manufactured by the latter whenever the cars were sent to exhibitions. When the cars were sent to an exhibition, Dunlop Rubber Co., who was aware of the above-mentioned contract, secretly replaced the tyres from two cars with the tyres of their manufacture. They were held liable towards G.W.K. Ltd., for trespass to goods and towards A. Co. for interference with the contract.

By doing a certain act which renders the performance physically impossible

By doing certain acts because of which the performance of the contract is physically impossible, i.e., removing the tools which are required for the performance of the contract or physically detaining one of the parties to the contract, with the sole purpose of preventing the performance of the contract.

By direct inducement

An act by defendant through which he is offering some kind of temptation to one of the parties of contract for making a breach of his contract, i.e., by making some threat of harm if the contract is kept alive, for instance, a threat of strike until and unless the plaintiff is dismissed or by offering some higher remunerations to a servant than he is already receiving under the existing contract. If the defendant has given a mere advice, then it would not be actionable, i.e., if a person breaks his/her contract because of some medical advice, or suppose a girl breaks her contract of marriage due to her parent’s advice, both these actions are not liable for inducing a breach of contract and no action for the same can be brought against the doctor as well as the parents. However, it is possible that the person breaching the subsisting contract of service or marriage can be held liable for breach of contract.

There are certain qualifications required for breach of contract through inducement:

Persuasion cannot be termed as inducing a person for breach of contract

There is no wrong in persuading a person from not entering into a contract, terminating a subsisting contract lawfully or persuading a person to refrain from entering into a contract. The case of Allen v. Flood, explains this point, in this case, the plaintiffs were shipwrights, who were employed by the shipowners for repairing the woodworks on the ship, but this contract included a clause that their service was terminable at will. Because of some previous grievances, a few ironworkers objected to the plaintiff’s employment there and through their representative, the defendant conveyed the warning to the shipowners that they would go on strike until the plaintiffs were discharged, resulting in the dismissal of the plaintiffs on that day itself. The House of Lords held that since the services of the plaintiffs were terminable lawfully, the plaintiffs had no cause of action howsoever malicious motive the defendants may be having.

Another case that explains this point is Genu Ganapati v. Bhalachand Jivraj, in this particular case, A filed a suit against B with the allegations that B through a suit against A & C, had procured a breach of contract between A and C, he had prevented A from performing the contract, which he had with C. However, it was found that B & C were having another contract regarding the same subject-matter, and what B had done was to enforce his contractual rights. The result of B’s suit was that A was not able to reap the benefits of his contract with C. The court held that A had not been prevented from reaping any benefit from the contract but not from performing the contract and therefore, B was not held liable for interfering with contact or business of A.

Agreements already null & void

If the act is of such a nature that it induces breach of agreements which are already null and void, these are not actionable. Therefore, no action lies for inducing the breach of an infant’s agreement or a wagering agreement which are oppressive and unreasonable in nature.

Justified actions

An action arises when the inducement for making a breach in the contract is done without any lawful justification. An act of inducing the breach with a proper justification is considered a good defense. The case of Birmelow v. Casson, explains this point, in this case it was held that the actions of the members of the actor’s protection society were justified in inducing a theatre manager to break his contract with the plaintiff, as he paid the chorus girls such low wages that they were forced to resort to prostitution. Another example of justified action can be a father trying to persuade his daughter for making a breach of contract of marriage with a scoundrel.

Exceptions of this rule

The exception to this rule was created through the (English) Trade Disputes Act, 1906. As per the Sec. 3 of this Act, the sole ground which indicates that the act of promoting the trade dispute would not be actionable is that it induces some other person to break a contract of employment or it is interfering with the trade, business or employment of some other person to dispose of his capital or labor as he wills.

A similar provision has been provided in the Indian Law under Sec. 18(1) of Indian Trade Union Act, 1926, which mentions that the sole ground that acts as a defense for any officer of Trade Union or any member thereof in furtherance of any trade dispute is that such act induces some other person to break his contract of employment, or that it is an interference with the trade, employment or business of some other person or with the right to act as per his own will on how to dispose of the capital or the labor. Hence, no suit or another legal proceeding shall be maintainable.

Intimidation

Intimidation is an established tort, the threat of doing an unlawful act for compelling a person to do something to his own detriment, injuring or harming himself or to the detriment of someone else. The case of Rookes v. Barnard, is an important judgment recognizing the tort of intimidation-where a person may be threatened to act in a manner injuring some third person. In this case, the plaintiff was employed as a draughtsman in the design office of British Overseas Airways Corporation (B.O.A.C) at London airport. The defendants are the officials of a registered trade union, the Association of Engineering and Shipbuilding Draughtsmen (A.E.S.D.). All members of the union were in a contract with B.O.A.C. that they will not resort to any strike if any dispute arises. The plaintiff resigned from the membership of the union and refused to join the same. His refusal to join resulted in all the members of the union passing a resolution and informing the B.O.A.C. that if the plaintiff was not dismissed, the members of the A.E.S.D. Union will withdraw their labor. As the B.O.A.C. was informed of the resolution by the defendants, the Corporation accented to the threat and dismissed the plaintiff after giving him due to notice. As a result, the plaintiff was not having any remedy against the B.O.A.C., as on their part neither there was any breach of contract or commission of a tort. He brought an action against the defendants for wrongfully inducing B.O.A.C. in terminating his services. The House of Lords held that the threat of withdrawing labor if the plaintiff’s services were not terminated constituted intimidation and since the plaintiff suffered thereby, he was entitled to succeed in his action.

The defendants contended that in order to constitute intimidation, the threatened unlawful act should either be some violence or the commission of a tort and a threat to breach a contract is not enough. The House of Lords rejected this contention and stating that the threat of breaching the contract can be a much more coercive weapon than threatening a tort, particularly when the threat is directed against a company or corporation.

Another contention raised by the defendants was that though there was a threat to break the contract, the plaintiff had no cause of action against the defendant’s as he was a stranger to the contract that was threatened to be broken. The House of Lords rejected this argument too, on the basis that the plaintiff’s action was a tort resulting in damage to himself, rather than the breach of contract. For this, the intimidated party could independently bring a separate action.

For constituting a wrong of intimidation, there should be a threat to do an unlawful act for compelling a person to do something to his own detriment, injuring or harming himself or to the detriment of somebody else. If the threat does not cause any detriment or it is to do something which is not unlawful, there is no intimidation. In the case of Venkata Surya Rao v. Nandipati Muthayya, an agriculturist pleaded that he was unable to pay the arrears of land revenue for which the village munsif threatened to distrain the earrings worn by him if no other movable property was readily available. The village goldsmith was also called for the same but on his arrival, one of the villagers made the necessary payment. It was held that there was no intimidation in this case since the threat was not to do something unlawful and had not compelled the plaintiff to do something to his own detriment or to the detriment of somebody else.

Intimidation under Criminal Law

Intimidation is an offense according to the Sec. 503 of I.P.C., which states that if any individual who threatens another with any sort of harm or injury to his person, property or reputation or to the reputation of anyone in whom that person is interested, in order to cause alarm to that person or to cause that person to do any act which he is not legally bound to do, or to omit to do any act which that person is legally entitled to do, as a means of avoiding the execution of such threat, commits criminal intimidation. For example, a threat delivered by C to B whereby C intentionally causes B to act (or refrain from acting) either to his own detriment or to the detriment of D. The essence of this wrong is the unlawful threats, the threat would be compelling a person to act to his own detriment or to the detriment of some third person. The examples of intimidation are where a person may be compelled to act to his own detriment, by threatening a person with violence if he performs a particular contract, continues his business or passes a particular way.

Conspiracy

An act where two or more persons without any lawful justification, come together with the sole purpose of willfully causing damage to the plaintiff, and an actual damage results therefrom, this would result in the tort of conspiracy. The tort of conspiracy is known as the civil conspiracy. Conspiracy can be termed as a tort as well as a crime.

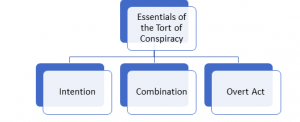

Essentials of the tort of conspiracy

There are three essentials of the tort of conspiracy, the presence of intention is the first and foremost, for a tort to become a conspiracy, the presence of common intention to harm the other person is a must. If the sole purpose of the combination is to defend the trade of those who enter into it or further the trade and not to injure any person, then no wrong is committed and no action will lie although damage has been incurred by the complainant. The aim or the purpose of the coming together or combination must be to cause damage to the claimant, however, the degree of intention to harm may differ (its presence is of utmost importance).

The second essential element is “combination”, which refers to two or more persons coming together for a common purpose of performing a concerted action. The mere presence of similar intention without any combination is not enough for the tort of conspiracy. For example, two different persons Mr. X and Mr.Y having the same intention of harming Mr.W cannot be held liable under conspiracy as they were not combined together even though having the same intention, if with the same intention both the persons have combined together and Mr.X is guarding the door whereas Mr.Y proceeds to harm Mr.W, then this will give rise to the tort of conspiracy.

The third essential is the presence of some overt acts done, that cause damage or harm to the other person. It is an act that is done to fulfill the purpose of the conspiracy. The final stage for the completion of the tort of conspiracy is that some overt act must be done, the completion of the conspiracy is not necessary even if a certain action is carried out in regards to the conspiracy resulting in the damage is sufficient. The tort of conspiracy can be said to be complete if there is a certain element of damage even if the overt act has not been accomplished completely.

When these three essentials are fulfilled then only it can be considered as a civil conspiracy.

Exceptions of this rule

When the motive and aim of persons coming together is for furthering or for protecting their own interest rather than causing damage to the plaintiff, then it can be a valid defense to the act of conspiracy which is a perfect justification of their coming together and still not being liable for their concerted act even though it causes damage to the plaintiff. The case explaining this point is Mogul Steamship Co. v. Mcgregor, Gow and Co., [1892] AC 25, the defendants were firms of shipowners who were engaged in the business of carrying tea trade between China and Europe, they came together and offered reduced freight rate with an intention to monopolize the trade and which resulted in the plaintiff being driven out of the trade, who was a rival trader. The plaintiff brought an action for conspiracy. It was held that the defendants cannot be held liable as their object was a lawful one, i.e., to protect and promote their own business interests and they had used no unlawful means for achieving the same.

Similar decision was taken in the case of Sorrel v. Smith, [1925] AC 700, in this case, the plaintiff withdrew his orders from R, from whom he regularly used to buy his newspapers and started taking it from W. The defendants were the members of the committee of circulation managers of London daily papers, they threatened W of cutting of his supply of newspapers if he still continued to supply the newspapers to the plaintiff. The act done by the defendants was done for promoting their own business interests and thus, they were not held liable. In this case, the following two points were laid down:

- When two or more persons intentionally come together with the sole purpose of injuring another person’s trade or business and their act results in damaging the same, then this act will be actionable as it is an unlawful act.

- If the sole purpose and aim of coming together are to protect and defend the trade of those who enter into it or for the purpose of forwarding the trade rather than injuring someone, then no action will lie even if there has been some sort of damages, as no tort has been committed.

The distinguishing factor in the above-mentioned two situations is that in the first one there is no cause or excuse for the action and is therefore actionable. Whereas in the second one there is an excuse or just cause for the action taken and therefore is not actionable even if the damage has been incurred by the plaintiff.

Case laws in the tort of conspiracy

The actions are for the promotion of the interests of the trade union without any malice- The case of Crofter Hand Woven Harris Tweed Co. Ltd. v. Veitch, [1942] A.C. 435, before this case the law remained obscure regarding conspiracy as tort, this case is a landmark judgment as it firmly establishes that combination of persons with the aim of causing damage to the claimant would be held liable under conspiracy even though the act did would have been a lawful act. In this case, the defendants were a trade union, who instructed the dockers (members of the union), to refuse to handle the plaintiff’s goods without any breach of contract. The aim was to secure economic stability by preventing the competition in the yarn trade and thereby increase the wage prospects of the union members in the mills. It was held that since their actions were not motivated by any malice and were for promoting the interest of its members, there was no conspiracy.

The actions are for the protection of other rights than the economic rights – In the case of Scala Ballroom (Wolverhampton) Ltd. v. Radcliffe, [1958] 1 WLR 1057, CA, it was provided that a combination for protecting other interests than economic interests are also justified. The plaintiffs in this case with the aim to compel the plaintiffs to remove the color bar the defendants (officials of a musician’s union) served a notice to the plaintiff’s statement that if the color bar was not removed, its members (having colored persons) would not be permitted to play orchestra at the ballroom. The court refused to issue an injunction in order to restrain the defendants from making this proposal persuasion to its members.

The aim of the union is to harm or injure the plaintiff rather than the promotion of legitimate interests – In the case of Hunteley v. Thornton, [1957] 1 W.L.R. 321, the defendants, who were the secretary and a few members of the union demanded the expulsion of the plaintiff from the union as the plaintiff (a member of the union) refused to take part in the union’s call for strike. The defendants were held liable for this act as this act was not for the furtherance of some interests but an act actuated by malice and grudges.

An act done for malicious motives – In the case of Quinn v. Leathem, (1901) AC 495 (528), there was the presence of malicious motives on the part of the defendants (trade union officials). The defendants objected to the employment of non-union labor by the plaintiff in his shop, they requested the plaintiff to replace the non–union labor with the members of the union, the plaintiff refused to do that. The defendants approached one of his regular and big customers and forced him to stop buying from the plaintiff. This act was done by the use of threats and force against him, resulting in the customer agreeing to their demand. The plaintiff suffered loss and was held entitled to claim compensation from the defendants.

Act done for the purpose of gaining benefits – In the case of Rohtas Industries Ltd. v. Rohtas Industries Staff Union, (1976) 2 SCC 82, the workmen of two industrial establishments went on strike, this strike was illegal according to the Section 23 read with Section 24 of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, as conciliation proceedings were pending. The Supreme Court had to decide whether the union was liable to pay compensation to the management for the loss incurred by them. Even though the strike was illegal, it was held that the union was not liable as their only purpose was to benefit themselves and not to cause any injury to the management.

Conspiracy under Criminal Law

Criminal conspiracy is governed by the Sections 120A and 120B of I.P.C.,1860, the defines of criminal conspiracy while the latter provides the punishment for the same. As per the definition provided the essentials of criminal conspiracy are, firstly, there should be an object to be accomplished, secondly, a plan or design for accomplishing that object, thirdly, an understanding between the two or more persons, whereby they commit to cooperate for the accomplishment of the object or an agreement for the fulfillment of the object.

Difference between conspiracy as tort and criminal conspiracy

There is a huge difference between criminal conspiracy and conspiracy as a tort. The tort of conspiracy remains uncodified and therefore, guided by the principles of common law, justice, equity and good conscience, and the precedents. But, the offense of criminal conspiracy is well-settled and codified law. An act is actionable as conspiracy under the criminal law if it is merely an agreement between the parties to do any illegal act or a legal act done by illegal means and it is not necessary that the conspirators must have acted in pursuance of their agreement, but the tort is completed only when actual damage has been incurred by the plaintiff.

Malicious Falsehood

Malicious falsehood is the act of making malicious statements related to the plaintiff to some third party which adversely affects the pecuniary interests of the plaintiff. Malicious falsehood is more specifically wrong towards a persons’ business reputation. It is also known as injurious falsehood or trade libel.

A malicious statement made by the defendant regarding the plaintiff’s business being closed down will result in the plaintiff losing his customers this will be termed as a pecuniary loss to the plaintiff. This is a malicious falsehood for which the defendant would be held liable.

The Defamation Act, 1952 (English) provides that it is not necessary to prove the special damage to bring an action for malicious falsehood. Section 3(1)(b) of this act mentions that in an action for slander of title, slander of goods or other malicious falsehood, it is not necessary to prove the special damage:

(b) If the words which caused the action are perceived to be calculated for causing damage in the business, trade, office, profession during the time of publication.

The malicious statement can be further divided into two different forms i.e., slander of title and slander of goods. In slander of title the false and malicious statement about a person’s property or business and might not necessarily be related to his personal reputation, but is related to his title to property, his business or generally to his material interest, for example, a false statement that the defendant has a better title over the plaintiff’s goods or he has a lien over his goods is a slander of title. If the derogatory statement is related to goods, it will be known as slander of goods, for example, making some allegations of the goods being defective that are produced by the plaintiff. The ultimate effect of such a statement is to depreciate the value of the plaintiff’s goods. The law permits making statements, however false and malicious, i.e. when a trader claims that his goods are much better than those of his rival traders, but when there is false and malicious depreciation of the quality of another’s goods, an action can be brought.

Malicious Falsehood distinguished from Defamation

The wrong of malicious falsehood is somewhat similar to that of defamation because, in both these wrongs, the damage is incurred by the plaintiff, the reason being a statement made to a third person. However, these two wrongs are different from each other even if they are having similar properties. In the case of malicious falsehood, it is the pecuniary interests of the plaintiff which are affected, in defamation the plaintiff’s interest affected is the reputation. The essential ingredient in the wrong of malicious falsehood is the existence of an evil motive. Whereas for defamation, malice in the sense of an evil motive is not necessary. Malicious falsehood has a similar property with the wrong of deceit as well, which is, the false statement made by the defendant causes loss to the plaintiff. But these two wrongs can be distinguished on the basis that in deceit the false statement is made to the plaintiff itself and who suffers by acting upon it whereas in malicious falsehood, the false statement is made to a third party resulting in damage to the plaintiff’s pecuniary interests.

Passing off

Passing off is wrong in which a person uses deceptive measures for increasing his sales, to push up his sales in trade and to put up such an impression that these particular goods are of someone else. No person has the right to allow his goods to be showcased as of some other person. In other words, he has no right to represent his goods as somebody else. When a person uses the same name or even a similar name with that of the plaintiff’s goods, by which it appears as if they are the goods supplied by the plaintiff then the wrong of passing off has been committed. Even without proof of any knowledge of an intention to deceive, the defendant will be held liable. It is not necessary to prove the damages suffered by the plaintiff if it is proven that the defendant’s goods were made up as such or described by them which led the ordinary customers to mistake the goods of the defendant as that of the plaintiff.

The aim of the tort of passing off is complementary to the trademark law. It is to protect the goodwill which a commercial has earned so that no one can make the use of the same. In trademark, nobody can interfere with the right by using the mark, the registered trademark is the monopoly of a person. And in the case of passing off, it is the goodwill that is protected, which a trader has earned by his design, goods or trade name.

Passing off distinguished from deceit

- In an action for fraud or deceit, the plaintiff is the one who is deceived by misleading statements, whereas in passing off, the plaintiff is not the one who is deceived but somebody else.

- In an action for deceit, the plaintiff demands compensation in consequence for the loss suffered by him, whereas in an action for passing off, the plaintiff seeks to protect his goodwill, which is being threatened by deception, confusion or the probability of deception or confusion of others.

- The wrong of deceit is constituted when the plaintiff has been deceived, whereas in passing off, the probability of the deception, confusion amongst others is enough. Therefore, in passing off, actual deception is not required to be proved.

- In deceit the action can be brought only when the wrong has been constituted and completed, the action for damages is the only proper remedy available, whereas an action for passing off can be brought even if there is a likelihood of others being deceived or confused, the remedy of injunction is available here.

Elements involved for the tort of passing off

Two elements are required for the tort of passing off:

- A Certain name has been established and became distinctive with regards to the plaintiff’s goods, and

- The use of that name by the defendant was for the purpose of deceiving and has caused confusion and injury to the business reputation of the plaintiff.

Case laws in the tort of the passing off

Nature of the tort of Passing off- In the case of Ellora Industries v. Banarsi Dass, AIR 1980 Delhi 254, Delhi High Court explained the nature of this tort in the following manner:

“The object of the tort of passing off is the protection of commercial goodwill; in order to ensure that no person exploits the business reputation of another. The law protects ‘goodwill’ against encroachment, as it is an asset and a species of property. This tort is based on the economic policy of encouraging enterprises and ensuring commercial stability. This secures a reasonable area of monopoly to traders. And hence, it is complementary to the trademark founded on statute rather than common law. The difference between statute law in relation to the trademarks and passing off action; the registration of the registered mark in itself gives title to the registered owner, whereas the onus of a passing-off action lies upon the plaintiff, he has to establish the existence of business reputation, distinctive name, and good-will which he seeks to protect. The asset that is protected is the reputation of the plaintiff’s business in the relevant market. It is a complex thing. It is displayed through various indications that lead a customer or a client to associate the business with the plaintiff, i.e., the name of the business, design, the mark, make-up, or color of the plaintiff’s goods, whether real or adopted, the distinctive characteristics of service he supplies or the nature of his special processes. And it is around encroachments upon such indications that passing off actions arise. What is protected is an economic asset.”

The facts of this case are, the plaintiffs Banarasi Dass and Brothers were having registered trademark ‘ELLORA’ and were selling clocks under this trade name since 1955. The defendants started manufacturing clocks with the trademark ‘Gargo’ printed on the dial of the clocks but on the cardboard box containing these clocks were printed with ‘ELLORA INDUSTRIES GARGON (PUNJAB)’. They adopted this as their trading style in 1962. The plaintiffs requested an injunction in order to restrain them from using their mark ‘ELLORA’ or any mark which is similar thereto, for preventing them from letting their goods being represented as the goods of the plaintiffs. As it was a clear case of passing off and also of infringement of the plaintiff’s registered trademark, the plaintiffs were entitled to the injunction.

In the case of Scotch Whiskey Association v. Pravara Sahakar,AIR 1992 Bom 294, 1992 (2) BomCR 219 the plaintiffs used various well-known Scottish figures or Scottish soldiers or Scottish Headgears or Scottish Emblems and market the distilled scotch whiskey all over the world. The act done by the defendants amounted to passing off their whiskey as that of the plaintiffs, as they were manufacturing whiskey in India, using the similar label, figures, carton, devises suggesting Scottish origin of the whiskey, and used the word “Scotch” along with the description “Blended with Scotch.” The court held that the defendants were liable and therefore an order of temporary injunction was passed.

This is another case illustrating the tort of passing off, Kala Niketan, Karol Bagh, New Delhi (Plaintiff) v. Kala Niketan, G-10 (Basement) South Extension Market-1, New Delhi (Defendant), AIR 1983 Delhi 161, ILR 1981 Delhi 592, in this case, the plaintiff was having a business under the name of ‘Kala Niketan’, of selling sarees in Karol Bagh, New Delhi for more than 20 years. They had established a good reputation, name, and goodwill in the market and were having a turnover of several lacs in their business. The plaintiff had spent a huge amount on advertising and then had reached the position which he was having in the market. The defendant started the same trade as well as under the same trade name ‘Kala Niketan’ in the South Extension area, New Delhi.

It was held in this case, that the use of the disputed trade name ‘Kala Niketan’ was established and had achieved the status of a distinctive name for the plaintiff’s business. The use of the plaintiff’s trade name by the defendant was to deceive or most probably cause confusion and injure the business reputation of the same and hence, the plaintiff was entitled to a permanent injunction.

A similar decision was given in the case of M/s. Virendra Dresses v. M/s. Varinder Garments, AIR 1982 Delhi 482, 21 (1982) DLT 472, 1982 RLR 538, the plaintiffs were carrying on the business under the name and style of ‘Virendra Dresses’ of ready-made garments. After two years, the defendants started the same business in the same street under the name and style of ‘Varinder Garments’. The court held that these two trade names were similar, which would create confusion in the minds of people and would mislead therefore the plaintiff was entitled to an interim injunction till the decision of the court was passed.

If the defendant showcases his goods in a similar design with that of the plaintiff although, with a different name, the wrong is still constituted if the public at large is accustomed to purchasing that article with the description of design and get-up rather than by its name. In the case of White Hudson & Co. Ltd. v. Asian Corporation Ltd., the plaintiff’s sold medicated cough sweets in the Singapore market under the name ‘Hacks’, in red cellophane wrappers, various customers of this product could not read English and be into the habit of asking for them as red paper cough sweets. The defendants started the same type of business by selling their cough sweets in red wrappers under a different name ‘Pecto’. The court held that the customers were being misled because of the same package. They were misled in taking the defendants’ product for that of the plaintiffs and the plaintiffs were entitled to an injunction against the defendants.

The important point which is required to be noticed in the tort of passing off is that the action for passing off is only available to the trader for protecting his proprietary right in his goodwill of business and not to the customers of such goods or services who claim of being deceived or confused, or the likelihood thereof, by the use of some particular mark by a trader or manufacturer.

Conclusion

All these torts have a huge importance in the field of tort law as these are the wrongs which interfere in the contractual and business relations and consequently injure the pecuniary interests of the person i.e., business in relation to the actual/potential loss of clients, new business opportunities, existing and new business partners, etc resulting in huge financial loss. These wrongs are tortious as well as criminal in nature and have various aspects related thereto and therefore require many reforms for becoming much more ascertainable.

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skill.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

https://t.me/joinchat/J_0YrBa4IBSHdpuTfQO_sA

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications