This article is written by Anam Khan from Hidayatullah National Law University. The article discusses the detailed study of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy Case. The recent gas leak in the LG Polymers, Vizag compels us to raise an important question, have we learned our lesson from one of the worst industrial accidents- The Bhopal tragedy?

Table of Contents

Introduction

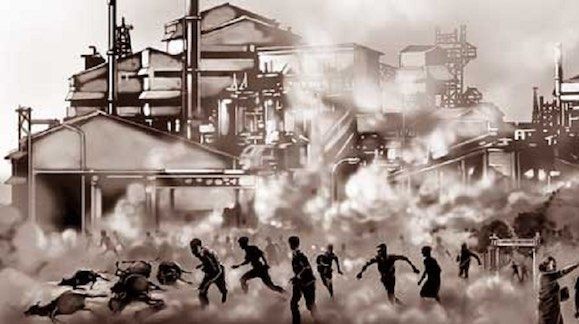

In the early hours on 7th May, a Styrene gas leak in LG Polymers Plant in Vizag claimed 11 lives, leaving 5000 others severely injured. The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has taken this incident into suo moto cognizance. Although the notice by the Commission suggests that there was no negligence or human error, it is still a gross violation of human rights. Later during the same day, a boiler burst at Neyveli Lignite Corporation injured 8 people in Tamil Nadu. Meanwhile, in Chhattisgarh, 7 people fell ill after they accidentally inhaled a toxic gas that leaked from a paper mill factory in the Raigarh district. These incidents of a gas leak remind us of the major accident that happened in Bhopal in 1984; The Bhopal Gas Tragedy. In 1934, Union Carbide India Ltd (UCIL) was incorporated in India to manufacture batteries, chemicals, pesticides, and other industrial products. The American enterprise, Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) owned a majority stake in UCIL. In 1970, UCIL erected a pesticide plant in a densely populated area of Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. At the inception stage, UCC’s Argentine agronomic engineer expressed concerns over the plant’s safety but his superiors disregarded them, saying that the plant would be ‘as inoffensive as a chocolate factory’. With the approval from the Government of India UCIL manufactured the pesticides Sevin and Temik in its Bhopal plant. On the night of 2 December, 1984 water is said to have seeped into a tank containing over forty tonnes of the highly poisonous methyl isocyanate (MIC), a gas that was used in the production of Sevin and Temik. This is said to have caused an exothermic reaction because of which the MIC escaped into the atmosphere- and when the northwesterly winds blew this gas over the hutments adjacent to the plant and also into the very densely populated parts of Bhopal, the city was transformed into a ‘gas chamber’. As many as 2600 people died in the immediate wake of the leak, and the death toll rose to 8000 within a fortnight, while hundreds of thousands were impacted. This is when Bhopal had found a place on the world map for all the wrong reasons.

The ghosts of December 1984 haunted several generations of Bhopal’s inhabitants. Over the next 25 years, although no official death count was undertaken, estimates indicate that the number of fatalities rose to a whopping 20,000 while 6,00,000 people suffered irreparable physical damage. Many who were still in the womb endured its catastrophic consequences. Even today, residents of Bhopal suffer from genetic defects such as damaged reproductive systems, lung problems, and vision impairments due to the gas leak that occurred nearly three decades ago. What followed the accident was as regrettable as the accident itself. The Indian polity, judiciary, legal fraternity, and all the media squandered numerous opportunities to lay down a stern deterrent for those who believed that they could wantonly evade punishment for crimes committed by developing nations. In the years that followed, in their struggle for justice, the victims of the disaster were re-victimized. There was a series of debates and decisions on several issues- ranging from compensation payable to the victims, the criminal negligence of UCIL the piercing of the corporate veil, the criminal liability of the directors of UCIL and UCC, and the appropriate choice of forum- in India as well as the United States of America, but little good trickled down to the victims of this catastrophe.

Parens Patriae and the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster Act, 1985

At the time of the disaster, UCIL’s ownership structure was such that UCC owned 51 percent of the company. Life Insurance Corporation of India/Unit Trust of India owned 22 percent and the Indian public-owned 27 percent. Soon after the leak, hundreds of tort lawyers from the United States of America and their Indian counterparts descended on Bhopal, seeking exemplary damages for those affected by the tragedy. The Government of India was quick to derail their hopes. It promulgated the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster Act, 1985 in March 1985. The Bhopal Act gave the Central Government the exclusive rights to represent and act in place of the persons entitled to make claims in relation to the Bhopal gas leak. It authorized the Central Government to represent the interests of those affected by the gas leak as ‘parens patriae’- this tool, which originated in the United Kingdom and evolved in the United States of America allows the state to protect the well-being of its citizens in a representative capacity.

The Bhopal Act is known to have evoked sharp criticism, as the wrongdoer (UCIL) was partly owned by State corporations and the government could have been held partially liable for the tragedy. By invoking parens patriae, the government began to represent every victim who would have initiated against it. The government’s action has therefore been criticized as the device meant to protect itself from culpability for the Bhopal gas leak rather than protect its victims. The constitutional validity of the Bhopal Act was also challenged before the Supreme Court. Justifying the application of the parens patriae principle, the court held:

The government is within its duty to protect and to control persons under disability. Conceptually, the parens patriae theory is the obligation of the state to protect and take into custody the rights and the privileges of its citizens for discharging its obligations. Our Constitution makes it imperative for the states to secure to all its citizens the rights guaranteed by the Constitution and where the citizens are not in a position to assert and secure their rights, the state must come into the picture and protect and fight for the rights of the citizens. Even though it was tenuous, parens patriae could have been an effective mechanism to obtain a speedy remedy only if the government had pursued it with conviction and while bearing in mind the interest of the victims. However, the government did not match its power with ‘results or responsibility’. The outcome was that the victims were double-crossed by the state- they were left with little compensation and also deprived of their right to act in their individual capacities.

Proceedings before the Keenan Court

Exercising its power under the Bhopal Act, on 8th April 1985, the Central Government filed a complaint against UCC before the Southern District Court in New York, United States of America. By then, 144 proceedings were already underway in federal courts across the United States in respect of the Bhopal gas leak. All these proceedings were consolidated and assigned to the court of Judge John Keenan. The arguments projected a strange situation- the Union of India argued that Indian courts could not handle the matter efficiently while a United States corporation asserted that they could. India ‘biopsied’ it’s own legal system while an American corporation celebrated it! Acting on behalf of the victims, the Indian government started the following-

- India’s legal system was ill-equipped to handle the complex litigation that the case would entail.

- The endemic delays in India’s legal system and the substantial backlog of cases would impede the effective disposal of the case.

- Indian lawyers could not provide proper representation due to a lack of expertise in the area of tort claims.

- Tort law in India was not developed enough to deal with a case of such gigantic proportions.

- Procedural law in India would hinder the path of justice for the victims.

The court extensively discussed whether the Indian courts were competent enough to grapple with the Bhopal disaster case. Judge Keenan concluded that the arguments were untenable and dismissed the claims on the ground of ‘forum non-conveniens’- a doctrine based on which the court can refuse jurisdiction over a case where a more appropriate forum is available. The court held that most of the documentary evidence concerning the design of the plant, safety, and setup was in India, as were the vast majority of witnesses who could be examined. Moreover, the Indian government had an ‘extensive and deep interest’ in assuring compliance with safety standards. Judge Keenan believed that India’s interest in developing minimum standards of care was superior to the United State’s interest in deterring multinationals from exporting dangerous technology to other nations. Strikingly, Judge Keenan made certain politically flavored observations on the potential of Indian courts to dispense justice:

To retain the litigation in this forum would be yet another example of imperialism, another situation in which an established sovereign inflicted its rules, its standards, and values on a developing nation. This court declines to play such a role. The Union of India was a world power in 1986, and its courts have the proven capacity to mete out fair and equal justice. To deprive the Indian judiciary of this opportunity to stand tall before the world and to pass the judgment on behalf of its own people would be to revive a history of subservience and subjugation from which India has emerged. India and its people can and must vindicate their claims before the independent and legitimate judiciary created there since the Independence of 1947.

The dismissal of the Union of India’s case was subject to three conditions:

- UCC would have to consent to submit to the jurisdiction of Indian courts and continue to waive defenses founded on the statute of limitations.

- UCC would have to abide by any judgment rendered by an Indian court as long as it complied with ‘minimal’ due process requirements.

- After an appropriate demand by the Union of India, UCC was to be subject to discovery under the model of the United State’s Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Judge Keenan’s decision was ironic- the great opportunity that he believed India’s legal system faced was squandered by the bar and the bench.

Back in India, the Meagre Settlement

So, in September 1986, the Union of India instituted proceedings against UCC in a district court in Bhopal, which ordered UCC to deposit an interim compensation of 350 crore rupees. On appeal, the Madhya Pradesh High Court reduced the figure to 250 crore rupees. UCC appealed to the Supreme Court of Indian law, a judgment debtor is supposed to deposit the contested amount before moving an appellate court, UCC did not do so.

Aiming to dispense speedy justice to the victims, the court ordered UCC to pay 470 million dollars crore ‘in full settlement of all claims, rights, and liabilities related to and arising out of the Bhopal gas disaster’. The compensation amount was a mean between UCC’s offer of 426 million dollars and the Union of India’s demand for 500 million dollars. In terms of the settlement, all civil proceedings were concluded and criminal proceedings quashed in relation to the Bhopal gas leak. Although the five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court passed this order on Valentine’s Day 1989, the victims had no great affection for the order, since the Central government had earlier kindled their hopes of obtaining compensation amounting to 3 billion dollars- more than six times the final settlement amount.

A few months later, the Supreme Court issued a reasoned decision for its order granting compensation to the victims. One of the unfortunate effects of the settlement was that the court did not adjudicate on critical issues raised by the Bhopal incident, though it stated its observations on the need to protect national interests from being exploited by a foreign corporation and develop criteria to deal with potentially hazardous technology. The Supreme Court reiterated that the compensation was adequate and that it actually exceeded personal injury claims that time. It clearly failed to appreciate the extent of the damage caused by the Bhopal gas tragedy and its crippling long term effect. It would not be wrong to say that Indian laws do not value lives as much as it is valued by other nations. Is it because we have so many people that not each and everyone matters?

Criminal Charges Revived

The settlement sanctioned by the Supreme Court was widely condemned. A few years after the 1989 settlement order, the Supreme Court clubbed several petitions filed against the order and formed a five-judge Constitution Bench to hear arguments challenging the basis of the settlement. In exceptional cases, the Supreme Court has the power to review its own judgment, under Article 137 of the Constitution. However, before the judgment could be pronounced the then Chief Justice of India, Justice Sabyasachi Mukherjee, passed away. This necessitated a rehearing which caused further delay. In its judgment dated 3rd October 1991, the Court finally recognized the legal sanctity of the order recording the settlement between UCC and the Union of India. It wasted the opportunity of revising the 470-million-dollar compensation to a more realistic figure. The court also emphasized the need to grant speedy justice to the victims- by its own calculations, the full adjudication of the suits relating to the Bhopal disaster would have taken till 2010.

Nevertheless, the judgment did have two positive consequences. First, it clearly catalyzed the condemnation of the quashing of the criminal process against the UCC officers and the revival of the criminal proceedings against them. Second, the court held that if the settlement amount fell short, the Union of India was bound to make good the shortfall. Remarkably, Justice Aziz Mushabber Ahmadi, who went on to become the Chief Justice of India in 1994, dissented on this point, questioning why the Indian taxpayer should be liable when the Union of India was neither held liable in tort for the disaster nor was shown to have acted negligently while entering into the settlement.

Criminal Proceedings Against UCC and UCIL Officers

After the criminal proceedings against the directors and officers of UCC and UCIL recommenced, many criminal cases did the rounds in courts across India. Initially, charges framed against the accused under Section 304 of the Indian Penal Code for culpable homicide not amounting to murder- an offence punishable by imprisonment for a maximum of ten years. Responding to an appeal, the Supreme Court diluted the charge to ‘causing death by negligence’ under Section 304A of the IPC on the ground that the evidence was not sufficient to charge the accused with culpable homicide. The trial proceeded in the Chief Judicial Magistrate’s Court, and on June 7, 2010, seven people were convicted for two years each in connection with the Bhopal gas leak. Warren Anderson, the Chairman of UCC at the time of the leak did not appear in court and was declared an absconder. Though the court slapped the maximum punishment it could, it was sharply criticized for treating the disaster like a ‘minor traffic accident.’

Give to the Rich and Rob from the Poor?

The Bhopal gas leak was cited by many as the paradigm of how influential multinationals exploit developing countries; developing countries import hazardous technology in spite of a conspicuous absence of an environmental law framework and legal infrastructure to handle its potentially disastrous consequences. The most ironic aspect of globalization in the 1980 and 1990s was that in their quest for economic development, developing countries sacrificed the human rights of the lowest rungs in their societies. Foreign companies were accused of committing some of the most heinous crimes- from homicide and rape to forced labour. Bhopal was undoubtedly the darkest reflection of globalization against its benefits, particularly when modern technology was imported into an archaic legal set-up, as was the case with India.

Bhopal and BP

In 2010 an oil spill of unprecedented magnitude happened in the Gulf of Mexico when a mobile offshore drilling unit, which was drilling an exploratory well, exploded and leaked out close to 5 million barrels of crude oil. Within weeks of the incident, BP- the corporation that was held responsible for the spill- created a 20 billion dollar fund to deal with the accident. Within two years and four days of the incident, federal investigators in the United States of America made their first arrest in the matter. The incidents in the Gulf of Mexico and Bhopal are acutely distinct: the former wreaked massive environmental destruction, while the latter decimated thousands of humans and deprived thousands more of the basic quality of life. The former also took place at a time when environmental law was more equipped to handle mass disasters. At the same time, one cannot help but notice the differential treatment of the two incidents. Had the accident occurred in Indian waters, would BP have paid even half of the compensation it eventually did?

Have We Learned Our Lesson from Bhopal?

The Bhopal gas disaster jolted lackadaisical politicians and policymakers. Before 1984, India only had specific legislation pertinent to air and water pollution. After the Bhopal gas tragedy, India enacted the Environment Protection Act, 1986 a statue that seeks to address pressing concerns involving sustainable development. This was followed up by the enactment of the Public Liability Insurance Act, 1991, and the National Environment Tribunal Act, 1995. However, despite all the environmental legislation, there is still a definite lacuna in the Indian legal structure. On 6 July 2011, the UN General Assembly adopted the ‘Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework’ a report by Harvard Law School professor and United Nations Special Representative John Ruggie. As per the UN Framework, governments must clearly spell out their policies to protect human rights and communicate these to business organizations. Further business must undertake a regular human rights impact assessment (HRIA) and due diligence, and create internal policies to ensure compliance with human rights norms. So, despite the government’s steps in the aftermath of Bhopal, there is still room for a substantial number of measures to be undertaken. The recent Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Bill, 2010 caps the liability of nuclear plant operators for nuclear accidents to 1500 crore. This amount is lower than the 470-million-dollar compensation awarded in the Bhopal case, which in itself was grossly insufficient. The proposed framework of nuclear liability law has created a dangerous cocktail for another Bhopal. It reinforces the fact that justice in India is still administered reactively, not proactively.

Conclusion

The recent Vizag gas leak is said to have been reminiscent of the Bhopal accident. It is a stark example of how casually certain industries treat environmental guidelines. Production plants such as these are rarely shut, let alone switched off abruptly, the scientist said. The lockdown, however, forced all industries, except those making essentials, to shut down. It is not known whether there was sufficient staff, monitoring key storage parameters, and sensors. In its eagerness to catch up with its richer neighbour, India should not repeat its mistakes. There is indeed a case for reforming some of the archaic and rigid labour laws that have unintended consequences. But a correction should not mean the pendulum swinging in the other direction.

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) under the Union Home Ministry has said that the manufacturing units which will restart after the Covid-19 lockdown ends, should consider the first week as the trial period. “Due to several weeks of lockdown and the closure of industrial units during the lockdown period, it is possible that some of the operators might not have followed the established SOP. As a result, some of the manufacturing facilities, pipelines, valves, etc. may have residual chemicals, which may pose risk,” the NDMA said in a letter to the states. In a nutshell, the Achilles’ heel of Indian policy is exposed.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications