Sexual harassment is a malady which has a large array of corrosive effects on business and workplaces – it undermines the rights and liberties of women and creates a hostile work environment. It can lead to a PR disaster for an employer (think Tehelka) and destroy the career of an accused. It can drastically reduce employee morale and affect productivity and loyalty of employees. Sexual predators may take advantage of organization’s culture and structure to engage in sexual harassment and create hostile work environment that damages a business’s reputation, profitability and internal workings. Read about psychology of sexual harassment: http://blog.ipleaders.in/the-psychology-of-sexual-harassment/

To understand sexual harassment in its entirety, it is necessary to view sexual harassment at the workplace from a historical perspective and look closely at the reasons which prompted the legislature to enact a law to combat this menace.

For centuries, sexual harassment has been a persistent and pervasive practice in most workplaces. Even in popular culture, depictions of sexual encounters and innuendos in the workplace has been pervasive and we can paint a pretty good picture of what it meant to be a woman in the workplace dominated by men from advertisements and movie scenes.

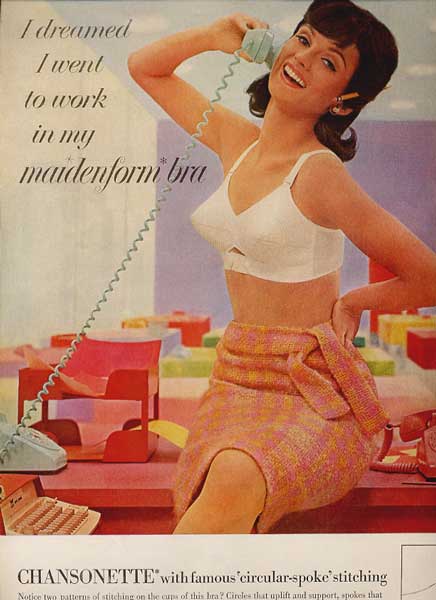

See this ad for example, from 1942:

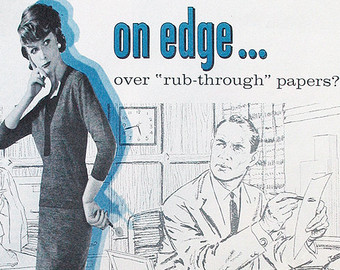

From 1961:

Marilyn Monroe as secretary:

Or this indie film poster from 2002:

Think of all the James Bond movies that propagate the idea that women at workplace are hungry for manly attention and probably sex.

As Reva B. Siegel rightly points out in this article, both slaves and domestic servants in the antebellum period in America were repeatedly subjected to sexual assault. Moreover, they were blamed for their own downfall as they were considered to be promiscuous by nature.

As Naina Kapur rightly observes in this article, in the 1980s, most women repeatedly emerged from the criminal justice system more humiliated, less empowered and with almost no sense of self left intact. This is epitomized by the gang rape of a tribal girl within the precincts of a police station in 1983, known as the Mathura case.

At the time of the incident, the girl’s boyfriend and family members were standing outside the police station. In its judgment, the Supreme Court of India described the girl as a “vicious liar” and stated that she was “habituated to sexual intercourse”. It further stated that the failure of the girl to ‘resist’ implied consent to the abuse.

In the 1980s, militant action by the Forum Against Oppression of Women (Mumbai) against the sexual harassment of nurses in public and private hospitals by patients and their male relatives, ward-boys and other hospital staff; of air-hostesses by their colleagues and passengers; of teachers by their colleagues, principals and management representatives; of PhD students by their guides, etc received a lukewarm response from the trade unions and adverse publicity in the media (FAOW, 1991). Despite the sorry state of affairs, many women came forward to report cases of sexual harassment at the workplace.

In Goa, Baailancho Saad (‘Women’s Voice’) forced the chief minister, who allegedly harassed his secretary, to resign by organising demonstrations and protest rallies.

Before 1997, victims of sexual harassment were completely at the mercy of police officers who often refused to register such complaints. It is dismaying to note that there was no mechanism to hold such police officers accountable. Until 1997, women could lodge a complaint for sexual harassment at the workplace under 2 main provisions of the Indian Penal Code, 1860: under S. 354 which pertains to the criminal assault on a woman to outrage her modesty, and S. 509 which pertains to the use of any word/gesture/act to insult the modesty of a woman.

The brutal gang rape of a Rajasthan state government employee brought the issue of sexual harassment at the workplace to the forefront of national public debate. The woman, who was a worker of the Women Development Programme, tried to prevent the occurrence of child marriage. The men who repeatedly raped her described her as “a lowly woman from a poor and potter community”. In the legal battle that subsequently ensued, the Rajasthan High Court did not hold the rapists responsible and the survivor did not get justice. Vishakha, a women’s rights group, vehemently opposed this decision and filed a public interest litigation in the Supreme Court of India. In its landmark decision in the case of Vishakha vs State of Rajasthan [1997(7) SCC.323] the Supreme Court recognized the absence of domestic law occupying the field and the need to formulate effective measures to check the evil of sexual harassment of working women at all work places. As a result, the SC issued a comprehensive list of guidelines about how employers should deal with cases of sexual harassment at the workplace. It also stated that these guidelines would only be applicable until the enactment of a law by the legislature to curb this menace.

Almost 10 years later, in 2007, the then women and child development minister, Krishna Tirath, introduced a bill known as the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Bill.

It is dismaying to note that this bill was approved by the Union Cabinet only in January 2010. It was tabled in the Lok Sabha in December 2010 and referred to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Human Resources Development. The committee’s report was published on 30 November 2011. It was finally approved by the Lok Sabha in September 2012 and the Rajya Sabha in February 2013. The aforementioned data clearly shows the lackadaisical approach of the legislature while dealing with such a crucial issue of national importance. This delay can also be attributed somewhat to the failure of NGOs working for the rights of women in effectively asserting the rights of working women and lack of attention from the mainstream media and political parties.

Even after the law has been passed, it is an uphill battle – as most of India’s employers are far from implementing the law that has been made. Government has not taken any step yet to ensure that employers implement the law. The law, however, imposes an INR 50000 fine for non-compliance on employers. There are little resources and few experts available even for those employers who are willing to allocate resources towards implementation of the anti-sexual harassment law.

What could you do to make a difference?

If you are an employee (irrespective of your gender) in any Indian workplace, please visit http://endsexualharassment.ipleaders.in/ to learn about your rights and duties for free. You can also report violation or non-compliance by an employer (yours or any other) over here: http://endsexualharassment.ipleaders.in/report we would contact your employer and ask them to implement the law, and assist in the process. We keep all our sources strictly anonymous. You can also take a pledge here to End Sexual Harassment and spread awareness about the cause.

If you are an employer, compliance professional or an HR professional in need of a simple solution to implement this law, please visit this page: http://endsexualharassment.ipleaders.in/employers-toolbox

You can know more about the law and various compliances related to it by taking up this course which is created by National University of Juridical Sciences. You can also learn about implementation of sexual harassment laws by taking up this course.

This article was jointly written by Ramanuj Mukherjee, co-founder of mass legal education startup iPleaders and Rahul Bajaj, a visually challenged law student at Nagpur University who is interning at iPleaders.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications