This article has been written by Manjri Singh, student of NALSAR University, Hyderabad.

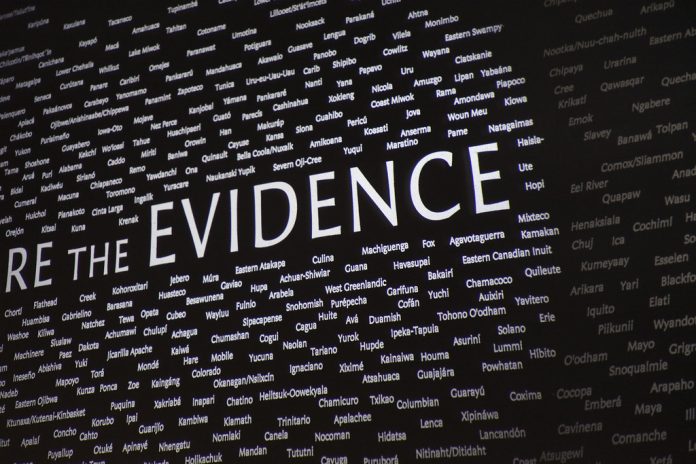

The recent judgment by the Supreme Court in the review petition by Yashwant Sinha, Arun Shourie and Prashant Bhushan dismissed the preliminary objection by the Respondents of maintainability given the submission of certain illegally procured evidence.[1] In this analysis, the judgment is scrutinized not just in relation to the admission of illegal evidence but also what are the notions or rationale of justice that guides evidence. Evidence arguably affords the judiciary the widest ambit of its discretion although it is significantly curtailed by the Indian Evidence Act. A colonial legislation operating on colonial logic and objectives has not been amended as such and it is important to note that even in the definition of proved given in the Act states that a fact is proved if the Court believes it to be true (or a prudent man would believe it to be true).[2] Such a provision is not as problematic when the evidence presented, admitted and relied on are on public record or reasoned in the judgment available to the public. This provision becomes a lot more problematic when the evidences sought to be relied upon are not available to the public and sometimes even (sufficiently) to the other party in the suit. In this context, it is interesting to note what attitude the highest court of judiciary adopts with respect to possibly illegal evidence, how it was obtained and what constitutes the public arena. This case is based on a high-profile political controversy around the 36 Rafale jets deal signed between India and Dassault. Intertwined in this controversy, are Inter governmental agreements on confidentiality of evidence, claims of national security and sensitivity towards commercial interests as concerns of making public details of the agreement and scores of allegations as to abuse of confidentiality and corruption.

In this matter, an earlier three judge bench comprising of the Chief Justice of India, Mr. Ranjan Gogoi, Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul and Justice K.M. Joseph had adjudicated upon multiple Public Interest Litigations that dealt with deal of the Indian government with Dassault for the procurement of 36 Rafale fighter jets that replaced the tender of the United Progressive Alliance for 126 Medium Multi Role Combat Aircrafts, for which again Dassault was accepted as the lowest bidder.

With respect to evidence, it was ordered that whichever of the sealed documents provided to the Court could be released in the public domain be sent to the Petitioners.[3] The Apex Court also considered the sealed documents provided to it and remarked affirmatively on the need for privacy in some matters and noted that the pricing details and other documents had not been made available even to the Parliament owing to their sensitivity in national security matters. In the same, the Supreme Court had decided on the basis of the sealed documents provided by the Government, that the decision-making process, difference in pricing and the Indian Offset Partner contained no illegality, procedural impropriety and could not be interfered with on any count.

The revision petition is to be decided by the same bench and on the same facts with three additional documents filed by the Petitioner. The judgment deals with the preliminary objection by the Respondents as to the maintainability of the petition owing to the documents being unauthorizedly removed from the office of the Ministry of Defence, Government of India. The Respondents prayed for the removal of these documents from the record relying on provisions of the Official Secrets Act, Right to Information Act and Section 123 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. The Court noted that the documents in question had been published by ‘The Hindu’ newspaper on two dates in the month of February, 2019. This judgment delivered on April 10, 2019 held that the petition would be maintainable and set aside the objection of the Respondent.

The Respondents in this case relied on Section 123 of the Indian Evidence Act amongst other Acts. Section 123 of the Act is as follows:

“Evidence as to affairs of State—No one shall be permitted to give any evidence derived from unpublished official records relating to any affairs of State, except with the permission of the officer at the head of the department concerned, who shall give or withhold such permission as he thinks fit.”

The section deals with the privilege of unpublished official records relating to the affairs of the State being produced. This section is in the nature of an exception to the general rule of admissibility under the Evidence Act[4]. Given the law, in the instant case, the judgment turned primarily on the fact that the documents in question had already been published by a newspaper. Therefore, as the documents were already in the public domain, (a fact accepted by the Respondents which did not even contest the authenticity and accuracy of such documents), there was no reason as to why they should be struck off the record in the case (which was the relief prayed for by the Respondents). At the point, it is noted that there were two separate issues that were dealt with as one by the Hon’ble Court. These are confidentiality and illegality of obtaining the evidence with reference to Section 123 respectively. The Court however, only considered the first, that is confidentiality and went on to re-emphasis the freedom of the press and ultimately also held that the Right to Information Act overrides any contrary provisions in the Official Secrets Act. The researcher believes that this has the following profound impacts on admissibility of evidence. First, it has been held by Courts that illegally obtained evidence is never a factor in consideration of its relevance.[5] However, this case must be distinguished given that it involved concerns of national security and confidential documents. An important factor here is that the documents published in the newspaper was not verified or certified, consequently even if the press was excluded from the purview of Official Secrets Act and Section 123 of the Evidence Act, in using such documents, the originals may have to be ordered to be produced or other classified documents might be ordered thereby intersecting again with the defence of Section 123. A second consideration is that the Apex Court in this case did not deal with the Respondents query as to the method in which the Petitioners had obtained the documents (not from the newspapers?). A stress on confidentiality (which no longer existed) over illegality of obtaining documents as adopted in the Court’s approach could possibly create a loop hole where in confidential documents would be leaked and subsequently used as evidence in Court, keeping in mind the context of national security concerns. This possible loop hole could be avoided using the Court’s verdict on the primacy of the Right to Information Act (RTI) from the judgment itself where Justice K.M. Joseph states that requests under Right to Information Act would be obliged to over the Official Secrets Act should a case be so made, and the copies of documents so obtained would be certified. These certified copies obtained without the Official Secrets Act restriction forms a better method of presenting the same evidence keeping in line with the best evidence principle. This would also sufficiently address concerns of illegally obtained evidence of such nature being published in the media and then being used as evidence which would require further corrobation, a possibility which seeks to threaten the entire rationale of Section 123. It also addresses the problem of partial documents of a series being available and used and thereby creating bias, as the whole series of documents can be availed under the RTI Act. The final question also lies in the evidentiary value of an unverified, uncertified document, the accuracy of which cannot proved by the Petitioning party (a scenario that wasn’t considered due to the manner of objection raised). This solution could have been realised by a simple interpretation that unverified and uncertified documents in the media would not constitute “published” for the purposes of Section 123, as distinguished in an Australian judgment that Justice K.M. Joseph himself quoted[6].

In the last comment, it is mentioned that the Supreme Court in this case although highlighting very relevant principles and judgments that would strengthen democratic processes and values could have rendered a more effective opinion with respect to evidence and its procurement had the difference between mere confidentiality and illegality of method been considered. The researcher has also aimed at providing an alternate interpretation of the Section that accordingly takes all concerns into account.

Endnotes

[1] Yashwant Singh v. Central Bureau of Investigation, AIR 2019 SC 1802.

[2] §3, Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

[3] supra note 1, at Paragraph 14.

[4] State of J&K v. Anwar Ahmed Aftab, AIR 1965 J&K 75.

[5] Pooran Mal v. Director of Evidence, AIR 1974 SC 348.

[6] supra note 1 at para 39 and 40.

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skill.

https://t.me/joinchat/J_0YrBa4IBSHdpuTfQO_sA

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications