This article is written by Sri Vaishnavi, and further updated by Debapriya Biswas. The article deals with the analysis of the landmark case of A.D.M. Jabalpur vs. Shivkant Shukla (1976). It discusses the issues raised in the case and the principles established by the Supreme Court to address these issues. Lastly, the article traces the significance of the judgement as well as the future implications it may have brought even in the present times. The case primarily dealt with the balance between the interests of the State and the rights of the citizens of the country, particularly during the proclamation of an emergency.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The fundamental rights enshrined in Part III of the Constitution of India, are a part of the basic structure of the Constitution. It not only establishes the rights of the citizens but also stands as a protector of the universal rights that are derived from natural law. Without these rights, the overall development of an individual could be compromised, leading to poor quality of life and even deprivation of the full potential they could achieve. Thus, every nation has codified the basic human rights or the ‘fundamental’ rights to prevent the same from happening.

However, in some circumstances, fundamental rights can be restricted or even suspended for a limited period, such as in the case of national or state emergencies. During the emergency period, certain fundamental rights are suspended in the interest of the State and its security. However, the question that arises here is regarding the extent to which the State should be prioritised and whether it would be constitutional to suspend even the crucial fundamental rights, such as the right to life and personal liberty during such dire times.

In the present article, we will explore the answer, with a detailed case analysis of A.D.M., Jabalpur vs. Shivkant Shukla (1976), wherein the same question was raised.

Brief details of the case

Name of the case

Additional District Magistrate, Jabalpur vs. Shivkant Shukla

Parties in the case

Petitioner: Additional District Magistrate, Jabalpur

Respondent: Shivkant Shukla

Court

The Supreme Court of India

Judges/Coram

- Hon’ble Chief Justice of India A.N. Ray;

- Hon’ble Justice Hans Raj Khanna;

- Hon’ble Justice M. Hameedullah Beg;

- Hon’ble Justice Y.V. Chandrachud;

- Hon’ble Justice P.N. Bhagwati.

Date of judgement

April 28th, 1976

Citation

AIR 1976 SC 1207, 1976 SCR 172, 1976 SCC (2) 521.

Background of the case

Till date, national emergency has only been proclaimed three times in India. The first one was declared by the then Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, in October 1962, due to Chinese hostility leading to external aggressions. It lasted till 1968 and was only lifted after public dissatisfaction. The second national emergency was proclaimed on December 3rd, 1971 due to external aggressions from Pakistan. To deal with the emergency more effectively and efficiently, the Maintenance of Internal Security Act, 1971 (hereafter referred to as the MISA) was introduced.

It wasn’t until November 16, 1974, that the President of India declared through an ordinance, that the right to approach the judiciary with regard to detentions made under Section 3(1) (power to make orders detaining certain persons) of the MISA, and for the enforcement of rights under Article 14 (right to equality), Article 21 (right to life and personal liberty) as well as Article 22 (prevention against detention in certain cases), would be suspended for six months from the issue of the order or till the emergency period ends, whichever is earlier. This also included the suspension of all the proceedings pending in the court relating to the same. This was the first order that started the suspension of rights during a national emergency, although it was for a limited period of six months at the time.

It was later amended on June 20, 1975, to increase the period from six months to twelve months, before being completely suspended for the whole duration of the emergency in an order dated June 27, 1975. These orders were proclaimed by the President in the exercise of the powers conferred by Article 359(1) (suspension of the enforcement of rights conferred by Part III during emergencies) of the Indian Constitution.

However, the key issue with these orders was not only the restrictions of the rights themselves but also their time limit. The initial six months extending up to a year and then till the end of the emergency, which can take more than a few years, was quite arbitrary and prone to misuse. The present case is the very proof of the same when the third national emergency was proclaimed in India.

Historical Background

The history behind the current case starts with the judgement of another case, namely, State of Uttar Pradesh vs. Raj Narain & Ors (1975), in which the then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, was held guilty of unlawful practices relating to elections in Lok Sabha. The respondent of the aforesaid case, Raj Narain, had initially filed a petition before the Allahabad High Court in which he alleged that Indira Gandhi had committed malpractices like financial misuse of public funds to get re-elected as the Prime Minister. The government had, interestingly enough, failed to submit any affidavit against the allegation made. This made the High Court of Allahabad hold the judgement in favour of Raj Narain, aggrieved by which, the State appealed it to the Supreme Court of India.

The Supreme Court also held the judgement in favour of the respondent, Raj Narain and put a conditional stay to the previous verdict. The Court further declared the previous election as void and convicted Indira Gandhi for her malpractices, by restricting her right to participate in the elections or even represent herself as a member of the Lok Sabha for the next six years.

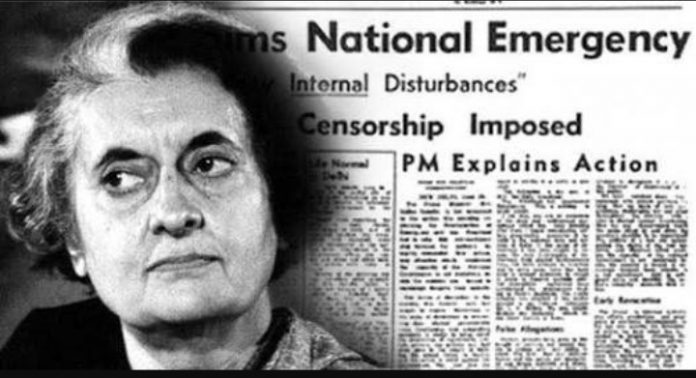

However, before another election could be conducted or Indira Gandhi’s reign could be set aside, she requested to declare a national emergency under Article 352 (proclamation of emergency) of the Indian Constitution, which the then President, Fakruddin Ali, proclaimed on June 25, 1975 by an ordinance. This proclamation of emergency was made through a late-night nationwide broadcast on All India Radio.

This was the third and last national emergency ever declared in India to date, with the reason for such an emergency being that ‘internal disturbances’ were threatening the government. By doing this, Indira Gandhi was able to prolong her reign by delaying the enforcement of the judgement in the State of Uttar Pradesh vs. Raj Narain (1975), despite being asked by the Allahabad High Court to refrain from parliamentary proceedings.

Although it can be argued that India was indeed amidst turmoil at the time, given how there was a statewide strike in Gujarat known as the ‘Navnirman Andolan’, which was organised on January 25, 1974. It resulted in a short curfew being placed on at least 44 towns of Gujarat before the army was summoned to restore public order. In addition to that, another movement was happening in Bihar at the same time, which was led by the popular socialist Jayaprakash Narayan along with many other Indian students against the corruption of the state government. The year 1974 also saw the largest industrial strike in history by the 17 crore workers of the Indian Railways, which lasted up to 20 days.

Be that as it may, it cannot be argued that most of these movements of unrest happened long before the emergency was declared and were resolved subsequently as well. Thus, these movements cannot be held as the ‘internal disturbances’ cited by the President.

On June 27, 1975, the President enforced Article 359(1) of the Indian Constitution, as per which, the right to approach the court under Article 14, Article 21 and Article 22 was suspended for the period of the national emergency, for all the Indian citizens and foreigners. All the ongoing proceedings relating to the enforcement of the aforesaid Articles were also suspended. The aforesaid presidential order also stated that the same would be applicable to any and all orders made before the current order. On June 29, 1975, the President made the previous ordinance applicable in Jammu and Kashmir as well, through another presidential order.

The aforesaid presidential orders and ordinance resulted in the arrest and detention of anyone who was deemed to cause ‘internal disturbances’ through riots or any other political threats to the present government. All such detentions were made as a preventive measure under the MISA, the sufferers of which were mostly leaders from opposition parties, who were more of a threat to Indira Gandhi and her political position, than the country and its internal system.

In addition to this, many further amendments to the Constitution, as well as other statutory laws were introduced during the emergency, in favour of the present government, which were also opposed by the public and the aforesaid opposition leaders. A more detailed evaluation of the facts of the same would be covered further in the article.

Social background

The 1970s was a very crucial period for India, especially with the recent conflicts with its neighbouring countries still brewing after proclaiming its independence from the Britishers quite recently. At that time, the interests of the State were prioritised in a manner that maintained the much needed stability and security of the nation. Even a hint of unrest could result in chaos amongst the public and threaten the sovereignty of the State and the government, while also jeopardising the safety of its citizens.

Unfortunately, this also meant that with the priority given to the State, the interests of the individuals were overshadowed, if not compromised, in the name of the ‘greater good’ of the nation. India was still establishing its position as an independent nation after being ruled by others for centuries — a fact known by all and also used to justify the need for the State to be given more power to ensure security and safety.

However, unrestricted power gives way to arbitrariness and that can result in cases of violation of fundamental rights of the citizens. This was best observed during the emergency period when the restriction on individual rights was stricter, but all the power and its enactment was made in favour of the State.

The present case of A.D.M. Jabalpur vs. Shivkant Shukla was a prime example of the same. A nationwide emergency was declared, citing ‘internal disturbances’, with no real threat to be proven. The whole proclamation of emergency was used as a measure for the then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, to maintain her position for a longer period and prolong her reign, to avoid being removed.

With the emergency provisions misused in this manner, they were further used as an excuse to cover the gross violation of fundamental rights of the citizens, especially those who were deemed a ‘threat’ to the State due to their political opinions. They were detained indefinitely and without any sufficient grounds that were not even communicated to them or their family. These detentions were made as a ‘prevention’ and, thus, had no proper trial. The complete control over the citizens without any check or balance from any other organ of the government, led to quite a few constitutional actions, including overreaching amendments and human rights violations.

While it is true that internal disturbances are also a valid reason for the proclamation of national emergency, it is to be assumed that such should only be done in case of extreme situations, such as civil war and widespread rebellion across the nation. Even then, restrictions on fundamental rights under Articles 14, 21 and 22 are very extreme and can be misused in the most inhumane manner, especially the suspension of the right to life and personal liberty. A democratic nation completely suspending all fundamental rights of its citizens sounds quite contradictory for a country whose government is made for the people, by the people, of the people.

A national emergency in itself is an extreme measure that was designed to be opted only in extreme circumstances. Even if not the case, the suspension of certain fundamental rights could lead to an arbitrary State with no opposition. In the present case, since Articles 21 and 22 were suspended till the end of the emergency period, anyone saying anything against the government was detained without a proper trial or procedure.

These unlawful detentions made for indefinite periods not only violated the basic human rights of the citizens but also opened the path for custodial violence. It infringed the freedom of expression and even the right to be heard by a legal representative since none of the detainees were brought in front of a proper judicial authority after their preventive detention. In a democratic nation like India, losses like this can be very critical if left unchecked and not addressed appropriately.

Unfortunately, at the time of the third emergency, India was still learning and so was the public. Legal, as well as political awareness, was very limited among the people of India. In addition, the political influence of the government was much stronger than before and could result in biased opinions and judgements, as we would further read in the article.

It wasn’t until the emergency was lifted and the political scenario of India changed that genuine opinions were shared regarding the proclamation of emergency and the oppression of the public during the said emergency period, as seen in the present case and its aftermath.

Legal background

According to Dr B.R. Ambedkar, the Indian federal system should use the provision of emergency as a last resort and the government should change itself to a unitary system from a democratic one to safeguard the Constitution and the nation itself. With all the power centralised in the hands of the State, it can become better equipped to deal with the internal or external aggression due to which the emergency was declared in the first place.

This power of the government is derived from the constitution itself. There are three types of emergencies under Part XVIII of the Indian Constitution:

- National emergency

- Failure of constitutional machinery in states

- Financial emergency

Article 352 of the Constitution talks about a national emergency, which can be declared in case of war, external aggression or rebellion. During this period, the central government takes all the powers in its hands, namely, the executive, legislative and financial powers of the State.

During the period of a national emergency, except Articles 20 and 21 of the Indian Constitution, all other fundamental rights are suspended. The President can also suspend the right to approach courts by enforcing Article 359. Furthermore, the union government can make legislation on state list items by way of Article 250.

Article 356 of the Indian Constitution talks about the second type of emergency, which is the state emergency in case of failure of constitutional machinery. In simpler terms, if a state fails to follow provisions enshrined in the Indian Constitution or goes through a severe incident, (such as armed conflicts, riots or civil unrest), then the President can declare a state emergency based on their own observations or on the formal request of the Governor of the said state.

State emergencies can also be declared if a state is under biosecurity or at risk of going through an epidemic that may spread all across the nation if not immediately isolated. Natural disasters can also result in the proclamation of a state emergency, depending on its severity and the needs of the state. In addition, Article 365 of the Indian Constitution also talks about state emergency in case the state fails to comply with or enforce any direction given by the union government.

State emergency under Article 356 of the Constitution, which is also known as the ‘President’s rule’, has been declared more than 125 times across India, in the past few decades. In fact, more than a fifth of these instances were recorded under the regime of Indira Gandhi from 1966 to 1977, specifically in the states where the political party Congress was not in power. This clearly showcases how extensively such provisions can be misused if no proper limitations are placed.

Lastly, Article 360 of the Indian Constitution talks about the third type of emergency, that is, financial emergencies. As per this constitutional provision, if the State is going through economic instability and insufficient credibility, the President can declare a financial emergency. This is to be done when there is no other means to address the issue, other than proclaiming emergency. To this day, no financial emergency has been declared in India.

Later on, further changes were brought into the emergency provisions through the 44th Amendment of the Indian Constitution, which we will be covering in detail later on in this article.

Facts of A.D.M. Jabalpur vs. Shivkant Shukla (1976)

As covered earlier in the article, the third Indian national emergency was declared on June 25, 1975, due to internal disturbances that were threatening the stability of the government and the nation itself. However, it is widely believed that the proclamation of emergency was more to prolong the reign of the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi than internal disturbances claimed.

After the declaration of emergency, another presidential order was enforced on June 27, 1975, which suspended the right to approach the Court for petitions relating to Articles 14, 21 and 22 under Article 359(1) of the Indian Constitution. This order was applicable to both foreigners and Indian nationals. Furthermore, it also suspended the ongoing judicial proceedings relating to the above mentioned Articles. Another order on June 29, 1975 made the same applicable in Jammu and Kashmir as well.

After this, certain amendments were introduced in several statutory laws, as well as in presidential orders, from the period of June 25, 1975, to January 26, 1976. These amendments were as follows.

The President promulgated amendment orders nos. 1 and 7 of 1975 and replaced them with the MISA (Amendment) Act, 1975, which introduced a new Section 16A (special provisions for dealing with emergency) and gave effect to Section 7 (powers in relation to absconding persons) of the said legislation, with some changes. The law was enforced from June 25, 1975, and the other provisions came into effect on June 29, 1975. By the same Act, a new Section 18 (exclusion of common law or natural law rights, if any) was also inserted, with effect from June 25, 1975.

On October 17, 1975, another presidential ordinance was passed, as order 16 of 1975, which introduced new amendments to Section 16A of the MISA, by adding Sub-sections (8) and (9). Sub-section (8) of Section 16A specifies that the state government has the obligation to report and notify the central government of any detentions made, as well as modifications and revocations that are to be made to the orders of detention. Sub-section (9) states that the grounds for detention or declaration of detention order, modification or revocation of detention orders, and confirmation or review of the detention, shall all be treated as confidential and as affairs of the State and shall not be shared with the public.

On November 16, 1975, ordinance no. 22 of 1975 was enacted. It again introduced some changes to the MISA, by inserting sub-section 2A in Section 16A. All the amendments made by the order had the retroactive effect of validating all the previous laws. The afore-mentioned orders were published on January 5, 1976, under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act of 1971 (Law No. 14 of 1976).

The resultant effect of many of these amendments was the unlawful arrest and detention of many political figures throughout the nation. Most of these political figures were prominently known for their activism either against the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi or were affiliated with the opposition parties of the time.

In addition to this, most of the detained individuals were not informed of the grounds for their detainment. These detentions lasted till even after the emergency period, making many of the detainees file writ petitions in the High Courts, for release, as well as challenge the authenticity and legality of such detentions and the amendments introduced during the emergency period that allowed these detentions.

The defendants were detained under Section 3(1)(a)(ii), read with Section 3(2) of the MISA, 1971. The aforesaid legislation had been challenged in several High Courts alongside the order of the President of India dated June 27, 1975 which declared the suspension of the right to approach the Court for the enforcement of Articles 14, 21 and 22. The High Courts ruled in the favour of the petitioners, declaring the aforesaid legislation and order unconstitutional and inoperative. It invoked the annulment of the order and also pronounced the defendant’s immediate release.

In some cases, they questioned the validity of the amendments against Article 38 (State to secure a social order for the promotion of the welfare of the people) and Article 39 (certain principles of policy to be followed by the State) of the Indian Constitution. When these petitions were filed, the petitioners raised the preliminary objection of maintainability, on the ground that, for the request of release of the detained individuals, a writ of habeas corpus was issued. They contended that the accused, alleged in essence, had been deprived of their personal liberty in violation of the procedure established by law.

Only by considering Article 21 of the Indian Constitution and taking into account the presidential order of June 27, 1975, which suspends the right to request the execution of the right conferred by this Article, the petitions were rejected at the threshold. While the High Courts of Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Madras confirmed the preliminary objection, the present dispute was not favourably received by the High Courts of Allahabad, Bombay (Nagpur Bench), Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana.

In simpler words, most of these petitions were held in the favour of the petitioners, that is, the detained individuals, and not the State. One such petition was the present case, which was initially filed as a writ of habeas corpus, by the wife of Shivkant Shukla. Shukla, the respondent in the present case, was a political activist detained under preventive detention during the emergency period. He was arrested and detained without any trial for an infinite period, under the MISA.

The Allahabad High Court decided in favour of Shivkant Shukla. Aggrieved by the decision, the State appealed to the Supreme Court to challenge the aforesaid decision, along with other petitions filed by individuals detained during the emergency.

Issues raised

The issues raised before the Supreme Court of India were as follows:

- Whether a writ petition under Article 226 (power of the High Court to issue certain writs) of the Indian Constitution is maintainable when enforcing Article 21 during a national emergency proclaimed under Article 359(1) of the Constitution.

- Whether the ordinance issued by the President on June 27, 1975 was unconstitutional.

- Whether there was any scope for judicial review during an emergency.

Arguments of the parties

Petitioner

The primary contention of the petitioner of this case was that emergency provisions enshrined in the Indian Constitution empower the executive part of the government to exercise complete control over all the state affairs, in a way that stabilises the State. Since emergencies are only to be applied in situations where the sovereignty and Constitution of India are threatened, the considerations of the State and its security should take priority over individual interests and rights. Without a secure and stable State, the safety of the citizens could not be guaranteed as well.

Other than that, the petitioner also contended that the State had no obligation to release the individuals detained during the national emergency, even if no sufficient reason for detainment was to be found. Article 22 of the Indian Constitution, along with the other fundamental rights, was suspended during the emergency period and thus, any writ petition in pursuance of the same should not be valid. Furthermore, the right to approach the Court for enforcement of Articles 14, 21 and 22 was also suspended by the presidential order issued under Article 359(1).

The petitioner also argued that the suspension of fundamental rights, specifically Article 21, is a constitutional mandate during national emergencies and could not be implied as unconstitutional or arbitrary in nature. Approaching the Court for the enforcement of the same, in turn, should also be suspended since the right itself is restricted in the given circumstances. It cannot be implied as an absence of the rule of law.

Lastly, emergency provisions such as Article 358 and Article 359(1) are constitutional mandates that are necessary for the maintenance of the stability of the State during external aggression or even internal disturbances. These provisions allow the executive to gain complete control over all the affairs of the State and take necessary steps needed for the maintenance of the security of the country and its citizens.

Respondent

On the other hand, the respondent argued that Article 359(1) did not empower the executive organ of the government to make laws during the emergency period. The objective of the aforesaid provision is to unify all the powers under the government, not restrict the legislature completely. While the executive did have the power to issue ordinances and orders even in violation of fundamental rights during the emergency, the power did not extend to statutory or constitutional amendments. The principle of limited power of the governmental organs, such as the executive, was still applicable during the emergency under the system of checks and balances based on the doctrine of separation of powers.

The respondent further contended that Article 359(1) restricted the approach to the Supreme Court of India under Article 32 for the enforcement of fundamental rights, but not any of the High Courts under Article 226 of the Indian Constitution. Moreover, while the article suspended some of the fundamental rights, including the right to personal liberty under Article 21, it has no effect on other statutory and common law rights pertaining to the same. As such, approaching the Court for the enforcement of the right to personal liberty through statutory provisions should not be suspended or restricted.

In addition, the validity of the presidential order, as well as the ordinance, can only extend to certain fundamental rights as per the emergency provisions and not statutory or common law. Thus, approaching the Court for the enforcement of any statutory law or common law should not be held invalid against the presidential order.

It was also contended that Article 352 of the Indian Constitution limits the executive, legislative and financial powers of the State to cope with emergency situations such as internal disturbances, rebellions, external aggression and war. As such, the limitation of the scope of executive and legislative powers is nothing more than what is mentioned under Article 162 of the Constitution.

Furthermore, even during an emergency, presidential orders cannot restrict statutory rights, common law rights or even contractual rights. In fact, constitutional rights which are not fundamental rights cannot be restricted by such orders either since any presidential order under Article 359 (1) does not have the power to suspend any fundamental right.

The respondent also argued that under Section 3 of the MISA, the State can only arrest the individuals who have fulfilled the conditions mentioned under its clauses. Any detention that does not fulfil the same would be considered beyond the scope of the Act.

Lastly, the respondent emphasised that the Preamble of the Indian Constitution speaks of India as a sovereign, democratic and republic nation and, therefore, the State shall not act to the detriment of the citizens unless prescribed by the law. Even then, the procedure established by law shall be followed and all such detrimental actions shall be limited to the extent as prescribed.

Laws discussed in A.D.M. Jabalpur vs. Shivkant Shukla (1976)

Given below is a brief of the legal provisions discussed in the present case analysis:

Constitution of India

Article 358

Article 358 deals with the suspension of provisions under Article 19 of the Indian Constitution during emergencies. Given below are the brief of its clauses:

- While an emergency proclamation states that the security of India or any part of its territory is threatened by war or external aggression, nothing is at stake. Article 19 will restrict the power of the State as defined in Part III to make any law or take any executive action that the State would like, but the provisions contained in that Part would be competent to do or take, but any law thus made, the extension of the incompetence, will cease to have effect as soon as the Proclamation ceases to function, except that incompetence respects things done or omitted before the law ceases to have effect.

- Provided that when said emergency proclamation is in force only in any part of the territory of India, any such law may be made, or executive action of this kind may be taken under this article in relation to or in any territory of the State or Union in which or in any part from which the emergency proclamation is not operational. Further under the condition that to the extent that the security of India or part of its territory, is threatened by activities in or in relationship with the part of the territory of India in which the emergency proclamation is in operation.

- Nothing in clause (1) shall apply- (a) to any law that does not contain a recital in the sense that such law is related to the emergency proclamation in effect when it is made, or (b) to any executive action adopted from otherwise, by virtue of a law that contains said recital.

Article 359

Article 359 of the Indian Constitution talks about the suspension of the enforcement of fundamental rights by the courts during emergencies.

Clause (1) of the aforesaid Article states that when an emergency proclamation is being executed, the President may, by means of an order, declare that the right to transfer to any court for the execution of the rights conferred by Part III of the Indian Constitution (except articles 20 and 21), as may be mentioned in the order and all proceedings pending in any court for the enforcement of the aforementioned rights, will remain suspended for the period during which the proclamation is in force or for the shortest period specified in the order.

Furthermore, clause (3) of Article 359 specifies that any order made under clause (1) shall be presented before both Houses of the Parliament soon after it is made.

Meanwhile, clause (1A) deals with the power of the State to take any executive actions or make laws. As per this clause, no order made under clause (1), mentioning any of the fundamental rights conferred under Part III of the Constitution, except Articles 20 and 21, shall affect the powers of the State during an emergency. Such order shall cease to operate once the emergency ends and any law based on such order shall also cease to be enforced at the same time.

Clause (1B) mentions the exceptions of the above, stating that any law made by the State, which is not in relation to the emergency or even has any reference to the same, shall remain in effect even after the emergency ends. It also extends to any executive action taken by the State, under a law that has no reference or relevance to the proclamation of the emergency.

Essential ingredients of Article 359(1)

The emergency proclamation must be in force to declare and enforce Article 359(1). The President may order not to apply or approach a court for the application of the fundamental rights set out in Part III of the Constitution. In any order, the enforcement procedures will remain suspended for the duration of the proclamation.

Difference between Article 358 and Article 359(1)

Article 358 specifically suspends the fundamental rights enshrined under Article 19 of the Constitution, only to the extent that the legislator may frame laws despite being violative of Article 19, when the emergency is proclaimed.

Under Article 358, the executive may take any action that it may need to, under such statutes. Article 358 does not suspend all fundamental rights, while Article 359(1) suspends any ongoing proceedings for the application and enforcement of all the fundamental rights (except Articles 20 and 21) enshrined in the Indian Constitution. Article 358 is limited to fundamental rights under Article 19 only, while Article 359 extends to all those fundamental rights whose execution can be suspended by the presidential order.

Article 358 automatically suspends fundamental rights under Article 19, as soon as a state of emergency is declared. On the other hand, Article 359 does not automatically suspend any fundamental right. It allows the President to suspend the application of the specified fundamental rights based on the needs of the State at the given time. Not all circumstances may require the suspension of fundamental rights and their enforcement by the Courts.

Article 358 only works in the event of an external emergency (i.e. when a state of emergency is declared because of war or external aggression) and not in the case of an internal emergency (this is to say when the state of emergency was declared on the basis of armed rebellion). Article 359, on the other hand, applies both in the case of an external emergency and an internal emergency.

Article 358 suspends fundamental rights under Article 19 for the duration of the emergency, Article 359 suspends the application of fundamental rights for a period specified by the President, which can be either the entire duration of the emergency or for a shorter period.

Article 358 applies to the whole country, while Article 359 applies to all or part of the country. Article 358 suspends Article 19 completely, while Article 359 does not authorise the suspension of the application of Articles 20 and 21.

Article 358 authorises the state to legislate or to take any measure incompatible with the fundamental rights set out in Article 19. Meanwhile, Article 359 authorises the State to legislate or to take enforcement action contrary to the fundamental rights and its execution that is suspended by order of the president for the time.

There is also a similarity between Article 358 and Article 359. Both provide immunity from contestation, only to emergency laws and not to any other laws. In addition, executive measures taken only under such a law are protected by both.

In the present case, the oblique reference indicates that “…no freeman shall be imprisoned, imprisoned, sick or banished, or destroyed in any way except by the judgement of his own people or the law of the land.” The document is with the detainee or someone else on his behalf, so he goes to court to oppose the detention. The person or his representative must prove that the authority or court that ordered the arrest committed an error of fact or of law. It is clear that the habeas corpus appeal remains the most powerful process by which any citizen can challenge the correction of the restriction on individual liberty. Article 21 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to life and liberty of every citizen of the nation.

The right to apply to a court to enforce the aforesaid article was suspended under Article 359 when the emergency due to ‘internal disturbances’ was imposed (1975-1977). The logical question that followed was whether the Habeas Corpus order was enforceable in such a situation. The historic case of A.D.M. Jabalpur vs. Shivkant Shukla (1976) or the habeas corpus case attempted to answer this question and was at the origin of the 44th Constitutional Amendment in 1978. This amendment, adopted unanimously, guarantees that Article 21 cannot be suspended even in case of emergency.

Maintenance of Internal Security Act, 1971

The Maintenance of Internal Security Act or the ‘MISA’ Act of 1971 was quite a controversial legislation that was enforced and amended during the regime of Indira Gandhi as Prime Minister. This Act deals with the powers of the State, especially during an emergency, which includes preventive detention for an indefinite period, search and seizure of property without a warrant, along many others to curb internal disorder during an emergency. However, the aforesaid Act was repealed in 1977 due to its misuse and the facilitation of arbitrariness brought through its provisions.

Following are some of the important provisions of the Act relevant to the present judgement:

Section 3

Section 3 of the MISA talks about the power of the government to make orders detaining individuals. Both the state and the central government can make orders under this section, against any individual who is a citizen of India or even a foreigner at the time.

As per Sub-section (1) of this Section, the government can order a preventive detention of any foreign or Indian citizen if they so deem it necessary for the security of India, any of its state or public order. Such detentions can also be made to maintain international relations with another nation.

In the case of foreigners, an order specifying their status of arrangement needs to be presented with directions on whether the individual should be deported to another country or should stay within India along with regulations on the respective arrangements to be made.

Meanwhile, Sub-section (2) talks about officers such as District Magistrates, Additional District Magistrates and Commissioner of Police, and their power to issue orders under the aforesaid section during the emergency. Before issuance, such orders and their grounds given by the officers need to be approved by the state government they are subordinate to, under Sub-section (3). Once issued, the state government needs to report the same to the Central government.

Section 11

Section 11 of the MISA discusses the procedure of Advisory Boards, which is established as a statutory authority under Section 9 of the same Act. Section 10, on the other hand, talks about referencing the detentions made under this Act to the Advisory Board at the earliest.

As per Section 11, the Advisory Board has the power to hear the detained individual and their representation against the order of their detention. The board, once satisfied with the information received about the detention, can call upon the detainee for a hearing if the individual concerned desires so. Once the hearing is over, the Advisory Board will submit a report of the same to the State within ten weeks of the detention.

The aforesaid report shall also have a separate part mentioning the opinion of the Advisory Board on whether the grounds presented for the detention are of sufficient cause or not. Such an opinion would be made through a simple majority voting of members of the board.

Section 12

This section talks about the further action that is to be taken on the report submitted by the Advisory Board. As per Section 12, if the board is of the opinion that there is sufficient cause for the detention, then the State may confirm the order of the said detention and continue the detention. However, if the board finds the grounds of detention insufficient, the State has the obligation to revoke the order of detention and release the detainee at the earliest.

In the present case, however, the reference of the Advisory Board established under this statutory law was not sought nor was their opinion on whether the detentions made by the State carried sufficient ground or not.

Section 16

As per Section 16, no suit or legal proceedings can be filed against the State or any officer making the detention if such detention was made in good faith or done in pursuance of the provisions under the MISA of 1971.

Section 16A

Section 16A of the MISA is one of the provisions that was specifically made to be applied during the emergency period. It was introduced by an amendment in the Act in 1975 and mostly dealt with the procedure of detention during emergencies.

Sub-section (2) of this Section specifically talks about the enforcement of this section and the review and approval of the detentions made by the appropriate government during the emergency. If the detention of an individual is considered necessary for effectively dealing with the emergency, the State has the power to detain them indefinitely after communicating the same to the detainee within twenty days of detention under Sub-section (3).

In addition, the State also needs to reevaluate every four months whether the detained individual is still necessary for effectively dealing with the emergency. If, on reconsideration, it is held that there is no further necessity for the detention of the concerned individual, then the State can revoke their order of detention under Sub-section (4) of this Section. However, the detainee does not have any right of representation during such review or consideration. The State has no obligation to let the concerned individual know about the review and its result unless it is through the revocation of the order of detention.

What sets this section aside from the rest of the Act is that subsection (6) explicitly states that for any detention made under Section 16A, other sections of the Act do not apply the same. Sections 8 to 12 of the MISA would not apply to such detentions at all while Section 13 would apply with modification. This subsection completely sets the Advisory Board aside, which was the only check and balance stopping the State from making arbitrary arrests and unlawful detentions under this Act.

Furthermore, Sub-section (9) also states that the grounds of detention or declaration of detention order, modification or revocation of detention orders and confirmation or review of the detention — all these information are to be treated as confidential and affairs of the State. Thus, it would not be disclosed to the public or communicated even to the detainee unless stated otherwise. This not only goes against Article 22 of the Indian Constitution but also completely disregards the procedure established by law for arrests and detention under the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973.

Both these subsections completely contradict the procedures mentioned in the rest of the Act, giving the State all the power without any restriction or consideration for the rights of the detained individuals. This made Section 16A very controversial and highly probable to be misused, which it was.

On the other hand, Sub-section (8) of the Section does specify that the state government has the obligation to report and notify the central government of any detentions made and modifications and revocations that are to be made to the orders of detention. But no one outside the government and as a part of the public has been given the right to be privy to such information, even the detained individuals themselves. This limitation on information was applicable even after the emergency, making such detentions completely in favour of the State at the cost of the people’s basic human rights.

Section 17A

Section 17A of the MISA was a provision added later, in an Amendment made in 1975, to discuss the duration of detention for special cases, such as during an emergency. As per this Section, any individual (foreigner or Indian national) can be detained by the State, without referencing or obtaining any opinion from the Advisory Board for more than three months but not exceeding two years from the date of detention in certain cases, which includes preventive detention for the security of India and its foreign relations as well as any detention made to maintain public order.

The biggest issue with this Section, is that it is both vaguely phrased to have a wide interpretation that can be abused, and does not have any grounds that can specify what may be defined as disruption of public order or the security of India.

Section 18

This is another Section that was added by an amendment to the MISA, in 1975, which was both controversial and abused at its time of enforcement. As per Section 18, no individual detained as per Section 3 of this Act, either a foreigner or an Indian national, has any right to personal liberty under common law or natural law rights, if any.

Judgement of the case

Ratio decidendi

The unasked question of the present case was whether the State’s interest would triumph over the individual’s interests and rights of the citizens, especially in cases where the security of the nation was concerned. While not raised as an issue directly, this question highlighted the distinction between positive and natural law, bringing the Court’s attention to another question — which would prevail in a situation such as this?

As per the Supreme Court in the present case, just because the fundamental rights lie as both constitutional rights and natural rights, it does not make the enforcement of these rights during the emergency period under Article 359(1), invalid. It merely makes the said constitutional provision overshadowed, according to the doctrine of eclipse.

However, enshrined in the Indian Constitution, are also the provisions for the proclamation of emergency, which stand to be one of the few restrictions on fundamental rights. Since an emergency is usually only proclaimed during a necessary period when the State is either in unrest or has lost its security, the interest of the State overshadows that of the individual. Thus, in such cases, the inconsistencies observed are to be interpreted harmoniously as per the required situation.

Given the presidential order of June 27, 1975, as per clause (1) of Article 359, no one has the right to file petitions of habeas corpus under Article 226 of the Constitution, to a High Court or any other writ or order, to enforce any right to the personal liberty of a person detained under the MISA, 1971 on the grounds that the warrant of arrest or detention is for a reason not in accordance with the law, illegal or masculine. In case of emergency, the executive authorities protect the life of the nation. Article 358 of the Indian constitution also provides that as long as the proclamation of emergency is in effect, all laws, orders and executive actions in contravention of Article 19 would be considered valid.

As per the judgement held in the State Of Madhya Pradesh & Anr vs. Thakur Bharat Singh (1967), the suspension of enforcement of certain fundamental rights is prescribed only to protect the security and interest of the State and its agents in cases of emergency. The safeguarding of liberty is in the good faith of the people and in line with a representative and responsible government. If extraordinary powers are granted, they are granted because the urgency is extraordinary and limited to the emergency period. Freedom as a gift of the law, is both given and defined by the legal provisions. However, it is similarly limited or abridged by the same law.

The best example of this can be seen through the application of Article 359(1), which suspends the enforcement of any fundamental right enshrined under Part III of the Indian Constitution. Once mentioned in a Presidential Order, the aforesaid provision would be enforced throughout India for the duration of the emergency period. It does not make any distinction between the type of emergency, whether it is caused due to war, external aggression or internal disturbances. Whatever may threaten the security of the nation and warrants the need for the proclamation of emergency would be within the purview of this constitutional provision.

The purpose of Article 359(1) is to not only limit the enforcement of the fundamental rights to the legislative domain, but also to the actions of the executive branch and the implementation of the judicial proceedings. All laws relating to the fundamental rights would be temporarily suspended as well, while the ongoing judicial proceedings regarding the same would be halted from enforcement of any decree.

The Court observed that this constitutional provision limits the fundamental rights during the emergency period to centralise power in the hands of the State and minimise any lengthy proceedings that may act as a deterrent in the path to achieving public order and security of the nation. Article 359(1) achieves the said purpose by also suspending the right to approach any court for the enforcement of fundamental rights during an emergency.

It was also noted that Article 359(1) removes the jurisdiction of the High Courts under Article 226 and the Supreme Court under Article 32 for the fundamental rights mentioned in the presidential order enforcing it. Thus, based on this rationale, it can be concluded that a writ petition of habeas corpus cannot be filed before the High Court and enforced for the same.

Furthermore, Articles 352 and 359 of the Indian Constitution are exempted from any remedies in the courts even after the duration of the emergency. Since the executive action taken during the emergency falls under the rights of the President enshrined in the said constitutional articles, no remedy can be sought for any such presidential orders or ordinances.

Thus, it cannot be said that Section 16A(9) of the MISA, 1971 is unconstitutional, solely on the ground that it affects the jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226, when such jurisdiction is already removed during the emergency period. The Court also emphasised that Section 16A(9) of MISA expressly clarifies that issuing a rule of evidence does limit or affect the jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226 and therefore, it cannot be considered unconstitutional in nature.

The Court reasoned that all executive actions operate in pursuance of some law or order that acts as the authority to support it. Thus, the amendments made in the MISA, including the introduction of Sections 16A and 18 are made with the clear intention that preventive detention should be a matter controlled exclusively by the executive organ of the State.

In addition, Section 18 of the MISA does not suffer from excessive delegation and is a valid piece of legislation. Part III of the Constitution confers fundamental rights in both a positive and negative language. To contend that the aforesaid Section is only applicable to post-detention actions, is against its language. Section 18 applies to all the orders of detention that are made under Section 3 of the same Act. In simpler words, no individual in respect of whom an order of detention is made or ‘purported’ to be made under Section 3, shall have any right to personal liberty by virtue of natural law or common law, if any. Relying on the judgements given in Poona City Municipal Corporation vs. Dattatraya Nagesh Deodher (1964) and Municipal Corporation vs. Sri Niyamatullah (1969), the expression ‘purports’ will be equated to the meaning ‘has the effects of’. Furthermore, since there is no natural law or common law right to habeas corpus, Section 18 does not come under the purview of the same.

Furthermore, the Court noted that the basic structure of the Indian Constitution includes the emergency provisions enshrined in it. Thus, they are to be regarded on the same pedestal as any other part of the Constitution that defines the sovereignty of India. The limits of judicial review must be coextensive and consistent with the right of an aggrieved person to complain about the invasion of their rights. The theory of the basic structure of the Constitution cannot be used to construct an imaginary part of the Constitution that might conflict with constitutional provisions.

As held in the landmark judgement of Kesavananda Bharati Sripadagalvaru vs State of Kerala (1973), the theory of the basic structure of the Constitution is nothing more than a means to determine the intent of the framers of the Constitution while drafting the said constitutional provisions. The parts that form the essential parts of the Constitution cannot be amended or removed if they contradict the intent of the Constitution itself. However, that does not mean the basic structure doctrine could build and add a new part to the Constitution. It is a theory that can be hardly considered as anything more than a part of a well-recognised mode of constructing a document. It cannot imply new tests outside the Constitution or be used to defeat already existing constitutional provisions.

Relying on the case of Indira Nehru Gandhi vs. Raj Narain & Anr (1975), both Chief Justice of India Ray and Justice Chandrachud stressed that the principle of the rule of law demands that the powers of the executive authorities be derived, as well as limited by law. Based on this view, the Court noted that the rule of law is not applicable in the present case, since emergency provisions enshrined in the Indian Constitution themselves are based upon the same principle. All the detentions made by the State under the emergency provisions follow the due process of law and so do the detentions made under the MISA. Furthermore, even during an emergency, the restrictions on fundamental rights have been applied universally upon both foreigners as well as Indian citizens. All of this follows the supreme law of the land, the Indian Constitution.

Lastly, it was also noted that the preventive detention being placed exclusively within the control of the executive authorities did not violate the principle of separation of powers, especially since it was for a fixed duration of the emergency period. Furthermore, no constitutional provision explicitly proposes preventive detention as a judicial function. Thus, since an order of preventive detention is not quasi-judicial in nature, there could be no question of violating the principle of separation of powers by placing it within the control of the executive organ of the government.

The Supreme Court also emphasised that the Indian Constitution does not recognise the principle of separation of powers in its absolute rigidity, as also mentioned in the case of Rai Sahib Ram Jawaya Kapur vs The State of Punjab (1955). The functions of different parts or branches of the government have been differentiated sufficiently, but not severed completely. However, that does not mean the Indian Constitution assumes the function of one organ belonging to another. The executive authorities of the State can exercise the power of administration or subordinate legislation when delegated so by the legislature. This can also be seen in the case of judicial functions- that the executive can be delegated in a limited manner.

Obiter Dicta

In the present case, the Supreme Court observed that no freedom or rights are absolute in nature. All fundamental rights have some restrictions and their suspension under the emergency provisions enshrined in the Constitution is one of those restrictions.

The court also emphasised that individual rights and freedoms are given the most value and priority in judicial decisions due to their role in the development of a free and democratic nation. However, in certain cases like during the proclamation of emergency when the security of the nation and the safety of its citizens might be in question, the restriction of fundamental freedoms is often necessary for the protection of the citizens themselves.

Not to mention that the interpretation of constitutional provisions for the proclamation of emergency cannot forgo the language that clearly states that the suspension of fundamental rights is required for the same. Not supporting the provisions given in the Indian Constitution without any reasonable cause would be meaningless.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court also observed that Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, which protects the right to life and personal liberty of an individual, is also an integral part of the fundamental rights which are mentioned to be suspended under the emergency provisions of the Constitution. In a manner, the detained individuals would be deprived of their freedom under Article 21 by due process of law only.

It was also agreed upon that Article 21 was not the only depository of the right to personal liberty and that there were other statutory laws and the common law. However, as the supreme law of the land, the Constitution takes precedence over all the other laws. Accordingly, the suspension of fundamental rights including the right to life and personal liberty under the constitutional provisions for proclamation of emergency would take priority over all the other laws.

The Court also noted that while natural law may be on equal footing as the fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution, it does not override the expressed terms or language used in the statutory law. In simple terms, natural law, which is quite abstract and theoretical in nature, would not override positive law expressed through statutory provisions, which is more practical in its application.

Given below are some of the observations made by the constitutional bench of the present case, briefly highlighting the views and opinions of each member of the coram.

Chief Justice of India – A.N. Ray

Freedom, while cherished and protected, is also limited and controlled by law, either through statutory provisions or the common law. Without restrictions or limitations, one’s definition of freedom can infringe another’s. This ‘regulated freedom’, as Edmund Burke had once called it, is what we are familiar with in the current society, and not an abstract or absolute concept of freedom.

In democratic nations like India, this restriction or ‘regulation’ of freedom is derived from the faith of the people in their State, as well as their representative and government that has developed over time. Only when there is a situation of emergency, the State may grant extraordinary powers, whether for war, external aggression or armed rebellion. These extraordinary powers, which are granted to maintain the security and safety of the nation and its citizens, are strictly limited to the period of emergency and its urgency.

The only purpose of these powers is to ensure that even during a period of emergency, there is a balance between the interests of the State and the protection of its citizens, while dealing with whatever is threatening the security of the nation. This delicate balance between freedom and its regulation by the State is what showcases the maturity of a civilised and democratic nation.

Justice H.R. Khanna

The observations in the above-mentioned precedents show that the validity of the warrant of arrest could be annulled despite the presidential orders of 1962 and 1974, under Article 359, if the right was not covered by these presidential orders. The protection granted by the absolute presidents was conditional and limited to abandoning the challenge of the arrest warrants and other measures adopted under the provisions mentioned in these presidential orders with respect to the violation of the articles specified in these presidential orders.

If the detention of a detainee did not comply with the provisions mentioned in the presidential orders, the presidential orders did not have the effect of protecting the warrant of arrest and it was permissible to question the validity of the detention at the prison. The reason was not made under the specified provisions but in violation of those provisions.

Justice M. Hameedullah Beg

We can say that the Constitution is dominated by the rule of law because its general provisions consist of freedoms and rights like the right to individual liberty and the right of public assembly. These rights, based on the concept of rule of law, are protected by the constitutional provisions. Meanwhile, the other rights of private persons are presented to the courts in special cases. In many foreign constitutions, on the other hand, all the security conferred on the rights of individuals are derived from the general provisions of the constitution only.

Justice P.N. Bhagwati

There are three types of crises in the life of a democratic nation, and three well-defined threats to its existence.

The first is war, especially a war to repel the invasion when a ‘state must transform its political and social order in peacetime into a combat machine in wartime and surpass the skills and efficiency of war. the enemy.’ There may be a real war or a threat of war or preparations to deal with the imminent occurrence of the war, which can all create a crisis situation of the most serious order. The need to concentrate more power within the government and the contraction of normal political and social freedoms cannot be discussed in such a case, especially when people face the horrendous horror of national slavery.

The second crisis is a threat or presence of internal subversion intended to disrupt the life of the country and endanger the existence of a constitutional government. This activity can have various causes. Perhaps the most common is disloyalty to the existing form of government, often accompanied by a desire for change through violent means.

Another cause may be, strong dissatisfaction with some government policies. State applications within the federal government for linguistic or religious lines may fall into this category. The presence of powerful elements without law, perhaps without political motivation, but for various reasons that go beyond the scope of the ordinary mechanism of law, can lead to this problem.

The third crisis, recognized today as a measure of emergency sanction by the constitutional government, is collapsing or causing a collapse of the economy. It must be recognized that an economic crisis is such a direct threat to the constitutional existence of a country at war or internal subversion. These are three types of emergencies that can normally endanger the existence of constitutional democracy.

Justice Y.V. Chandrachud

The argument that Article 21 of the Constitution is not the only depository of the right to life and personal liberty is quite a crucial one. The said constitutional article has quite a wide interpretation, all made through numerous judicial precedents to protect the personal freedom of the people. However, that does not make Article 21 the sole repository of all personal freedom. Not all aspects of freedom of person are meant to be covered by Articles 19, 21, and 22 of the Constitution.

It is true that if any statutory law of the State mentions that no individual shall be deprived of their personal liberty except according to the procedure established by law, no presidential order can bar its enforcement. However, the premise of this argument assumes that there is legislation in the country that states the same, which it does not. There is no statutory law in India that confers the right of personal liberty by providing that there shall be no deprivation of it except in accordance with law.

On the other hand, Section 18 of the MISA clearly stated that no individual detained under Section 3 of the aforesaid Act, either a foreigner or an Indian national, has any right to personal liberty under common law or natural law rights, if any. Thus, the actions of the State are valid and in accordance with the positive law as prescribed.

Supreme Court’s verdict

The case was discussed at length for about two months by the constitutional bench of five judges before any decision was made. The Supreme Court of India reached a conclusion only after a sentencing application was filed for the present case. The judgement was ruled in the favour of the petitioner, that is, the State, with the majority view passed by four members of the constitutional bench while Justice H. R. Khanna gave the dissenting opinion.

As per the majority opinion, it was held that the presidential order given on June 27, 1975, was constitutional and valid. Thus, in the view of the presidential order, no individual had the right to approach any court even through a writ petition to the High Court under Article 226 for the enforcement of fundamental rights that were suspended during the emergency. Any petition challenging the legality of any direction or order of detention on grounds of discrepancy with other statutory laws or common law or any unlawfulness was to be dismissed.

The Supreme Court held that all habeas corpus petitions previously filed under the various High Courts would not be maintainable as per the presidential order and were to be, thus, dismissed or recalled. The validity of the MISA of 1971 was also upheld, with its provisions like Sections 16A, 17A and 18 held constitutionally sound.

For the scope of judicial review during an emergency, the Court held that judicial review also has its limits, which should be coextensive and consistent in nature. As such, the Court cannot give the constitutional provisions an interpretation that is distinct from its wordings and not supported by its language. Furthermore, not supporting the provisions given in the Indian Constitution as they are expressed without any reasonable cause would be meaningless.

As mentioned earlier, the dissenting opinion was given by Justice H.R. Khanna, who stated that enforcing Article 359(1) may suspend the right of an individual to approach the Court for enforcing fundamental rights but not their statutory rights or the rights under common law. As such Article 21 is not the only provision that protects the right to life and personal liberty of an individual. Many other statutory laws and even the common law can act as a repository for the same and should be allowed to be enforced even during the period of emergency.

Justice Khanna also emphasised that the State does not have the power to deprive an individual of their right to life and personal liberty without following the due process established by law. This also applies during the proclamation of emergency. While Article 21 may lose its procedural power during the emergency, the substantive power still persists.

Analysis of the judgement

The judgement passed by the Supreme Court in this case has been criticised widely for decades, marking it as a black spot in the Indian judicial history. Instead of upholding the rights of the citizens, the judgement prioritised the interests of the State with a flawed interpretation of the constitutional provisions. No further remedy was provided to the detained individuals either, until the State released them on its own and not on account of the present judgement.

The right to life and personal liberty are one of the crucial parts of the natural law and are universally accepted to be inalienable from human life. Without this right, no individual can develop or grow to their full potential. It is the most widely interpreted constitutional provision and has been well known for acting as an umbrella for other rights that are not explicitly mentioned in the Indian Constitution.

To suspend such a basic human right would be encroaching on the very principle of democracy, as seen in the case discussed above. During the emergency period proclaimed in 1975, many individuals were detained for years and were not freed until much after the emergency was over. Most of these individuals did not even have any grounds to be detained, and even if they did, none were made aware of these grounds which were against the due process established by law.

While Article 21 of the Indian Constitution enshrines the right to life and personal liberty as a means to protect it, the said right was not conferred by the State on the citizens in the first place. The Constitution did not create this right. It existed even before the Constitution existed. Each human was born with these rights, as per the theory of natural law. Thus, when the State did not create the right to life and personal liberty, they also did not have the authority or power to suspend this right either.

For a democratic nation to have suspended the right to life and personal liberty of its citizens, while also not allowing them any means to enforce the same, is an oxymoron of the highest degree. A country cannot claim to be democratic and then deprive its people of their basic human rights without any reasonable or legal justification. Unfortunately, this is what happened in the present case and the Supreme Court of India failed to highlight the injustice of the same. Instead, the Supreme Court upheld the validity of the executive actions taken during the emergency period, completely overlooking the harm that came to the citizens because of it.

Prioritising the interest of the State above the citizens’ rights and safety is not something one would expect from the Supreme Court, especially since the judicial system is also famously acclaimed as the ‘guardian of the Constitution’ and has a history of supporting citizens through judicial activism. The present judgement not only dismissed the natural rights of the citizens, but also compromised the doctrine of the rule of law.

Furthermore, Article 358 was broader in nature, with the fundamental freedoms under Article 19 being suspended as a whole, while Article 359 did not suspend any fundamental right. The primary purpose of Article 359(1) was to prohibit the referral to the Supreme Court under Article 32 to enforce certain fundamental rights. This constitutional prohibition has no effect on the enforcement of the common law and statutory rights to personal liberty before the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution.

Even though Article 359(1) of the Indian Constitution grants the executive almost unlimited special powers to suspend Part III of the Constitution temporarily for the period of emergency, it does not affect the essential element of the sovereignty of the separation of powers, which leads to a system of checks and balances to limit the power of the executive. The suspension of fundamental rights were not intended to tip the balance in favour of the executive, to the detriment of the citizens of the country.

In addition to that, the presidential orders imposed are valid only for fundamental rights and do not extend to natural law, common law or legal rights. Applying the same is both overreaching and out of the scope of any order that can be made by the State.

It is also to be noted that in many places, the judgement equates the State and the executive as the same, especially with regard to emergency provisions. This equation of State and executive is very wrong and flawed. The executive is only one organ of the government that forms the State. Interpreting the executive as the sole representative of the State is both constitutionally invalid and arbitrary in nature.

The only consequence of the suspension of fundamental rights or their application is that the legislator can create laws that go against these fundamental rights and that the executive can apply them. This should, at no time, be interpreted as the right of the executive to violate court decisions and previous legislative mandates. A proclamation of emergency should not be used as an excuse to violate the fundamental rights of the citizens at leisure.

Moreover, the executive can only act for and against its citizens within the limits set by the laws in force. Article 352 or the proclamation of emergency does not in any way increase the scope of the executive powers of the State in relation to what is enshrined in Article 162 of the Constitution.

Finally, the State and its agents have the right to arrest only if the alleged act of detention falls within the scope of Section 3 of the MISA and all the conditions that it contains are fulfilled. If a condition remains unfulfilled, detention is considered as beyond the powers of that Act. The most important objective of constitutionally entrenched constitutional rights is to make them enforceable against the State and its agencies through the courts.

In the present case, the High Courts of several states complied with the Supreme Court’s order in silence. The Supreme Court had silenced them and they had no option but to comply and follow. This day was later called ‘the darkest day of Indian democracy’ and rightly so. There are several similarities between this trial and Hitler’s mode of operation and his accession to power. The emergency proclamation, at the request of Indira Gandhi, suspended the elections and limited fundamental rights.

The most significant example in the history of a ‘rule by decree’ is the Reichstag Decree on the Fire of 1933. Adolf Hitler convinced German President Hindenburg to issue a decree indefinitely suspending all basic civil rights. This paved the way for the suppression of opposition by the Nazis and the government of a single party of the Third Reich.

Niren De, the Attorney General of India from 1968 to 1977, had calmly answered the uncomfortable questions put forth by Justice Khanna when the comparison with the Nazi holocaust was brought up. He gave the example of another case where Chief Justice A.N. Ray almost reprimanded the inmates’ lawyer who had built Nazi gas chambers to prove their statements. He argued that any government order declared during the emergency cannot be challenged and comparing it to the holocaust is absurd.

As per the words of Justice H.R. Khanna, pre-trial detention and detention without trial are two rights that are fundamentally opposed by those who support and cherish the right to personal liberty. However, all three are important, even when they are contradictory in nature. Thus, to strike a balance, the Indian Constitution includes provisions that explicitly deal with preventive detention and the safeguards against it to prevent any abuse of this power. These provisions empower the detainee to certain rights and minimise the severity of such detentions. Despite these measures, the balance between the two opposing viewpoints of the security of the State and the personal freedom of its citizens is yet to be achieved.

Even in the absence of Article 21 in the Indian Constitution, the State does not have the power or authority to deprive an individual of their right to life or personal liberty without the authority of law or the procedure prescribed by it. This is one of the crucial parts of the doctrine of the rule of law, without which no nation can call itself democratic or civilised. Any authority with such power would become absolute and arbitrary in nature. Without the sanctity of life and freedom, there will be no distinction between a lawless society and a law-governed society.

Significance of the case

As mentioned earlier, this judgement came as a regret to many of the members of its constitutional bench, especially since it turned out to be a black spot in judicial history after reducing the scope and importance of the fundamental rights enshrined in the Indian Constitution. The present judgement received a lot of criticism for going against the previous decisions of the High Courts or various Indian states, especially since four out of the five judges had held it in the favour of the State, despite the blatant violations of basic human rights.

Even the single dissenting opinion presented by Justice Khanna did not play much in his favour. Since the dissenting view was phrased strongly against the State due to the suspension of Article 21 and their abuse of the provisions for preventive detention, it caused an uproar that significantly affected his career. The records indicate that the night before the announcement of the judgement, he informed his sister that he had made a decision and that he knew that it would cost him the seat of the Chief Justice of India.

The other four members of the constitutional bench, Chief Justice of India A.N. Ray, Justice Beg, Justice Chandrachud and Justice Bhagwati could not avoid the unscrupulous favour of the government in power. Justice A.N. Ray, with his controversial appointment as Chief Justice of India by Indira Gandhi, replacing three high-ranking judges, revered the same ground on which she walked.

Meanwhile, Justice Bhagwati had lifted the torch of individual liberty, only to fail to stand for it when it was needed the most. Later in 2011, he expressed his regret in going with the majority opinion in the A.D.M Jabalpur case, stating that the judgement of the aforesaid case was short-sighted and went on to apologise for it. Records also indicate that in 1979, after Indira Gandhi came to power, he wrote her a letter in which he expressed his admiration for her iron will and asked her to continue her reign with the same will. He later became the president of the Supreme Court of India in 1985 and held the office as Chief Justice for eighteen months.

Ironically, once the emergency ended and so did the reign of Indira Gandhi, the stance of the Supreme Court also seemed to change. The priority was again given to the civilian rights, and most judges, as discussed above, expressed their change in opinion with regard to the present habeas corpus case. Due to the change in opinion coinciding with the change in the political scenario in India, the majority of judges in the present case were accused of encouraging and facilitating the State apparatus by the public.

This was especially because of the fact that the rationale behind the judgement of the A.D.M Jabalpur case could be boiled down to all the rights enshrined in the Indian Constitution being a product of positive law, rather than a mere legal acknowledgement of the already existing natural law. By not recognising the right to life and personal liberty as a natural right that cannot be alienated, positive law was given the upper hand, which in turn increased the power of the State even more.