A hardworking paperboy in Winnipeg, Canada to a jet-setting, big spending CEO in NYC. The world where numbers have significance only if they are followed by nine zeroes and preceded by dollar mark. A bidding war and boardroom drama. Sounds like a movie? Well, yes, but this is not one of your usual John Grisham’s thrillers made into a blockbuster, but a movie based on one of the ‘serious’ and most heavyweight business books. The book deals with one of the greatest takeover battles ever, and while the film may or may not attract the average movie goers, the book has some serious honey for budding corporate lawyers (and even veterans). We bet you’d like the movie, but don’t skip reading it either.

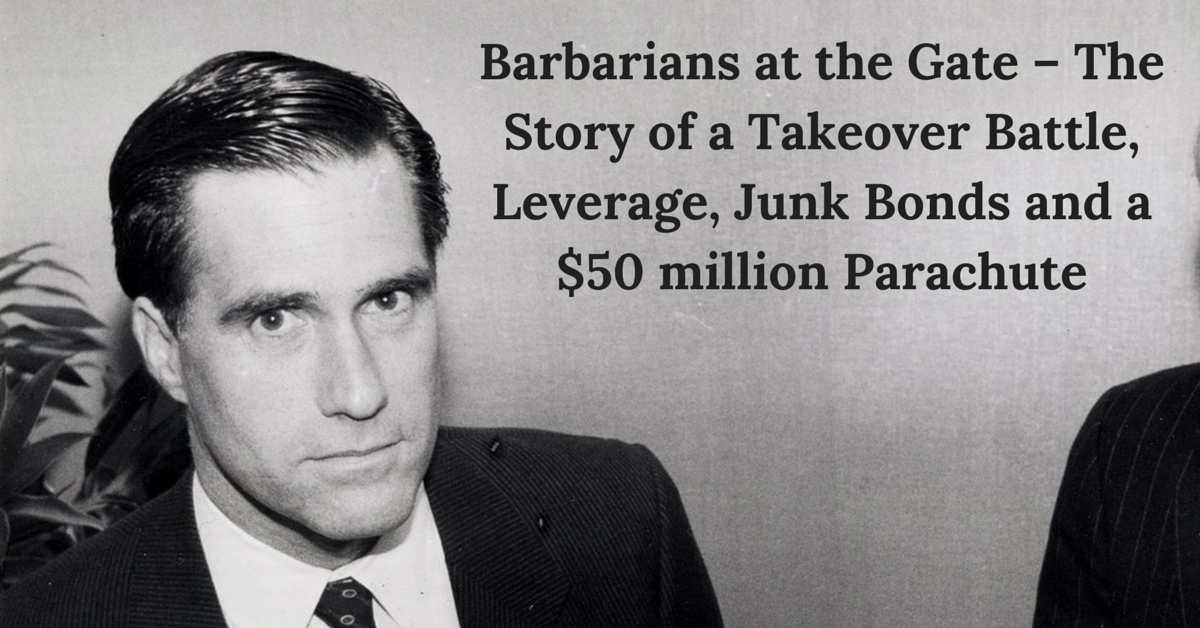

Without further ado, in today’s post I and Ramanuj shall deal with the 2nd book of the series, as promised earlier – Barbarians at the Gate, which has often been called the greatest business book of all time. The characters of this drama, as it is so common in the corporate world, were driven by an intense fervour for money, fame, power and the desire to be the best. They used fiercest of corporate strategies and the most sophisticated tools of financial wizardry. It did not matter that these strategies and tools had not been tested previously on such grand scale before, and no one knew what could ensue. The book has remained a favourite of many corporate lawyers and is widely recommended. With this post, we hope to introduce the book as well as a few concepts of takeover law and finance along with a great story of corporate profits and corporate ego.

The Cookie

Providing a background to the company and its chief executive is necessary. The book is about one of the biggest corporations in the United States of America in the 1980s – called RJR Nabisco. The company itself has been the product of the merger of two smaller companies – RJR, named after R.J. Reynolds, which manufactured cigarettes, and Nabisco – which was the leading maker of biscuits and cookies in America.

The CEO who loved ‘The Good Life’

RJR Nabisco was led by Ross Johnson, a man who had grown from rags to riches using his superb interpersonal skills – he knew when to be nice when to flatter, and how to persuade people. He was an incredible salesman. In a way, he was epicurean as well – he would party hard and binge drink late into the night with his favourites. Over a period of time, he had grown to become the chief of this corporation which held a very important place in the US corporate world. He was quite unorthodox in his behaviour – he would hate presentations and formal studies by his employees projecting the future growth of the company, which ran completely contrary to conventional wisdom.

A Dangerous Habit

The book gives an interesting name to a particular species of corporate activity where change is made for change’s sake – ‘shit stirring’. If there was nothing eventful happening with his company, Ross Johnson would get into shit-stirring mode: relocating workforce and managers, shuffling departments, changing something or the other. In the age of specialisation, it was really difficult to see how this could work – simply put, somebody’s ability as a maths genius doesn’t necessarily translate into a similar genius in poetry. Nevertheless, Ross was able to get things done the way he wanted, and also gave out the impression that something revolutionary is being done. It is very important for shareholders to watch out for ‘shit-stirring’ – a very active manager may be nothing but a shit-stirrer.

How Stock Prices work – and why they can be a CEO’s Nightmare

Every CEO closely tracks the price of his company’s shares on the stock market. The price of a company’s shares is determined by how much the company’s shareholders feel it is worth, and how much those who are looking to buy its shares are willing to pay for it. If people do not believe the company is doing well, few people will want to buy its shares, its present shareholders would like to sell its shares, and as a consequence, the share price will fall.

If, however, the company is doing well, a lot of people will want to buy its shares, and its existing shareholders will want to hold on to the shares, so those who want to buy the shares will have to pay more to exist, shareholders, and hence stock prices will rise. A CEO tends to assess his performance from the way the stock prices of his company move.

The Curious Case of RJR Nabisco

RJR Nabisco was a slight deviant from this expected behaviour. Although the company was doing well and its performance improving, its stock price remained low. A possible reason for it could have been that the market really did not expect tobacco companies to be very profitable in the long run, they expected some sort of anti-tobacco legislation that would make the companies’ operations less profitable by imposing higher taxes, or in some way disincentivise the manufacture of cigarettes.

If a company’s shares have a low price despite the fact that it is performing well, it can be vulnerable to an outsider buying such a large chunk of its shares that it can control the company. This is known as a ‘takeover’ in business jargon. Ross Johnson was worried about an imminent takeover. If somebody else took over his company, his position as the CEO would be threatened, particularly because he may not be able to justify a large part of his own expenses sourced from the company’s revenues (this, obviously, is another persistent malady in the corporate world – public companies being milked in form of unjustifiable corporate perks which can include anything from a private jet to a luxury yacht and these days, ‘bonuses’).

After a takeover, the new owner would try to cut costs and maximise his profits. In order to ward off such a threat, Ross Johnson thought that the best idea for him would be to buy the company himself. This would have put an end to his palpitations about the price of his company’s stock and let him breathe in peace. He could then focus on the long-term goals of the company.

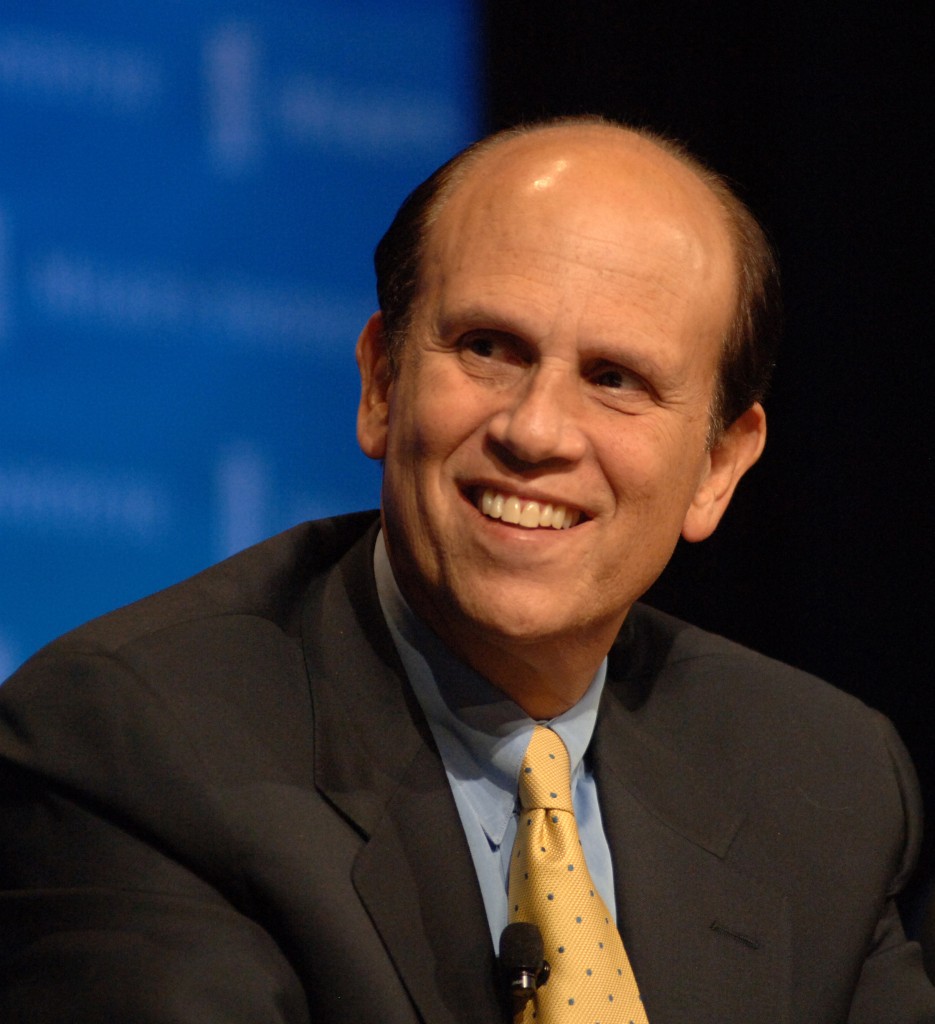

To buy the company, Ross Johnson would have had to buy off most of the shares from its existing shareholders. RJR Nabisco was a listed company, as we know, which means that its shares were traded on stock exchanges. After Ross Johnson would complete buying its shares, the company would not be listed anymore as all the shares would be held by him and his group. The process is known as taking a company ‘private’ in business jargon. This was in the line of the philosophy preached by takeover finance legend Michael Milken of investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert.

Milken and his followers in the Wall Street believed that companies controlled by a manager-owner perform much better than companies managed by professional managers mandated by a fractured majority of small and dispersed shareholders. This philosophy justified highly leveraged takeovers that often wrecked the financial stability of a company and hence were highly criticized at that time in the media as well as the Congress.

An introduction to the Leveraged Buyout

One may wonder how it is possible for an ordinary CEO to buy out a company of a size such as that of RJR Nabisco, one of the biggest in US at that time. The answer was found in the 1980s in a technique, known as the Leveraged Buyout (LBO) which was in vogue for doing such transactions. This implied raising a huge loan against the target company’s assets – factories, machinery, etc. as some form of security by promising very high interest yields. Large amounts of fund could be mobilised by this method as was demonstrated in several deals prior to that of RJR Nabisco. Since Ross Johnson was at the helm of affairs, he was in a position to do this, subject to the other directors’ affirmation.

Note that such a large amount of loan would have required tremendous cash to be paid off as interest. That, however, was not a problem, as RJR had strong annual cash earnings, generally called cash flow. The cash could be used to pay off the interest on the loan. An additional feature of a leveraged buyout is that some of the businesses of the company are sold immediately upon buying it out, so as to generate some immediate source of money to pay the most short term debts with higher interest, and keeping the long term debts with more borrower friendly terms for regular servicing from the cash flow of the company. Generally the most unwieldy businesses or those which fall outside the core competence of the company are sold first for paying off debts.

A company which may find itself facing a leveraged buyout is generally one whose stock price is undervalued – that is, where investors in the market, for some reason, believe that the company’s worth is not much and hence, there is less demand for its shares than there should be if perfect information was available to the market. Another way of looking at a company worth buying is when the replacement value of the company’s assets, that is, the price one would have to pay to buy similar assets individually from the market, is less than their value on the books of the company.

Successful completion of an LBO is usually followed by selling off its assets (factories, machinery, the manufactured stock, etc.) that individually would yield more money than selling off the shares of the company. Further, all attempts are made to cut costs of the company – any expenditure by the management which is may be too high and unjustified – such as corporate jets, and limousines, when they are not necessary and only for the ‘glamour’ quotient, is sought to be cut.

Often, those who complete an LBO do not want to keep the company forever. When the amount of indebtedness reduces and the operations of the company seem profitable again, it’s shares can be sold on the stock exchange again. This often happens at a very large premium, and is the primary source of profit for those who do an LBO.

Ross Johnson’s Customised Formula for his LBO

Strangely enough, Ross Johnson did not have any of the plans to cut costs on his mind – in fact he was expecting a very handsome remuneration for himself and his favourites pursuant to the LBO – twenty percent of the profits, which was about 2 billion US dollars!

The armoury of the Leveraged Buyout – the Junk Bond

Corporate enthusiasts may want to know some more on how a Leveraged Buy-Out works. Think of a simple marketplace. One buys what they can afford, and if they dont have enough money to buy, they don’t. With introduction of debt financing, one may also take a loan from a bank when they don’t have enough money on their own with the condition that they will pay a higher amount back in the future. Taking a loan makes sense when there is a possibility that one would make profits by deploying the borrowed money in some sort of business or transaction. The amount taken as a loan leverages the original money one had for investment, and one can keep the extra profit earned by deployment of the extra capital received as a loan as long as he pays back the loan with interest. This means one’s earning to capital ratio can drastically increase if they deploy borrowed capital and make profit in the transaction. The loan here works like a lever, multiplying the ability of the original capital to earn profits. More will be explained about leverage towards the end of this post.

A leveraged buyout implies that a very large proportion of the money paid for buying the company is essentially borrowed money. Leveraged buyouts were popularised and made possible by the acumen of a person named Mike Milken, who worked for a firm called Drexel Burnham Lambert and transformed the Wall Street in the ’70s and ’80s with his innovative financial tools and strategies, and made money like no one ever did.

The money in an LBO was raised at a really high rate of interest. This is because it was really risky, and if anything went wrong with the company, the money may not be repaid. Therefore, it had to offer high interest, so as to compensate for the increased risk. This is a fairly simple principle and it applies to ordinary transactions as well.

The instrument through which it was borrowed came to be known as a ‘junk bond’ – signifying that it could be, on account of the risk, a worthless piece of debt! Junk bonds were very popular for quite some time, as they offered huge returns to investors, and in the hands of Milken, it worked like magic.

Who are the Barbarians of the 1980s?

The analogy in the book is taken from the war between the Greeks and the barbarians of Dardania in Iliad, a mythological work of the famous Greek poet, Homer. The reference to barbarians, is used to allude to the firm KKR (named after its founders Kohlberg, Kravis and Roberts), presumably because of the unprecedented scale of the transaction – eventually they agree to buy the company out for 25 billion USD (and that is at the price levels of the late 1980s), which is still one of the largest LBOs of all time. The previous similar transaction was only about one-fifth the value of the present one. The biggest till date is LBO of TXU in 2007 ($45 bn), done by none other than Kravis.

Such a huge amount is astounding also because KKR, in this case, is not with the management’s side but against it, and hence there is complete lack of knowledge of RJR Nabisco’s internal affairs. KKR was never really told about how exactly the company is managed, and how it could be made more efficient, except for one isolated instance described in the book. They merely have some of their financial records, which can disclose numerical figures but fail to indicate the long-term value of a company. Numbers and financial statements can always be tweaked within the legally permitted boundaries, but they are seldom an accurate source of, say, whether employees are working optimally and how their morale and enthusiasm could be increased so that their output is better, and other such factors.

Initially, KKR, led by Henry Kravis in this deal, resented that Ross Johnson did not instruct them as his advisors, and instead consulted their smaller competitor – Shearson Lehman. KKR, of course, knowing that this would be the deal that would catapult their firm into a completely new league, decide to get into the fray nevertheless. They teamed up with Drexel Burnham Lambert, who were best equipped to raise junk bond debt, the magic money of that era, to launch a bid for the company.

A Clash of Egos, and Breakdown of Cooperation

Ross Johnson, however, noticed that KKR clearly have an edge in such transactions, and all of them – Johnson, his advisors Shearson Lehman and KKR, tried really hard to find a cooperative solution. However, talks repeatedly broke down over every kind of issue, big or small, but the key bone of contention remained the relative share that each advisor would take, both wanted a larger share of the pie for themselves, neither wanted to play second fiddle.

Corporate Strategy: KKR’s preemptive instruction, and a Master Dealmaker’s Hidden design

KKR were really eager to see that they get this one right, and hired the best of lawyers and investment bankers. Every side which made a bid, and every advisor to a side, had their own lawyers, which meant that a large number of America’s Wall Street firms were all engaged in the same deal at once. One firm left out in the fray was that of Bruce Wasserstein, an investment banker, probably the greatest deal maker of the 1980s.

KKR hired the services of Bruce Wasserstein (who has been called the Grandmaster of the Mergers & Acquisitions, or M&A era in the book), if not for assigning him a specific role, at least so that he was not instructed by a competing bidder, as they believed that his strategies could foil their plan. Lawyers too, were instructed just so that they are not hired by the opposing side. More on this is to come in the 4th post of this series on Skadden, as this was a common practice as far as Skadden, Arps was concerned.

Bruce Wasserstein was worried that KKR may pose a problem for him, on another deal that he was involved in – the Philip Morris (maker of Marlboro cigarettes) takeover of Kraft, if KKR decided to participate as a competing bidder. He knew that KKR could only be involved in one deal at a time. He played a very nifty move – he leaked out the some of the details of KKR’s plan to the media – so as to make KKR commit to the RJR deal. KKR could not in that case, participate in the bid of Philip Morris for Kraft. He had ensured that his battlefield was safe. In any deal, timing and the element of surprise is of paramount importance, which is why KKR did not take the leak too lightly, although it took them some time to find out who had caused it.

The Global Search for Banks and Lending Institutions

It’s interesting to see how the size of the deal was so big that at the time of launching their bids each bidder went on a global search for all the banks available, afraid that the number of banks capable of such a deal would be too few, and even amongst those who were capable, they may be hired by a competing bidder.

The Bidding Process

The strategies played at the bidding process were commendable. There were two ‘formal’ rounds of bidding – it was interesting to see how KKR suggested that they would pull out of the process, which made their competitors bid relatively low. At the end, they surprised everyone when they go for a clean sweep and bid really high. Their plan was not completely successful, as Ross Johnson’s group bid again, and there were more bids given by each side to match the other.

The bidding process was skilfully handled by Peter Atkins of Skadden, who was worried that any mishap during the same could lead to a headline making lawsuit, complicating matters for everyone involved as things would spiral out of control.

Takeover Defenses – The Golden Parachute

If the management of a company wants to shield it from potentially unwanted acquirers, it may enter into a contract stating that a certain minimum amount (which is normally very high) must be paid to it by the company, in case of unilateral removal. This is known as a golden parachute. The presence of such golden parachutes for the key managerial personnel of a company can increase the price an acquirer may have to pay by a huge amount, and thus discourage unwanted suitors. Ross Johnson’s golden parachute alone was over 50 million US dollars at that time, which he exercised, once his group lost the bid to KKR.

Winner Takes it All?

It can’t be said that the loser of the battle gets nothing. Bruce Wasserstein, who had been part of the firm known as Credit Suisse First Boston (CSFB), had left the firm with a colleague to found his own firm, named Wasserstein Perella. Since his departure, the mergers and acquisitions department of the firm had been faring unremarkably. It was upon the team at CSFB to dare and do something new, and put their firm back onto the map of great merger firms.

They did that by exploiting a loophole in the tax laws, which enabled them to present a very high bid. In fact, the bid was so high that Skadden, as the firm managing the auction, was instructed to evaluate its feasibility. Interestingly, that loophole had also been figured out by a partner at Skadden, who affirmed that the tax aspect seemed genuine. The bid, however, could not sail through as there were doubts whether the proposal could be implemented on time, but that was sufficient for CSFB to get numerous merger deals afterward, and recover from the shadow of its alumnus Bruce Wasserstein.

On the other hand, the book describes how KKR’s challenge began after it won the company, when it had to make it more profitable and repay the debt. It took quite some time, and was not an easy task.

The Follow Up

Some of us may be familiar with KKR, but many of us in India heard of them when they made news for contemplating a significant investment (well, not of the kind they did in the 1980s, and not for doing an LBO) in India’s leading coffee chain, Cafe Coffee Day (CCD).

A large part of RJR Nabisco’s business was sold off to Kraft. This has been in the news, as Kraft has also been involved recently in the takeover of Cadbury (the maker of the famous Dairy Milk and Bournville chocolates).

Problems with the technique of Leveraging

As already explained, leverage simply refers to debt. The problem with using a lot of debt for doing operations is that it acts as an amplifier – it multiplies the risk of profit and loss, so if there are profits, they are much higher than they would have been without the leverage, and losses much more devastating. For example, if I invest Rs. 100 in stock, and its value increases by 20 percent, I gain Rs. 20. However, if I borrow Rs. 900 over my money, and invest a total of Rs. 1000, the same increase shall yield a profit of Rs. 200 – which is in fact double of what I had invested. Now I can comfortably pay back the debt and keep highly enhanced profits. However, if there is a loss of 20 percent over the same amount – if I had invested Rs. 100 of my own, it would still left me with Rs. 80, but with Rs. 1000 as my investment, my loss is Rs. 200, which is double of my owned amount of Rs. 100. In other words, as investment bankers would call it, I would get ‘blown up’. Leverage played a major role in contributing to the current financial crisis and in going down of banks such as Bear, Stearns.

The book is unique in that it portrays the history of every institution involved in the takeover in great detail, and puts it in perspective. It is extremely well-written and much longer than the previous book – try it out for yourself to experience its unique flavour. Do come back next week for the write-up on Liar’s Poker and Wall Street Meat, which showcase investment banking firms of the 1980s and the 1990s and the practice of law the flourished around them.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications

With this post, we hope to introduce the book as well as a few concepts of takeover law and finance along with a great story of corporate profits and corporate ego.Junk bond King

I hope it reaches your targetted audience.The world where numbers have significance only if they are followed by nine zeroes and preceded by dollar mark.

With this post, we hope to introduce the book as well as a few concepts of takeover law and finance along with a great story of corporate profits and corporate ego.Junk bond King

I hope it reaches your targetted audience.