This article is written by Srishti Kaushal, a first-year student in Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Punjab pursuing B. A. LLB (Hons.). It explains the rights given under Article 32, 33 and 34 of the Constitution of India. It also explains the right to constitutional remedies along with different types of writs available and the power of judicial review which the courts possess.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The Indian Constitution guarantees 6 fundamental rights to the citizens of India. This includes the right to equality, right to freedom, right against exploitation, right to freedom of religion and cultural and educational rights. The makers of the Constitution recognised the importance of these rights for preserving individual rights, building equitable society and establishing a welfare state.

They also observed that merely enumerating these rights in the Constitution is not enough to ensure their practical execution. Thus, to ensure that fundamental rights are not merely paper-based, they also provided for the Right to Constitutional Remedies as a fundamental right in Article 32 of the Constitution.

To know more about right to constitutional remedies in brief, please refer to the video below:

The former chief justice of India, PB Gajendragadkar had observed that Article 32 is a “very distinguishing feature of the Constitution and serves as the cornerstone of the democratic establishment promised by the Constitution.” Clearly, the right to Constitutional remedies is a very important right granted to the citizens as it provides the citizens:

- This right allows the citizens of India to move to the Supreme Court if any of their fundamental rights are violated.

- It also empowers the higher judiciary to enforce these rights by issuing various writs.

- It has also been decided that, unless expressly provided by the Constitution, this right can only be suspended as and when the Supreme Court decides. This means unless a national emergency is declared, only the Supreme Court of India has a right to suspend this right.

The significance of this Article is such that Dr.B R Ambedkar considered it the most important Article of the Constitution without which the Constitution would be a nullity. He considered it as the soul and heart of the Constitution.

Power of Parliament to enlarge writ jurisdiction of the Supreme Court: Article 139

Article 139 of the Constitution enlarges the writ jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. It increases the scope of Article 32. This is because unlike Article 32 which only allow the Supreme Court to deal with cases involving a violation of fundamental right, this Article states that the parliament can confer additional power upon the Supreme Court.

Through this article, the Supreme Court is empowered to issue different writs for enforcement of any right other than that mentioned in Article 32(2). This means, that if the parliament allows, the Supreme Court can issue writs not only for the enforcement of fundamental rights but also for other Constitutional and legal rights.

For instance, though the Right to property is not a fundamental right, under Article 139, if the parliament allows, the Supreme Court can issue writs for enforcing the violation of the right to property as well.

Articles 32 and 226: Judicial Review

The Constitution of India is considered to be the most supreme law of the land. The Supreme Court has been conferred with the power of upholding its supremity by interpreting and protecting it.

Judicial review refers to the power of the judiciary to interpret the Constitution and to declare void any legislative order or law which is not in conformity with the Constitution. This power has been given to the Supreme Court under Article 32 and to the High Court under Article 226 of the Indian Constitution.

According to these Articles, if the provisions of a law passed by the legislature go against the provisions of the Constitution, Supreme Court and High Courts have the power to declare them void to the extent of such contravention.

Features of Judicial review

- The power of judicial review can be enforced in respect of laws, orders, and ordinances passed by both Central and State Government.

- Judicial review cannot be used for interpretation of laws incorporated in the ninth schedule of the Indian Constitution which provides certain land reform laws.

- Judicial review does not apply to any political issue.

- Judicial review is not applied by the Supreme Court automatically. Rather this power is only enforced when :

- Any law or rule is specifically challenged before the Court or,

- The validity of a particular law is challenged before the Court during the hearing of a case.

- When a law or a part of the law gets rejected as it is unconstitutional as a result of judicial review, it ceases to operate from the date of judgement.

To understand this provision better, we must refer to some case laws.

Appointment of CVC- Quashed

In the case of Centre for PIL v Union of India, a petition was filed under Article 32 of the Indian Constitution. It questioned the appointment of Shri PJ Thomas as the Central Vigilance Commissioner. He had been accused of playing a big role in the cover-up of 2 G Spectrum allocation and was thus accused under the IPC and the Prevention of corruption act, 1988. The petition argued that the courts must exercise judicial review and remove him from the post as he was unfit for it.

The court held that the judiciary cannot try to make merit review and it must limit itself to only making judicial review. To do this the court said it would only consider the legality of the appointment. As per Section 6, subsection 3 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, the CVC can be removed if he has been convicted for an offence which causes people to raise moral questions. Keeping this in view, the Supreme Court quashed the appointment of Shri PJ Thomas as the CVC.

State of W.B. v. Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights, West Bengal, AIR 2010 SC 1476

In the case of State of West Bengal v Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights, the petitioners had filed a special leave of appeal in the Supreme Court against an order made by the High Court of Calcutta under Article 226. In the order, the Court allowed the Central Bureau of Investigation to take over the investigation of state police, because the state police have made no active efforts to investigate the alleged offence.

Moreover, the court had held there was an allegation made that the lack of effort by state police was because the ruling party was trying to save its image, and thus, to uphold the principles of justice the investigation should be handed over.

The question of law which arose was whether the High Court can direct CBI, which was established under Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, to investigate a cognizable offence which occurred in the territorial jurisdiction of another state, without the consent of that state.

The court held that in exceptional circumstances, the High Court can direct the CBI to investigate an offence which lies in the jurisdiction of the state through the power of judicial review. This is important so as to ensure that the fundamental rights of citizens are upheld and those who violate it are appropriately punished (in this case the Article 21 as many lives were arbitrarily taken away), and no statutory provision curtails the court’s power of judicial review.

Pratibha Ramesh Patel v. Union of India, AIR 2013 SC 1561

The case of Pratibha Ramesh Patel v. Union of India highlighted the judiciary’s power to prevent the misuse of Article 32. In this case, the petitioner filed a petition to declare certain provisions of the Security Interest and Recovery Debt Laws Act, 2012 as unconstitutional as these provisions brought multistate cooperative society under SARFAESI Act. He argued that doing this was beyond the powers of parliament and encroached upon the powers of the state legislature, thereby undermining the federal structure of the Constitution.

The court observed that a similar writ petition had already been filed by the petitioner in the Bombay High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution. Further, it was also observed that though the petition was still pending under the High Court, it had given an interim order which had worked itself out.

The Supreme Court dismissed the petition and asked for compensation of Rs. 1,00,000 from the petitioner. It said that if such a remedy has been invoked in the High Court, another writ petition on an identical set of facts cannot be filed in the Supreme Court as it results in wasting the time of the Court.

What is a Writ?

In its earliest form, a writ was simply a written order given by the English monarch ordering a specific person to perform a specified action or task. In common law, it refers to a formal written order issued by a judicial body.

In India, the power to issue a writ is given to the Supreme Court under Article 32(2) and the High Courts under Article 226. However, the high Courts have a broader power in this regards. This is because, the High Courts can issue writs for enforcement of all rights ( including fundamental rights, Constitutional rights and other legal rights) granted to a citizen. But, the Supreme Court can issue writs for enforcement only of fundamental rights granted to the citizens.

For instance, in the case of Narayan Prasad v. State of Chhattisgarh, two brothers approached the Chhattisgarh High Court under Article 226 for enforcement of their right to property granted under Article 300-A of the Constitution. They had been denied a no-objection certificate for transferring their property by a special tribunal. The Court held that they should be granted the certificate as it is their legal and constitutional rights.

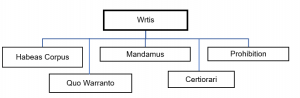

Types of Writ

The Supreme Court and the High Court have the power to issue 5 writs. These are:

-

Habeas Corpus

The term ‘Habeas Corpus’ is a Latin term which literally means ‘to have the body’. This writ is issued to relieve a person from unlawful detention. If a person is detained illegally and against his consent, he can file an application in the Supreme Court or High Court.

The scope of this writ was increased by the judiciary which was clarified in various cases like Sheela Barse v. State of Maharashtra that the doctrine of locus standi (right to approach the Court) is relaxed in habeas corpus cases. This means that if a detained person cannot plead for his release, his family, friends or any other person can file an application and approach either of the two courts for the same. Hence, this writ helps in protecting the liberty and freedom of citizens.

If the Court is satisfied with the application given, it can issue the writ of Habeas Corpus. Through the writ, the Court orders the presence of the person who had detained another person, ask them to provide a justifiable ground for the detention and orders a release of the detained person if it finds that the detention is not legally reasonable and justifiable. The detention is illegal if:

(1) The due procedure established by law was not followed for detaining a person or

(2) Detention was not in accordance with the law.

The application of this writ can be better understood by looking at the case of T.V. Eachara Varier vs Secretary To The Ministry Of Home, popularly known as the Rajan Case where a young boy, P Rajan was taken into police custody while he was studying in the college campus.

The principle of the college informed the father of the child about his arrest. This was done during the period of national emergency and for months, the whereabouts of the boy was not told to his family. In this case, the Court observed that P Rajan had been detained without any justification and issued the writ of Habeas Corpus for production of Rajan before itself.

There are certain circumstances where the writ of Habeas Corpus cannot be invoked. These include:

- If the person is detained as a result of a sentence or order given in a judicial proceeding.

- If the person is put into physical restraint under the law unless the law is declared unconstitutional.

- If the detained person has already been set free.

- If the person who detained another person does not come under the territorial jurisdiction of the Court in which the application has been filed.

- If the writ is filed during the emergency situation. However, it must be understood that the writ of habeas corpus would be maintainable only for the enforcement of fundamental rights granted in Articles 20 and 21 of the Indian Constitution even during the emergency situation.

2. Mandamus

The Latin term ‘Mandamus’ means ‘we command’. The writ is issued in the form of a command given by the judiciary which directs a constitutional, statutory or non-statutory body to perform a public duty which has been imposed upon it by the law. It can also be issued by a superior court commanding an inferior court to perform its duties.

This writ is also issued to prevent the authority from doing a particular act, which it is not legally entitled to do. The writ of Mandamus cannot be issued against a private individual who is not legally required to perform the public duty.

Thus if A is a police officer who is not performing his duty of registering a complaint brought to him by B, the Court can issue the writ of Mandamus, compelling him to register it. However, if A is not obligated by law to perform a duty, then the writ cannot be issued against him.

The writ of mandamus is issued on the following grounds:

- The petitioner has a legal right

- The legal right of the petitioner has been infringed

- The legal right has been infringed because of the non-performance of a legally required duty by a public authority or a private individual who is acting under public authority.

- The petitioner has demanded the performance of the duty but the public authority has refused to perform it.

The Courts have given importance to the rule of locus standi in cases involving this writ. However, in certain cases, public-spirited persons are allowed to apply for this writ on behalf of other people whose rights have been infringed. It is issued when there is an error of jurisdiction or error of law or violation of the principles of natural justice.

In the case of Bhopal Sugar Industries Ltd. V. income Tax Officer, the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal gave the respondent, an income tax officer certain direction for ascertaining the market value of sugarcane grown by the appellant in petitioners farms. However, the respondent did not follow these directions.

The Supreme Court held that refusal to carry out an order given by a superior tribunal in the exercise of its appellate jurisdiction violates the principles of justice and leads to chaos. Thus, the writ of Mandamus was issued directing the income tax officer to perform his duty in accordance with the order given by the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal.

However, when the act for which mandamus is sought has been completed or right of petitioner has lapsed or any other situation where issuing of the writ would be meaningless, the Court can refuse to issue it. It must also be mentioned that there are some situations where the writ is not granted. These include:

- It cannot lie against the following people:

- President or the governor of a state in their personal capacities.

- A practising Chief Justice

- The officials involved in various stages of conducting the elections to the parliament or state legislature.

- Private person or body

- If the duty to be performed is discretionary, not mandatory.

- For enforcement of a private contract between parties.

3. Certiorari

The Latin expression ‘Certiorari’ means ‘to certify’. It is issued in the form of a command by a superior court ordering an inferior court or any other inferior quasi-judicial body to transmit the records of a proceeding pending before it to the superior court. This is usually done in the following circumstances:

- When a superior court believes that the Inferior Court does not have jurisdiction to decide the matter.

- When the inferior courts violate the principles of natural justice while deciding the matter.

- When the inferior court decides on a matter procured by fraud.

- When the lower court makes a wrong decision because of an error of law which is apparent on the face of the record. This means that if the inferior court makes a decision based on a clear disregard of a statutory provision, the superior court can issue the writ of certiorari. However, if the decision is made because of errors in facts, then the writ is not applicable.

For example, if the High Court believes that the District Court which heads a case did not have monetary jurisdiction to decide upon the matter, and yet the district court has taken up the matter, the High Court can issue this writ and quash the district court’s order.

However, the superior court only has advisory jurisdiction (power of the court to give an opinion on an issue) in case the writ of Certiorari is issued. It does not exercise appellate jurisdiction (The power of the court to hear cases on appeal from the lower court) in these cases.

It must also be understood that the petition for Certiorari can only be made by the person who has been aggrieved. Thus, the doctrine of locus standi is very stringent in the matters of certiorari. For this reason, it is considered as a proceeding in personam.

The writ of certiorari is very important because it acts as a corrective remedy. For instance, in the case of Rafiq Khan v. State of U.P., the appellants were convicted under sections 352, 447 and 426 of the IPC by the Panchayati Adalat. They approached the Sub-Divisional Magistrate for the same and he modified the order given by the Panchayati Adalat. Allahabad high court held that the Sub-divisional Magistrate did not have a legal right to modify the order and quashed the modified order.

Before moving forward to discuss the other types of writs, we must understand the difference between Article 226 and 227 of the Indian Constitution. Very often petitions are filed under Article 226/227 as one petition. However, these two Articles are quite different in scope. While Article 226 gives the High Courts the power to issue writs, Article 227 talks about powers of general superintendents of High Courts over the Subordinate Courts.

This power allows them to keep a check on the subordinate courts and ensure that they do not make errors of jurisdiction. Hence, confusion regarding the writ of certiorari under both these Articles arise. While passing a writ of Certiorari under Article 226, the courts can only quash the order given by the subordinate court. Under Article 227 however, besides quashing the order, the High Court can also give appropriate directions to the inferior courts on the basis of the facts of the case and thus guide the courts.

4. Prohibition

The term ‘prohibition’ literally means ‘to forbid’. This writ is also known as ‘stay order’. It is issued by a superior court to prevent an inferior court or a quasi-judicial body from continuing its proceedings. It is issued in circumstances such as:

- When the inferior court or quasi-judicial body does not have jurisdiction to hear the case.

- When the inferior court or quasi-judicial body violates the principles of natural justice.

- When the inferior court or quasi-judicial body is not acting according to the provisions of the law.

The writ of prohibition, though similar to the writ of certiorari, is different in its nature. While the writ of certiorari is corrective in nature, the writ of prohibition is preventive in nature. This writ is issued by the superior court while the judicial proceeding is still going on in the inferior court or quasi-judicial body and before the final order is declared.

To understand this writ, one can refer to the case law East India Company Ltd. v. the Collector of Customs. In this case, the Supreme Court of India passed the writ of prohibition disallowing the respondent to proceed with the inquiry in an inferior tribunal on the ground that the proceedings were outside the tribunal’s jurisdiction.

5. Quo Warranto

The phrase ‘Quo Warranto’ means “ by what authority’.This writ restrains a person from acting in an office when he is not entitled to and has wrongfully usurped the position. The basic fundamental purpose of this writ is to ensure that an unlawful claimant does not take over a public office, as this can harm the public and takes away opportunities from those people who actually deserve to take over that office.

In the matters involving the writ of quo warranto, anybody can file the petition, even if the person who is filing the petition has not been personally aggrieved. When the writ of Quo Warranto is issued, certain essentials need to be fulfilled. These include:

- The office which has been wrongfully assumed is a public office, and not a private one.

- The public office has been created either by a statutory provision or the Constitution.

- The office is of a permanent nature and is not made for a temporary term.

- The person against whom the writ is to be issued is in possession of the office.

- The person against whom the writ is to be issued is one who has been disqualified from a public office, yet continues to possess it.

Thus if A is not qualified and has illegally taken possession of the office of a police officer, the Court can issue the writ of Quo Warranto and challenge this possession.

However, it must be observed that the Court has complete discretion in issuing this writ. Thus, if the court feels that issuing of this writ would not be beneficial, it has the discretion to not issue it. This can be understood with the help of the case.

In the case, of P.L. Lakhan Pal vs A.N.Ray the appointment of Justice A.N. Ray as Chief Justice of India was challenged because of lack of seniority. However, the court did not grant the writ of quo warranto because it would have been futile since the 3 other judges who were senior to him had resigned after his appointment and consequently, he had gained superiority over all other remaining judges in the Supreme Court.

Locus Standi

In Law, Locus Standi is the right of a person to bring legal action to the court. As per the strict approach of Locus Standi, the person has this right because he has sufficient connection to the case in hand. You can understand this concept better with the help of an illustration. If A’s right to equality has been violated, then because of locus standi, A can approach the Court of Law and bring a legal action to get remedy for this violation.

This practice of locus standi is very strict. Before the 1980’s only the affected party had the locus standi to file a case in a Court of law. However, this was found to lessen the scope of justice and a need for its change was observed during the post-emergency period. Consequently, the Supreme Court modified this strict practice of locus standi to tackle the problem of access to justice through various cases.

For instance, in case of Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union Of India, the petitioner initially faced a problem because of locus standi since it was an organisation not directly suffering because of bonded labourers working in stone quarries in Faridabad. The Court observed that there is no specific method of proceeding given in Article 32 and writ petition can be initiated in both formal and informal ways.

Thus, the question of locus standi was raised in this case and the court said that where a disadvantaged class does not have access to justice, the court can relax the strict principle of locus standi and allow a public-spirited citizen or group of citizens to approach the court on his behalf. Thereby, it allowed the petitioner to file the writ petition and allowing them to help the bonded labourers.

It must also be referred here that the Supreme Court has also been given epistolary jurisdiction which allows it to convert any informal petition made through letters, telegram etc, into a writ petition and hear the matter. For example, as a result of an open letter written by four eminent law professors, Vasudha Dhagamvar, Lotika Sarkar, Upendra Baxi, and Kelkar against the judgement given in Tuka Ram v. State of Maharashtra regarding the meaning of consent involved in sexual acts, the rape laws in India were amended.

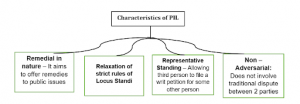

Public interest litigation – A dynamic approach

Public Interest Litigation (PIL) refers to litigation undertaken to redress public grievances and protect and promote the interest of the society at large. It allows any public-spirited person to approach the court and file a petition for a public cause, thus relaxing the strict rule of Locus Standi.

This can be better understood with the help of an illustration: A is a publicly spirited person who witnesses that an organisation is employing large no forced labourers, who due to poverty find it difficult to approach the court. PIL allows A to file a petition so that the right of these labourers can be upheld and they can escape the bonds of forced labour, even though he is not personally affected by such violation.

Before moving further, we must look at the characteristics of PIL. These are as follows:

Anybody can file a PIL in the Supreme Court under Article 32 of the Constitution and in the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution and the court of a magistrate under section 133 of CRPC. As discussed above, the PIL process can even be initiated by the court after it receives a letter, postcard, newspaper report or an email to it regarding a public issue.

These can be treated as a writ petition and the court can take action upon it, once it is satisfied that the letter is sent by the aggrieved person, a public-spirited person or a social action group dedicated to ensuring the enforcement of legal and Constitutional rights of disadvantaged people.

At times, the courts can also suo motu cognizance in such matters. This means that courts can by themselves initiate proceedings against a party. For instance, the suo motu cognizance by the court in matters of Delhi water pollution and directed the state to finalise in an action plan within 10 days.

Public Interest Litigation has gained a lot of importance. This is because:

- It helps in promoting the right to equality, protect the right to life and liberty and uphold the other fundamental rights of people who cannot represent themselves.

- By ensuring that the fundamental rights of all are protected, it allows promoting more human rights such as the right to education, medical care, housing, clean environment, speedy trial etc.

- It expands the scope of justice by allowing the courts to set up commissions to look into the matter and collect relevant evidence if a party is unable to do so because of economic backwardness.

- Because it is inexpensive in nature, it enables the court to provide a remedy to a greater number of people.

- It enables the court to ensure that the rights of minorities are protected.

- It also helps in raising public awareness about societal issues through increased media coverage.

Criticism of PIL

Throughout the years’ many criticisms have emerged with respect to PIL. Some of these are:

- The courts overstep their boundaries, particularly in the social and economic domain by laying down complex policies through PIL. Many people believe that other branches of the government are more equipped to formulate and analyse these policies. This is actively observed in cases related to pollution, sexual harassment, torture, management of CBI etc.

- Many people say that courts have taken undue advantage of the popularity that they have gained from PIL by expanding its powers and shielding itself from scrutiny.

- Some people also argue that courts have taken undue advantage of the inexpensive PIL process because of which multitude of cases come in. They say that courts spend a lot of time on frivolous cases which improves their popularity. For example, the court entertained a PIL to rename ‘Hindustan’.

- PIL have led to an increase in the burden of the workload of the superior courts, abuse of judicial power and increased the gap between the promises made and the actual reality.

- It is also being used by individuals for their private purposes, covered under the umbrella of public grievances to gain popularity.

- Moreover, PIL is being overused these days. As a result, its initial purpose of enforcing human rights of disadvantaged groups might get defeated entirely.

Abuse of PIL not to be allowed: Guidelines

It has been observed that the tool of PIL granted to the citizens is being abused. This is seen when frivolous cases are filed in the courts under the purview of PIL since it does not require heavy court fees. This leads to ignorance of important cases, which are many-a-times pushed to the background because of the frivolous cases. Thus, real justice is not achieved.

To overcome such abuse, certain guidelines have been laid down in the case of State of Uttaranchal v Balwant Singh in which the court imposed Rs. 1 Lakh on the respondents for filing a frivolous petition. The guidelines given by the court are as follows:

- The courts must encourage only genuine and bona fide PIL’s. All extraneous PIL applications must be discouraged. It must also be ensured that there is no motive of personal gain because of which a petitioner is filing this petition.

- All High Courts must devise their own procedures for dealing with PIL’s and formulate rules to encourage genuine PIL’s. The High Courts which have not formulated these rules must complete the formulation within 3 months and send a copy to the secretary-general of the Supreme Court.

- The court must, prima facie (on the face of it), verify the credentials of the petitioner before entertaining a PIL.

- Before entertaining the petition, the courts must prima facie be satisfied regarding the correctness of the contents of the PIL petition.

- The courts must ensure the PIL petition involves substantial public interest before deciding to entertain it.

- The courts must ensure that those PIL applications which involve larger public interest, are more grievous or are more urgent, are given priority over the other applications.

- The courts must impose exemplary costs if the applications filed is found to be frivolous.

Also, in the case of PN Kumar and another v Municipal Corporation of Delhi, the Supreme Court of India held that if a writ petition is pending before the High Court, a similar writ petition cannot be filed in the Supreme Court. In such cases, the parties can only move to the Supreme Court in appeal. This is because the Supreme Court is already highly burdened. Moreover, the High Court Judges are judges of eminence and have the necessary skills to look into such matters.

Besides these, the Courts have laid down the categories which will be entertained as PIL. These include:

- Bonded Labour matters,

- Neglected Children,

- Petition from jails complaining of harassment, death in jail and speedy trial,

- Petition against police for refusing to register a case, harassment for bribe, kidnapping, rape,

- Petition against the atrocities faced by women,

- Petition against harassment of people belonging to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes,

- Petitions pertaining to the environment,

- Petition from riot victims,

- Family Pensions.

These regulations help in limiting the abuse of the machinery of PIL and enable the court to only use PIL to achieve its actual purpose of ensuring justice.

Judicial Activism

Judicial activism is a dynamic process which allows the judiciary to depart from the existing laws and precedents to encourage the formulation of new social policies which fulfil the need of the hour.

Justice P.N. Bhagwati laid the foundation of this concept by allowing the citizens to initiate a PIL on the basis of a postcard or letter, in order to promote the socio-economic development of the society.

Though the concept of judicial activism has received criticism on account of overthrowing the principle of separation of powers and allowing the judges to rewrite policies as per their whims and fancies, its importance cannot be undermined. It allows the judiciary to correct the injustice when other branches of the government fail to do so, particularly in issues like protection of civil rights, political unfairness etc. It also allows judicial scrutiny into the working of hospitals and prisons which help in upholding basic human rights.

This can also be understood by looking at the case of Francis Coralie v. Union Territory of Delhi wherein the court interpreted the word ‘life’ in Article 21 (Right to life) and said it is not restricted to mere existence, but it also includes the right to live with human dignity and have the basic necessities which include adequate nutrition, clothing, shelter, freedom to move etc.

Power to award compensation under Art. 32

Article 32 has given a lot of power to the Supreme Court to protect the fundamental rights of the citizens of the country. In the case of Rudul Shah v. State of Bihar, the question of liability of the state to pay compensation regarding unlawful detention and violation of fundamental rights was raised.

It was held that Article 21 would not truly give justice if the powers of the court were limited to only passing orders for illegal detention. This is because monetary compensation encourages future prevention of such violation.

In the case of MC Mehta v. Union of India, the Supreme Court held that Article 32 of the Constitution does not limit the powers of the judiciary and allows it to provide an appropriate remedy, which can be given through providing compensation. The Court said that not enabling it to do so would render Article 32 futile.

The court held that the Supreme Court could entertain claims for damages in respect of violation of fundamental rights and has the power to award compensation in appropriate cases. It further explained that appropriate cases are those in which the infringement of fundamental rights is gross and such violation either effect a large number of people or is highly unjust and oppressive because of the economic and social backwardness of the person whose right has been violated.

There have been many case laws such as Bhim Singh v State of Jammu and Kashmir ( compensation given: Rs. 50000), Saheli v. Commissioner of police (Compensation given: Rs. 75000) etc where courts have awarded compensation under Article 32. In certain cases of violation of fundamental rights, the courts have also disregarded the sovereign immunity principle and made the state liable to pay compensation as a public law remedy.

The reason given for this is that if the state is unable to protect the fundamental rights which it has promised a citizen, it must compensate him/her for breaking the promise. Also, in many cases, such violation leads to permanent loss of income and thus the citizen must be compensated, Hence, by awarding compensation in such cases, courts ensure that true values of justice prevail in the nation and no entity takes undue advantage of its authority.

Corruption in Public Life and PIL

In recent years, incidences of corruption have reached their peak in India. Moreover, more often than not, the Central Bureau of Investigation and other agencies have failed to investigate these cases and bring justice to those wronged. PIL has, however, empowered the citizens of the country to bring to light the corrupt practices of the officials in the country. To understand this, we shall look at some case laws:

In the case of Common Cause, a registered society v. Union of India and others, the petitioners filed a writ petition against Captain Satish Sharma (who was at that time the Union minister of petroleum and natural gas) for his corrupt practices. The PIL was initiated on the basis of a news report which stated: “In Satish Sharma’s reign, petrol and patronage flow together”.

Following this, the court asked the Solicitor General to carry out an investigation regarding the same. The investigation found out that Captain Satish Charma corruptly used his discretionary quota of allocating petrol outlets and allotted them to various officials working with him. The court cancelled all of his 15 allotments and issued a show-cause notice to him.

Another case which must be referred to is Centre for Public Interest Litigation v. Union of India and Others. In this case, it was alleged that A. Raja, the former minister for Communications and IT, was following corruptive practices in issuing licenses to some favourable companies. Investigations carried out by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India, The Central Bureau of Investigation and Telecom Regulatory Authority of India observed that government had gained approximately 30 billion rupees in this allocation.

The Supreme Court cancelled all the 122 licences allotted by A. Raja. It further said that A Raja gave away important national assets and favoured some companies at the cost of public exchequer. It also held the allotment to be unconstitutional and arbitrary.

Effect of the existence of Alternative Remedy

While interpreting the Article 226 of the Constitution, the Courts have imposed a rule of restriction upon itself. This means that in cases where alternative remedies are available to the litigants, High Courts would not have jurisdiction to entertain the petitions under Article 226.

Such alternate remedy can be in the form of either:

- Normal forums following the hierarchy of Courts, or

- A suitable forum provided in a statutory provision, or

- A suitable forum existing otherwise.

This can be better understood by looking at the case law of U.P. State Bridge Corporation Ltd And Others. Vs. U.P. Rajya Setu Nigam S. Karamchari Sangh. In this case, the service of a workman was terminated since he was absent for ten continuous days on the grounds that he did not follow the order which asked for the same. The man filed a writ petition in the High Court but the petition was dismissed on the grounds that the case falls under Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 and should be taken up as an industrial dispute.

The limitation prescribed for seeking a remedy under Article 32

In the case of Trilokchand Motichand v. H.B. Munshi, the petitioners had filed a writ petition under Article 226 of the Constitution in the High Court to declare Section 21(4) of the Bombay Sales Tax Act, 1953 unconstitutional. This Article allowed the sales tax officer to forfeit a given sum if the condition on which it was given is not fulfilled. However, the court dismissed the petition on the ground that the petitioners had defrauded their customers.

However, The High Court struck this section down in 1967 stating that its violative of Article 19 (1) (f),(now omitted), of the Constitution of India. The petitioners pleaded that they must be given back the money as at the time of the petition, they were unaware of the grounds of the violation. However, the court held that mistake of law is not sufficient grounds to look into the case and that they had surpassed period of limitation.

In this context, The Supreme Court laid down certain limitations for seeking a remedy. These are:

- In case the petitioner has already approached the High Court under Article 226 of the

Constitution and the court have exercised its jurisdiction, the Supreme Court must refrain from acting under Article 32 of the Constitution.

In such cases, the Supreme Court must discourage the petitioners from filing a new petition and rather insist upon appeal.

- While inquiring into ‘belated and stale claim’, the court must give considerable notice to petitioners neglecting their own claims for a long-time period and also the neglect of the rights of other innocent people which happened because of such neglect. This means that the court introduced the concept of a period of limitation into seeking a remedy under Article 32. However, it was also held that an ultimate limit cannot be placed as the period of limitation would differ from case to case and the Limitation Act, 1963 would not apply to such petitions.

The distinction between Articles 32 and 226

|

Article 32 |

Article 226 |

|

It grants powers to the Supreme Court. |

It grants power to the High Courts in India. |

|

It is more restricted as it is invoked only for the enforcement of fundamental rights. |

It is invoked for enforcement of other rights as well. Hence, it has wider application. |

|

The power to issue writs given to the Supreme Court under this Article is mandatory. |

The power to issue writs given to the High Courts under this Article is discretionary. |

|

It is in itself a Fundamental Right under the Constitution of india. |

It is only a Constitutional right. |

|

It is suspended during Emergency, |

It is not suspended even during the Emergency. |

|

An order given under Article 32 supersedes an order given under Article 226 |

An order given under Article 226 falls behind an order given under Article 32 |

|

This Article has greater territorial jurisdiction. |

The territorial jurisdiction under Article 32 is limited to the state. |

Res Judicata

The principle of Res Judicata means that once a judgement has been pronounced by a court of competent jurisdiction on a given set of facts, it is binding between the parties unless the judgment given is modified or reversed in an appeal, revision or any other procedure applicable by law.

Under Article 32, the courts have limited their own jurisdiction by applying the concept of Res Judicata. This means that a person cannot apply for successive writ petitions with the same facts for the same cause of action. Also, a person cannot move to the Supreme Court with a new writ petition on the same facts if a judgement has been given under Article 226 by the High Court.

Illustration: A applies for a petition challenging the validity of tax assessment for a year and an order is given on the same in the High Court. As per the principle of Res Judicata, A cannot apply for new petition in another court.

However, there is an exception to the application of this principle under Article 32. This principle does not apply to cases of Habeas Corpus. Thus, in cases of illegal detention, a person can file a successive writ petition on the basis of new facts.

Restrictions on Fundamental Rights of Members of Armed Forces

Article 33 of the Indian Constitution allows the parliament to place restrictions and modify the fundamental rights granted to the members of armed forces, police forces, members of intelligent agencies and other such services.This has been provided so that the discipline, order and efficiency can be maintained in the army.

To understand this provision better, we should look at some case laws. In the case of Mohammad Zubair v. Union of India, the petitioner was a Muslim soldier who wanted to keep his beard as his faith did not allow him to cut it.

However, this was not allowed by the Air Force Policy and thus his plea was rejected by his commanding officer and he filed a writ petition in the Punjab and Haryana High Court in this regard.

The court held that this order was legal as even though Constitution recognised an individual’s right to faith, Article 33 allows the parliament to restrict this right as Uniformity of personal appearance is essential to ensure discipline in the armed forces, and thus the petition was dismissed.

However, Article 33 does not signify that the parliament can deny rights to the members of armed forces as per its whims and fancies. The wordings of Article 33 clearly say that the rights of such members can only be modified for two reasons which are :

(1) To ensure discipline and

(2) To ensure proper discharge of their duties.

This limitation was explained in the case of Union of India and others v. L.D. Balam Singh. The Court said that while Article 33 has allowed parliament to put restrictions on the fundamental rights of the members of the armed forces and forces responsible for maintaining public order, this does not mean that army personnel are denied the constitutional privileges.

Further in Lt. Col. Prithi Pal v. Union of India, the court also said that the process of placing limitations on the rights of members of the armed forces should not go so far that it creates a class of citizens not entitled to the benefits of the Constitution. It is the duty of the courts to strike a balance between ensuring discipline in armed forces personnel by modifying some of their rights so that their duty to maintain the rights of others citizens is not hampered, and providing them with enough rights so that they have access to civilised life.

Hence, clearly, Article 33 helps in ensuring not only discipline and efficiency in the armed forces but also allows maintenance of the basic rights of armed forces so that their undue advantage is not taken.

Martial law

The Indian Constitution does not define the term martial law. The term has been borrowed from English law and in its ordinary meaning simply signifies military rule. Imposition of Martial law signifies a situation where the authority to govern a place is taken over by the military forces of the country.

These authorities impose their own rules and regulations upon the civilians. Such rules are framed outside the ordinary laws which exist in the country. Martial Law is usually imposed in a very grave situation like war, failure of government etc and till date has not been imposed in India.

Restriction of Fundamental Rights while Martial Law is in force in the area

Article 34 of the Constitution of India impose restrictions of fundamental rights given to the citizens while martial law is in force in a particular area. It states that when martial law is imposed, the parliament can indemnify the men providing services to the state against any act done while such imposition, provided that the act done was for the purpose of maintaining and restoring order in that area. It also allows the parliament to validate any sentence passed under this period.

This indemnity provided cannot be challenged in the courts of India on the grounds that it violates a fundamental right. This is because, when martial law is imposed, the ordinary courts are suspended and all cases (including civil cases) are prosecuted in the military courts. Hence, the Supreme Court and the High Courts do not have any appellate jurisdiction over orders passed by the military courts in this situation.

Power to make laws regarding fundamental rights

Article 35 of the Indian Constitution prohibits the legislature from making laws regarding Article 32, Article 33 and Article 34 and the Constitution, It also prohibits the legislature to make laws providing for punishment given to anyone for violating any fundamental rights. Instead, It gives this power only to the parliament.

Conclusion

The Article 32 and Article 226 of the Constitution have allowed the courts to enlarge the access to justice and have revolutionized the idea of Constitutional jurisprudence. Judicial review has proved to be a very healthy trend which has made the Constitution a dynamic document, more suitable to the society today. Also, PIL and Judicial Activism have allowed the members of the society to help each other and offer justice to the disadvantaged. They have also allowed the judiciary to take a goal oriented approach while resolving cases.

Though the judiciary has been given vast powers under these Articles, it must be ensured that judiciary acts like the lighthouse and the destination itself. While passing orders it should also be ensured that judiciary works in a self- restrained manner and is not overstepping its boundaries.

Besides these, Article 33 of the Constitution has enabled the State to ensure that the people providing services to the state, i.e., those who are members of the armed forces, police forces etc are not falling behind on their service and using fundamental rights as an excuse, by enabling the parliament to restrict some of their fundamental rights. At the same it has also not given unlimited power to the parliament for the same.

Article 34, on the other hand, goes a long way in ensuring that the state can properly recover from grievous circumstances by allowing the imposition of martial law and putting restrictions on the fundamental rights of people.

References

- http://www.legalservicesindia.com/Article/1844/Public-Interest-Litigation—A-Critical-Evaluation.html

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/education/news/Principle-of-Res-Judicata/Articleshow/748399.cms

- http://www.legalservicesindia.com/Article/2570/Remedy-of-Compensation-under-Article-32.html

- http://www.legalservicesindia.com/Article/2019/Judicial-Activism-and-Judicial-Restraint.html

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/right-to-Constitutional-remedies/

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/writ/#Prohibition

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skill.

https://t.me/joinchat/J_0YrBa4IBSHdpuTfQO_sA

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications