This article is written by Adv. Dilpreet Kaur Kharbanda. It is an effort to delve into the aspects of Divorce by Mutual Consent under Section 13B of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. Along with analysing the case of Devinder Singh Narula v. Meenakshi Nangia, the cases before and after this judgment have also been looked into to understand the evolution of divorce under the Consent Theory of Divorce. Furthermore, the extraordinary power of the Supreme Court enshrined under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution and how this power has been used over the years has been tried to be condensed. It also includes a few suggestions and frequently asked questions related to Section 13 B and Article 142.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Black’s Law Dictionary (9th edition, 2009) defines Marriage as “the legal union of a couple as spouses”. This definition has undergone varied changes, adapting to the changing times and has even become gender-neutral as an outcome of the acceptance of same-sex couples in society. In the case of Tekait Amon Mohini Jemadai v. Basanti Kumar Singh (1901), the Calcutta High Court called the marriage under Hindu Law to be an indissoluble union of flesh with flesh and bone with bone. There has been a tussle between courts as to whether marriage is to be considered a sacrament or a contract. Different courts have had different opinions; some considered it solely pious and sacramental. In contrast, some of the courts settled on the stance of Hindu Marriage being a combination of both a sacrament and a civil contract.

The hidden aspect of Hindu Marriage, being a contract, brings forth the concept of divorce. According to Vedas and the Holy Scriptures, once two people enter into a holy matrimony, they are inseparable. Originally, in Vedas and Dharmashastras, no concept of divorce existed. But with the changing times and acceptance of marriage being more than just a religious practice and equally about a partnership and companionship between two people, the need for statutory provisions for divorce was felt. Thus, the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 came into existence that provided provisions dealing with Marriage as well as Divorce. In the original text of the act, only a few grounds of divorce were present under Section 13, but later, different grounds, as well as the concept of mutual divorce, were added in the form of Section 13 B.

Details of the case

Case Name: Devinder Singh Narula v. Meenakshi Nangia

Equivalent Citations: 2012 (8) SCC 580, 2012 AIR (SC) 2890, 2012 (7) JT 519, 2012 (7) SCALE 473

Court: Supreme Court of India

Bench: J. Altamas Kabir and J. Chelameswar

Appellant: Devinder Singh Narula

Respondent: Meenakshi Nangia

Date of Judgment: 22.08.2012

Legal Provisions Involved:

- Section 12, Section 13 B of Hindu Marriage Act, 1955,

- Article 142 of the Indian Constitution

Facts of Devinder Singh Narula vs. Meenakshi Nangia (2012)

- On 26.03.2011, marriage was solemnised between the Appellant and the Respondent.

- The Appellant filed a petition under Section 12 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (hereinafter referred to as HMA) on 01.06.2011 on the grounds of marriage being a nullity.

- During the pendency of the petition under Section 12 of HMA, 1955, the parties decided to go for mediation. Therein, the parties agreed to dissolve the marriage by filing a petition under Section 13 B of HMA, 1955, i.e., Divorce by Mutual Consent. The report of the mediator was submitted to the Mediation Centre of Tis Hazari Court, New Delhi.

- After the agreement, an application was put up on 15.10.2011, in the pending case under Section 12, that the parties would like to settle under Section 13 B and would file the petition on or before 15.04.2012.

- A Joint Petition by both the appellant and the respondent-wife was filed on 13.04.2012 under Section 13 B before the Additional District Judge, West Delhi.

- The court fixed the 2nd Motion to be heard on 15.10.2012.

- Aggrieved by the decision of the judge on fixing the date for the 2nd motion at a gap of 6 months, the parties filed the present appeal before the Supreme Court, praying for an exception from completing the cooling period of 6 months before filing the 2nd Motion.

Issues Raised

After perusing the facts and circumstances at hand, the Hon’ble Supreme settled on the issue of Whether the Cooling period of 6 months under Section 13 B of HMA be waived off.

Contentions of the parties

As the original petition filed was a divorce petition by a husband against his wife, thus, the title says, Devinder Singh v. Meenakshi. But, later a joint petition under Section 13 B was filed by both the husband and wife together. The present matter before the Supreme Court has been reached by way of an appeal. Thus, both the Appellant and the Respondent-wife made the same arguments and their arguments were countered by the Advocate of the state.

Arguments Advanced by the Appellant

The main arguments can be summarised in the following pointers:

- Both parties had been living separately since their marriage and even stopped cohabitation since the filing of the petition on 01.06.2011, i.e., almost a year and a half has elapsed since then. Furthermore, they don’t see each other living under the same roof even in the future, as the respondent-wife is living and working in Canada.

- A period of 18 months has elapsed from the date of filing the original petition (HMA No. 239 of 2011). This period of 6 months must be counted towards or set off against the 6-month cooling period requirement under Section 13B.

- Apart from this cooling period of 6 months, all other requirements of Section 13 B are being met by the parties.

- Parties relied on the case of Anil Kumar Jain v. Maya Jain (2009). They urged the court to invoke their power under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution and grant a decree of divorce on the ground of Irretrievable Breakdown of their marriage, as their marriage is just hanging by the formalities of the law and have no hope for their relationship to get better in future.

Arguments Advanced by the Respondent

The only argument the state made was that the cooling period of 6 months provided by the statutory provision should be strictly adhered to, otherwise, entertaining such prayer of waiving off the cooling period would cause confusion in the minds of the public and would be against the interest of the general public.

Judgment in Devinder Singh Narula vs. Meenakshi Nangia (2012)

Taking into consideration the arguments put forth by the parties and the state, the Hon’ble Supreme Court, using its power envisaged under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution, waived off the statutory cooling period of 6 months provided under Section 13 B(2). Court converted the petition pending under Section 12 of HMA, 1955 into a joint petition under Section 13 B, underlining that all the essential elements of Section 13 B(1) for granting divorce by mutual consent are met by the parties and the circumstances of the case are such that the marriage of the parties has completely broken down (irretrievable breakdown) and is hanging by a thread on mere account of the statutory requirement of cooling period of 6 months under Section 13 B(2). The Hon’ble Supreme Court allowed the appeal filed by the parties and granted divorce on mutual consent.

Rationale behind the Judgment

The court took into consideration that the parties have been living separately for over a period of one year since the date they filed the original petition and that already 4 months (a significant chunk of the cooling period) have elapsed and decided the remaining period of 2 months can be waived off. Moreover, the court exclaimed that the parties have never stayed together after their marriage and don’t seem to have any marital relations at all. There appears to be no hope for their relationship to change and for their marriage to be sustained.

Keeping in mind the legislative intent (saving the institution of marriage) of framing the said statutory provision and balancing it out with the exceptional circumstances of the case (doing complete justice to the parties), the court can exercise the power envisaged under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution.

The court relied on the judgment of Anil Kumar Jain and Kiran v. Sharad Dutt (1999). In the case of Anil Kumar Jain, the Hon’ble Supreme Court mentioned the three circumstances under which the court can exercise its extraordinary power under Article 142:

- Where the marriage is irretrievably broken

- Where one party withdraws consent in the case of divorce by mutual consent

- Where the statutory period under Section 13 B(2) has not been completed, still the court can grant divorce by mutual consent by waiving off the remaining period.

The Supreme Court, in the case of Kiran v. Sharad Dutt, while taking into consideration the period of time parties were living apart, reached a conclusion that waiting for another 6 months would mean just delaying the whole process and, thus, granting divorce on mutual consent.

Thus, the Supreme Court concluded, in exceptional circumstances, taking into consideration the facts and circumstances of the case, the court could exercise the right vested in them under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution and waive off the cooling period of 6 months.

Critical analysis of Devinder Singh Narula vs. Meenakshi Nangia (2012)

If one of the parties withdraws consent, can divorce still be granted in such a situation under Section 13B?

First, any party can withdraw their consent at any time before the divorce decree is passed. Hon’ble Supreme Court in Hitesh Bhatnagar v. Deepa Bhatnagar (2011), while pressing on the legislative intent, held that the period of 6 months under sub-section 2 of Section 13 B, is a cooling period where parties can rethink what they want, whether they want to go ahead with the divorce or not, etc. With regard to the consent, it was expanded by the Supreme Court in the case of Sureshta Devi v. Om Prakash (1991) that the mutual consent of the parties should continue till the decree of divorce is granted. However, the Hon’ble Supreme Court, in the case of Ashok Hurrah v. Rupa Bipin Zaveri (1997), was asked to reconsider the judgment of Sureshta Devi as it was too broad and not within the logical tenets of Section 13 B(2).

While discussing the Sureshta Devi Judgement, the Supreme Court dissected the facts of the case and looked into the decisions passed at all the stages of the case. The husband and wife filed a petition for mutual divorce. The second petition under section 13 B(2) was filed by the husband only and not by the wife. After 18 months had elapsed, the wife withdrew her consent. Considering the previous judgments passed by various high courts, the trial court decided that a decree of divorce could not be granted in such a situation. The matter went before a single judge of the High Court. The marriage was said to be irretrievably broken, and hence, the decree of divorce was said to be granted. Then, the matter was listed before the division bench of the High Court. The decision of the single bench was set aside.

When the matter went before the Supreme Court, after looking into all the circumstances and the allegations that husband and wife had made against each other, the fact that they were living separately for quite a long time and the marriage was just for namesake, to end the agony of both the partners and to do complete justice, Hon’ble Supreme Court used its extraordinary power envisaged under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution and passed decree of divorce on mutual consent under section 13B of the Hindu marriage Act, 1955.

So, even if the consent is withdrawn before the decree of divorce is granted, courts can still move forward with divorce on the ground of mutual consent, provided the marriage is irretrievably broken, and its substance is gone. It would be unfair for both parties to continue in such a relationship.

Furthermore, HMA does not provide for a set procedure as to how the petitions will be withdrawn. But the same can be deduced by relying on Section 21 of HMA. So, as per Section 21, High Court rules will apply to the withdrawal of petitions and will be governed by Order XXIII of the Code of Civil Procedure (Withdrawal and Adjustment of suits).

Can the statutory period of One year under Section 13 B(1) be waived off

There have been mixed opinions of the different High Courts about waiving off the period of 1 year before filing the petition for divorce on mutual consent.

Delhi High Court, in the case of Priya v. Sanjay Gaba (2004), taking into consideration the exceptional circumstances and that both the parties were completely willing to move ahead in their respective lives, held that the statutory period of one year could be waived.

Karnataka High Court, in the case of Sweety v. Sunil Kumar (2007), referred to the judgment of the Delhi High Court in the case of Pooja Gupta v. Nil (2003) and provided certain pointers to be kept in mind before waiving the statutory period of one year:

- the maturity and the comprehension of the spouses;

- absence of coercion/intimidation/undue influence;

- the duration of the marriage sought to be dissolved;

- absence of any possibility of reconciliation;

- lack of frivolity;

- lack of misrepresentation or concealment;

- the age of the spouses and the deleterious effect of continuation of a sterile marriage on the prospects of re-marriage of the parties.

But, Allahabad High Court, in the case of Arpit Garg v. Ayushi Jaiswal (2019) clearly denied the waiver of the statutory period of one year. The court observed that the period of 1 year of marriage before filing a petition for divorce on mutual consent is mandatory in nature. The intent of the legislature is absolutely clear and there is no ambiguity present. Hence, a literal interpretation of the statute needs to be done. Moreover, Section 13 B has to be read with Section 14, where the limitation of 1 year has been clearly provided.

Is the waiting period of 6 months under Section 13 B (2) mandatory

Over the years, different courts have had different opinions on whether the statutory period of 6 months is mandatory.

In 1986, the Andhra Pradesh High Court, in the case of Omprakash v. Nalini (1985), while quoting a Telugu Poet Vemana, “broken iron can be joined together but not broken hearts” called attention to why to wait for 6 months. The court waived the cooling period of 6 months. Similar judgments were passed by Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh High Courts as well.

In 2000, the Andhra Pradesh High Court, in the case of Hitesh Narendra Doshi v. Jesal Doshi (2000), observed that the provision for a waiting period of 6 months has been added with a specific purpose and hence cannot be changed. Correspondingly, the Punjab and Haryana High Court in 2006, in the case of Charanjit Singh Maan v. Neelam Maan (2006), held the statutory period provided is mandatory in nature. There is no ambiguity in Section 13 B(2), and hence, literal interpretation should be made, and a minimum period of 6 months must elapse before the 2nd Motion can be filed. A similar stance was taken by the Bombay High Court in the case of Savitri v. Principal Judge, Family Court, Nagpur (2008).

However, in the case of Manoj Kedia v. Anupama Kedia (2010), the Chhattisgarh High Court observed that the period of 6 months can be waived after enquiring about the circumstances of the case. If the marriage is irretrievably broken, there is no need to wait for 6 more months and a decree of divorce on mutual consent can be given.

The confusion on this point was finally settled by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Amardeep Singh v. Harveen Kaur (2017). Hon’ble Court held that the minimum period of 6 months can be relaxed in exceptional cases. The court clearly pointed out that where the court is encountered with a situation where the question of waiving off the cooling period is to be decided, the court should look for answers to a few questions:

- Whether a period of 18 months has already elapsed before even filing the 1st petition under Section 13 B(1)?

- Whether all the efforts have been made to reconcile between the partners as per Section 23(2) of HMA or in terms of Section 9 of the Family Courts Act?

- Whether the matters of alimony, child custody and similar related issues have been settled between the parties?

- Whether the waiting period prolong the parties’ agony?

If the answer to all these questions is in affirmation, courts can go ahead and waive the period of 6 months. The court held the request for a waiver can be made after 1 week of the filing of the 1st petition under Section 13 B (1).

Important provisions involved in Devinder Singh Narula vs. Meenakshi Nangia (2012)

Section 13 B of HMA,1955

Section 13 B was added by the 1976 Amendment Act. Before this, only Section 28 of the Special Marriage Act,1954 dealt with divorce by mutual consent. The major requirements of Section 13 B are discussed further.

The process of filing a petition for divorce by mutual consent is divided into 2 parts:

For filing the 1st Petition under Section 13 B (1) of HMA, 1955, the following requirements must be met:

- That the parties are living separately for 1 year or more before filing the petition. Living separately would include living in the same house but not fulfilling the marital duties towards each other.

- That they cannot live together anymore.

- That both parties want their marriage to get dissolved.

It is mandatory that the petition is to be jointly presented to the district court by the spouses only. Nobody other than the spouses can file a petition under Section 13B. The same has been held in the case of Ranjana Munshi v. Taral Munshi (1995).

2nd Petition/Motion under Section 13 B (2) can be moved by the parties after the expiration of 6 months and not later than 18 months from the date of filing of the 1st petition. The period of 18 months mentioned in the statute is an upper limit, but even after that, courts have the power to pass a decree of divorce. The same has been opined in the case of Santosh v. Virendra (1986).

If the parties do not withdraw the petition, the court can pass a decree for dissolution of marriage in the meantime. But before passing such a decree, the court must

- Hear both the parties, and

- Conduct a proper inquiry regarding the solemnisation of their marriage and check if the averments made in the petition by the parties are true or not.

If the courts are satisfied and all the statutory requirements are met, the marriage will be said to be dissolved from the date of the decree.

Evolution of Section 13 B

Section 13 B of the HMA, 1955 is based on the Consent Theory and Irretrievable Breakdown of the Marriage Theory of Divorce.

Consent theory is a much later developed theory of divorce. The basis of this theory is Contractual. If the parties have a right to enter into marriage with their consent, they have a similar right to dissolve their marriage. The major Criticism that this theory faced at the time of implementation in the form of Section 13 B, was that it will make taking Divorce way too easy. The entire institution of marriage will suffer. However, due to the safeguards provided in the provision, it cannot be said to be making divorce easy, rather, the stringent time periods provided for in the provision act as the necessary checks and balances.

Irretrievable Breakdown of Marriage Theory is somewhat a modern view of Divorce. This theory has been an ever-evolving process in our country. J. Salmond once said, “When the matrimonial relation has for that period ceased to exist de facto, it should, unless there are special reasons to the contrary, cease to exist de jure also”. In the 71st Law Commission Report, for the very first time, an irretrievable breakdown of marriage was recommended to be a ground of divorce under HMA, 1955. The Marriage Laws Amendment Bill, 2010 was also introduced in the parliament with an aim to amend both the Hindu Marriage Act and the Special Marriage Act. In 2013, it was even passed by the Rajya Sabha, but it never got passed from the Lok Sabha and thus, never saw the light of the day. Therefore, the irretrievable breakdown of marriage is still not a statutory ground of divorce under any of the marriage laws in India. The elements of Breakdown theory in relation to Hindu Law can be seen in two ways:

- Implied Breakdown

Section 13B provides an option to the parties to go for divorce through mutual consent, wherein parties feel there is nothing left in their marriage to make it survive.

Section 13(1A) (i) wherein if the decree of judicial separation has been passed and within that one year, parties have not cohabitated since then. This points towards the marriage being broken.

Section 13(1A) (ii), wherein there has been no restitution of conjugal rights even after the passing of a decree by the court for restitution, and one year or more time has elapsed. This also points towards marriage being a sinking ship.

But the courts have time and again cautioned to look into the circumstances carefully. In the case of Saroj Rani v. Sudarshan Kumar (1984), the Hon’ble Supreme held that where there is a decree of Restitution and its compliance has not been made. That will not straight away constitute a wrong under Section 23 of the Act. If the initiation of the case is fraudulent, let’s say a decree of Restitution is obtained with the only purpose of getting a divorce, then this is wrong. Both circumstances have to be integrated carefully. Where the intention is bad, that can be considered falling under Section 23 of the act.

- Judicial Recognition (Precedents)

In the case of Ashok Hurra v. Rupa Bipin Zaveri (1997), the Hon’ble Court observed that marriage, as per the facts of that particular case, was dead; there was no spark left, and hence divorce was granted.

Similarly, in the case of Romesh Chander v. Savitri (1995), Naveen Kohli v. Neelu Kohli (2006), Anil Kumar Jain v. Maya Jain, Hon’ble Supreme Court has time and again taken into consideration the fact that if the marriage has become emotionally and physically dead, it won’t be fair for the courts just to close their eyes, it wouldn’t fall within the ambit of ‘complete justice’. Thus, courts have allowed divorce on the ground that the marriage is irretrievably broken.

Hon’ble Supreme Court in Devinder Singh Case also took note of the marriage being irretrievably broken and that is why it used the power envisaged under Article 142 to waive off the cooling period.

With the passage of time, the interpretation of Section 13 B has changed. Courts have set precedents with reference to different factual situations.

Article 142 of the Indian Constitution

To understand the aspects of Article 142, we need to read the provision through and through. The power provided by the Article is wide enough that the court can use the same to pass any decree or order. The powers envisaged under the article are elastic to suit the needs of different situations. The exact word used is ‘complete justice’. Courts have time and again interpreted this term to realise the extent of the power. Hon’ble Supreme Court, Constitution Bench, in the case of Prem Chand Garg v. Excise Commissioner (1962) held that, that the order that the Supreme Court can pass under Article 142 should not violate the Fundamental Rights and, at the same time to do complete justice, should not be violative of the statutory provisions with regard to which order is passed. A similar stance was taken in the case of Supreme Court Bar Association v. Union of India (1998), where the court observed that until and unless the order or decree passed under Article 142 is not violating any fundamental right and is not against the public policy, it won’t be violating the provisions of the statute made by the Parliament, in the way of achieving ‘complete justice’.

Relevant case laws

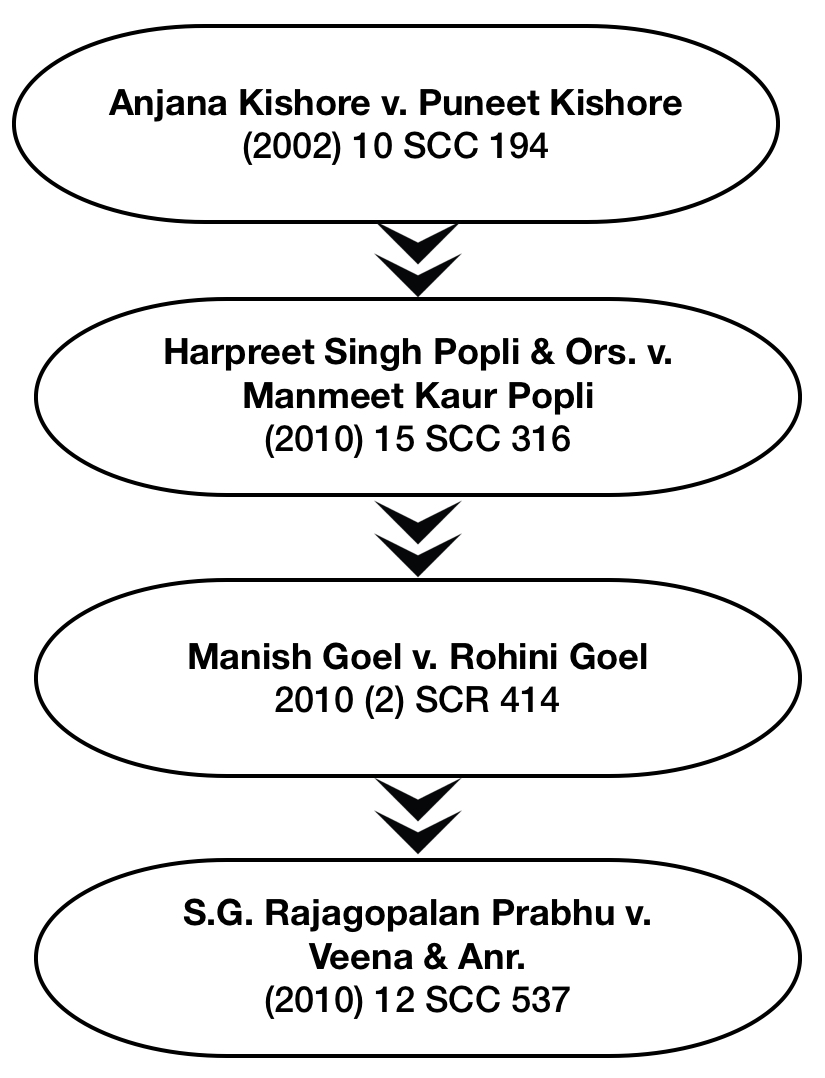

Understanding the judgments pronounced before Devinder Singh, gives us a wide idea as to how courts used to interpret the law in different circumstances and what different approaches have brought the courts to where they are in the present. Let’s understand these few judgments in chronological order.

Anjana Kishore v. Puneet Kishore (2002)

In the case of Anjana Kishore v. Puneet Kishore (2002), the Hon’ble Supreme Court invoked its extraordinary power under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution. It waived off the cooling period of 6 months provided under Section 13 B (2). Waving off the cooling period was said to be done with the sole motive of doing ‘complete justice’, but there were no specific circumstances mentioned that the court took into consideration and concluded for the marriage to be broken.

Harpreet Singh Popli & Ors. v. Manmeet Kaur Popli & Anr. (2010)

The next case that came forth is Harpreet Singh Popli & Ors. v. Manmeet Kaur Popli & Anr. (2010). The Hon’ble Supreme Court withdrew the petitions filed by the wife under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, and the divorce petition under HMA and granted divorce on mutual consent by waiving off the 6 months time period provided under Section 13 B.

However, the major difference between this case and the Anjana Kishore case is that this court has no direct reference to its powers under Article 142. Moreover, in Harpreet Singh Polpli, the basis of divorce was the compromise deed entered into by the parties where the husband settled to pay the wife a sum of ₹13.50 Lacs. The Supreme Court waived off the 6 months time period but without any reference as to the power under Article 142.

Manish Goel v. Rohini Goel (2010)

Another important case that waived the way to Devinder Singh Narula’s judgment is Manish Goel v. Rohini Goel (2010). Hon’ble Supreme Court dismissed the petition and did not invoke its powers under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution. Instead, the Hon’ble court stuck to the point of the motive of the legislature behind the framing of the statute. The court held, “In exercise of the power under Article 142, this court generally does not pass an order in contravention of or ignoring the statutory provisions. Not the power is exercised merely on sympathy”.

S G Rajagopalan Prabhu & Or. v. Veena & Anr. (2010)

Another important case that needs reference is S G Rajagopalan Prabhu & Or. v. Veena & Anr. (2010). On the basis of the compromise agreement entered into by the parties, the court allowed the petition for divorce by mutual consent. But, similar to the case of Harpreet Singh Popli, there was no direct reference to the use of extraordinary power under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution.

The loopholes present in each of the cases above, and the confusion that prevailed were put to rest by the Devinder Singh Narula Case. Further clarity on the subject came with two important judgments that are mentioned below:

In the case of Amardeep Singh, as discussed above, the Supreme Court provided certain considerations that the courts should keep in mind before waiving off the cooling period of 6 months. With regard to the power under Article 142, the Supreme Court clearly observed that the order passed by the court should not be in violation of the statutory provisions, especially in matters that are not present before the very court.

Shilpa Shailesh v. Varun Sreenivasan, (2023)

Hon’ble Supreme Court, in the case of Shilpa Shailesh v. Varun Sreenivasan (2023), observed and held in affirmative that the court can use its power under Article 142 in matters of divorce by mutual consent. The legislative intent of the cooling period of 6 months is not at all sidelined and is absolutely respected. But there are such exceptional circumstances where lingering on or giving time for reconciliation only exaggerates the pain and agony. In such cases, the procedure should be sidelined for a while for bigger public and personal interest. Only then would courts be able to do complete justice in the truest sense. At the same time, the court cautioned to follow the considerations laid down in the case of Amardeep Singh and Amit Kumar v. Suman Beniwal (2021).

Divorce by mutual consent under other laws

The concept of Divorce by Mutual Consent has, over time, made its place in different laws governing people of different religions.

Special Marriage Act, 1954

Section 28 of the Special Marriage Act deals with Divorce by Mutual Consent. This process and requirements of filing a petition under Section 28 are similar to that under HMA. But before filing the petition under Section 28, certain pointers need to be kept in mind:

- Parties must have married under the Special Marriage Act (inferred from Section 28(2)).

- Before filing the petition, it is advisable, as indicated in the case of Amardeep Singh, that parties should sort out all the disputes and issues so that there are no future litigations because of that. Furthermore, matters related to alimony, child custody, child maintenance, and education are often advised to be sorted out and decided upon.

After all these requirements are met, then:

The spouses can file a joint petition to the court. The court will make an inquiry into the circumstances and will record the statements of the parties. After that, an order of inquiry will be given by the court. A cooling period of 6 months will be provided if the parties want to reconcile. Parties have to move a 2nd petition after the elapse of a minimum of 6 months and a maximum of 18 months. Again, the court will make an inquiry into the averments made by the parties. If the court feels right, it will pass the decree of divorce on mutual grounds.

Parsi Law

Section 32 B of the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1934, provides for divorce by mutual consent. This provision was added by the 1988 amendment. The grounds and requirements for applying under this provision are exactly the same as under the Special Marriage Act and Hindu Marriage Act. There are just 2 differences:

- 1st is that parties must have married under the Parsi Law.

- 2nd being that there is no mandatory provision of a cooling period of 6 months between the two petitions.

Christian Law

Section 10 A of the Indian Divorce Act, 1869, provides for divorce by mutual consent. Provision was added by the 2001 Amendment. The grounds and requirements for applying under this provision are exactly the same as under the other laws. There are just 2 differences:

- 1st being, parties must have married under Christian Law.

- 2nd being, both the parties must have been living separately for a period of 2 years or more.

In the case of Reynold Rajamani v. Union of India (1982), the Hon’ble Supreme Court observed that where parties got married under Christian Law, they could not get their marriage annulled under Section 28 of the Special Marriage Act, 1954.

With regard to the period of 2 years, the Division Bench of Hon’ble Kerala High Court, in the case of Soumya Thomas v. Union of India (2010), has clearly held that this distinction from other laws is completely arbitrary and unconstitutional. To quote the exact words, “…..offends the mandate of equality and right to life under Arts.14 and 21 of the Constitution. Applying the doctrine of severability as has been held in the case of D.S. Nakara v. Union of India (1982), we are satisfied that we will be well within the power of this Court to read down such an unconstitutional provision, which is unrelated to the object sought to be achieved. The stipulation of two years can be severed and can be read down to one year to bring in conformity with the provisions of other laws to avoid the vice of unconstitutionality.”

Muslim Law

Muslim law does not, in any codified form, put forth provisions with regard to divorce by Mutual Consent. But, Khula and Mubarat forms of Divorce fall under the category of Divorce by Mutual Consent.

Khula is a type of divorce at the instance of the wife. Literally, ‘Khula’ means to draw off or put off. The history of Khula can be put into words: once, a woman went to Prophet Muhammad and said I can’t remain/stay with my husband anymore, and at the same time, I don’t even want to cheat Islam by staying out of marriage. I want my relations with the Husband to be severed. Prophet replied, “If you have decided so, are you ready to give away the garden to him, if you can, your marriage stands terminated.”

Privy Council in the case of Buzul-ul- Raheem v. Lateef-oon – Nissa (1861) held that divorce by Khula is a divorce by consent and at the instance of the wife, in which she gives or agrees to give consideration to the husband for releasing her from marriage ties.

Unlike Khula, Mubarat is the dissolution of marriage by mutual consent. Furthermore, there is no concept of consideration that is to be paid by the wife to the husband. Those who criticise the Islamic law of Divorce have put this type of divorce under the carpet.

Prophet Mohammad has said, “If a marriage can’t work, let it be dissolved.”

Both Shias and Sunnis recognise Mubarat as an acceptable form of divorce, and this type of divorce is irrevocable in nature.

Conclusion

The judgment of Devinder Singh Narula came at such a juncture where the courts were providing relief to the parties by simply waiving off the cooling period of 6 months under Section 13 B on the basis that their marriage was irretrievably broken. There is no anticipation of reconciliation between them, or the courts were specifically using their plenary powers under Article 142 to waive off the statutory period of 6 months. Before this judgment, there was no inter-relation defined between these two provisions by the court. So, Devinder Singh’s judgment condensed down the law and even opened further paths for the courts to delve into these particular provisions. The abovementioned judgments clearly show how much the legal horizons have widened over the last decade.

However, there is still a loophole in the entire process of divorce by mutual consent, and that is the absence of a specific provision providing for the irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a separate ground of divorce. Along with that, the ratio of Amardeep Singh should also be a part of the statute, wherein the time period of 6 months be clarified as discretionary and not mandatory in nature. There is no abnegating the fact that the Supreme Court has started giving relief by using its power under Article 142, but that makes just the Supreme Court a relief-giving authority. There is still no relief that the District and Family Courts can provide with regard to divorce by mutual consent. If all such divorce matters reach the Supreme Court, it will lead to overburdening the entire system.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

When was the concept of Divorce by Mutual Consent under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 introduced in India?

The concept of divorce by mutual consent was introduced in India by the Amendment of 1976 (Act 68 of 1976) in the form of Section 13 B.

Who can one file the petition for divorce by mutual consent under the Hindu Marriage Act 1955?

The petition can only be filed by the spouses. Petition cannot be moved by some other family member on behalf of the spouses. A joint petition has to be moved by the parties under Section 13 B (1) of HMA.

What is the purpose behind the cooling period of 6 months before filing the 2nd petition/2nd motion?

The legislative purpose behind the six-month cooling period is to give couples time to clear their headspace and rethink their decision to get a divorce. It is an effort towards protecting the institution of marriage and giving the partners an opportunity to reconcile.

Is the cooling period of 6 months provided under section 13 B(2) Mandatory or discretionary in nature?

There was a constant tussle between different High Courts as to whether this period of 6 months could be waived off or not. Finally, the Supreme Court in the case of settled the contention by observing that the period of 6 months provided under section 13 B(2) is discretionary in nature, and the courts can waive off this cooling period, taking into consideration the exceptional circumstances of the case where the marriage is irretrievably broken.

What is the power of the Supreme Court envisaged under Article 142 of the Indian Constitution?

Article 142 of the Indian Constitution provides extraordinary power to the Supreme Court, wherein it can pass any order or decree to do complete justice in any matter pending before it. This power under Article 142 has been used by the Supreme Court in various cases, stretching from divorce by mutual consent cases to Chandigarh Mayor Election matter to Compensation to victims in the Union Carbide case, and the list goes on.

References

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/44782477?read-now=1%3Fread-now%3D1&seq=1

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/cooling-off-period/

- https://clpr.org.in/blog/supriyo-and-the-fundamental-right-to-marry/#:~:text=The%20Indian%20Constitution%20does%20not,right%20to%20health%2C%20education%20etc.

- https://www.scobserver.in/journal/shilpa-sailesh-judgment-a-step-towards-no-fault-divorce/

- https://www.scobserver.in/reports/divorce-under-article-142-judgement-in-plain-english/

- https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2023/05/02/supreme-court-article-142-of-indian-constitution-and-irretrievable-breakdown-of-marriage/

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals, and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications