This article is written by Shaambhavi Bhansali.

Section 66 A of the Information Technology Act has irked many for its blind and disingenuous replication of the British Statute and has posed a big question on the democratic right of free speech on the internet in India. The alarming rate at which cases under this section have multiplied forces us to ponder whether we, as citizens, have to consult legal notes before posting a message online or sending an SMS? If not, how big a risk are we and the person who ‘Likes’ what we say? Can a society be called democratic if it were to criminalise opinions that are likely to cause mere annoyance, inconvenience, insult or ill will?

May 2014 saw the arrest of 5 students by the Bangalore Police Department for alleged circulation of anti-Modi messages on Whatsapp under Section 505 of Indian Penal Code and Section 66 A of the IT Act. So what did the offensive message really contain? According to a Bangalore Mirror report, “The morphed picture showed the final rites of Modi being performed, attended by L K Advani, Rajnath Singh, Sushma Swaraj, Baba Ramdev, Maneka Gandhi and Varun Gandhi. It had a caption: Na Jeet Paye Jhooton Ka Sardar — Ab Ki Baar Antim Sanskar (A false leader will never win, this time it’s final rites).” The arrest was made under the pretext of message being wrong, alarming and prone to terror.

In one such other case, K.V. Srinivasan, a businessman tweeted to his 16 followers saying that Karti Chidambaram, a politician and son of then Finance Minister P Chidambaram, had “amassed more wealth than Vadra”. Karti Chidambaram, predictably did not take the tweet in good humour and filed a case against Mr. Srinivasan under Section 66 A of the IT Act. The Police acted with unusual alacrity and arrested Mr. Srinivasan at 5:00 a.m. on the next morning. Interestingly, Senior politician and then Janata Party president Subramanian Swamy had made stronger corruption allegations against Karti Chidambaram twice in the same year as Ravi Srinivasan twitter case. But no action was taken against Mr Swamy.

In yet another baffling incident, 2 young girls were arrested and sent to 14 days judicial custody for posting and liking a status on facebook opposing the shutdown of Mumbai following demise of popular politician, Bal Thackrey. Yet again, the garb of Section 66 A was used to level charges for allegedly sending and liking a ‘grossly offensive’ and ‘menacing’ message through a communication device.

Can writing an honest opinion about government actions or a political entity be qualified as menacing in nature by prudent individuals and would such an action not be a violation of free speech as enshrined under our constitution? Sure, the message possibly caused annoyance to a miniscule section of society, but do the present cases even remotely fall under the reasonable restrictions on freedom of speech and expression? Can the police be given such expansive and discretionary powers to interpret the law and arbitrarily arrest a person for so much as liking an opinion?

SO WHAT DOES SECTION 66 A OF THE IT ACT REALLY SAY?

Section 66A of the IT (Amendment) Act, 2008 states:

“66A. Punishment for sending offensive messages through communication service, etc.,

Any person who sends, by means of a computer resource or a communication device,—

(a) any information that is grossly offensive or has menacing character;

(b) any information which he knows to be false, but for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred, or ill will, persistently by making use of such computer resource or a communication device,

(c) any electronic mail or electronic mail message for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience or to deceive or to mislead the addressee or recipient about the origin of such messages shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and with fine.

Explanation: For the purposes of this section, terms “electronic mail” and “electronic mail message” means a message or information created or transmitted or received on a computer, computer system, computer resource or communication device including attachments in text, images, audio, video and any other electronic record, which may be transmitted with the message.”

Meaning

Section 66 A basically lays down punishment for sending out “offensive” messages through a computer or any communication device including mobile phones and tablets. The punishment under this section can extend to a maximum of 3 years and fine.

India has over 220 million internet users, 100 million facebookers and about 33 million Twitter users. Given the rapid innovation and advent in technology, new free speech opportunities are increasingly being offered by social media. Now, due to the extreme broad and ambiguous wording of Section 66 A, there could be millions of situations where raising a political opinion or making an innocuous political joke on such platforms could lead to criminalisation and mar the precious democracy that India proudly enjoys. For instance, if you swear or abuse somebody, the swear words could be said to be grossly offensive, could also be said to be having menacing character and your act could come within the ambit of Section 66 A. Electronic morphing which shows a person depicted in a bad light could also be seen as an example of information being grossly offensive or having menacing character. Threatening somebody with consequences for his life may also be construed as information which is grossly offensive or menacing.

Thus, in absence of any yardstick or specific definition given under the law, the interpretation of this section is wholly dependent on the subjective discretion of the law-enforcement agencies who may have diverse views on the same subject matter. The question which arises then is – can law enforcers have so much interpretative license that it becomes an alibi for discretionary infringement upon civil rights?

IS SECTION 66 A VIOLATIVE OF FREEDOM OF SPEECH AND EXPRESSION?

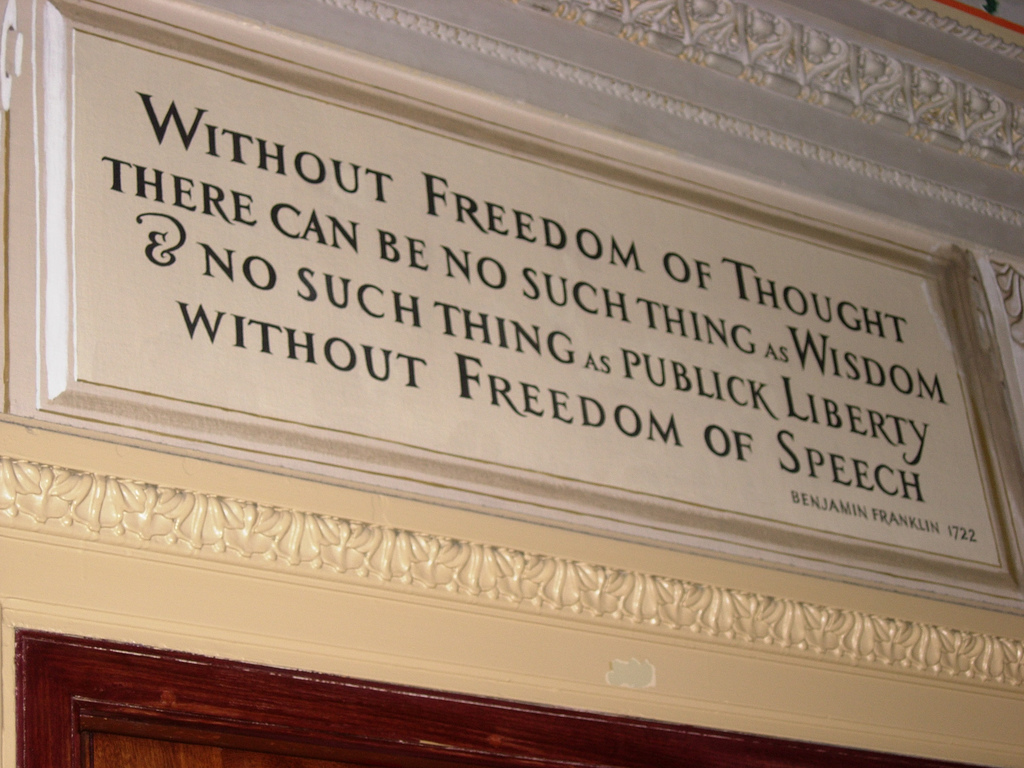

Understanding freedom of speech

Freedom of speech and expression means the right to express one’s conviction and opinions freely, by word of mouth, writing, printing, picture or electronic media[1] and includes freedom of propagation of ideas, their publication and circulation[2] and the right to answer the criticism leveled against such views[3]; the right to acquire and impart ideas and information about matters of common interest[4].

Article 19 (1) lays down right to freedom of speech and expression and comes with certain set of restrictions which enables the Legislature to impose restrictions upon freedom of speech and expression, on the following grounds-

- Sovereignty and Integrity of India ii. Security of the State iii. Friendly relations with foreign states iv. Public order v. Decency or Morality vi. Contempt of Court vii. Defamation viii. Incitement to an offence

Hence, even though as citizens they must abide by the orders of public officers, laws passed by the Legislature or judgments pronounced by the Courts, they must, at the same time, remain free as ‘the people’, to criticise the competence of or orders made by public officers, the policies involved in legislative measures and the merits of judicial decisions if they are to govern themselves. The Supreme Court in Union of India v. Assn. for Democratic Reforms[5] observed that: “One-sided information, disinformation, misinformation and non information, all equally create an uninformed citizenry which makes democracy a farce. Freedom of speech and expression includes right to impart and receive information which includes freedom to hold opinions”

So basically what these restrictions imply is that while it would be legitimate for the state to punish utterances which incite violence or have a tendency to create public disorder, it cannot suppress even a very strong criticism of the measure of Government or acts of public officials which has no such tendency.[6] Further, legitimate expression of views or ideas cannot be suppressed on the ground of intolerance others or of the existence of a ‘hostile audience.’[7] Thus, any restriction imposed upon the above freedom is prima facie unconstitutional, unless it can be justified under the limitation clause, i.e., Clause 2.

Analysis of Section 66 A with respect to Freedom of Speech

Section 66 A (a) makes sending out information which is grossly offensive and of menacing character punishable. Further, the section is silent as to who shall determine whether the information is of grossly offensive/menacing character.

Section 66A(b) has three main elements: (1) that the communication be known to be false; (2) that it be for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred or ill will; (3) that it be communicated persistently. The pivotal moot point here is that “annoyance”, “inconvenience”, “insult”, “ill will” and “hatred” are very different from “injury”, “danger, and “criminal intimidation” and the fact that they are put into one category is quite astonishing. More importantly what is to be understood is that it is very difficult to examine all publications on a common yardstick and what may be laughable allegation to progressive people could appear as heresy to a conservative or sensitive one[8].

Section 66 A (c) was inserted by the legislature as an anti-spam provision and makes an email sent “for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience or to deceive or to mislead the addressee or recipient about the origin of such messages” as a ground for punishment. For instance, if say due to some personal conflict of interest, a person writes a fiery email to his lawyer stating that he has failed his duties and that he should have never appointed him then, in all probability this email is going to cause annoyance to the lawyer. But is such annoyance really worthy of being punished? Will the inconvenience/ annoyance caused really fall under the reasonable restrictions of Article 19? Is such annoyance or inconvenience detrimental to the national security or public order of the country?

No democratic nation should want to curb internet freedom save in specific cases based on clear objectives. Thus, a penal law which is so vague and uncertain that it gives no notice to the accused as to what act or conduct would constitute the offence, or which imposes vicarious criminal liability, is unreasonable from substantive point of view.[9] The drafters of Section 66A(b) have equated known criminal offences in the real world with acts such as causing annoyance and inconvenience that can never constitute an offence in the real world and should not be offences in the virtual world. Therefore, the legislative restrictions on freedom of speech in Section 66A(b) cannot be considered as being necessary to achieve a legitimate objective. Section 66A should not be considered a ‘reasonable restriction’ within the meaning of Article 19 of the Constitution and must be struck down as an unconstitutional restriction on freedom of speech. If political speech, that is, criticism of politicians and exposure of corruption continues to be punished by arrest instead of being protected, India’s precious democracy and free society will be no more.[10]

SECTION 66 A – A CLOAK USED BY POLITICAL PARTIES TO SHUN CRITICISM?

The offence laid down under Section 66 A is cognisable and allows the Police to arrest and/or investigate the offending citizens without warrant. As a consequence, numerous citizens were arrested arbitrarily for putting objectionable content on the internet, where the objectionable content was more often than not merely an opinion dissenting some political opinion. To elucidate further, one may recall some glaring cases of such arrests –

- Sanjay Chaudhary for posting ‘objectionable comments and caricatures’ of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, Union Minister Kapil Sibal and Samajwadi Party president Mulayam Singh Yadav on his Facebook wall;

- Manoj Oswal for having caused ‘inconvenience’ to relatives of Nationalist Congress Party chief Sharad Pawar for allegations made on his website;

- Jadavpur University Professor Ambikesh Mahapatra for a political cartoon about West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee;

- two Air India employees, who were jailed for 12 days for allegedly defamatory remarks on Facebook and Orkut against a trade union leader and a politician, and

- Aseem Trivedi, accused of violation of the IT Act for drawing cartoons lampooning Parliament and the Constitution to depict its ineffectiveness.

Ironically, Section 66 A has never been used against a politician till date. One may then easily conclude that Section 66 A is used by political leaders and parties as a lethal tool to gag any voice that raises a question on their belief, policy or actions. What is perhaps shocking is the power that such political leaders exercise over the police authorities and how the otherwise infamous police acts with supreme agility and speed when it comes to simple harmless criticism made against such political bodies.

DOES THE LAW PROVIDE FOR A REMEDY AGAINST SUCH ARBITRARY ARRESTS?

Unfortunately, there is a lacuna in the regulatory framework for the effective investigation of cyber crimes and a general lack of awareness regarding cyber crimes on the part of police authorities. The absence of uniformity in cyber security control and enforcement practices puts the citizens at a greater risk of being subjected to undue police harassment.

A petition[11] has been filed before the Supreme Court for issuing guidelines to formulate an appropriate regulatory framework of rules, regulations and guidelines for the effective investigation of cyber crimes and to carry out awareness campaigns particularly for investigating agencies, intermediaries and the judiciary regarding the various forms of cyber crimes sought to be penalised.

However, as of today, the Petition remains pending before the Supreme Court and the arrests as shown above have not abated. Sadly, until some set guidelines are issued by the apex court, the netizens remain at the mercy of the police officers. Unbridled political interference in law enforcement is itself a burning issue and to argue that senior police officers who are often times controlled by political tyrants, will always succeed in resisting mob pressure or political diktats isn’t very persuasive.

WHAT HAS TRANSPIRED IN THE SUPREME COURT SO FAR?

Several PILs have been filed challenging the constitutionality of Section 66A of the IT Act. In a November 2012, the first PIL came to be filed by Shreya Singhal who submitted to the Supreme Court that Section 66A curbs freedom of speech and expression and violates Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution. The petition further contended that the expressions used in the Section are “vague” and “ambiguous” and that 66A is subject to “wanton abuse” in view of the subjective powers conferred on the police to interpret the law.

The PILs came to be first heard in 2014. The Union government defended the constitutionality of Section 66A stating that directives were issued to all state governments that arrests under Section 66 A can only be made with the approval of senior police officers.

The Petition was last heard on February 25, 2015 and the apex court after hearing the marathon of arguments put forth by the Petitioners and Centre has reserved its verdict on the constitutionality of the provisions of Section 66 A.

STRIKING A BALANCE

India is one of the largest democracies of the world and it is for this reason that reasonable restrictions on freedom of speech must be strictly construed. Section 66A of the amended Indian Information Technology Act, 2000 brings with it several evils which have created an uproar all over the country for being draconian in nature. Though the provisions of this section have been inspired by the noble objectives of protecting reputations and preventing misuse of networks, it failed miserably to achieve its objectives. The more narrowly focused the section, the better it is, since laws of libel and defamation already exist along with other laws pertaining to maintenance of public order.

HOW CAN SECTION 66 A BE USED MORE CONSTRUCTIVELY – THE WAY FORWARD

Are you a victim of hateful and graphically violent messages on the internet? Have your female friends often complained of incessant misogynist posts that go far beyond constructive criticism? Do your elderly relatives grieve over being duped into giving sensitive information which changed their bank balances?

Women face large amounts of sexist harassment, abuse and discrimination on the basis of their gender, rather than their opinions, thoughts or beliefs. Bloggers, Tweeters, journalists and Facebook users with prominent profiles face rape threats, violent pornographic vitriol, sexual harassment, accusations of promiscuity, and various forms of humiliation on a daily basis. This is a global problem with very little conversation or legal recourse surrounding it. In India, the first law to which a woman could logically recourse is Section 66A of the IT Act. In October 2014, Chinmayi Sripada, a Tamilian singer lodged a complaint with the Chennai Police stating that a few individuals were tweeting about her and her mother and making “casteist” and “vulgar” remarks. The Chennai police registered a case under Section 66A, and Tamil Nadu’s Prevention of Harassment of Women law and eventually arrested the two men under Section 66 A.

Another issue that Section 66 A aimed to achieve through its anti-spamming provision was a check on phishing activities that were unheard of couple of years back but recently have taken steep rise in India. The most common form of phishing is by emails pretending to be from a bank, where the sinister representative asks you to confirm your personal information/login detail for some made up reason like the bank is going to upgrade its server. Needless to say, the email contains a link to a fake website that looks exactly like the genuine site. The gullible customers, thinking that it is from the bank, enter the information asked for and send it into the hands of identity thieves. Since, the fraudster disguises himself as the real banker and uses the unique identifying feature of the bank or organisation say Logo, trademark etc. to deceive or to mislead the recipient about the origin of such email and thus, it clearly attracts the provisions of Section 66A IT Act, 2000.

Unfortunately, Section 66 A has caught the wrong spot light and the purpose for which the draftsmen amended the section has been washed away due to the rising number of arbitrary arrests. Section 66 A can be effectively used to deal with spam messages and curb phishing activities that are leading to increasing crime against thousands of innocent citizens. It can also be an effective deterrent for those putting offensive and threatening content on the internet. However, one may note that the poorly worded Section 66A is full of vague, undefined terminology, which means that its implementation will always be a subjective matter for those trying the case.

LEARNINGS

Even though Section 66 A has been widely criticised, you must remember that free speech was never intended to be an uncontrollable license to do anything inimical to the public welfare and the state shall always be entitled to punish those who abuse this freedom by utterances ‘tending to corrupt public morals, incitement to crime, or disturb public peace or utterances causing private injury’. Article 19 brings with it a fundamental right, the enjoyment of which is to be exercised with certain sense of responsibility.

Till the time Section 66A is either changed, modified, varied or amended, each of you must exercise due diligence before sending out any information on the Internet or voicing your opinion on social media, lest you may find yourself woken in the wee hours of the morning by our diligent cops.

[1] LIC v. Manubhai D. Shah, Prof., AIR 1993 SC 171 (para5): (1992) 3 SCC 637; People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India, (1997) a SCC 301 (para 19)

[2] Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras, AIR 1950 SC 124.

[3] LIC v. Manubhai D. Shah, Prof., AIR 1993 SC 171 (para5)

[4] Hamdard Dawakhana v. Union of India, AIR 1960 SC 554

[5] AIR 2001 Delhi 126

[6] Kedar Nath Singh V. State of Bihar, AIR 1962 SC 955

[7] Rangarajan s. v. Jagjivan Ram (1989) 2 SCJ 128

[8] BaragurRamachandrappa v. State of Karnataka, (2007) 5 SCC 11, (para 12)

[9] State of M.P. v. Baldeo Prasad, AIR 1961 SC 293(298)

[10] http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/an-unreasonable-restriction/article4432360.ece

[11] Dilipkumar Tulsidas Shah v. UoI [W.P.(C).No. 97 of 2013]

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications

What about people who use false name to say things? In internet it is possible. So no mention of it here?

Good balanced article. What about libel and slander. Offensive language used in S.66A does not fall under this?