The article is by Aviva Jogani, a 3rd Year BA LLB (Hons.) Student at Jindal Global Law School, Sonepat.

Introduction

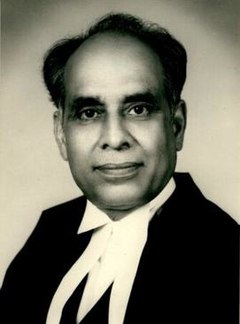

Sometimes, Indian Judicial system is alleged for corruptions but Justice Khanna was among those who lost his position as the chief justice only to seek justice for the Indian citizens. 3rd July 2018 marks the 106th birth anniversary of the Late Hon’ble Justice Hans Raj Khanna, the judge who is renowned for standing up for the fundamental rights of Indian citizens. Justice Khanna was the son of freedom fighter Srab Dyal Khanna who was a lawyer initially but later became the mayor of Amritsar.

Landmark judgment

He was well known for his judgment in the case of ADM Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla AIR 1976 SC 1207; Indian judiciary at that time was going through a dark phase. The Supreme court held that Article 21 includes the right to life and personal liberty against its unauthorized deprivation by the State. In case of suspension of Article 21 by emergency under Article 359, the court cannot question the authority or legality of such type of State decision. Article 358 is much broader than Article 359 as fundamental rights are suspended completely in the former but not necessarily in the later.

Justice Khanna was even terminated from his position of chief justice by late Prime Minister Indira Gandhi for his honest work ethic against the existing government at the time of emergency. This case is more commonly known as the Habeas Corpus Case. Habeas corpus is a Latin phrase which means that “you must have the body”. In the legal context, this means “a writ ordering a person under arrest to be brought before a court of law, so that the court may ascertain whether his/her detention is lawful”. In his dissent, Khanna said, “What is at stake is the rule of law …the question is whether the law speaking through the court can be absolutely silenced and rendered mute .”

Article 21 of the Constitution

Article 21 of the Constitution of India protects the right to life and liberty of every individual. This Article states,“No person shall be deprived of his/her life or personal liberty except according to the procedure established by law”. It is a well-settled fact that the procedure established by law under Article 21 must be “just, fair and reasonable”. To put it simply, this means that any procedure attempting to take away the life and personal liberty of an individual must follow the principles of natural justice that require an individual to be given an opportunity to be heard before any action can be taken against him/her. However, Article 359 of the Constitution of India had suspended the right to enforce this article where a Presidential proclamation of emergency is in operation. The issue that arose, in this case, was whether a writ of Habeas Corpus was enforceable by a person for challenging the grounds of his detention during such emergency.

The downfall of Indira Gandhi

This case falls in the backdrop of the elections of Indira Gandhi, the late Prime Minister of India, who was removed from her position for her indulgence in corrupt practices in 1975. This led to her being barred from contesting elections or holding office for a period of six years due to which she could not vote or speak in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Parliament, thereby rendering her dysfunctional and powerless. Threatened by the animosity of the opposition coupled with the fear of losing her seat as the Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi requested President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed to declare a state of emergency. At her behest, citing that India’s security was threatened by internal disturbances, he declared a state of emergency. Article 359 of the Constitution was invoked which deprived individuals of the right to enforce their fundamental rights. This was followed by a chain of unlawful detention of leaders of the opposition party without giving them an opportunity to be heard. Some of the leaders included Morarji Desai, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Jayaprakash Narayan and L.K. Advani. Consequently, several writ petitions were filed in various courts all over India.

Habeas Corpus Case

The case that followed was the famous Habeas Corpus Case, which was decided by a Five Judge Bench comprising CJI A.N. Ray, Justice Beg, Justice Chandrachud, Justice Bhagwati and Justice Khanna. Excluding Justice Khanna, the four others unabashedly and unflinchingly supported the Government in power concurring that no person can move the court by filing a writ of Habeas corpus questioning their grounds for detention during a proclamation of emergency. Justice Khanna stood alone in his dissent against Indira Gandhi. He maintained his view that no state has the power to deprive the person of his life and liberty without legal authority. He stated that:

“Article 21 cannot be considered to be the sole repository of the right to life and personal liberty of an individual. The right to life and liberty was not unknown at the time of constitution drafting; the principle that no one shall be deprived of his life and liberty without the authority of law was not a gift of the constitution. Thus, even in the absence of article 21, the state does not hold any power to deprive the citizens of their right to liberty. The power of the courts to issue a writ of habeas corpus is deemed to be one of the most important features of democratic states under the rule of law. The principle that no one shall be deprived of his life or liberty without the authority of law is derived from the notion that life and liberty are precious possessions of every individual”.

Justice Khanna in his autobiography Neither Roses Nor Thorns (2003) revealed that the night before the judgment he told his sister that even though his decision would cost him the seat of the Chief Justice of India, he had made up his mind. He vehemently dissented stating that the Judges were not there to only decide cases, but rather decide them as they deemed it to be correct. While it is highly regrettable that they could not generally concur, it is better for their autonomy to be kept up and maintained than be sacrificed for the wrong reasons. “A dispute in a Court of last resort appeals to the brooding spirit of the law, to the intelligence of a future day, when a later decision eventually may correct the error into which the dissenting Judge believed the court to have been betrayed”.

And so it did. In spite of being the senior-most judge, his junior Justice Beg superseded him to occupy the position of Chief Justice of India. All the judges in this case with the exception of Justice Khanna went on to become Chief Justice of India at some point of time. Although this was termed as the darkest hour in Indian democracy, which struck at the heart of the Constitution placing all the integrity and credibility of the Indian judiciary at stake, Justice Khanna stood as a guardian angel protecting his people at the cost of his own prospective success. Khushwant Singh, an Indian author and politician described Justice Khanna as “so clean a man that he makes angels look disheveled and dirty.” A few years later, Justice Bhagwati expressed regret by saying that he was completely wrong in making that judgment. If that case were to come to him today he would certainly agree with what Justice Khanna decided back then. He regrettably admitted that he had been swayed by the opinion of the other judges as he was a junior judge at that time. Since it was the first time such a case had come before him, he gave in to the majority views at that time.

This case became so groundbreaking that it was dissented not only in India but also internationally in several countries. The New York Times in its Article titled ‘Fading Hope in India’ wrote:

“In case, India is ever able to discover its way back to the freedom and democracy that were hallmarks of its initial eighteen years as an autonomous country, somebody will doubtlessly erect a landmark to Justice H R Khanna of the Supreme Court. It was Justice Khanna who stood up valiantly and eloquently for freedom of individuals by disagreeing with the Court’s decision of maintaining the privilege of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s Government to detain political rivals at their own will and without any court hearings. Indian democrats are probably going to recall infamously the four judges who dutifully overturned the decisions of a half‐dozen lower courts scattered over India which had disagreed to the decision of the Government. Thus, the privilege of habeas corpus could not be suspended despite the crisis that Mrs. Gandhi announced”.

Eventual consequence of the disharmony

This controversy eventually led to the 44th Constitutional Amendment in 1978, passed unanimously, which ensured that Article 21 could not be suspended even during a Presidential emergency. Justice Khanna was awarded the Padma Vibhushan, the second highest civilian honour given by the Government of India in 1999. Later, he also served as the law minister of India. Unlike the other judges of Supreme court, he was not ambitious and worked in favour of the rights of the common citizens of India. Rather he took decisions that he believed in, even if it required him to go against the government. He changed the picture of decision-making for Indian judges and became a role model for other Indian Judges. Moreover, he was internationally applauded for his decisions. His honesty, nobility, and virtues will not only continue to be deeply embedded in the heart of every Indian but also mark a touchstone for the entire Indian judiciary. He died at the age of 95 on 25th February 2008. He will always remain alive in the heart of the citizens for his noble work. We owe him the democracy that today guards our nation.

Reference

- V.N. Shukla, Constitution of India (2017), Professor Mahendra Pal Singh (revised), 13th Edition.

- Manish Chibber, ’35 yrs later, a former Chief Justice of India pleads guilty’, 2011, The Indian Express, available at<http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/35-yrs-later-a-former-chief-justice-of-india-pleads-guilty/847392/>.

- ‘Fading Hope in India’, 1976, Special to The New York Times, available at<https://www.nytimes.com/1976/04/30/archives/fading-hope-in-india.html>

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications