Written by Saloni Mathur, pursuing Certificate Course in Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code offered by Lawsikho as part of her coursework. Saloni completed her course in Company Secretary and is currently employed with S R Ashok and Associates Pvt. Ltd. as the Manager of Finance and Legal Department.

Introduction

How would you react when I term the history of Bankruptcy laws a mess?

When our Honourable Finance Minister Mr.ArunJaitley, did not fail to miss any opportunity to laud the journey of two years of IBC in one of his many speeches that marked a hopeful beginning of the New Year 2019, it might have left hundreds of people to ponder the structure of the new legal and regulatory regimethat governs the very foundation of the IBC.

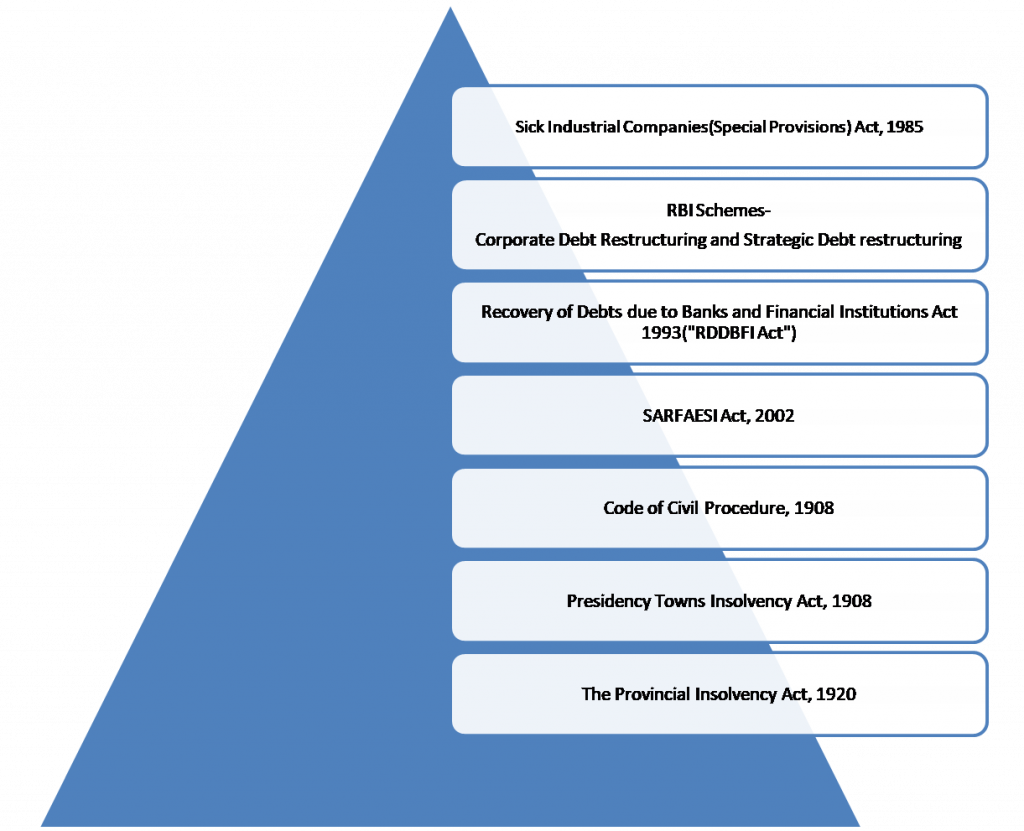

Insolvency Resolution Process is the talk of the town and most emerging issue in the history of the bankruptcy in India. This makes us reflect upon the already faded aura of the legal regime governing insolvency prior to the enactment of the Insolvency and the Bankruptcy code. There has been a reservoir of laws on insolvency prior to the IBC that came and went, and which apparently failed to resolve the complex bankruptcy issues. The Non-performing asset crisis surmounted, however no one-stop solution emerged. From Sick Industrial Companies (Special provisions), Act, 1985 to The Provincial Insolvency Act, 1920, The Presidency Towns Insolvency Act, 1909, The Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, and the SARFAESI Act, 2002 the journey has been quick and full of potholes that effusively started, however later failed to stick to the very purpose for which they were established.

This think piece is an attempt to comparatively analyse the laws on insolvency prior to and after the enactment of the IBC and to delve into the history of transition from various other Insolvency laws to the enactment of the IBC.

Governance prior to the Enactment of the IBC

Figure 1.1

Governance prior to the Enactment of the IBC

Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985

The Sick Industrial Companies (Special provisions) Act, 1985 defined the concept of the ‘sick company’ and a ‘potentially sick company’. The provisions under the Act defined the company as sick when there was a complete net worth erosion. The Act defined the sick company as any company that existed for at least five years and the accumulated losses exceeded or equalled net worth of any financial year.

The quasi-judicial bodies under the SICA were the Board for Industrial And Financial Reconstruction and the Appellate Authority for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction as defined under Section 3(b) and 3(a) of The Sick Industrial Companies (Special provisions) Act, 1985.[1] Section 15 of the SICA provided for reference to the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction, had the company become a sick industrial company within sixty days from the date of finalisation of the duly audited accounts of the company. The SICA failed due to its backward approach in dealing with the bankruptcy issues. There was a balance sheet approach to detect a sick unit rather than the prospective cash flow approach. It took a fairly long time for the net worth to erode, and the grave liquidity issues were never addressed.

The Companies (Second Amendment), Act 2002

The companies second Amendment Act, 2002 bought about amendments which directed to replace BIFR and AAIFR with NCLT and the NCLAT as the adjudicating authorities. Section 424A and 424L were introduced in the Indian Companies Act, 1956 to deal with revival, however they were never enforced.

Sick Industrial Companies (Special provisions) Repeal Act of 2003

The sick Industrial Companies (Special provisions) Repeal Act of 2003, [2] dissolved the appellate authority and the Board established under The Sick Industrial Companies (Special provisions) Act, 1985 i.e The BIFR and the AAIFR. However due to the delay in the constitution of the NCLT, SICA repeal Act was never notified.

The Recovery of Debts due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993(“RDDBFI Act”)

Under this Act, the Tiwari Committee constituted with the objective of solving the problem of recovery by the Banks and the Financial Institutions, proposed establishment of the specialized Tribunals, called the Debt Recovery Tribunals and the Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunals who would assist in unlocking the huge amount of public money and to move towards proper utilization of the funds for the development of the country.

The provisions of this Act did not apply to those Banks and Financial Institutions where the amount due is less than ten lakh rupees. Section 2(g) of the RDDBFI Act, 1993 defined debt which includes any amount claimed by the Bank and the Financial Institution during the course of any business activity whether secured or unsecured, assigned or payable under any decree or order. The RDDBFI Act, 1993 under section 19(19) also gave power to the Tribunals to issue certificate of recovery against the company registered under the Companies Act, 1956, to the recovery officers specially designated under this Act. The various modes of recovery as governed by Section 25 of the Act include:

- Attachment and sale of the movable and immovable property

- Arrest of the defendant

- Appointing a receiver for managing the properties of the defendant

The SARFAESI Act, 2002

The Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and enforcement of the Security Interest Act, 2002 was established with the purpose of the enforcement of the security interest created in favour of only the secured creditor, in accordance with the provisions of the Act. Section 13 of the SARFAESI Act, 2002 deals with the enforcement of Security Interest by the secured creditor after giving due notice to the parties for the discharge of their liabilities within sixty days of the date of notice failing which the secured creditor can take actions as stipulated under Section 13(4) of the Act. These include:

- Taking possession of the secured assets of the borrowers.

- Taking over the management of the business of the borrower

- Appoint any person to manage the secured assets of the borrower.

The major drawback of the SARFAESI Act, 2002 was there were no rights available to the unsecured creditors under this legal regime.

The CDR and SDR mechanisms

The corporate debt restructuring mechanism was first issued in 2001 for implementation by the banks. The CDR mechanism was only limited to the banks and the financial institutions that had an aggregate exposure not exceeding 10 crore rupees. The mechanism was a non-statutory voluntary system or agreement entered between the creditors and borrowers for restructuring of the debt.

Strategic Debt restructuring was announced by the RBI on June 8, 2015 and the main objective of the scheme was the change in the management of the company to deal with the stressed assets. The number of cases that were resolved by such schemes turned out to be few in number and the desired results could not be achieved.

The route to the IBC

The insolvency and the bankruptcy code enacted in May, 2016 was a more holistic approach to dealing with the stressed assets. The code is a unified force that clubs the relevant provisions on all the laws that deal with the bankruptcy. The code is more creditor friendly, while it seeks to promote the interests of all the stakeholders of the corporate debtor. It has been designed in such a way that it unites the provisions of the SARFAESI, The RDDBFI, theCode of the Civil Procedure etc

Comparative Analysis on the Laws of Insolvency prior and after the enactment of the IBC

| S.No | Basis of differentiation | SICA | RDDBFI | SARFAESI | Restructuring Mechanisms | IBC |

| 01. | Trigger Amount | 1.Company existed for at least 5years

2.Accumulated losses >= net worth for any financial year |

Default is Rs.ten lakh or more than ten lakh | Amount of Default as owed to a secured creditor | Aggregate exposure not exceeding ten crore rupees | Minimum default amount of Rs.1,00,000 to file an application. |

| 02. | Objective | Rehabilitation and revival of sick industrial units | Establishment of specialised Tribunals called the Debt recovery Tribunals and other Appellate Tribunals to recover money due to banks and financial institutions | Enforcement of security interest over the property of the borrower and establishment of asset reconstruction companies | Change in the existing terms and conditions of the debt. | Maximisation of the value of the assets |

| 03. | Adjudicating Authorities | BIFR and AAIFR | Debt Recovery Tribunals( DRT) and Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunals | Assistance in recovery of dues by Chief Metropolitan Magistrate and Chief District Magistrate. Any party aggrieved by the action of Bank or financial Institution may file appeal to Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal. | RBI Regulations and inter-se voluntary agreement between creditors | National Company Law Tribunal and National Company Law Appellate Tribunal |

| 04. | Time-line | 1-2 years for further investigation of sick companies | More than two years | 1-2 years | Ongoing process | Model time line prescribed for corporate Insolvency Resolution process post which company goes into liquidation. The period ranges between 180 to maximum 270 days |

| 05. | Types of creditors covered | Secured and unsecured | Secured and unsecured | Secured | secured | Operational as well as financial creditors which include the secured and the unsecured creditors |

| 06. | Pillars of the legal regime | The adjudicating authorities | The specialised Tribunals established under the Act | Public Auction and enforcement of the security interest | RBI regulations | The Insolvency and the Bankruptcy Board of India( IBBI), The Information Utilities, The National Company law Tribunal and the Insolvency Professionals |

Table 1.1

Status of the Laws on Insolvency after the Enactment of the IBC

Moratorium

It is needless to say that the Insolvency and the bankruptcy code has unified the law relating to the enforcement of the statutory rights of the creditors. It has acted as a means of consolidation of all the existing laws relating to the insolvency of the corporate entities and the individuals into a single transaction.

Section 14 of the Insolvency and the Bankruptcy code stipulates the moratorium provisions imposed on the corporate debtor once the corporate insolvency resolution process starts against the defaulting company. Section 14(1) of the IBC bars following activities against the corporate debtor:

- The institution of suits or any proceedings against the defaulting company including execution of any judgement, decree or order in the court of law, Tribunal or the Adjudicating Authority.

- Any Action to enforce any security interest against the corporate debtor under the SARFAESI Act, 2002.

Thus any proceeding pending under the various existing Insolvency laws comes to a halt during the corporate insolvency resolution process of the companies. However there have been rulings where the Honourable High Court and the Supreme Court have prosecuted on any proceedings during the moratorium, and which have apparently been kept out of the purview of the moratorium.

No jurisdiction of civil courts under the code

Further section 63 of the Code stipulates that the civil court shall not have any jurisdiction to entertain any suit or proceedings in respect of any matter on which the NCLT has jurisdiction.

Choice of liquidation under the IBC

Once the company is under Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process, the existing laws on insolvency have almost no interplay. If the resolution plan submitted by various resolution applicants are accepted, the company has to follow it and all previous applications filed under existing insolvency laws are back to square one.

If no resolution plan is approved, the company automatically goes into liquidation. The creditors under Section 52 of the Code are given a choice of pursuing liquidation on their own or as a part of collective liquidation proceedings. If the existing SARFAESI applications are revived after CIRP, they have a later priority of payment as compared to Secured financial creditors under the normal ‘waterfall mechanism’ prescribed under Section 53 of the IBC.

Conclusion

One can aptly say that the Laws on Insolvency in India have been a complete conundrum. There has been a rise and fall of an insolvency regime, where each came to replicate the other, hardly bringing anything new with them. The IBC came as a one-stop solution that followed a prospective cash flow approach having sturdy pillars for its support, surpassing the existing insolvency regime.

The Code can more aptly be defined as a ‘Unified mechanism’ covering the bright sides of every failed Insolvency regime’. The model time line, the role of the adjudicating authorities, the IBBI, and the balancing approach with which the code has established itself, has really been a landmark moment.

Further if one analyses the status of all the existing Insolvency laws after the enactment of IBC, there seems almost a lost connection. All prior regimes started with a good energy, however failed to maintain the cohesiveness. It is and hopefully shall only be the IBC to bring a much needed reform.

Reference

[1]https://indiacode.nic.in/admin/view-casepdf?type=repealed&id=AC_CEN_2_2_00031_198601_1517807326263

[2]http://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/The%20Sick%20Industrial%20Companies%20%28Special%20Provisions%29%20Repeal%20Act%2C%202003.pdf

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications