This article is written by Sanat Prem, from O.P Jindal Global Law School.

Table of Contents

Introduction

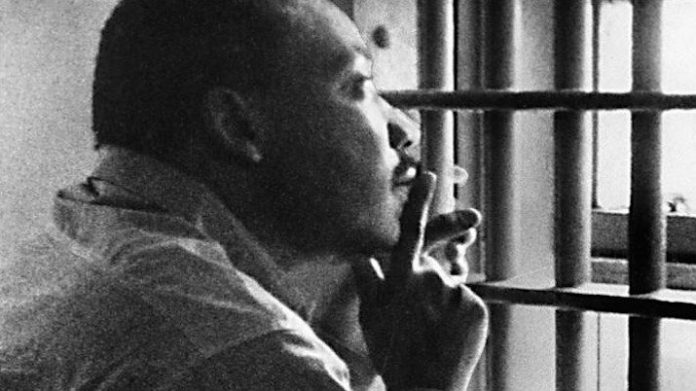

Martin Luther King once said: “It is not possible to be in favor of justice for some people and not be in favor of justice for all people.” It was justice for all that King was out to fight against. On 12th April, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested for breaking, what he termed as an “unjust” law – as he carried out demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama. He was kept in custody for twenty-four-hours without being allowed to exercise his constitutional right to contact a lawyer.

King came across a letter published by eight white religious leaders of the South in a prominent Birmingham newspaper, who termed these demonstrations as “unwise”; an indirect threat. Letter From Birmingham Jail is King’s response to these threats and accusations. In the six-page letter, his main theme revolves around his duty to fight for justice and fight against “unjust” laws.

Analysis through natural law: Thomas Aquinas

King argues about a moral responsibility to stand up against “unjust” laws. Man-made codes are just laws only if intertwined with moral law. According to a natural law perspective, no rule is law unless it is morally permissible. Moral validity is a necessary condition for legal validity and law must satisfy the demands of morality. I seek to infer King’s letter through a lens of natural law and the theory of Thomas Aquinas, whom King mentioned in his Letter. I would also briefly discuss the natural law perspective of Ronald Dworkin. Before delving into the jurisprudential aspect of King’s Letter, I would elaborate on Thomas Aquinas and his theory on both Natural and Eternal Law and then seek to connect the same with the text of Letter From Birmingham Jail.

Martin Luther King addresses the concern of the white religious leaders by acknowledging their concern of Blacks breaking the law as means of protest and disobedience. To explain his actions and that of his fellow-community members, King uses Thomas Aquinas’ theory of natural law. He addresses the issue by first providing a distinction between “just” and “unjust” laws and poses the question; “How does one determine when a law is just or unjust?”. The answer for King, while quoting Aquinas, depends on the connection of the law in question with that of moral law or the law of God. Like Aquinas, King attaches an eternal and divine aspect to the law governing humanity. He claims that the distinction is based on the fact that the law in question does not have a necessary moral connotation to it. Quoting Aquinas, King writes – “An unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal and natural law.” King’s reliance on natural law is evident in his letter.

Those who analyse his letter today seldom ever mention his brief but effective use of the natural law theory within his letter. Aquinas, in his work Treatise on Law, considers law to be intrinsically linked to reason that directs human activity towards some end, goal or purpose; a sense of ultimate fulfilment or contentment. Law is not only restricted to recommendations or suggestions, but it is meant to bind and command members of society to shape their actions in a certain way. This is where Aquinas brings the point of eternal law and the idea of God – a divine power. He poses the question that if God is the reason for all life, activity, development and creator of the community, does He not have the highest degree of authority? Is He not the lawmaker and lawgiver? It is through Eternal Law that divine intellect designs and commands all creatures to a common end. Thus, in Aquinas’ view, when humans are acting for the betterment of humankind, they are simply observing the eternal law liberally; they are not making law, but merely discovering it. This law is further ratified to satisfy or suit the nature of humans; thus leading us to the idea of natural law (lex naturalis).

Aquinas argued that human dictums can be, and predominantly are, in contradiction to the “human good” – and therefore unjust either by end, author or in formation. A law designed to enhance personal growth at the expense of others in the community is the first mode of legal injustice, according to the scheme presented by Aquinas. King kept in mind the Jim Crow laws when writing about legal injustice and unjust laws. Jim Crow laws comprised of state and local laws that enforced racial segregation in the Southern states of the U.S.

These laws were in force till 1965 – well in force when this letter was written by King. An illustration of Jim Crow law provision is as follows – “It shall be unlawful for a negro and white person to play together or in company with each other at any game of pool or billiards.” This law was effective in Alabama, thus very prevalent in Birmingham which is where King wrote this letter from and where his movement was out in full force. For King, the laws are unjust because it degrades human personality and gives the “segregator” a false sense of superiority over the “segregated.” This is intertwined with Aquinas’ idea mentioned earlier about personal growth at the expense of others being the first mode of injustice. The law itself is morally wrong and sinful.

In a nutshell, Aquinas believed that natural law is merely a sharing or participation of the eternal law. He insists it is not different from the highest authority of law that exists in the mind of God: “the natural law is nothing else than the rational creature’s participation in the eternal law.” Whenever humans engage in some form of “practical reasoning” about what is possibly noble and act in accordance with some sort of rational determination, natural law is practiced or observed. The first and most fundamental principle of natural law, quoting Aquinas, was: “anything good is to be pursued and evil is to be avoided in all human acts.”

Natural law involves deciphering as to what is best for humans by nature; thus, leading us towards man-made laws. Aquinas believed that the portion of eternal law that deals with humankind cannot be completely grasped by human intellect; it is because of this that we must make our own laws through the help of the ever-present eternal law. We do this by deriving general norms and principles acceptable and applicable in society. In essence, Aquinas looks at law with four basic characteristics:

(i) an order of practical reason;

(ii) directed towards a common goal;

(iii) made by someone who cares for the community; and

(iv) to be propagated.

For King, the final and most obvious mode of injustice was “a law just on face value but unjust in its application.” He illustrated this through a law that required permits for marches; thereby clarifying that there was nothing wrong with the law itself. King, however, highlighted the fact his community was always denied permits for a civil rights protest was unjust in itself. The law was merely an impediment operated to stop the Black community from carrying out mass demonstrations. Thus, through this illustration he applied Aquinas’ theory (and St. Augustine’s theory) that “unjust laws are no laws at all.” King believed that these acts of civil disobedience must not be condemned and that it has been prevalent since time immemorial.

Aquinas on civil disobedience

A discussion of Aquinas’ theory on civil disobedience is particularly useful in the discourse of Martin Luther King and the movement he led. Thomas Aquinas described obedience as a virtue under normal circumstances. In his word – “Inferiors are obliged by the order of natural and divine law to obey their superiors”. He, however, also considers disobedience in some situations other than “normality” as a virtue – two of the most common being disobedience against unjust laws and the overthrowing of tyrants. Aquinas tries to distinguish the two situations; as disobeying unjust laws would naturally mean disobeying the tyrant who imposes it. It is, however, fundamentally different from overthrowing the tyrant – in this case the tyrants being the “whites”. Martin Luther King simply meant to disobey the aforementioned Jim Crow laws, without necessarily implying an overthrow of the government. Therefore, any question of disobeying and overthrowing being the same are futile; fundamentally, they are completely different.

It is evident in Aquinas’ work that he condemned rebellion as a “mortal sin”, and some point this came out as a contradiction, given his unwavering stand on disobeying unjust laws. He defines rebellion as an act “contrary to both justice and the common good.” Disobedience of unjust laws are not considered to be contrary to justice and/or the common good; in fact, they meant to uphold these values. It is because of one’s belief in justice and the common good that they resort to rebellion when these values are violated. Hence, the act of disobedience is not an act of rebellion. Disobedience need not necessarily be “rebellious” in nature.

Role of the church- thoughts of Martin Luther King & Aquinas

Martin Luther King also expressed his disappointment with the role of the Church, or the lack of it, during this time of turmoil. King expected the white ministers, priests and rabbis of the South to be allies of the movement. To his disappointment, however, they turned out to be their most fierce opponents, refusing to comprehend the purpose of the movement. The silence of the Church was the most displeasing part for King. He condemned how the Church dismissed the struggle as a “social movement” which had nothing to do with the Gospel. King explains how the Church was once a powerful institution that not only upheld ideas and principles of popular opinion, but also transformed the morals of society that were intertwined with the popular opinions of that time. King illustrates how the Church was powerful enough to bring an end to evils such as infanticide and gladiatorial contests in ancient Rome. Now, however, he brands the Church as a “weak” and “ineffectual” voice; a supporter of maintaining status quo in society rather than bringing about a change. He penned how he hoped the Church regains its earlier authority.

While criticising the Church for its lack of support, Martin Luther King, again, although indirectly, refers to Aquinas and his word on spiritual authorities, i.e. the Church. Aquinas mentioned how we must obey the secular power rather than spiritual power when concerned with “civil welfare” or the “common good”; as long as extreme situations, such as the implementation of unjust laws, are not encountered. The moment we are faced with unjust laws the sword can be “unsheathed at the Church’s bidding”, in Aquinas’ words. Spiritual authorities are the sole interpreters of divine law. The Church keeps the conscience of the state in check and can help people judge for themselves whether the law is just or unjust and whether obedience is a prerequisite. The Church instils some sort of moral conscience for secular authorities should they resort to tyrannical deeds; and this is where a link can be drawn between Aquinas’ thoughts the Church and Martin Luther King’s criticism of the Church during this period of upheaval.

Caution while observing civil disobedience

Aquinas advises caution even in disobedience. According to him, unjust laws that force the general public to act contrary to the standard of natural law justifies the use of disobedience; as long as it does not result in “scandal” or “civil unrest”. Aquinas believed that in certain situations it may be wise to suffer injustice so as to not disrupt “public order.” It is believed that Aquinas accepted that the good of individuals lay secured in imperfect but secure order rather in a broken, unstable and scandalised community. King also borrowed a lot from a leading figure in Christian thought and teaching in early 5th A.D. – St. Augustine. Unlike Aquinas, Augustine did not subscribe to any “divine right.” Although, like Aquinas, he did maintain that “An unjust law is no law at all.” Augustine was also a man of peace, and spoke for unrest when a grave wrong required cessation, which is somewhat linked with Aquinas.

King’s stand on civil disobedience is not clear given some of his contradictory statements in various parts of the letter. For example, he provides an illustration by elaborating on just and unjust laws – “How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?”. To this he answers that there is a moral responsibility to obey just laws and disobey unjust laws. Later on, he slightly contradicts himself by stating – “In no sense do I advocate evading or defying the law, as would the rabid segregationists. That would lead to anarchy.” This is the dilemma that civil disobedience advocates have not completely grasped.

The perspective of Ronald Dworkin

Another lens through which we can examine the Letter is through theorist Ronald Dworkin and his take on civil disobedience. Dworkin recognizes that disobedience is morally justified, but rejects those who only consider the moral justification and turn a blind eye to the legal justification. To give an illustration of what this means, Erwin Griswold, a former Attorney General of the U.S., once said – “It is the essence of law that it is equally applied to all, that it binds all alike, irrespective of personal motive. For this reason, one who contemplates civil disobedience out of moral conviction should not be surprised and must not be bitter if a criminal conviction ensues. Organised society cannot endure on any other basis.”

According to Dworkin, the motives of the “dissenter” practicing civil disobedience must be considered. Leniency or inclination towards a party must depend on whether the law in question is morally right or not. For him, the civil rights laws clearly exemplify that Negroes, as individuals, have a right for not being segregated and discriminated against. If this carries on, we violate the moral rights for which humanity stands and which is confirmed by law. The leniency point advocated above can only go this far; and this seems to be in line with King’s line of thought on civil disobedience.

Conclusion

Martin Luther King Jr’s. goal of a utopian society was not achieved before his assassination in Memphis in 1968, and practically, may never be achieved. He believed that an alternate social order was attainable and desirable and thus propagated for a society that respected individual freedom but simultaneously recognised the need for a state to keep a check and regulate that freedom. A lot of King’s beliefs were nurtured during his childhood and his belief in a personal God. Historians today consider the two greatest influences on King’s thought and action to be:

(i) the biblical inheritance of the story of Christ; and

(ii) the black southern Baptist church heritage into which King was born.

The description and condemnation of the segregation laws as “morally wrong and sinful” comes from the theological framework that King put his faith in. His justification of civil disobedience comes from the teaching and understanding of the tradition of natural law philosophy. King was once asked if the protesters of his community offended God when they broke the law and ate lunch at the counter, or refused to give up a seat to white person in the bus, as prescribed by law? His response was simply: “Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality.” What King did was successfully and thoughtfully apply Aquinas’ third observation on unjust laws – which was that humans are not obligated to human laws if those laws bring injury and loss of character, destroying human dignity; they oppress the poor and humble. Oppressive laws, for Aquinas, were acts of violence and provocation and he maintained that no one must feel guilty about disobeying an unjust law.

Connecting these thoughts with the Letter, in my opinion, it is safe to assume that Martin Luther King Jr. firmly believed in the work of Thomas Aquinas; he was indeed a “Thomist”. Martin Luther King must be remembered as a Christian pastor who, for the best interests of his community and his nation, fought against injustice by appealing to laws higher than those of the state while compelling others to thoughtfully engage with the principles of a just and fair political and social order.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications