In this blog post, Srishti Khindaria, a student of Amity Law School, Delhi, Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University, talks about the need for a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) which is laid down as a Directive Principle of State Policy under Article 44 of The Indian Constitution. The writer tries to debunk certain myths associated with the UCC and how certain judicial decisions such as the Shah Bano Case and the Sarla Mudgal have played a decisive role in showing the pressing need for a uniform code for the country.

The term Uniform Civil Code (UCC) envisages administration of the same set of secular rules to govern people belonging to different regions and holding different religious beliefs. The term is used to denote a set of rules and regulations that govern all personal matters like; marriage, adoption, divorce, maintenance and inheritance- including matters related to property and personal status of citizens.

Article 44 of the Indian Constitution enshrines this principle as a Directive Principle of State Policy, it reads;

“The State shall endeavor to secure for the citizens a Uniform Civil Code throughout the territory of India.”

Though the exact outlines of such of code are yet to be spelled out it should presumably incorporate the most progressive and modern aspects from all existing personal laws of various religions while disregarding those who are regressive. As things currently stand in India, different communities have different laws governing different aspects of their daily lives, i.e. the laws governing inheritance and divorce among Muslims would be different from those of Christians and Hindus.

The Uniform Civil Code (UCC) is seen as the sign of a progressive nation; it shows that the nation has moved beyond the traditional demarcations based on religion, sex, caste and place of birth. It is seen as a beacon to facilitate much needed social growth in India along with economic growth.However, there are many who advocate that with the implementation of UCC the secular fabric of our country would be threatened, and it would be a potential threat to the religious freedom, especially for minorities.

Why UCC Doesn’t Limit Religious Freedom?

UCC does not limit the freedom of people to follow their religion; it means every person should be treated equally. Most of the personal laws have an inherent bias against the rights of women such as Unilateral Oral Talaq in Muslim Law, limited property rights of women in Christian Law or restitution of conjugal rights issue under Hindu Personal Law. This bias does not operate only against women, but also men.

The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, is the only personal law that provides for alimony from the wife to the husband, even the Foreign Marriage Act, 1969, or The Special Marriage Act, 1954, which are supposed to be gender neutral have no provision under which the husband can demand alimony from his wife. Similarly, personal laws do not provide for inter-religious marriages[1] thus prove to be divisive in society. Some benefits may also be considered unconstitutional for example, the Hindu Undivided Family gets tax exemptions, and Muslims must not register gift deeds; such benefits are based on religion and thus unconstitutional.

Further, an extra burden is added on the judiciary when different communities are governed by different laws. Bringing in a Uniform Civil Code would help reduce it and also help simplify a lot of technicalities and inherent confusions that are attached to present personal laws. Thus, addressing loopholes present in pre-existing personal laws.

Another important advantage of implementing the Uniform Civil Code is that it will bring an end to dirty vote bank politics which is relied upon by a majority of the political class to meet their ends. This is because if all of the India has the same set of laws governing it, then the politicians will have nothing to offer to the community on religious grounds in exchange for votes. The Supreme Court of India also has time and again reiterated the importance of enacting a Uniform Civil Code. During the Constituent Assembly Debates, B.R. Ambedkar had also demonstrated his will to reform Indian society by recommending the adoption of a Civil Code of western inspiration and he went on to add;

“I do not understand why religion should be given this vast, expansive jurisdiction, so as to cover the whole of life and to prevent the legislature from encroaching upon that field.”[2]

Every modern nation which has truly embraced ‘Secularism’ has a Uniform Civil Code.

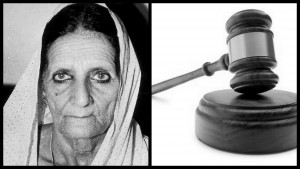

Shah Bano Case

The conflict between religious and secular authorities over the issue of UCC eventually subsided, until the advent of the Shah Bano case in 1985[3]. This case was controversial in many aspects, chiefly because it allowed for alimony and maintenance to Muslim women beyond the Iddat (or waiting) period. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled for Shah Bano Begun under the provision of Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which allows right to maintenance to a wife, and is applied to all citizens irrespective of religion.

“Under section 125 (1) (a), a person, who, having sufficient means, neglects or refuses to maintain his wife who is unable to maintain herself, can be asked by the Court to pay a monthly maintenance to her at a rate not exceeding five hundred rupees… ‘wife’ includes a divorced woman who has not remarried”[4]

The Supreme Court thus, allowed for maintenance of a Muslim woman post-divorce on a monthly basis. However, this became a largely debated controversy and in the wake of the Anti-Sikh riots of 1984, the minorities in India, felt a need to safeguard their interests and their culture, especially the Muslims, who are the largest majority in the country. Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure was seen as a threat to pre-existing Muslim Personal Law and the All India Muslim Personal Law Board members campaigned for complete autonomy in their personal laws and further accused the government of promoting and imposing Hindu dominance over all citizens at the expense of the minorities of the nation.

The Union Government fearing loss of a bulk of its Muslim vote share, overturned the decision of the of the Supreme Court in the Shah Bano Case and a legislation- The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986– was passed by the Parliament with full majority, though it was strongly opposed, and the government faced severe backlash from Muslim Liberals and women’s organizations. [5]

Sarla Mudgal Case

In the case of Sarla Mudgal[6], the issue of bigamy and the conflict between pre-existing personal laws on the matters of marriage were brought in front of the Supreme Court. It invoked Article 44 of the Constitution. This judgment is considered a landmark decision that accentuated upon the need for a uniform civil code in our country.

The Supreme Court said that it appeared that even after 41 years the Rulers of the day are not in the mood to fetch Article 44 from the “cold storage” where it has been lying since 1949. The governments which had so far come and gone had failed to any serious effort towards a unified personal law for all of the India. “When more than 80% of the citizens have already been brought under the codified personal law, there is no justification whatsoever to keep in abeyance, anymore, the introduction of Uniform Civil Code for all citizens in India.[7]

The apex court further observed that “It does not matter of doubt that marriage, succession and like matters of secular character can’t be brought within the guarantee enshrined under Article 25 and Article 26 of the constitution.” Further, in John Vallamattom v. Union of India[8], the Supreme Court again reiterated that a framing of a uniform civil code by the Parliament will be a great step towards removing contradictions of people based on ideologies and will lead to national integration.

The Road Ahead For Uniform Civil Code

The issue of implementation of a Uniform Civil Code has been severely politicized, with two upper sides that have now formed; the Congress along with Muslim conservatives versus the Right wing and Left. The debate over UCC is one of the most controversial issues in 21st century India with its manifold implications, mainly on the secularism of the country.

One of the major problems of implementing UCC is the diversity in religious laws of our country which differ by community, region, section, and caste. The seed of doubt in the minds of people- especially the minorities- that the religious ideologies of the majority religion will be imposed upon them is what needs to be eradicated, for an introduction of a draft of UCC and a subsequent smooth implementation.

Presently Goa has a common family law, also known as the Goa Civil Code. It is a set of civil laws that governs all Goans, irrespective of their religious beliefs; though it is quite different from a uniform civil code and has certain exceptions for some communities it shows that enactment of a uniform code is indeed quite feasible in India.

Bringing the UCC would help and reduce many technicalities and loopholes present in present existing personal laws, it was an aspiration of our Constitution makers. The Government must draft a common civil code with the view of all minorities and their best interests in mind; it must consult the Law Commission, National Commission for Women, National Human Rights Commission, Former Judges of Supreme Court, High Courts, Attorney Generals and Solicitors General. A sudden enactment might disrupt communal harmony. Thus a set of steady reforms is the must. The government must implement the uniform civil code in the true spirit of Article 44 of the Constitution.

Footnotes:

[1]http://www.oneindia.com/feature/why-india-urgently-needs-uniform-civil-code-2037892.html

[2]http://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/ambedkar-and-the-uniform-civil-code/221068

[3]Mohd. Ahmed Khan v. Shah Bano Begum (1985 SCR (3) 844

[4] Code Of Criminal Procedure, 1973

[5]http://www.youthkiawaaz.com/2012/06/the-shah-bano-case-a-landmark-case-in-indian-family-law/

[6]Sarla Mudgal, & others. v. Union of India,AIR 1995 SC 1531

[7]” http://centreright.in/2013/08/is-indianization-through-a-uniform-civil-code-a-communal-objective/

[8] (2003) 6 SCC 611

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications