In this article, Abeer Sharma pursuing Diploma in Entrepreneurship Administration and Business Laws from NUJS, Kolkata, discusses How the Presidential Election takes place.

The essence of the election process of the President of India is enshrined in Article 54 of the Constitution of India. In order to supplement and give shape to this Constitutional provision, the legislature has enacted the Presidential and Vice-Presidential Election Act, 1952, which is accompanied by the rules made under its authority, the Presidential and Vice-Presidential Election Rules, 1974.

The entire conduct of the Presidential election is held under the watchful eye of the Election Commission of India, which has the following responsibilities:

- Preparation of the electoral roll.

- Planning and execution of the electoral process.

- Ensuring that the election is conducted in a free and fair manner.

- Calculation of votes and declaration of the winning candidate.

Qualifying criteria for President

Any individual wishing to contest for the post of President must first ensure that he/she qualifies for the position, the criteria of which are laid down in Article 58 of the Constitution. These are:

- Must be a citizen of India.

- Must have completed 35 years of age.

- Must be eligible to be a member of the Lok Sabha.

- Must not hold any office of profit under the Government of India or the Government of any State or under any local or other authority subject to the control of any of the said Governments (Exceptions are the offices of President and Vice President, Governor of any State and Ministers of Union or State).

Explanation of Qualifying Criteria

Who is eligible to be a member of the Lok Sabha?

A Presidential candidate is eligible to be a member of the Lok Sabha when he conforms to the criteria which are laid down in the Indian Constitution (Articles 84 and 102) and the Representation of People Act, 1951 (Sections 8 to 10-A).

What is an office of profit?

The concept of “office of profit” was devised to maintain the independence of legislature and prevent the conflict of interest that would arise if an individual was both a member of the legislature as well as working in an executive role that would accrue to him any significant pecuniary gains. Under Indian law, an office of profit is any position or appointment made by or under the authority of the government – be it the Central Government, State Governments or local authorities. In case someone is the holder of such an office, he would first have to resign before contesting an election for President.

Eligibility Criteria for Electors

The President is the official Head of State, and is chosen with the help of an indirect election process by an electoral college consisting of the elected members of the Parliament of India and the Legislative Assemblies of the States and the Union Territories of Delhi and Puducherry.

What is an indirect election?

A direct election occurs when the citizens of a country vote directly for their representatives. For instance, the election process to the Lok Sabha is an example of a direct election.

An indirect election, on the other hand, is a process in which the ultimate voters (i.e. the citizens) don’t get to choose the candidate, but rather choose electors who will subsequently make the decision for them.

What is the exact composition of the Presidential Electoral College?

While the Electoral College comprises of legislators, not all members of the legislative branch are eligible to be electors in the Presidential election. Legislators can be grouped into two categories based on how they ascend to their position:

Elected members: These are legislators that have been chosen after undergoing the process of an election. In the case of the Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assemblies, this refers to individuals who have become members as a result of the general elections and state legislative elections, respectively, and in the case of the Rajya Sabha it refers to individuals who have become MPs after an election has been held in their relevant State Assemblies.

Nominated members: These are legislators that are appointed to their post by the President or Governor (as the case may be) without undergoing an electoral process. Nominated members include the following:

- 12 members nominated to the Rajya Sabha by the Central Government amongst persons who have special knowledge or practical experience in respect of such matters as literature, science, art and social service.

- 2 members nominated to the Rajya Sabha by the Central Government to represent the Anglo-Indian community

- 1 member nominated to the State Legislative Assembly by the State Government in case it feels that the community is underrepresented. Every State is empowered to make this nomination.

Out of the Indian Parliament (both houses) and the State Legislative Assemblies, only the elected members are eligible to participate as electors in the Presidential Election. The nominated members are, correspondingly, ineligble. Additionally, members of the Vidhan Parishad (in states which have one) are not eligible to be part of the electoral college.

Are legislators from Union Territories eligible to be part of the electoral college?

As a result of the 70th Amendent Act to the Indian Constitution, elected Legislative Assembly members of the Union Territories of Delhi and Puducherry are also to be included in the electoral college. The other UTs do not have a Legislative Assembly.

Voting Shares of the Electoral College

Not only is the election of the President conducted through an electoral college, but it also doesn’t follow the concept of “one man, one vote.” Given the fact that the election is an indirect one, and geared to represent the choice of the country as a whole, the Constitution prescribes a specific formula to calculate the value of the vote cast by every elector.

Given that the national parliament as well as the state legislatures participate in this electoral process, the formula calculating the the weightage of votes is based on two fundamental principles:

Uniformity

The formula aims to secure uniformity in the scale of representation of all the different States in the country, to emphasize the equivalent status of all States despite the differences in their size, population, or other characteristics.

Parity

The formula tries to secure parity between all the States as a whole and the Union in order to uphold the idea of a federal government structure.

The formula provides for different methods of computing the vote weightage for MPs and MLAs.

Calculation of the vote share of an MLA

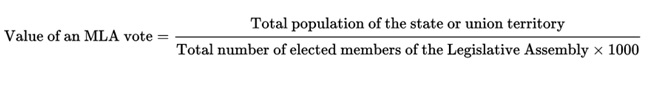

The formula for calculating the vote share of an MLA can be represented as follows:

Calculation Note: Calculations that end in fractions exceeding 1/2 will be rounded up to the nearest whole number, whereas fractions of less than 1/2 will be rounded down.

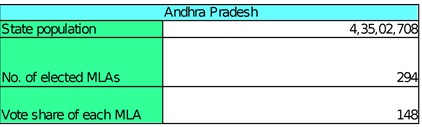

The way this formula operates can be better illustrated through the following hypothetical example of the State of Andhra Pradesh:

Step 1:-

Multiply the total number of elected MLAs with 1000:

294×1000 = 2,94,000

Step 2:-

Divide the State population by the result of Step 1:

4,35,02,708/2,94,000 = 147.968

Step 3:-

Given the fact that the result of step 2 is a decimal number, and the decimal part is a fraction greater than 1/2 (or, in other words, more than .5), the number will be rounded up to the nearest whole number, giving us the value of 148.

Important Note: Originally, the Constitution intended the population figures to be continuously updated to reflect the results of the immediate preceding census. However, in order to promote family planning measures throughout the country, the Parliament passed the 42nd Amendment Act which was later updated by the 84th Amendment Act. According to the 84th Amendment, the census figures of 1971 are to be taken as the population of each state, and these figures will be in operation until the first census after the year 2026 is conducted. In other words, the 1971 population figures will be fixed until the 2031 census, and the 2032 Presidential election will be the first Presidential election to use updated population figures.

Calculation of the vote share of an MP

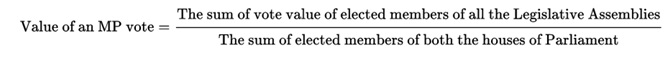

The formula for calculating the vote share of an MP can be represented as follows:

It can be deduced from this formula that the value of an MP’s vote is directly dependent on the vote value of all MLAs. The following steps will be required in order to get the final value:

Step 1:-

Calculate the value of the votes of all MLAs from every state in accordance with the formula prescribed in the section above and then find the grand total of these values

For instance, if the value of the vote of an MLA from Andhra Pradesh is 148 and there are 294 elected MLAs, then the total vote share of Andhra Pradesh will be 148×294 = 43,512

Repeat this process for each state and then add up all the total vote shares of each state to find the sum of vote value of elected members of all the Legislative Assemblies.

Step 2:-

Divide the grand total value found in Step 1 with the total number of elected members in both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha (543+233 = 776). The resulting number will be value of the vote held by every MP.

As can be seen from everything detailed above, the “voting power” of each elector varies depending on whether they belong to the Union or the State legislature, or which State they belong to in the latter case.

What if a State’s Legislative Assembly has been dissolved?

It must be remembered that the calculation of vote shares will be dependent on the number of State Legislative Assemblies which are in existence at that point of time. Therefore, if President’s Rule under Article 356 of the Constitution has been imposed on a State and it hasn’t been re-constituted in time for the President’s election, the election will go on regardless. The legislators who were in power prior to the dissolution of the Assembly will not be eligible to qualify as electors, and the MP vote shares will be calculated wihout factoring in their vote values. However, it is the moral responsibility of the Election Commission to schedule elections in such a manner that they may be as representative of the nation’s will as possible.

Conduct of Election

Preliminary Activities

The Election Commission shall publish a notice informing the public about its plans to conduct the Presidential Election at the specified dates and venues. Prospective candidates can begin planning their election game-plan following this notice.

In order to secure one’s Presidential candidature and contest the elections, the interested individual has to complete a few specific procedural tasks, aside from filling out the requisite paperwork and declarations:

Securing nominations

To be eligible for the electoral process, a candidate must get his nomination papers signed by 50 electors as proposers as well as 50 electors as seconders.

Paying the Security Deposit

A prospective candidate is also required to submit a security deposit of Rs. 15,000 along with his nomination papers. This deposit will normally be refunded to him, unless he loses and the number of votes he got is less than 1/6th of the amount he would have needed in order to win the election. The amount of votes he would’ve needed in order to win is, of course, a variable number and depends upon the number of candidates contesting the elections and the number of electors present.

System of Election

The election of the President of India is achieved through the system of proportional representation by single transferable vote.

The way this works can be illustrated in the following way:

- Suppose there are five candidates in a particular election.

- All members of the Electoral College will be required to mark their preferences on their ballots. In other words, they will have to rank all five candidates from 1st to 5th.[1]

- After everyone has cast their vote, the counting process takes place.

- In order to be declared the winner, a candidate is required to get the prescribed quota of votes. The winning quota is determined by the following formula:

- Winning quota = 50% of all valid votes polled[2] +1

The value of votes a contesting candidate gets in the first round is determined in the following way:

Number of ballots on which candidate is first preference X Value of vote which each ballot paper of a member (MP or MLA) represents.[3]

If the election took place under the rules of the first-past-the-post system, then figuring out the winning candidate would have been quite straightforward – the candidate with the most number of votes, no matter by how small a margin, would be elected President. However, under the proportional representation by single transferable vote system, it is not necessary that the election will be completed in a single round.

In fact, there are a number of different ways the electoral process could pan out, depending on the total value of votes each candidate obtains in the first round.

To understand this process better, assume that the total value of all votes in an electoral college is 200[4].

Scenario A

FIRST ROUND OF COUNTING

| Candidate | Valid Votes Polled |

| A | 15 |

| B | 103 |

| C | 25 |

| D | 36 |

| E | 21 |

| Total | 200 |

Keeping in mind the formula for the winning quota, a candidate needs to obtain at least 101 votes ([50% of 200] +1) in order to be declared the winner.

If the breakup of the votes polled ends up the way described above, then Candidate B will be declared the winner.

Scenario B

However, what if after the first round of counting, no clear winner emerges?

FIRST ROUND OF COUNTING

| Candidate | Valid Votes Polled |

| A | 30 |

| B | 60 |

| C | 40 |

| D | 23 |

| E | 47 |

| Total | 200 |

Given that nobody managed to reach the necessary quota of 101 votes, there will be a need to rely on subsequent rounds of counting.

The returning officer will exclude the candidate with the lowest number of first preference votes, which in this case is Candidate D. The 23 votes obtained by candidate D will be distributed amongst the remaining candidates.

This is where the preferences of each elector become relevant. Those 23 votes which originally belonged to D will be distributed among the remaining candidates keeping in mind the second preference of each elector.

For instance, out of the 23 votes that D obtained:

- 12 had B as the second preference

- 5 had E as second preference

- 5 had C as second preference

- 1 had A as second preference

These three candidates will receive these votes at the same value that C originally got them. The resulting vote shares of the remaining candidates would look like this:

SECOND ROUND OF COUNTING

| Candidate | Valid Votes Polled |

| A | 31 (30+1) |

| B | 72 (60+12) |

| C | 45 (40+5) |

| E | 52 (47+5) |

| Total | 200 |

As can be observed here, even after distributing the vote shares of the eliminated candidate, none of the remaining candidates have managed to reach the winning quota. Therefore, the process of elimination will have to be undertaken once again.

Now it can be seen that Candidate A has the lowest tallied votes. As a result, the number of votes he has gotten will be distributed among the remaining candidates.

Important note: It must be remembered that in the first round of distribution, one of Candidate D’s original vote shares had labelled Candidate A as the second preference. Therefore, when distributing that particular vote share, the returning officer will look at the third preference. The rest of the votes being distributed have A marked as the first preference, therefore the returning officer will look at the second preference marked and allott them accordingly (except for cases where the second preference is a candidate who has already been eliminated, in which case the returning officer will look at the third preference).

Out of A’s eliminated 31 votes, the returning officer finds that:

- 27 of A’s original votes have marked Candidate B as the second preference

- One of Candidate D’s original votes – which had been assigned to A after D was eliminated – has marked candidate B as the third preference

- Two of A’s original votes have marked Candidate E as the second preference.

- One of A’s original votes has marked Candidate D as the second preference. However, since D was eliminated after the first round, the returning officer looks at the third preference for that particular vote, which has been assigned to B.

After factoring in all this information, the returning officer will begin the third round of counting, the results of which will be as follows:

THIRD ROUND OF COUNTING

| Candidate | Valid Votes Polled |

| B | 101 (72+29) |

| C | 45 |

| E | 54 (52+2) |

| Total | 200 |

Given that Candidate B has attained the winning quota after the third round of counting, he shall be declared the winner of the Presidential Election.

The scenarios highlighted above are an extremely rudimentary illustration of how the system proportional representation by single transferable vote takes place. In a real presidential election, the returning officer would be dealing with the votes of thousands of individuals, and he would have to keep in mind all the different values of their votes, depending on their designation and the State they’re from. He would have to take note of complex preference variations (some electors may even choose not to assign all preferences), and would have to eliminate invalid votes from valid ones. With the advent of electronic voting, however, the entire electoral process has become a whole lot more streamlined and efficient.

References:

The Constitution of India

Representation of People Act, 1951

Presidential and Vice-Presidential Election Act, 1952

Presidential and Vice-Presidential Election Rules, 1974

Press Information Bureau. ELECTION OF THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA – Backgrounder. 2017. Web. 29 June 2017. (The example and figures of Andhra Pradesh has been taken directly from this source)

[1]It is not necessary that an elector must mark all of his preferences on the ballot paper. It is even acceptable if he only marks his first preference and leaves the rest blank.

[2]A vote is considered valid if the ballot paper conforms to all the criteria laid down by the Election Commission. In case a ballot paper doesn’t match up to those criteria (for instance, if it has two candidates marked as first preference or any other defects), then it is deemed invalid and is excluded from the counting process entirely.

[3] As has been mentioned earlier, the votes of all members will not be treated equally. For example, the vote of a single MP will be given more weightage than the vote of a single MLA. Similarly, there will be different values ascribed to the votes of MLAs of different states.

[4] This is an extremely simplified example used for the sake of convenience. The actual total value of votes in a real Presidential election is invariably a far greater amount. Further, this illustration doesn’t break up the value of votes among individual members depending on their status.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications