This article is written by Khyati Basant, from Symbiosis Law School, NOIDA. This article consists of a descriptive discussion of the religious practices in India and the evolution of Article 17 of the Constitution of India.

Table of Contents

Introduction

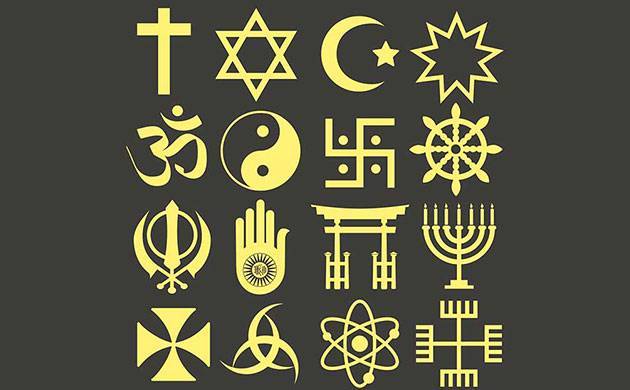

India is one of the most religiously diverse nations and it is the birthplace of four major world religions: Jainism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism. While Hindus form nearly 80 per cent of the population, India also has region-specific religious practices: for example, Jammu and Kashmir have a Muslim majority, Punjab has a Sikh majority, Nagaland, Meghalaya and Mizoram have Christian majorities and Indian Himalayan states such as Sikkim and Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh and the state of Maharashtra and the Darjeeling district of West Bengal have Buddhist population. The country has significant populations of Muslims, Sikh, Christians, Buddhists, Jain, and Zoroastrians. Islam is India’s largest minority faith and the Indian Muslims make up the world’s third-largest Muslim group, making for more than 14 per cent of the nation’s population. Rajni Kothari, the founder of the Developing Societies Study Center, said, “India is a society founded based on a profoundly egalitarian culture.”

Religion is an important element in India. However, one can not argue that in India, mainly, religious personal laws are the root of prejudice, unlike other countries where it resulted from the codification of the biases of the powerful. Given these inconveniences, it is difficult to classify an individual without reference to his or her faith because India is a strongly religious community and a multicultural state. Religion in India is not only an issue to solve in such a situation but also a force to handle. Nevertheless, the State’s failure to establish any effective structure to accomplish the constitution’s fundamental purpose, i.e. pursuing amelioration of people’s social circumstances long burdened with inequities by religiously-based hierarchies, has forced the judiciary to take a remedial step. Even though faith was inscribed in daily social norms in India, the judges needed to skip the religious conflicts. The Judiciary eventually proceeded to apply the theory in cases that aimed to bring about social change.

More often than not, the judiciary has been burdened with interpretive responsibilities which go beyond its field of expertise. Such an effort by the courts, while important to guarantee people’s rights, has been dismissed as an interventionist strategy by many academics. So much so, the scholars believe that such an approach has led the Tribunal to become a seat of theological authority rather than a constitutional authority.

Religion in India

In India, the need to describe religion was first raised by Dr B.R Ambedkar when the Constituent Assembly debated the question of moral rule and its relationship to religion. He pointed out: In this nation, the religious conceptions are so vast that they encompass every part of life from birth to death. There is nothing that is not faith, and if the personal rule is to be protected, I am sure that we will come to a standstill in social matters. There is nothing exceptional to suggest that we will try to narrow the concept of religion in such a way that we do not expand it beyond values and practices that might be associated with ceremonies. Under Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s opinion, what constitutes a ‘religion’ or ‘holy matter’ is to be ascertained by limiting to holy practices and ceremonials which are regarded as inherently religious under a specific religion under judicial scrutiny. There is no clear definition of ‘religion’ or ‘religion exists’ in the Indian Constitution. Under Article 32 of the Constitution Directive which grants the right to Constitutional remedies is left to the Supreme Court to draw a legal decision to grant the fundamental rights to the citizens. In the early 1950s, in several cases, the Indian courts had faced the problem of defining ‘religion’ as provided for in Article 25(1) and ‘religion matters’ as provided for in Article.

Constitution and Religion in India

The Constitution uses the terms ‘religion’ and ‘religious faith’ but does not describe them and so the courts felt it appropriate to clarify the meaning and connotation of these words. The Supreme Court noted that: We may conclude that religion is a matter of faith in the context of the constitutional guarantees and the light cast by the judicial precedent. It’s about conviction and doctrine.

In constitutional terms, India is a secular country, but there is no “wall of separation” between faith and state either in law or in practice — both will, and sometimes do, interfere and participate in each other’s affairs beyond the limits constitutionally specified and judicially decided. Indian secularism does not entail a complete banishment of faith from the affairs of a society or even of administration.

The only requirement of secularism, as provided by the Indian Constitution, is that the State shall handle all religious creeds and their respective followers in all matters under its direct or indirect jurisdiction completely fairly and without prejudice. India is an excellent environment as a culturally mixed society and self-proclaimed secular state for investigating the dynamic and sometimes contentious connections of religion and law. The Indian Constitution’s provisions on religious freedom empower the state to control and prohibit other non-religious practices. The judiciary plays a significant role in deciding the degree to which the state can constitutionally govern religious affairs by reading the constitutional protections on religious freedom.

Which particular rights to freedom of faith should be protected? What limitations are allowable on certain freedoms if any? Who has the authority to determine the religious scope? How should the government deal with cases where one group’s religious freedom conflicts with that of another? Or were rights that are protected by freedom of religion conflict with other fundamental rights? Such difficult questions must be answered to turn a compelling but ambiguous definition into solid public policy.

The right to freedom of worship is one of the rights granted in the Indian constitution. As a secular nation, every Indian citizen has the right to religious freedom, that is to say, the right to follow any religion. The constitution guarantees every citizen the freedom to follow the religion of their choice, as one can find so many religions being practised in India. Each person can practise and spread their faith peacefully according to this constitutional right. So if there is some incident of religious intolerance in India, it is the Indian government’s responsibility to curtail such incidences so take stern action towards them.

India’s constitution guarantees the protection of certain fundamental rights. They are given in Articles 12 to 35 of the Constitution, which form Part III to the constitution. The two central articles guaranteeing religious freedom are amongst them Articles 25 and 26.

Article 25

It reads any existing law or prevents the State from making any law — (a) regulating or limiting any economic, financial, political or other secular activity that may be associated with religious practice; (b) providing for social welfare and reform or opening up to all classes and sections of Hindus religious institutions of a public nature. The freedom of religion of the individual guaranteed by the Indian Constitution is provided for in Article 25, Clause (1), which reads: subject to public order, morality and health and to the other provisions of this Part, all persons are equally entitled to freedom of conscience and the right to profess, to practice freely. The Constitution makes it clear, in precise terms, that the rights provided for in clause (1) of Article 25 are subject to public order, morality and health and to the other provisions of Part III of the Constitution which lay down fundamental rights. Clause (2) of Article 25 is a safeguard clause and it states that Nothing in this Article shall influence the implementation of any current legislation or prohibit the State from implementing any legislation:

(A) the control or restriction of any cultural, social, political or other secular existence.

Activities which may be related to religious practice.

(B) providing for social security and changing or opening up the Hindu.

To all classes and groups of Hindus, religious bodies of public character.

The wearing and carrying of kirpans shall be deemed to be part of the Sikh religion profession. Explanation II In sub-section (b) of the Hindus relation section, As relating to people who follow the Sikh, Jaina or Buddhist faith, for a State so that the religious right guaranteed under Clause 1) is further subject to any existing law or legislation that the State considers fit to pass that (a) regulates or restricts any economic, financial, political or other secular activity that may be associated with religious practices, or (b) provides for social welfare and reforms for all classes.

A good reading of Article 25 is important for the comprehension of the creation of the evaluation of critical activities. Even more so than Article 26, despite the influence of constitutions of other nations, the provisions of Article 25 are highly specific to the socio-political context of India.

Article 26

Any religious belief, or religion, subject to public order, morals and fitness. Any part of it shall be entitled as-

(A) The creation and maintenance of religious and charitable institutions;

(B) Administering its religious affairs;

(C) To possess and hold movable and immovable property; and

(D) The management of such land in compliance with regulations.

Article 26 is the principal article providing for the freedom of enterprise and religion regulating the relationship between the State and Subject to public order, morals and welfare, all religious sects or portions thereof shall have the freedom to (a) create and preserve religious and charitable institutions; (b) administer their religious affairs; (c) own and possess movable and immovable property, and (d) administer such property; Clause (b) of Article 26 grants to of religious group or any part thereof the freedom to control its affairs in matters of faith and clause (d) gives it the freedom to administer its properties (institutions) in compliance with the laws passed by the Parliament.

From the vocabulary of clauses (b) and (d) of Article 26, it is clear that there is an important distinction between a denomination’s right to control its religious affairs and its right to control its properties. This means that the right of a religious denomination to administer its religious affairs is a constitutionally protected fundamental right. Save for fitness, morals and public order, no law can contradict it. However, the freedom to control religious properties should only be practised in compliance with the statute. In other words, the State may govern the administration of religious properties by-laws which have been passed validly.

In the exercise of individual and corporate religious freedom as enshrined in Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution of India, the judicial definition of ‘religion’ as provided for in Article 25(1) and ‘religious matters’ as provided for in Article 26(b) must be recognized. Defining religion for judicial purposes has been an onerous job for the judiciary in both the Western and Indian countries.

The higher courts in the country have applied and interpreted all constitutional provisions and legislative acts relating to religion and religious rights and freedoms in different ways. These judicial decisions, read together, define the role of religion in state affairs and the role of the State in religious affairs, in addition to setting out the contours of individuals and communities’ religious rights and freedoms. India’s judiciary has been particularly engaged in the adjudication of religious matters. It has resolved many religious disputes between the people and the state on the one hand, and between different communities, sects, and groups on the other, during the process of reviewing these matters.

From our discussion above, it can be concluded that Articles 25 and 26 are meant to direct the life of the nation and to ordain any religion to behave in compliance with its cultural and social demands to maintain an equal social order. Consequently, it should eradicate inequalitarian social practices. Such a mechanism requires the Court’s adjudication of matters to give substance to the attempts for social change. The approach adopted by the Indian courts, i.e. resorting to the test of basic religious beliefs, can appear to be an interventionist approach, thereby eventually contributing to the issue of the lawfulness of the test itself in a secular country like India.

Judicial Perspective

- The freedom to religion granted under Articles 25 & 26 is not absolute or unfettered; it is subject by the State to the regulation of social services by effective legislation. Therefore, when reading Articles 25 and 26, the Court strikes in A.S. Narayana Deeshitalyu v State of Andhra Pradesh a careful balance between matters that are important and fundamental and those that are not, and the need for the State to govern or control the interests of the group.

- Articles 25-30 embody the principles of religious tolerance which have been characteristic of the Indian civilization since the beginning of history. They serve to underline the secular nature of Indian democracy that the founding fathers believed should be the very foundation of the Constitution in Sardar Syedna Taiiir Saifiiddin v State of Bombay.

- Tilkayat Shri Govindlalji Maharaj v. State of Rajasthan When cases on contentious matters have been brought before the Indian court’s issues about ‘political matters’ as referred to in clause (b) of Article 26 of the Constitution, judges referred to textual references as well as current religious beliefs and traditions under review to determine their basic aspects as stated by the petitioners or the candidate. Throughout this regard, it is insightful for us to review the Tilkayat issue, which sheds more light on the Indian judicial stance on ‘political issues’ as provided for throughout Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution. The Tilkayat lawsuit emerged from Rajasthan’s Nathdwara Temple Act passed by a commission to run the Nathdwara shrine. Section 16 of the Act states that, according to the provisions of the Act and the rules rendered therein, the Board is responsible for maintaining the property and “temple relations” and organising the conduct of regular worship and rituals and festivals in the temple “in compliance with the rites and uses of the religion” to which the temple belongs.

- In Ratilal Panachand Gandhi v State of Bombay, Freedom of conscience connotes the right of a person to hold opinions and theories concerning subjects that he finds conducive to his moral well-being. Religious practices or acts in the service of religious principles are as much a part of faith or conviction in particular doctrines. The Ratilal case was again appealed to the Supreme Court to decide the judicial interpretation of ‘faith’ and ‘religious matters’ as provided for in the freedom to practice faith protected by Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution. The case arose from the Bombay Public Trust Act, enacted by the Bombay State Legislature in 1950. Similar to the Madras Act of 1951, the purpose of the Bombay Act, as stated in its preamble, was to regulate and make better provision for the administration in the State of Bombay of public religious and charitable trusts.

- In Seshammal v State of Tamil Nadu AIR 1972 SC 1586, what constitutes an integral or essential part of a religion or religious practices shall be decided by the courts concerning the doctrine of a particular religion and shall include practices considered by the community to be parts of its religion. The right to believe, observe and spread religion should not apply to the right to worship in any or all places of worship, such that any obstruction to worship in any particular place in itself will infringe religious freedom. This was discussed in the case of Ismail Faruqui v Union of India.

- Mohammad Hanif Quarashi v. The State of Bihar -The Qureshi case is about banning cow slaughter. It has a long tradition in the constitution. India’s Constitution has other guidelines for States that they have to take into account when implementing their policies. The Concepts of the Directive vary from the rest of the Articles of the Constitution in the way that they are unjustifiable because they have no moral power to bind them. That is if the State acts in a manner contrary to the Directives set out in Part IV of the Constitution; it can not challenge its action in the Court. It is nonetheless held that the principles of the Directive are important. Their value, as M.C. commented, consists of. Setalvad, a former Attorney-General of India, said that “they tend to be an instrument of guidance or general advice addressed to all the institutions in the State, informing them of the basic values of the current social and economic structure that the Constitution intends to create.” The aims of this essay are the growth of farming and animal husbandry on modern and science terms, as well as the protection and advancement of cattle breeds, and the prohibition of the slaughter of .cows and calves. It seems that the Supreme Court’s decision on this case has taken into account as one of the important factors the Hindu religious feelings added to the cow slaughter prohibition law. The Court was, of course, more concerned with communal riots that frequently occurred because of cow slaughter. The Honorable Judges of the Quarashi case acknowledged, “While we agree that the constitutional question before us can not be decided on merely sentimental grounds, however passionate it may be, we nevertheless believe that it must be taken into account in reaching a judicial decision as to the reasonableness of the restrictions, albeit only as one of many elements”

- Commissioner, Hindu Religious Endowments, Sri Shirur Mutt: Madras v Lakshmindra Thirtha Swami, the issue of Shri Shirur emerged from the 1951 Madras Hindu Religion and Charitable Endowments Act passed by the 1951 Madras legislature. As specified in its preamble, the object of the Act was to reform and simplify the legislation relating to the administration and management of religious and charitable Hindu institutions and endowments in the State of Madras. The Act contained sections dealing with the State’s powers concerning the general administration of Hindu religious institutions, their finances and certain other diverse subjects. According to Article 25 ‘propagating’ religion means ‘propagating or disseminating his ideas for the building up of others’ and for this right it is immaterial ‘whether propagation takes place in a church or a monastery or a temple or parlour meeting. The Supreme Court found the case to be statistical. While giving the judgment, it appears that the Court has taken a thoughtful approach to the meaning of “religion.” Besides, the Supreme Court seemed to have given an indigenous meaning to what is included in the category of religious-related “secular activities” This Supreme Court judgement has been regarded as one of the most relevant rulings on the concept of religion in Indian jurisprudence. Mr Justice Mukerjea, who argued in support of the Court’s unanimous ruling, pointed out that the conflict settlement was focused on clarifying what ‘religious issues’ are.

- The word ‘holy matters’ in Article 26 applies to religious activities and includes rites, observances, ceremonies and worship modes —in the case Jagannath Ramanuj Das v State of Orissa

The Concept of Secularism in India

Despite the clear incorporation of all the basic principles of secularism into various constitutional provisions when originally enacted, its preamble did not then include the word ‘secular’ in the country’s short description, which is called a ‘Sovereign Democratic Republic.’ This was not an inadvertent omission but a well-calculated move to prevent any misgivings that India should follow some of the secular state’s western conceptions. India is officially a secular nation and has no official religion. Over the years, however, it has developed its own unique concept of secularism which is fundamentally different from the parallel American concept of secularism requiring complete separation of church and state, as well as from the French ideal of la cite – described as ‘an essential compromise whereby religion is entirely relegated to the private sphere and has no place in public life at all. Twenty-five years later, after India’s definition of secularism was completely developed by court rulings and state law, the preamble to the Constitution was modified by the 1976 Constitution (Forty-second Amendment) Act to incorporate the terms ‘secular’ and ‘socialist’ to declare India a ‘Sovereign Socialist Secular Democratic Republic.’

We are a secular nation, but there is no ‘wall of separation’ between religion and the State in this world, not in law nor reality – the two will, and sometimes do, interfere and participate in the affairs of each other within the limits constitutionally defined and judicially decided. Indian secularism does not entail a complete banishment of faith from the affairs of a society or even of the State. The only demand of secularism, as prescribed by the Indian Constitution, is that the State should treat nil religious creeds and their respective adherents in all matters under its direct or indirect control, absolutely equally and without discrimination.

In the leading case of S.R. Bommai v Union of India different Supreme Court of India judges explained separately the nature and position of secularism under the Constitution in very specific terms summarized below: The Constitution preferred secularism as its mechanism for the creation of equal civil order. Secularism is part of the fundamental law of the Indian political system and its basic structure. Since the very beginning, secularism became very much rooted in our constitutional ideology.

What was implied by this amendment was made explicit? Constitutional provisions prohibit the establishment of a theocratic State and prevent the State from identifying itself with any particular religion or favouring it otherwise. Secularism is more than a passive tolerance of religion. It is a positive conception of all religions being treated equally. If the State allows people to observe and confess their faith, it does not allow them to incorporate faith into non-religious and secular State practices either directly or indirectly. Religion’s freedom and tolerance are only to the extent that it allows for the pursuit of a spiritual life that is different from secular life. The latter lies under the State’s exclusive sphere of affairs.

The Supreme Court in Sri Venkataramana Devaru v. The State of Mysore referred to the concept of sacred practices when considering whether the prohibition of such individuals, i.e. the untouchables from entering a Hindu temple, was an important part of Hinduism. In such a scenario, the doctrine of essential practices was rather a progressive test designed by the Apex Court to decide on matters of religion to preserve the main facet of our Constitution, i.e. secularism.

Indeed, these conflicts resulting from the controversy between religious freedom and state interference to bring about social reform led to the introduction of the word “secular” by the forty-second amendment into the Preamble to the Constitution of India to reaffirm the State’s purpose to be impartial against all religious affiliations. It is not surprising that the essential doctrine of religious practice came into being long before the introduction of the term ‘secular’ in 1976 because the apical court had to believe that the only way to reaffirm the concept of a secular state would be by separating what is essential from a religion.

Evolution of Article 17 in India

Dr B.R. Ambedkar, the chief of the oppressed classes, proclaimed, “Asking people to give up caste is asking them to go against their simple religious doctrines.” Among Hindu society’s multitudinous caste divisions, it was the people who belonged to the untouchable castes who endured maximum disabilities and received the most uncivilized treatment for ages from their fellow religionists. For centuries, people of the untouchable castes were treated as slaves in most Hindu kingdoms, particularly in South India. The practice of caste-based untouchability has been a blot on the Indian society. We are concerned here with the practice of untouchability whereby a certain section of the Indian community was shunned and in the past excluded from religious practices in the Hindu temples on account of their birth or profession. Different ideas and views have been brought out on the roots of the caste system, and untouchability is viewed by some as part of Hinduism, and by others as simply a social arrangement established in India. The egalitarian society of individuals has become the legal basis of social order, as opposed to a hierarchy of lower and higher individuals before the law.

Equality before the law and equal protection of the law were the positive expressions of that principle as laid down in Article 14 of the Constitution, which reads: ‘The State shall not deny any person equality before the law or equal protection of the laws in the territory of India. Determined efforts were made before the creation of the Constitution by Indian reformers to abolish untouchability in many parts of the country. These efforts had helped many states to pass laws during the British Raj banning the practice of untouchability in any way these efforts received constitutional expression in Article 17 of the Constitution, which abolished untouchability and made its implementation a criminal crime in any way. Article 17 notes that “Untouchability” is eliminated, and that its existence is forbidden in some manner. The violation of any condition that results from “Untouchability” shall be an offence punished by statute.

In 1955, the Parliament passed the untouchability according to Article 17 (Offenses) Act imposing punishments for untouchability activities. This Act extends not only to Hindus but also to all those who engage in the ex-communication or imposition of some social condition on any person who fails to practise untouchability. Concerning the practice of religion and untouchability, the Act makes it a crime to bar any person from entering public veneration due to the practice of untouchability.

The Act states: (I) whoever, on the grounds of untouchability, forbids any person from entering any place of worship open to other individuals who practise the same religion or belong to the same religious group or any part thereof, as such; or (ii) from the worship or offering of prayers or the delivery of any religious activity in any place of public worship, in the same way, and to the same degree as is allowed for other individuals professing the same religion or belonging to the same religious faith or any part thereof as these individuals; shall be punished by incarceration of up to six months or by a fine which may be levied on them.

The term untouchability was described in the Devarajah v. Padmana trial. It has been noted that the 1955 Untouchability Offences Act does not describe the term ‘untouchability.’ The Court noted that ‘untouchability’ should not be taken in the strict sense under Article 17 of the Constitution but should be interpreted as a tradition which has existed and evolved in India. The Constitution’s framers have specifically suggested untouchability as a custom that has evolved in this country historically. The presence and nature of untouchability in this country and the attempts made to abolish it over the last few decades are matters of common knowledge and can be considered judicially. Article 17 is a special law abolishing ‘untouchability’ and in every way banning its operation. One of the fundamental values of a secular democratic State is the right to equality before the law and equal protection of the law for all citizens regardless of religion, race, sex and place of birth. Article 17 of the Constitution, meant to eliminate the tradition of untouchability, does not describe the word ‘untouchability’ nor is it specified elsewhere in the Constitution. The Court provided a wider definition of the term ‘untouchability’ according to Article 17 of the Constitution.

Case laws

The State of Karnataka v. Appa Balu Ingale – In this case, the accusation against the respondents was that they had forcibly restrained the complainant from taking water from a newly dug-up borewell because they were untouchable. K. And Ramaswamy, J. “The purpose of Article 17 and the Constitution (Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955) is to liberate society from blind and ritualistic conformity to cultural values that have destroyed their ethical or moral roots. This aims to create a new paradigm for society — equality for the Dalits, on an equal basis with the general population, lack of disability, limitations or bans on caste or faith grounds, abundance of resources, and a sense of becoming a member in the mainstream of natural life.

State M.P. And Another v. Ram Krishna Balothia and Another – In this case, the Supreme Court held that section 18 of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 which contains the non-applicability of an anticipatory bail provision according to sec. 438 cr. p.c. Arts shall not be violated in respect of offences under Section 3 of the Act. 14 and 21 Under the Constitution.

Suhasini Baban Kate (Sou.) v. State of Maharashtra Insult offence on the ground of untouchability. The complainant was a 30-year-old woman. Her credit has had no bad antecedents. She was a wife with three sons, the youngest being one year old. The alleged occurrence happened on the spur of the moment and all of a sudden the alleged utterances were probably from the momentary rising in temper. The complainant did, above and above those naked assertions. She was held in detention for 3 days, however. Given the severity of the crime, it was considered unfair to bring her off to jail so she may well be released under the probation that had already been served in the interests of justice, even if the mandatory term was one month.

The Sabarimala Case

The controversy surrounding a recent decision by the Supreme Court illustrates the social and legal magnitude of adjudication of religious freedom in India. Here, to illustrate the significant social implications of the approach of the Supreme Court, we must forecast this event and foreshadow the conclusions of the following pages. The case popularly known as the Sabarimala case refers to a Hindu temple situated in Kerala’s south district. Devotees making pilgrimages to Sabarimala typically observe forty-one days of austerity, fasting, celibacy, and purification known as vratham preceding their temple worship.

Besides, many pilgrims make an arduous journey to the Sabarimala temple on foot through remote mountains and forests, some as long as sixty kilometres. Although some have given arguments related to women’s health and welfare, religion is the primary rationale for the ban. It is believed that a dedicated celibate or Brahmachari is Lord Ayyappa, the Deity associated with the temple. The implication is that the presence of women at the temple would offend the divinity. Others point to menstrual impurity or the possibility of women distracting male devotees and interfering with their vratham practices. Two women violated the long-standing ban in early 2019 and joined the temple of Sabarimala for worship. Their actions were motivated by the 2018 court verdict, which declared the ban on women’s entry unlawful and ordered the municipal police to protect all women who attempted pilgrimages. The Sabarimala verdict was faced in the state of Kerala with serious resistance. Protests and protests have turned violent. The riots were attributed to several deaths, and many buses, police vehicles, businesses, and offices were damaged or destroyed. The government shut down schools and public transport across the state as a safety measure.

The greater controversy surrounding the verdict spread far beyond the state and became nothing short of national outrage. Protests took place in both Delhi and Mumbai, several of the nation’s most influential politicians and commentators commented on the issue, and news channels followed the story for countless hours. In the wake of the Sabarimala verdict, I do not wish to simplify the complexities which precipitated such turmoil. Nevertheless, there is a perception among them that the supposedly secular government has neglected to preserve the religious feelings of the Hindus of millions in India. Consequently, a sacred shrine has become a place of confrontation. Indian Young Lawyers Association v. The State Of Kerala is the name of the notorious trial.

In 1991, the Kerala High Court found the constitutionality of the ban on women, and upheld the prohibition as “in keeping with the practice prevailing from time immemorial.” In 2018, the issue was again raised in the Supreme Court, which set aside the earlier ruling. The Court found the ban on women’s accession unconstitutional by a vote of 4:1. The majority of judgements were focused on the principles of moral freedom, equity, and development. Nevertheless, the judges had to ask some seemingly simple questions regarding the existence of the devotees of Lord Ayyappa and to arrive at their conclusions.

To satisfy the jurisprudential tests of the Court, the devotees were forced to prove their denominational status and the essentiality of the impugned practice. There is a long and complex context behind both of these issues, to be discussed in this essay. The case of Sabarimala testifies to the progression of these controversial legal methods, the test of religious affiliation and the test of the basic traditions. Besides, the public response to the case confirms the importance of adjudication of religious freedom in India and reveals the interrelationship between many distinct realms: the political, the legal, and the judiciary.

Throughout the introduction, the facts and circumstances of the Sabarimala case were detailed, and this review would only concern the devotees of Lord Ayyappa ‘s argument to constitute a religious religion. Needless to mention, the Sabarimala case was one of immense public interest. The case further reflects the development of the Court’s jurisprudence on religious sects and its current significance. Justice Ramaswamy, the author of the judgment, also continued to stress the importance of multi-faith institutions in general: “Congregation and assimilation of all parts of society, particularly in the place of worship, provides a sense of fellowship guaranteed in the Preamble of the Constitution and fosters brotherhood for social unity, peace and integration.” In the case of Sabarimala, the respondents had to reconcile the fact that Muslims and Christians are going on a pilgrimage and entering the temple of Sabarimala as adorers. It was submitted, “A distinctive aspect of pilgrimage is the fair inclusion of pilgrims of all faiths in the pilgrimage.

Conclusion

Indian legal jurisprudence developed around two central themes: what constitutes a religious affiliation, and what rituals are necessary for religion. The test of religious identity is used where a party argues that it has abused its freedom to control its religious affairs. There was a period in Indian history when religion supplied, governed, and dominated the country’s legal and judicial system. The case now is quite the reverse. In today’s secular India, it is land law that determines the scope of religion in society, and it is the judiciary that determines what the religion-related laws say, signify, and require.

If it is unclear that the group is a religious denomination, then the Court will examine its characteristics to render a judgment. When religious beliefs clash with the statute, the principle of the important belief is applied. The Court determines how the activities being questioned are important to the religion, and if not, refuses its fundamental security. Religious beliefs and practices tend to influence Indian culture strongly. This religious aspect remains duly reflected in the Constitution and the rapidly increasing body of national legislation. It has also not stayed outside the field of judicial activism seen traditionally in India.

The view adopted by the Supreme Court elucidates the features of Indian secularism not only in philosophy but in reality as well. Through doing so, it helps us to better place India in the broader discourse on transnational secularism and freedom of religion. This research examined how India’s Supreme Court viewed religious freedom and the processes by which it explained its position. In religious cases of various nature and kinds, the judicial decisions of the higher courts generally reflect an attitude of objectivity and impartiality. There were some aberrations, few and far between, pointing at times to the presence of committed judges or those influenced by particular ideologies of religion and politics.

References

- https://ael.eui.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2014/05/Evans-19-Background-Mahmood.pdf

- https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/63259/Williams_hawii_0085O_10158.pdf

- https://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=922005065110002076019064074113013100030050050078068020092085105072067008101010085103029001033127027001029092097080018071025081016039074000002097119015005065024021107058092077003024096026123083103025020109001103069115069125069109106092064127023112022117&EXT=pdf

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications