This article is written by Taha bin Tasneem, Faculty of Law, Aligarh Muslim University.

Table of Contents

Introduction

In the Law of Torts, ‘Remoteness of Damage’ is an interesting topic. The general principle of law requires that once damage is caused by a wrongful act, liabilities have to be assigned. But, as many cases have shown, assigning liabilities is not always a simple task at hand.

Once a wrongful act has been committed (tort), it can have multiple consequences. The consequences can have further consequences. These ‘consequences of consequences’ can become a long chain and at times the problem of the liability of the defendant comes up. The question that this particular topic deals with is “How far can the defendant’s liability be stretched for the ‘consequences of consequences’ of the defendant’s tort?”

To a first-time-reader, this whole concept of ‘consequences of consequences’ would sound confounding. Therefore, in order for us to appreciate the problem better, we may look at a simple example.

In this simple example, we see that the defendant who was a cyclist negligently hits a pedestrian. Incidentally, the pedestrian happened to be carrying a bomb. And due to the negligence of the defendant, the pedestrian falls and the said bomb explodes, resulting in the death of that pedestrian. Now, due to the explosion of the bomb, a nearby building catches fire and five of its residents die. As a result of the fire, the building collapses and nearby structures are destroyed, resulting in 20 more deaths. Further, the destruction of nearby shops results in pecuniary losses to the shop owners.

Although one would tend to easily dismiss this example as too far-fetched, it is not difficult to see that similar cases resembling this particular domino effect can exist and that their existence can create questions of legal importance.

In the above example itself, we can see how a tort of negligence committed by the defendant can result in consequences that were neither intended by the defendant nor comprehended by him beforehand. Such a situation creates question for assigning blame. Even if the Court were of the opinion that the defendant was to be blamed for the death of the pedestrian, would the Court also unhesitatingly place the same amount of the blame on the defendant for the death of the other 25 people?

The problem is also explained by Lord Wright, to some extent, in the case of Liesbosch Dredger v. S.S. Edison:

“The Law cannot take account of everything that follows a wrongful act; it regards some subsequent matters as outside the scope of its selection, because it was infinite of the law to judge the causes of causes, or consequences of consequences. In the varied web of affairs, the law must abstract some consequences as relevant, not perhaps on grounds of pure logic but simply for practical reasons.”

To answer such questions, jurists propose that a defendant should be made responsible only for the consequences which were proximate (and not remote) consequences of the defendant’s wrongful act.

Proximate and Remote Damage

Just as Lord Wright has pointed it out, we have to draw a line for practical purposes. Now, the question that arises is where exactly is this line to be drawn?

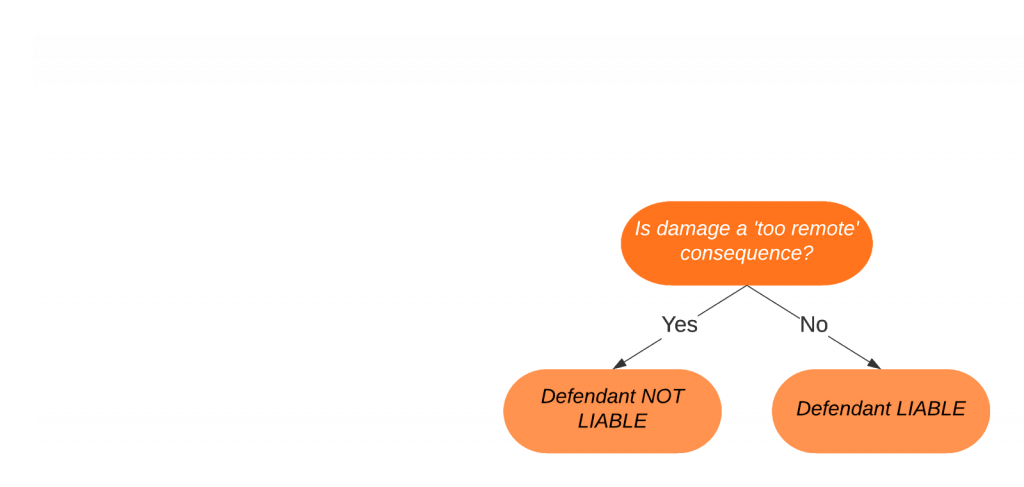

To answer this question, we look at a test known as ‘the test of remoteness’. With this test, we check if the damage is ‘too remote a consequence’ of the wrongful act or not?

Few Illustrations for Proximate and Remote Damage

Scott v. Shepherd (The Squib Case)

In this case, a person A threw a lighted squib into a crowd. The squib fell on a person B. B, in order to prevent injury to himself, threw that squib further. It landed on another person C, who in turn threw it further and it finally exploded on a person D, thereby injuring him. As a result of the explosion, D lost one of his eyes.

In this case, A was held liable to D. Although one would say that his act was ‘the farthest from the injury to D’, his act was held to be a proximate cause of the injury to D.

Haynes v. Harwood

In this historically famous case, the servants of the defendant, owing to their negligence abandoned a horse van on a crowded street. The street had children and women. Some children pelted stones at the horses, as a result of which the horses bolted and started posing a threat to the safety of the people in the street. In order to stop the horses and to rescue the women and children, a policeman (the plaintiff here) suffered injuries himself.

In a lawsuit brought by the plaintiff against the defendant, one defence pleaded was that of novus actus interveniens (remoteness of consequences).

Again, in this case, the Court held that novus actus interveniens was not a valid defence and that the negligent act of the defendant’s servants leaving the horse van unattended as the proximate cause of the injury suffered by the plaintiff.

Lynch v. Nurdin

This case is similar to the previous one to a certain degree. Here, the defendant left his horse-cart unattended on a road. Some children began playing with the said horse-cart. One child sat on the cart (the plaintiff) and another set the horse in motion. Consequently, the child suffered damage and an action was brought.

In this case too the defence of novus actus interveniens was pleaded. But again, it was held by the Court that the injury to the plaintiff was a proximate consequence of the defendant’s act and hence he would be held liable to the plaintiff.

Two Tests of Remoteness

Now that we have seen that the law deems a person liable for the injuries caused which were proximate consequences of that person’s act, one might ask about the parameters on which the Court decides which act is a proximate one and which one remote.

To answer this question, we see two tests of remoteness during the course of legal history:

- Test of reasonable foresight; and

- Test of directness.

Test of Reasonable Foresight

According to this test, if the consequences of a wrongful act could have been foreseen by a reasonable man, they are not too remote.

Pollock was an advocate of this test of remoteness. He opined, in cases Rigby v. Hewitt and Greenland v. Chaplin, that the “liability of the defendant is only for those consequences which could have been foreseen by a reasonable man placed in the circumstances of the wrongdoer.”

But here we must note that it would not be a sufficient defence in itself to say that the defendant did not foresee the consequences. Instead, it would be for the Court to decide, upon the standards of reasonability, whether the consequence should have been foreseen by the defendant or not.

This test of reasonable foresight lost its popularity to the test of directness. But, as we shall see later, it managed to regain currency among jurists.

Test of Directness

According to the test of directness, a person is liable for all the direct consequences of his act, whether he could have foreseen them or not; because consequences which directly follow a wrongful act are not too remote.

Further, according to this test, if the defendant could foresee any damage, he will be liable for all the direct consequences of his wrongful act. To understand this particular test of remoteness better, it would suffice to look at the Re Polemis Case.

Re Polemis and Furness, Wilthy & Co.

This case, popularly referred to as the Re Polemis Case, was the landmark case on the test of directness. The Courts of Appeal held the test of reasonable foresight to be the relevant test whereas later the Privy Council upheld the test of directness.

The relevant facts of the case are that the defendants chartered a ship to carry cargo. The cargo included a quantity of Petrol and/or Benzene in tins. There was a leakage in the tins and some oil was collected in a hold of the ship. Now, owing to the negligence of the defendant’s servants, a plank fell in the hold and consequently sparks were generated. As a result of those sparks, the ship was totally destroyed by fire.

In this case, the Privy Council held the owners of the ship entitled to recover the loss, although such a loss could not have been foreseeably seen by the defendants. It was held that since the fire (and the subsequent destruction of the ship) was a direct consequence of the defendant’s negligence, it was immaterial whether the defendant could have reasonably foreseen it or not. As per Scrutton, L.J.:

“Once an act is negligent, the fact that its exact operation was not foreseen is immaterial.”

Wagon Mound Case: The Re-affirmation of the Test of Reasonable Foresight

The test of directness that was upheld in the Re Polemis case was considered to be incorrect and was rejected by the Privy Council 40 years later in the case of Overseas Tankship (UK) Ltd. v. Morts Dock and Engg. Co. Ltd., also popularly known as the Wagon Mound Case.

The facts of this case are as follows:

The Wagon Mound was a ship which was chartered by the appellants (Overseas Tankship Ltd.). It was taking fuel at a Sydney port at a distance of about 180 metres from the respondent’s wharf. The wharf had some welding operations going on in it. Owing to the negligence of the appellant’s servants, a large quantity of oil was spilt on the sea which also reached the respondent’s wharf. Due to the welding operations going on there, molten metal (from the respondent’s wharf) fell, which ignited the fuel oil and a fire was caused. The fire caused a lot of damage to the respondent’s wharf and equipment.

In this case, the trial court and the Supreme Court held the appellants liable for the damage to respondents based on the ruling in Re Polemis. But when the case reached the Privy Council, it was held that Re Polemis could not be considered good law any further and thus the decision of the Supreme Court was reversed. It was held that the appellants could not have reasonably foreseen the damage to the respondent and therefore were not liable for the damage caused.

In the case Lord Viscound Simonds observed:

“It does not seem consonant with current ideas of justice or morality that, for an act of negligence, … the actor should be liable for all consequences, however unforeseeable.”

They also maintained that “according to the principles of civil liability, a man must be considered to be responsible only for the probable consequences of his act”.

And therefore with this case, the test of reasonable foresight regained its authority to determine the remoteness of damage and subsequently the liability of a person for the damage caused by him in cases of tort.

Wagon Mound Ruling Followed in Subsequent Cases

Hughes v. Lord Advocate

In this case, workers employed by the Post Office left a manhole in the road unattended. Before they left the site, they covered the manhole with a tarpaulin entrance and placed several paraffin lamps around it. The 8-year-old plaintiff, attracted by the lamps, was playing around the manhole along with another child. One of the lamps was knocked down, causing an explosion in the manhole. The explosion resulted in damage to the plaintiff.

In this case, the Court held that even though the explosion was not foreseeable by the servants of the Post Office, the type of the damage (burns) was. Therefore, the defendants were held liable.

Doughty v. Turner Manufacturing Co. Ltd.

In this case, the plaintiff was employed by the defendant. Owing to the negligence of other workmen employed by the defendant, an asbestos cover slipped into a cauldron of molten hot liquid. The resulting explosion caused injury to the plaintiff, who was standing nearby.

It was held that the damage which resulted from the explosion was not such that could have been reasonably foreseen by the defendant, and therefore the defendant’s negligence was not a proximate cause of the damage to the plaintiff. The defendants were held not liable.

S.C.M. (UK) Ltd. v. W.J. Whittall & Sons

The Court of Appeals applied the test of reasonable foreseeability in this case. In this case, due to the defendant’s workers’ negligence, an electric cable was damaged. As a result of this damage, a long power failure followed in the plaintiff typewriter factory. Consequently as a result of this power failure, the plaintiff alleged that there had been a loss of production and damage to his factory’s machines.

The Court in this case held that the defendants were aware of the fact that the said electric cable used to supply power to the plaintiff’s factory, and that they could have reasonably foreseen that any such power failure would lead to significant loss to the plaintiff. And hence, the plaintiff was entitled to damages.

References

Cases

- Liesbosch Dredger v. S.S. Edison [1993] AC 449.

- Scott v. Shepherd [1773] 2 WM B1 892.

- Haynes v. Harwood (1935) 1 K.B. 146.

- Lynch v. Nurdin (1841) 1 Q.B. 29.

- Rigby v. Hewitt (1850) 5 Ex. 240.

- Greenland v. Chaplin (1850) 5 Ex. 243.

- Re Polemis and Furness, Wilthy & Co. (1921) 3 K.B. 560.

- Overseas Tankship (UK) Ltd. v. Morts Dock and Engg. Co. Ltd. (1961) A.C. 388.

- Hughes v. Lord Advocate (1963) AC 837.

- Doughty v. Turner Manufacturing Co. Ltd. (1964) 1 Q.B. 518.

- S.C.M. (UK) Ltd. v. W.J. Whittall & Sons (1971) 1 Q.B. 337.

Books

- R.K. Bangia, Law of Torts (Allahabad Law Agency, Faridabad, 24th edn., 2017).

Websites

- https://www.toppr.com/guides/legal-aptitude/law-of-torts/remoteness-of-damages-law- of-tort/.

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/remoteness-of-damages/.

- www.wikipedia.org.

- https://www.scribd.com/document/432378757/Remoteness-of-Damage-Law-of-Torts- Project.

- https://www.legalbites.in/remoteness-of-damages/.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications

Excellent writing Mr. Taha

Keep up the good work.