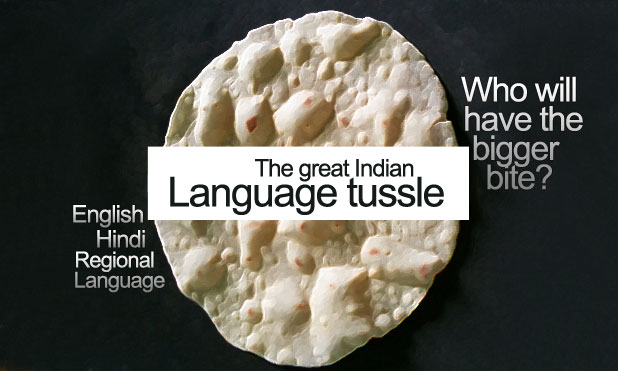

In this Blog post, Abhiraj Thakur, a student of NALSAR University of Law analyses the language policy of India as incorporated in the Official Languages Act of 1963. He further highlights a few shortcomings of the policy.

With a population of over one billion speaking more than a thousand varied languages, India certainly is one of the largest multilingual nations in the world. With their origins in Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, Austro-Asian and Tibeto-Burman language families,[1] the plethora of languages spoken here represent perfectly India’s vast and diverse history. Indian leaders, while making the Constitution planned it thus that Hindi, with the Devanagari script, would be the most prominent language and would promote regional communication and unify the numerous cultures of India. Today, however, English and Hindi both share the same status as official languages.

The write up is a brief analysis of the Official Languages Act of 1963. The objective is to address certain questions about the language policy of India; first, the selection of various languages as ‘official languages’ and second, the prevalence of said languages in the Indian education policy. Finally, the importance of the Official Languages Act, 1963, and the tri-language formula about the Indian language policy is highlighted.

Overview

The Constitution, adopted in 1950, necessitated that English and Hindi be utilized for conducting the Union’s official business for a time of fifteen years [s. 343(2) and 343(3)]. After that time, Hindi should turn into the sole official dialect of the Union. It demonstrated difficult to supplant English with Hindi, in any case, in light of substantive restriction from the southern states, where Dravidian dialects were talked. They felt that the central government was attempting to force the entire nation to use Hindi, including the south, and chose to keep using English, which they thought was more “adequate” on the grounds that, much unlike Hindi, it was not connected with any specific ethnic culture.[2]

The Parliament, in 1963, passed the Official Languages Act, which lawfully settled Hindi and English as the dialects utilized as a part of Congress, while leaving states and domains to pick their own formal languages. In 1976, the Act was changed to formulate the Official Languages Rules, which, too, were revised in 1987.[3]

Summary of the Act

Section 3 of the Official Languages Act negates the 15-year-old lapsed period for the utilization of English. Subsection 3 allows the utilization of both dialects, Hindi and English, in resolutions, general requests, rules, warnings, authoritative or different reports or press discharges issued or made by the central government or by a service, division, office or company claimed or controlled by the central government. Subsection 5 of Section 3 states that until the legislatures of the states that haven’t adopted the English language as the official one pass a resolution for stopping the use of English for the purposes laid down by the Act, the provisions will continue to remain in force.

Section 5 of the states that the Hindi rendition of government acts will be viewed as definitive over the version in English. The Official Languages Act in this way seems to energize the utilization of Hindi over English. Section 6 of the Act unequivocally states that when a language other than Hindi is prescribed by any state assembly for the passed Acts, an identical interpretation in Hindi along with an English interpretation shall be published, and the Hindi version shall be the definitive one.

Under Section 7 of the Official Languages Act, the Governor of a State (except for Jammu and Kashmir) with the past assent of the President, may approve the utilization of Hindi or the official dialect of the State, notwithstanding English for the reasons of any judgment, declaration or request passed or made by the High Court for that State and for any judgment, announcement or request passed or made by in that dialect (other than English).

Themes

The Three Language Formula

The three language formula is a policy that was formulated by the Education Ministry of the Indian government in the 1968 National Policy Resolution.[4] It provides that in all government schools across India, there shall be three languages to be taught: English, as a mandate; Hindi, too, is compulsory, both in Hindi-speaking states and non-Hindi-speaking states; and finally, the third language is the local language of the region where the school is located.

The three language formula has taken multiple forms in India on the basis of states and their own official and local languages.[5] While Hindi and English remain common to all, they change from first language to second and third languages depending on that particular state’s government. For example, while West Bengal’s local dialect Bengali is the closest to Hindi as compared to Malayali or Tamil, the government chose not to teach Hindi at all, as they considered Bengali a much more culturally rich language. In Kerala, however, the learning of Hindi as a language was made compulsory despite the drastic difference between it and the local language.

The basic purpose of the three-language formula was, apart from the overt objective of making widespread the awareness of Hindi and English as national languages, the obscure objective of increasing multilingualism in children across the country. Multilingualism, as has been scientifically proven, not only broadens a child’s horizons but also is conducive to them becoming more creative and more socially tolerant.

Language policy in India

When we talk about the language policy of India, the first thing to be mentioned is the difference between the national language and the official language of a country. While national language refers to the language that is most widely used in cultural, political and in social realms, the official language refers to the language that is used for all of the government’s operations. The official language is pragmatic, wherein the national language is merely symbolic.

Hindi, as it is used today, is thought of as a national language due to its being the only language in use that is not state or region-specific. However, according to the Constitution of India, Hindi is only the official language of India.

Apart from these two partially “official” languages, India’s census records hold that there are 112 languages that are prevalent all over the country. Yet, only 22 of them are a part of the Eighth Schedule, which means that only twenty-four out of a total of a hundred and fourteen dialects are recognised as national languages. Though these 22 languages originate from all the different language families, there are still a number of languages like Bhili which are spoken by the most number of people in India barring Hindi which ought to be included in the list. The only likely reason for Bhili, among other such dialects, to be excluded is political intervention.

Education policy and the language policy

The Indian education system is multilingual in its character every sense of the word. Primary schools in Mumbai run in nine different languages, and those in Karnataka and West Bengal run in eight and fourteen languages respectively.[6] Most states, as was the goal of the education policy makers at the time of Independence, have their aim as developing and strengthening the multilingual characters of the system.

However, there are multiple problems in the implementation of the three-language system. The formula does not refer to either the mother tongue or the home dialect of a student, which are both imperative to the cognitive development of a child. Also, many states have implemented the formula only partially, choosing to take up only two languages as opposed to three, mostly consisting of English and Hindi. The existence of classical languages such as Sanskrit is scarce in most Hindi-speaking states.[7] Though the Eighth Schedule was expanded to include more languages, the educational system regarding languages has remained almost the same.

To conclude we can say the language policy in India is mainly dependent on the Official Language Act, 1963. The Kothari Commission formulated the language policies with the objective of unifying the country’s diverse cultures and dialects via a common ‘official’ language, which, at that point, was Hindi. However, due to failings of the three-language formula and also in the education policy of India in relation to languages, the original aim has morphed into having both English and Hindi as quasi-official languages. From the resistance by numerous states in implementing the said policies to shortcomings in the actual policy, the solution found by the Language Commission was a sort of temporary and remedial measure (allowing the usage of English for ten years) that has been continually extended and used instead of finding a more infallible and constant policy to suit today’s needs and objectives.

Footnotes:

[1] Dravidian languages”. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

[2] “There’s no national language in India: Gujarat High Court”. The Times of India. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

[3] Sisir Kumar; A History of Indian Literature, 500-1399: From Courtly to the Popular, pp.140-141, Sahitya Akademi, 2005, New Delhi.

[4] “Indian Education Commission 1964-66”. PB Works. 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

[5] Introduction to Education Commissions 1964-66″. Krishna Kanta Handiqui State Open University. 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

[6] “Board of Higher Secondary Education”. Board of Higher Secondary Education. 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

[7] “National Policy on Education 1968” (PDF). Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications

[…] Source […]