This article has been written by Johana George, pursuing the Certificate Course in Advanced Civil Litigation from LawSikho.

Table of Contents

Introduction

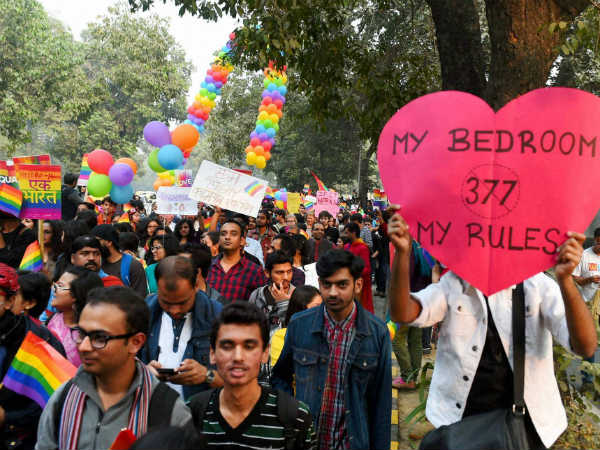

Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India is a celebrated judgment by the Supreme Court of India refining the legal position of homosexuals. The Apex Court, in September 2018, read down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 overruling its earlier decision in Suresh Kumar Koushal. & v. Naz Foundation and recognizing the Fundamental Rights possessed by the homosexual community. The judgment was a moment of celebration for many who had been advocating for equal rights for homosexuals since a coon’s age.

In this article, we will discuss the history of evolution, the mode of Indian conduct in different timelines and the mode of conduct of different courts towards Section 377 and the theories constituted by Navtej Singh Johar case, i.e., constitutional morality, transformative constitutionalism, Right to Privacy, Right to Equality, Right to Dignity, Right to Health, Freedom of Expression.

History of Section 377

In the West, sexual intercourse by same-sex couples was outlawed both in Judaism and Christianity, since the offenses relating to them were decided by the ecclesiastical courts (laws governing the affairs of the Christian Church). As a result of England’s Henry VIII breaking with the Roman Catholic Church, the Buggery Act of 1533 (Section 377) (See here) was introduced prohibiting and criminalizing anal penetration, bestiality, and homosexuality (in a broader sense). Drafted by Thomas Macaulay this law defines ‘buggery’ as an unnatural sexual act against the will of men and God.

As per Macaulay’s original draft, anybody who touched or was touched (with consent) by any person, or any animal intending to gratify unnatural lust, would be penalized and punished with imprisonment of which may extend to 14 years and not be less than 2 years (Article 361). Anyone who touched any person without that person’s free consent, for the same above-said purpose would be penalized and punished with imprisonment extending to life and not be less than 7 years (Article 362).

After several reviews of the draft, the Indian Law Commission concluded the Draft Penal Code to be sufficiently complete. The revised edition was forwarded to the Supreme Court and Sudder Court Judges at Calcutta in 1851 and the Committee of Sir Barnes Peacock finally sent the draft of Section 377 for enactment.

It was only after a long 150 years the deletion of Section 377 was recommended by B. P. Jeevan Reddy, J’s Law Commission Report of 2000 (172nd Report), consequent to the changes made in preceding sections clarifying that anal sex would not be penalized in the presence of consent, regardless of being same-sex or otherwise.

Decisions in Naz Foundation v. Govt. of NCT of Delhi and Suresh Kumar Koushal & Anr. v. Naz Foundation and Ors

The struggles for LGBT rights had already begun outside the courts, with various organizations working to spread awareness about the high incidence of HIV/AIDS amongst LGBT persons and the discrimination faced by HIV/AIDS patients, and due to the stigma attached with Section 377. Though petitions were filed against the Section from the early 1990s, they continued to be dismissed. The first petition was finally heard by the Delhi High Court in 2006 as a matter of public interest which led to the landmark Naz Foundation case.

Naz Foundation v. Govt. Of NCT of Delhi

The Naz Foundation India, an NGO which was committed to HIV/AIDS prevention and intervention, filed a Public Interest Litigation in the High Court of Delhi challenging the constitutionality of Section 377. The petitioner therein submitted that Section 377 encouraged discriminatory attitudes, abuse, and harassment of the LGBT community, which had thus impaired HIV/AIDS prevention efforts and access to treatment. The Court thus held that Section 377 was unconstitutional.

Some of the important findings of the Court include:

- The Indian Constitution expresses this value of inclusiveness ingrained in Indian society. The High Court held that a certain category perceived to be deviants or different by the majority need not be excluded or ostracised. Only then can the LGBT persons be assured of a life of dignity without discrimination.

- Discrimination is the antithesis of equality and it is this recognition of equality that raises the dignity of every individual. The Constitution does not permit any statutory criminal law to captivate the community based on some popular misconceptions on who they are.

- It was found out that Section 377 violated the Right to Dignity and Privacy promised by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the European Court of Human Rights, and the Francis Coralie Mullin case.

- The High Court thus declared Section 377 IPC is in violation of Articles 14, 15, 19, and 21 of the Constitution in so far as it criminalizes consensual and private sexual acts of adults; at the same time, for penile non-vaginal sex (non-consensual) and penile non-vaginal sex involving minors, Section 377 was still valid.

Suresh Kumar Koushal. v. Naz Foundation

The decision in the Naz Foundation was appealed to the Supreme Court attracting a large number of interveners including organizations and individuals who stated that they had an interest in protecting the moral, cultural, and religious values of Indian society.

Court’s findings were:

- Section 377 IPC is applied irrespective of age and consent; It does not criminalize particular people, identity or orientation and only identifies certain acts which would constitute an offense. So, the prohibition under Section 377 was to regulate sexual conduct regardless of gender identity or orientation.

- The argument that Section 377 had become a tool to perpetrate harassment, blackmail, and torture onto the LGBT community was denied by stating that such a treatment is neither mandated nor condoned by the Section and the mere misuse by police authorities and others cannot hold for unconstitutionality.

- The ones who indulge in carnal intercourse in the ordinary course and those who indulge against the order of nature constitute 2 different classes. The latter category cannot claim that Section 377 suffers from irrational classification.

- Only a minuscule fraction of the Indian population constitutes the LGBT community and in the last 150 years, less than 200 persons have only been prosecuted under Section 377 because of which Section 377 IPC cannot be held ultra vires the provisions of Articles 14, 15, 19 and 21 of the Indian Constitution.

Case background

While the curative petition of the Naz Foundation was pending, the Supreme Court in K.S. Puttaswamy v. UOI confirmed the right to privacy to be a fundamental right under Article 21. Following the celebrated case, a writ petition was filed in 2016 by five celebrity petitioners, Bharatnatyam dancer Navtej Singh Johar, journalist Sunil Mehra, hoteliers Aman Nath and Keshav Suri, and celebrity chef Ritu Dalmia challenging the constitutionality of Section 377 and seeking the rights of sexual autonomy. Some of their major contentions and submissions included:

- Fundamental rights should be available to the LGBT community regardless of being a minority.

- Section 377 is wholly arbitrary and vague with an unlawful objective; it is hence discriminatory under Article.

- Section 377 penalizes on the basis of a person’s sexual orientation, and hence in violation of Article 15.

- Section 377 deprives the LGBT community of the sexual expression of and thus has a ‘chilling effect’ on Article 19(1)(a).

- Section 377 violates Article 21 which encompasses all aspects of the right to life and liberty including the right to privacy, the right to autonomy, the right to live with dignity, and the right of self-determination.

- There is no intelligible differentia between a natural and unnatural sexual act as per Section 377 allowing broad and senseless interpretation

Whereas the submissions of the Respondent included:

- There is no absolute right to privacy.

- The offensive acts proscribed by Section 377 IPC are derogatory to constitutional dignity.

- Issues relating to the legal rights of the LGBT community, their gender identity, and sexual orientation were exhaustively considered the various provisions of the Constitution, and, accordingly, reliefs were granted by the Supreme Court in NALSA.

- People indulging in unnatural sexual acts are more vulnerable to HIV/AIDS

- If Section 377 is declared unconstitutional, the Indian family system and the institution of marriage will be shattered.

- Decriminalizing Section 377 would be against Indian religions. Thus, while deciding its unconstitutionality, Article 25 needs to be considered.

- Decriminalizing Section 377 would render the forced acts under the section remediless.

- When Section 377 IPC is decriminalized, a married woman would be remediless against the sexual acts between her husband and his male partner.

- The interests of a citizen/section of society are secondary to the public interest.

- The Yogyakarta principles have limited sanctity as it is not a binding international treaty.

Despite the above-said contentions, the respondent, i.e., the Union of India left the question of the constitutionality to the wisdom of the court to the extent that it applies to ‘consensual acts of adults in private.

The issues raised before the court were:

- Whether the reasoning in Suresh Koushal’s judgment is proper or not?

- Whether Section 377 permitting the discrimination of the LGBT community on the basis of “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” violate Articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution?

- Whether criminalization of gender expression has a ‘chilling effect’ on Article 19 (1) (a) of the LGBT community?

- Whether Section 377 violates the Right to Autonomy and Right to Dignity as under Article 21 by penalizing private consensual acts between same-sex?

Transformative constitutionalism

Our Constitution is a great social and revolutionary document, aiming at the transformation of medieval Indian society into an egalitarian democracy. Our courts have time and again realized that in a society undergoing rapid socio-economic changes, a static judicial interpretation of the Constitution would only impede its spirit, i.e., our Constitution must have the ability to change and adapt to the changes brought in the society. This forms the concept of transformative constitutionalism.

Our Indian society has been in continuous progressive change for a long time. The sexual minorities were accepted and given space after the NALSA v. Union of India judgment. But the carnal intercourse between same-sex people was still punishable under Section 377 IPC, creating a chilling effect on the freedom of sexual expression. The question of freedom of choice of partner is also found in many recent judgments wherein the Court held that a person who has acquired a certain age and capability has the right to choose his/her life partner.

The court held in Shafin Jahan that the expression of choice in accord with the law is the acceptance of individual identity. Curtailment of such an expression based on conceptual social values will destroy individuality. Societal morals can have their space but they can never be above the constitutionally guaranteed freedom. It has been so long a period for the LGBT community that it can’t suffer the indignities of denial any more. By criminalizing the consensual sexual acts between the same sexes, the constitutional guaranteed liberty and equality is denied. Dissension that usually comes in the way is that the permissible sexual activity between two adults is different when the case is that of two individuals having the same sex. The ground of claim raised is the so-called social standardization. Such an assertion ignores the natural individual orientation and the right to a dignified life.

Constitutional morality

Constitutional morality is what is inherent from the norms and the conscience of the Constitution and any act established must be in harmony with the constitutional terms in order to be justified. It is this test of constitutional justness that falls within the sweep of constitutional morality.

The 3 organs of the State have always been urged to maintain a heterogeneous fiber in the society and curb majoritarianism. Any attempts to shove a homogeneous, and uniform philosophy throughout the society will thus be against the principle of constitutional morality. Constitutional morality cannot be equated with the popular opinion of the period. If the whole society or even a part of it aspires or prefers anything different for themselves, they are perfectly fit to have that freedom to be different, provided that it remains within the legal framework and must be provided an environment to sustain, if not fostered. The courts have to thus be guided by the principle of constitutional morality rather than societal morality.

It is pertinent to mention here that the founding fathers of the Constitution had adopted an inclusive Constitution with provisions that allowed and sometimes directed the State to undertake actions to eradicate the discrimination of the backward and vulnerable sections of the society by the so-called upper caste prior to the establishment of the Constituent Assembly.

Right to privacy, dignity, and health

When a biological expression is hindered through the imposition of law, an individual’s natural and constitutional right is eroded. Here is where the essence of dignity speaks up and where we, as our constitutional duty, should allow an individual to behave, conduct, and express himself/herself as he/she desires. When it comes to the national sphere, dignity is often considered as an important aspect of Article 21 of the Constitution whereas internationally, it was identified as a basic right after the institution of the UDHR (Universal Declaration of Human Rights).

After the Puttaswamy judgment, the challenges against Section 377 IPC have been stronger than ever. In the said decision, the Bench held that sexual orientation is a facet of the right to privacy which is in itself a fundamental right under the Constitution of India. Individual autonomy has a significant space in the compartment of privacy and is expressive of self-determination which further includes sexual orientation and identity. These, as under the constitutional scheme, do not accept any interference as long as it is not against decency or morality (constitutional morality). Under the autonomy principle, an individual has sovereignty over his/her body. Anybody can surrender it to another and their intimacy is a matter of choice.

Chandrachud, J., one of the judges who spoke for the majority in the Puttaswamy case, regarded that the reasons stated in Suresh Koushal’s judgment cannot be a valid constitutional basis for disregarding the right to privacy. He further observed that the rationale in Suresh Koushal i.e., only a small fraction of the Indian population is LGBTQ community, is not a proper basis to deny the right to privacy. Whatever the percentage may be, what matters is whether the community is entitled to the claimed fundamental rights and whether those rights are violated due to the existence of any statutory law. When the answer is in the affirmative, the courts must not hesitate to strike them down.

The above-mentioned view is also cemented by a landmark Supreme Court judgment wherein the Court was concerned with the fundamental rights of the arrested, which forms a minute fraction of the total population. A recent case in which the Supreme Court protected the fundamental right to die with dignity was the Common Cause wherein it protected the rights of those some who slipped into a permanent vegetative state (again a very small fraction of the society).

Just like the right to privacy, an individual has the right to the union under our Constitution. The phrase ‘union’ does not solely mean marriage, but companionship in a physical, mental, sexual, and emotional sense. In the present case, the LGBT community was seeking the realization of this cardinal right to companionship.

The right to health and healthcare access is one of the other facets of the right to life. The LGBTQ persons are usually at a higher risk of HIV than heterosexuals because of the lack of safe spaces to engage in sex. They are thereafter inhibited from seeking medical help for they are under the threat of being ‘exposed’ and as a result be prosecuted. In an international case, Nicholas Toonen v. Australia, it was stated that the statutes criminalizing homosexual activity impeded public health programs and it was a proportionate measure hindering the aim of preventing the spread. Its criminalization would thus counter the implementation of education programs for the prevention of HIV/AIDS.

Although the LGBT community learns to cope up with the stigma against them, the pattern of prejudice causes psychological distress, especially when they conceal or deny their identity. It is pertinent to mention here that the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 provides for the right to access mental healthcare equally, without any discrimination, in line with “sexual orientation”. In other words, Section 377 criminalizes LGBT, which then inhibits them from access of healthcare facilities, while the Mental Healthcare Act provides them the right to access mental healthcare without discrimination, even on the basis of ‘sexual orientation’.

Comparative analysis of sections 375 and 377 of IPC

Section 377 of IPC, 1860 uses ‘whoever’ and is thus a gender-neutral one. The word ‘carnal’, means ‘of the body’ and ‘sexual intercourse’ means the contact between a male and a female‘s sexual organs. But the ‘order of nature, another expression used in the section, is neither defined in it nor in any other provision of IPC. The ground on which Section 377 IPC penalizes carnal intercourse is that it is against the order of nature. So, what does ‘against the order of nature’ mean?

In Lakhi Sahu (Kanu) v. Emperor, the issue that arose was whether coitus per os amounts to carnal intercourse against the order of nature. There, the Court ruled in affirmative reasoning that the object of intercourse is conception but it was impossible in coitus per os. With the evolution of the society, procreation of children is not the only reason for people to have live-in relationships, or perform coitus. In the contemporary world when even marriage cannot be equated to procreation, the question is whether carnal intercourse between consenting adults of same-sex can be labeled as ‘against the order of nature. Obviously, it is their choice to engage in sex for procreation or otherwise and sex, if performed differently, does not per se be against the order of nature.

On scrutinizing the 7 descriptions of Section 375 IPC and Explanation 2, it can be found that the absence of wilful consent is sine qua non to conclude that the acts in the former part of Section 375 IPC as rape. The major difference between the language of Section 375 and 377 is that the element of consent is absent in Section 377 IPC. It is the absence of wilful and informed consent which makes the offense of rape criminal. On the other hand, Section 377 IPC contains no such exceptions criminalizing voluntary carnal intercourse between homosexuals and heterosexuals.

The litmus test for the survival of section 377

Article 14

Article 14 propounds that equals must be treated equally. In the Budhan Choudhry case, the Court observed that Article 14 forbids class legislation, but it doesn’t rule out reasonable classification for legislation. To pass this test of classification, 2 conditions need to be fulfilled,

- The classification must distinguish between the grouped ones from the left out (intelligible differentia); and

- The object to be achieved by the statute in question must be rationally related to intelligible differentia

377 IPC classifies and penalizes persons who indulge in carnal intercourse aiming at the protection of women and children. But the non-consensual acts criminalized by Section 377 IPC are already meant as penal offenses under Section 375 IPC and the POCSO Act. Per contra, the presence of this Section has resulted in an objectionable effect whereby ‘consensual acts’, which are not harmful to children or women and are performed by the LGBTs owing to their inherent characteristics defined by their identity and individuality. This discrimination meted out to the LGBT is unconstitutional, being in violation of Article 14 of the Constitution, due to the absence of reasonable nexus.

Another point to be urged here is that when Section 377 criminalizes the consensual sexual acts between homosexual adults in private space (which are not contagious to our society), it fails to distinguish between consensual and non-consensual sexual acts, which again shows the absence of reasonable nexus.

Article 19

In the Chintaman Rao case, the Court opined that the phrase ‘reasonable restriction’, which connotes the limitations imposed on an individual’s enjoyment of a right, should not be beyond the public interest. The legislation which excessively invades the individual right lacks reasonableness unless it has an adequate balance between the freedom guaranteed under Article 19(1) (g) and 19(6). The Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India had struck down Section 66A of the IT Act on the ground of over-breadth as it took protected speech and innocent speech within its sweep which further had a chilling effect on free speech.

In our case, it was held that any display of affection amongst the LGBT members in the public cannot be halted by majority perception as long as it doesn’t amount to indecency or disturb the public order. In view of the test, Section 377 IPC does not meet the proportionality criteria and is thus in violation of Article 15 which included the right to choice of a sexual partner. Section 377 IPC is also the weapon of the majority to exploit the LGBT community.

However, if anyone engages in any sexual activity with an animal or engages in sexual activity with another without consent, the said aspect of Section 377 IPC was decided to be still constitutional, inviting penal liability.

Article 21

Bhagwati J. observed in Francis Coralie Mullin’s case that the right to life includes the right to carry on such activities as required as to constitute one’s self-expression. Every act which impairs human dignity will deprive one’s right to life and whether or not it is in accordance with the reasonable, and fair procedure established by law is the test here. It was thereafter re-affirmed by the Constitution bench decision in K.S. Puttaswamy & Anr. v. Union of India & Ors. and Common Cause v. Union of India & Anr. Section 377, since it trims the personal liberty of LGBT persons to engage in consensual sexual activities with a partner of their choice, is in violation of Article 21. The section inhibits them from entering into sexual relationships as a result of which they are forced to lead a solitary life or a closeted life as non-apprehended felons.

The final decision

- Our Constitution is a living, organic document capable of expanding with the changing requirements and demands of society. The Courts must make sure that when the rights of a separate class of persons or even a minority group is not affected and that their basic rights are conserved.

- The primary objective of constitutional democracy is the progressive and inclusive transformation of society.

- The concept of constitutional morality is laid on diversity and it urges the State to preserve the society’s heterogeneous nature curbing any attempts by the majority to usurp the rights of minorities.

- The right to live with dignity is a human right without which every other right would be meaningless.

- An individual cannot exert any control over who he/she gets attracted to. Any discrimination based on one‘s sexual orientation would bring about a violation of the freedom of expression.

- The framers of our Constitution would have never intended that the fundamental rights should be extended only for majoritarian benefit and the reasoning in Suresh Koushal is thus, fallacious.

- A fair examination of Section 377 IPC reveals that the classification adopted has no reasonable nexus as other provisions of the Code (Section 375 IPC) and the POCSO Act already penalizes carnal intercourse in the absence of consent, thus violating Article 14.

- Section 377 IPC fails to make distinguish between non-consensual and consensual sexual acts again implying the lack of reasonable nexus.

- A fair examination of Section 377 IPC shows that it amounts to an unreasonable restriction, and social morality cannot be accepted as a reasonable ground for curbing the fundamental rights of the LGBTQ community, thus violating Article 19(1) (a) of the Constitution.

- The decision in Suresh Koushal is thus overruled.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of India in the case of Navtej Singh Johar undoubtedly took a bold step towards a legal system enforcing the equalitarian values of the Indian Constitution. It endeavors to change the societal beliefs and the status quo by virtue of transformative constitutionalism upholding constitutional morality above the societal morality of the majority. History owes them an apology for the delayed redress for the ignominy and ostracism that they have been suffering. However, the question which remains is whether mere decriminalization of homosexual conduct can transform society? If the societal transformation was the purpose of this judgment, it can only be considered as a baby step towards enhancing the fate of our homosexual community. The law and government must take positive steps to achieve equal protection and equal opportunities in all its manifestations. Nariman J. concluded his opinion by directing the Union to take all necessary measures to publicize the judgment and thus eliminate the stigma faced by the LGBT community in society. He also asked the government and police officials to ensure favorable treatment.

References

- https://www.equalrightstrust.org/ertdocumentbank/Case%20Summary%20Suresh%20Kumar%20Koushal%20and%20another%20v%20NAZ%20Foundation%20and%20others.pdf.

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/case-comment-navtej-singh-johar-v-union-india/.

- http://nujslawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/12-3-4-Chaudhary.pdf.

- http://rsrr.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/RSRR-Vol-5-Issue-1-FINAL3-74-84.pdf.

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals, and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications