‘Anna’esthetic for the democratically ‘Anna’emic?

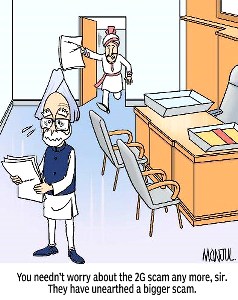

Corruption among government officials is undoubtedly one of the most grave and pervasive threats that can be posed to the fabric of any nation. It is thus scarcely any surprise that almost every form of media in India is at present covering the popular debate and controversy regarding the ubiquitous Lokpal Bill (Government of India’s version) and the Jan Lokpal Bill (as proposed by Anna Hazare), both of which seeks to address the problem of corruption within the governing machinery in the country.

None of these bills, however, is the Indian legislature’s first attempt to combat corruption in public sphere. That honor goes to the Prevention of Corruption Act (POCA), the latest version of which had come into force in India as far back as 1988. Perhaps setting aside for a while the debate about whether the popular agitation and demonstrations are undermining the democratic machinery, the time has come to have a look at these laws and possible future laws and see how they differ from each other in terms of substantive and procedural merits.

The POCA, among other things, identify a series of offences punishable under itself, including a public servant taking gratification other than legal remuneration in respect of an official act, taking gratification to influence public servant or for exercise of personal influence with public servant, criminal misconduct or attempts thereto by public servants etc. In order to try such offences, the Act envisaged appointment of special judges (a qualified Sessions Judge or Additional Sessions Judge or Assistant Sessions Judge) by the Central or State governments. Such special judges had a wide range of powers, starting from taking cognizance of a case (taking notice that a problem/dispute exists and allowing proceedings to begin) without the accused being brought forth for trial, to issuing pardons in exchange of information, to conducting summary trials (a shorter and less time-consuming version of actual trials) under certain circumstances.

However, the POCA suffered from a list of shortcomings, which probably explains an abysmally low rate of convictions under this Act since it has come into being. After all, it is not as if that the Indian public sector has been magically shorn of all corrupt practices following POCA’s arrival! Apart from high-ranking police officers (like Assistant Commissioner or Deputy Superintendent), few other policemen are allowed to investigate an offence under this Act without the order of a Metropolitan Magistrate or a Magistrate of the first class. Moreover, under this Act, prior governmental sanction is required before the court can take cognizance of an offence allegedly committed by an office-holder within the Union or the State governmental machineries, which, pragmatically speaking, is seldom forthcoming.

These problems with the POCA had made it necessary to adopt a new stance in the combat against corruption, which was the reason the Lokpal Bill had been conceived of in the first place. Instead of simply relying on the ordinary law enforcement authority and judiciary to effectively investigate and adjudicate allegations of corruption against government officials by wading through a mountain of ‘red-tapism’ and procedural barriers like the ones mentioned above, an independent institutional framework was conceived of as a specialist in anti-corruption measures.

This would happen by way of having Lokpal in the central level and a Lokayukta in the state level, who will have the power and independence to investigate and prosecute cases of corruption. Creating a one-stop window for addressing corruption problems, allowing individual citizens to directly approach the Lokpal’s office with his grievances, expedited investigation and adjudication of offences of corruption allegedly committed by the government officials as well as the judiciary without need for approval from any higher authority and providing protection to whistleblowers are a few novel features of the Lokpal system.

Having said that, the Government’s version of the Lokpal Bill (LB) and the Jan Lokpal Bill (JLB), as proposed by Anna Hazare and his team do sport a few considerable differences in terms of their provisions, which have been indicated as follows:

JLB includes sitting Prime Ministers, judges, Parliament members’ actions on voting/speech (that couldn’t be questioned before because of Article 105 of Constitution of India) and all government officials within its investigating ambit, unlike LB, but does not include personnel of NGO-s receiving public funds, which LB does.

LB prescribes 8 members other than the Chairperson of whom 4 have to be members of judiciary. JLB prescribes 10 members of whom 4 need to have legal background and a Chairperson to have extensive legal knowledge.

The composition of the selection committee appointing the LokPal also differs between the 2 bills. LB includes the Speaker, a Union Cabinet Minister nominated by the PM, Leader of Opposition in the Rajya Sabha, an eminent jurist and a person having experience in anti-corruption and administrative measures, whom JLB doesn’t include. On the other hand, JLB keeps in the Chief Election Commissioner, the Comptroller & Auditor General, and all previous chairpersons of the Lokpal, whom LB doesn’t refer to.

Regarding qualification of the Lokpal members, LB requires the Chairperson to be the present or an erstwhile Chief Justice of India or Supreme Court judge and the other judicial members to be present or erstwhile Supreme Court judges or Chief Justices of High Courts. Non-judicial members have to have impeccable integrity with minimum 25 years of experience in anti-corruption policy, public administration, vigilance and finance. No member can subsequently become an MP, MLA or be connected with a political party, business or practice a profession. JLB, on the other hand, requires a judicial member to have held office for 10 years or been an advocate of the High Court or Supreme Court for minimum 15 years. All members are required to have impeccable integrity with record of public service, especially regarding anti-corruption. Membership can’t be granted if a person not an Indian citizen, or has a case involving moral turpitude framed against him by a court, or is below 45 years, or was a government servant within the last 2 years.

Regarding the removal process, LB allows President to initiate action followed by a Supreme Court inquiry and remove a member on grounds of biasness, among others. JLB requires Supreme Court’s recommendation, no initiation by the President and an independent complaints authority for investigation.

Among other differences, JLB’s recommendation to bring the CBI under Lokpal’s aegis and for Lokpal to have the power to receive complaints from whistleblowers, recommend cancellation/modification of a lease or licence or blacklist a company and to approve interception and monitoring of communication seem to be noteworthy.

Thus, it is quite clear that POCA’s shortcomings indeed required something more in what promises to be a never-ending battle against corruption in public sphere (although some say simply removing POCA’s requirement of prior government approval for investigating allegations of corruption can be a viable solution). As to the question whether the government’s Lokpal Bill succeeds to be that plausible alternative, or whether the popular mass movement and agitations of Anna Hazare and his followers in and outside Civil Society allow the Jan Lokpal Bill to triumph over the government’s version, one can at best wait and watch events to unfold and which form of democracy and constitutionalism emerges victorious in this struggle fast assuming epic proportions.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications

Visit these spiritual and touching website.

http://anna-hazare-lokpal-bill.in/

It will provide you all current information, live & ongoing for anna-hazare & lokpal-bil

At least we can support him instead of sitting idle.

Like http://anna-hazare-lokpal-bill.in/ website to support anna-hazare!!!