This article was written by Oishika Banerji and further updated by Shefali Chitkara. This article provides a detailed discussion of the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937. It starts with the historical background and the need for such a personal law. The article also highlights a few of the landmark judgements under this Act. Further, the conflict between maintenance and succession under Indian secular law and Muslim personal law has also been discussed.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The partition of India in 1947 not only divided India into two independent sovereigns but also changed the laws applicable to India entirely. Before the 1947 partition, the subject matter of inheritance, succession, marriage, divorce, family relationships, and dower were regulated under the able guidance of the religious laws whose roots existed in the age-old customs. Such laws were often subjected to alteration by various legislations due to the underlying ideologies framing such kinds of laws. The reason behind the promulgation of the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937, was to erase the customary exercises existing with regards to Muslims. Previously, this Act was not applicable in the North-West Frontier Province (which was a province of British India from 1901 to 1947, now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, a part of Pakistan since 2010), as they had their own legislation with divergent traits named the NWFP Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1935. But as of now, the Act of 1937 extends to the whole of India, as has been provided under Section 1(2) of the Act, and is applicable to the whole of the Muslim community.

The Shariat Act, which is officially known as the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937, is a significant law in India. This was enacted by the British colonial government, and its primary objective was to ensure that the application of Islamic law (Sharia) was uniformly practised among Muslims in matters of personal law. Before the enactment of this law, various customary laws often influenced personal matters like marriage, divorce, inheritance, and family relations among Muslims, leading to inconsistencies and perceived injustices. The Act specifically aimed at abolishing these customary practices and replacing them with Islamic principles as outlined in the Quran and Hadith. This would protect the religious rights of Muslims and provide a coherent legal framework for personal matters. The Shariat Act is applicable to all Indian Muslims and emphasises the use of Islamic jurisprudence in legal proceedings involving marriage, dissolution of marriage, maintenance, gifts, and inheritance.

While the Shariat Act was a step towards preserving religious identity and ensuring legal uniformity, it has also sparked debates on gender equality and the need for a uniform civil code in India. Critics argue that some aspects of Shariat law, as applied through this Act, may not align with contemporary views on women’s rights and social justice.

Historical background of the law

Muslim personal law can be traced back to the use of Hidayah, which was used to be consulted by the British courts during the colonial era. Hidayah was referred to during such a period, which was written by Mirghayani, who was a Hanafi scholar, and the same was translated into English by Hamilton. This Hanafi law was used since the Mughals ruled before the Britishers, who were Hanafis. Subsequently, even the British followed the law, which was based on Hidayah, later known as Anglo-Mohammedan Law and now known as Muslim Personal Law or the “Shariat Law”. The Shariat Law kept evolving over a period of time as the writings in the Quran kept developing in response to the issues faced by the Prophet and the community at large.

Modern Islamic nations have applied Shariat law as per the social and political needs within their systems. We have four schools of Islamic law: Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi, and Hanbali, and each of them interprets the writings of the Quran differently.

Origin of the law

Earlier, there was a tribal social structure even before the Islamic religion, and this tribe created laws and rules that were developed with time and as per the evolving needs of society. The Muslim community was established in the 7th century in Medina and spread across various regions. The establishment of Islam, which was translated to “the will of God” as per the Quran, superseded those tribal customs. All the writings of the Quran and also the unwritten customs, known as Shariat, were responsible for governing Islamic society.

The Muslim Personal Law, now also called ‘Shariat Law’, has its origins in the early Islamic period and is taken from the Quran, the Hadith (which means traditions of the Prophet Muhammad), Ijma (which means consensus of Islamic scholars), and Qiyas (which means analogical reasoning). These sources mark the foundation of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), which governs various aspects of a Muslim’s life, including marriage, divorce, inheritance, and family relations.

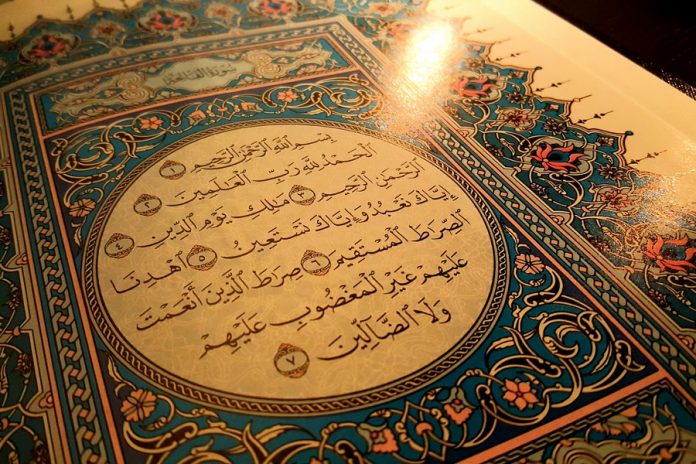

Quran

The Quran, which is considered the literal word of God as disclosed to Prophet Muhammad, is the primary source of Muslim personal law. It enlists a few principles and specific directives on personal matters. For instance, the Quran outlines the rights and duties of spouses, inheritance rules, and the treatment of orphans and children.

Hadith

The Hadith consists of the words, actions, and approvals of Prophet Muhammad, serving as a supplementary source to the Quran. It offers practical examples of how the Prophet implemented the Quranic principles in daily life, thus providing a concrete basis for legal rulings. For example, the Hadith elaborates on the procedures for marriage and divorce, which are only briefly mentioned in the Quran.

Ijma and Qiyas

Ijma represents the consensus of Islamic scholars on certain issues that are not mentioned in the Quran or Hadith. This consensus is crucial for adapting Islamic law to changing circumstances and ensuring its relevance across different regions. Qiyas, on the other hand, is the process of analogical reasoning used to derive legal rulings for new situations in consonance with already established principles already found in the Quran and Hadith.

Overall, the origin and development of Muslim personal law are rooted in the foundational texts of Islam and have evolved through centuries of scholarly interpretation and cultural adaptation, making it a dynamic and living body of law. The advent of Islam in India began with the Arab traders in the 7th century and was solidified through the conquests and establishment of Muslim dynasties, most notably the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526) and the Mughal Empire (1526-1857).

The British codified Muslim Personal Law to streamline its application. The most notable amongst these was the present Shariat Application Act of 1937, which aimed to ensure that Muslims in India follow the Islamic laws in personal matters rather than local customs. This Act marked a significant moment in the formal recognition and codification of Muslim personal law in India, providing a uniform framework for Muslims across the country. After India gained independence in 1947, the Indian Constitution guaranteed the right to religious freedom and allowed different communities to be governed by their own personal laws. Article 44 of the Indian Constitution envisions a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) for all citizens, but it was included within the Constitution as a Directive Principle of State Policy and is not enforceable, and this remains a debatable issue. Consequently, Muslim personal law continues to govern Muslims in personal matters, with various reforms and interpretations over the years.

Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937

This Act of 1937 is not a voluminous Act; it has only a few sections. Every provision has its own importance, and an analysis of each of these sections is necessary for understanding the Act in a better manner. Earlier, there were six provisions; however, Section 5, which talked about the “dissolution of marriage by court in certain circumstances,” was repealed after the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939, which came into force on 17th March, 1939.

The sections of the Act are provided as follows:

- Section 1, which talks about the short heading and scope.

- Section 2, which covers the personal law application to the Muslim community.

- Section 3 talks about the power to create a declaration.

- Section 4 mentions the power of making rules.

- Section 6 enlists the provisions of some Acts that have been repealed.

Title and extent of the Act

As per Section 1(1) of the Act, the short title given to the Act is “Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937,” which was enacted on 7th October, 1937. It extends to the whole of India, and there are no exceptions to the same, as per Section 1(2) of the Act.

Application of the Act

Section 2 of the Act of 1937 mentions the personal law application to the Muslim community. This section highlights ten subjects within its ambit, which are

- “Intestate succession,

- Dissolution of marriage, which includes every kind of divorce, namely talaq, illa, zihar, lian, khula, and mubarat,

- Maintenance,

- Dower,

- The special property belonging to the females,

- Marriage,

- Guardianship,

- Gift,

- Trust, and its associated properties; and

- Wakf”.

For interpreting this Section, two important statements written in this Section need to be seen, which are as follows:

- “Notwithstanding any customs or usage to the contrary”, and

- “Shall be the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat)”.

These two statements are complementary to each other, and one loses its meaning in the absence of the other. It calls for a harmonious construction between the prevalent custom and the law of the land, which has been adopted by this law to give importance to both of them. Before highlighting the aim of this Section, it is important to discuss the reason behind the enactment of such a Section in the Act. As already discussed, the underlying principle of this Act is the elimination of the governing role of religious and customary laws by means of legislative enactments to avoid an increase in discriminatory laws. This Act aimed at achieving such goals. Section 2 provides for this reason behind the formulation of the Act and mandates the application of the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) to the Muslim community. This mandatory nature binds the Indian courts to refer only Muslim law if any dispute arises in the subject matter provided under this Section. Also, Section 2 does not include “adoption, legacies, and wills,” and the courts are not bound to apply Muslim law in these cases.

However, this Section has its own loophole, which is mentioned in the provision itself. Section 2 specifically excludes agricultural land from its ambit, thereby reinforcing the inheritance customs that excluded females from being given the inherited agricultural land, and this shows that women are continuing to be deprived of their legitimate share of agricultural lands as was mentioned under the Islamic Law. The female heirs remained shadowed, and the male heirs continued enjoying their inherited share of agricultural land. This exclusion from the overall scope of the Act has created a barrier within the Act from achieving its objective. Thus, the replacement of customs with legislative enactments has no role to play since the major purpose of the Act has been nullified or its ambit has been restricted.

Declaration making power

Section 3 of the Act mentions the power to make a declaration regarding the desirability of a Muslim individual to be governed by this law. In order to utilise this power, three conditions should be satisfied as provided under this section, which are as follows:

- An individual should be a Muslim,

- He should be competent (as per Section 11 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872) for entering into a contract; and

- He should be an Indian resident.

All the above-mentioned conditions have to be fulfilled for exercising the power given under Section 3 of the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937. As we know who can avail of the power, it is now crucial to understand the consequences of using it. This Section acts as a tool for ensuring the mobility of the previous Section, i.e., Section 2 of this Act. It provides that an individual, after fulfilling the conditions of the provision, can declare his desire to take advantage of the provision, followed by Section 2, which will be applicable to the declarant of such benefit along with all his minor children and their descendants.

Section 3 of the Act includes a few subjects that Section 2 did not talk about. They include “wills, legacies, and adoption”. The provision provides discretion to the courts to apply Muslim law in such areas only if any Muslim individual wants to be governed by the provisions of the Act of 1937 as for the remaining ten subjects given under Section 2 of the Act. A Muslim has to make such a declaration in a prescribed form before the prescribed authority and will be governed by the procedure given under Section 3(2) and Section 4 of the Act of 1937. As Section 3 provides the power to make a declaration to a Muslim person to be governed by the Muslim Law, in the absence of such a declaration, this provision gives an indirect power to the courts to not be bound by such a law while dealing with any matter in dispute under Sections 2 and 3.

Power of the State Governments to make rules under the Act

This Section gives the power to make rules according to the provisions and the objective of the Act to the State governments.

This provision, along with the above-discussed provision of Section 3 of the Act, governs the procedure to be followed by a Muslim to make a declaration as per Section 3(1). The state governments have the power to decide about the prescribing authority and the fees that have to be paid before such authority can be granted for the filing of declarations. It is to be noted that the Act is a central law, and at the time of its enactment, it could not be made specifically for the States. Thus, this Act is flexible enough to incorporate the rule-making power of the state government as per the needs of the Muslims of that particular state, but not by defeating the purpose of this Act.

Repeals under the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937

Section 6 mentions that “certain provisions of a few statutes that appear to be inconsistent with the provisions of the Shariat Act of 1937 have been repealed”. These below-mentioned Acts gave authority to the courts in India for implementing Muslim law before the Shariat Act, 1937, was enacted. These Acts and their respective provisions are as follows:

- Section 26 of Bombay Regulation IV of 1827;

- Section 16 of the Madras Civil Courts Act, 1873 (3 of 1873);

- Section 3 of the Oudh Laws Act, 1876 (18 of 1876);

- Section 5 of the Punjab Laws Act, 1872 (5 of 1872);

- Section 5 of the Central Provinces Laws Act, 1875 (20 of 1875); and

- Section 4 of the Ajmer Laws Regulation, 1877 (Regulation. 3 of 1877).

Is the Muslim Personal Law Act unchangeable

There has always been controversy surrounding the Shariat Act. It has been evident in various instances where the issue relating to the protection of women’s rights as a fundamental right conflicted with religious rights and customs. In the landmark case of Shah Bano Begum, a sixty two year old woman filed a suit claiming alimony from her former husband. The Apex Court upheld her right to claim alimony, but this judgement was opposed by the whole Muslim community, as they considered the same to be against the Quran. The Shariat Law has remained static, but the Supreme Court has continuously tried to uphold the rights of the citizens, as has happened in this case. The case of Shayara Bano, wherein the age-old practice of Talaq-e-bidat was made unconstitutional, is also a great example of the same. The Shariat Law states that the state must not interfere in the personal matters of Muslims, for which the Shariat Law has already been enacted. It has further been contended by a few that since personal laws do not fall under the definition of ‘laws’ under Article 13 of the Constitution, the validity of any personal law can never be challenged as going against fundamental rights.

Instead of an omnibus approach, the government can bring such separate subjects as marriage, divorce, adoption, succession, and maintenance into a Uniform Civil Code for all citizens. There should be a codification of all personal laws with the aim of bringing all prejudices to the forefront and testing them on the basis of fundamental rights as provided under the Constitution.

Tussle between Muslim Personal Law and the Indian Succession Act, 1925

Though the present Chief Justice of India, DY Chandrachud, had already stated that Muslims living in India are to be covered by the Shariat law whether they believe in their religion or not, it has again been contended before the Supreme Court recently that Muslims who do not want to be governed by the Shariat law should be allowed to be covered by the Indian Succession Act, 1925, in both the matters of intestate and testamentary succession. The petitioner highlighted the Sabrimala judgement of 2018, wherein the court focused on the right to freedom of religion under Article 25 of the Constitution. As per the petitioner, freedom includes the right to not believe in religion. Under Muslim law, the rules of succession are different. A wife takes 1/8th of the husband’s property if they have lineal descendants and only 1/4th if there are no lineal descendants. Also, a Muslim’s property can only pass to a Muslim, which further affects his wife and children who are not Muslims.

At present, Muslims who do not want to be governed by Shariat law and formally declare to opt out of the Act would be left without any law governing their inheritance and succession matters because Section 58 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, specifically excludes Muslims. There is one exception for the same: in the case of testamentary succession, when the immovable property is located in West Bengal, Chennai, or Mumbai, Muslims are covered under the Act of 1925.

Similarly, in the case of Sabina Yusuf Lakadawala vs. Union of India (2023), a writ petition was filed under Article 32 of the Constitution by a Muslim woman demanding equal rights in succession for everyone, irrespective of religion. It was claimed that all citizens should have equal rights to inheritance, irrespective of their religion. This plea challenged the validity of the Shariat Law of 1937 in the matters of marriage, divorce, and succession as being violative of Articles 14, 19, and 21 of the Constitution. She contended that the Shariat Law discriminates between the sons and the daughters and widows and is therefore unconstitutional. However, the Supreme Court bench consisting of Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul and Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia dismissed the said petition and stated that this falls within the domain of the legislature.

There is definitely a need for a secular law in these matters as well, and even the Court has sought responses from the governments, year after year, to assist the courts in these matters.

Landmark judgement of Sameena Begum vs. Union of India (2018)

The judgement given in this case was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of India regarding the practice of instant triple talaq (talaq-e-bidat), Nikah Halala, and polygamy in the Muslim community and the constitutionality of Section 2 of the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937. A demand for the Uniform Civil Code was also made by the petitioners in this case.

The case was heard by a five-judge bench comprising Justice Kurian Joseph, Justice Rohinton F. Nariman, Justice Uday U. Lalit, Justice S. Abdul Nazeer, and then Chief Justice of India, Jagdish Singh Khehar. The petitioners, including Sameena Begum, argued that the practice of instant triple talaq violated their fundamental rights under Articles 14, 15, and 21 of the Indian Constitution. They stated that this practice was arbitrary, gender-discriminatory, and not an essential part of Islamic faith.

The bench delivered a split 3:2 verdict. The majority opinion, authored by Justice Kurian Joseph, Justice Rohinton F. Nariman, and Justice Uday U. Lalit, held that instant triple talaq was unconstitutional. Justice Kurian Joseph, in his opinion, stated that the practice was not integral to Islamic faith and violated the Shariat law. Justice Rohinton F. Nariman, supported by Justice Uday U. Lalit, reasoned that the practice was arbitrary and violated Article 14, as it did not allow for any recourse or reconciliation and left women without any protection. The dissenting opinion, given by Chief Justice Khehar and Justice S. Abdul Nazeer, opined that while instant triple talaq was indeed undesirable, it was a part of personal law and thus beyond the scope of judicial intervention. They suggested putting the practice on hold for six months to allow the legislature to enact a law addressing the issue.

The majority judgement declared the instant triple talaq as void, illegal, and unconstitutional. It marked a significant step towards gender justice and equality for Muslim women in India. After the judgement, the Indian Parliament enacted the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act, 2019, which criminalised the practice and prescribed punishments for those who violated the law. This Act further reinforced the Supreme Court’s stance, ensuring protection for Muslim women from arbitrary divorce.

Uniform Civil Code and Shariat Law

The Uniform Civil Code, or UCC, is a part of Directive Principles of State Policy under Part IV of the Indian Constitution as Article 44 and has been a point of dispute over the years. It calls for the formulation of one law for India that would be applicable to all the religious communities, covering areas like marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, and maintenance, and thereby eliminating the differences that we have now with different personal laws. The UCC has been made applicable to the State of Uttarakhand now and has also been a part of the election manifesto of the Bharatiya Janata Party during 2019 and even this year’s Lok Sabha elections.

Since Shariat Law governs the personal matters of the Muslim community, one of the impacts of the UCC on Shariat Law would be the standardisation of laws irrespective of religious beliefs. Shariat Law also provides for practices that are not permitted under other personal laws, like different forms of talaq and polygamy, and the UCC would likely abolish these practices in favour of a more uniform set of rules that apply to all citizens equally, thereby enhancing gender equality and also promoting women’s rights within the Muslim community. Thus, the implementation of UCC would definitely require careful consideration and a balance between the objectives of gender justice and religious freedom.

Conclusion

The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937, has given a framework for the whole Muslim community by combining religious and customary practices with legal principles. This Act definitely stands as a significant piece of legislation in India for ensuring a Muslim personal law to be applied uniformly to all Muslims living in India in matters of personal affairs. The codification upholds the religious principles that were central to Muslims. The Act also faced various criticisms over these years. One of the most significant is the gender bias that is inherent in the traditional interpretations of Shariat Law, particularly in matters of divorce and inheritance, where women are subjected to receiving less as compared to men. This has sparked numerous debates about reforming and harmonising religious laws with contemporary notions of gender equality and human rights. The three major implications are:

- The Act failed to achieve its purpose of ensuring equal rights for both males and females, which were restricted by the application of customary laws.

- When disputes arise concerning these three subjects of agricultural land, charitable endowments, and charities, courts will not be able to apply Muslim law under the authority provided by the Shariat Act, 1937.

- Because of the absence of provincial laws on these three subjects, state legislatures have the authority to formulate laws on these matters. For example, in the State of Tamil Nadu, Muslims are regulated by Muslim personal law in the subject-matter of agricultural land because there has been an amendment to Section 2 of the Act of 1937 in Tamil Nadu to include these subject matters which are not governed by the Act in general.

Taking note of these three existing loopholes, it can be said that although the legislation seems to walk along with social changes, it walks two steps backwards because of the associated hindrances. The application of Shariat Law should evolve with the modern values of equality and justice, and this continuous evolution will help in sustaining both religious sanctity and equitable treatment of all individuals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Who can make rules under the Shariat Act?

As per Section 4 of the Act, the State Government has the power to state specific rules under this Act.

Which case declared the triple talaq (which was part of Muslim personal law) as unconstitutional?

The case of Shayara Bano vs. Union of India (2017) declared the triple talaq, i.e., talaq-e-bidat as unconstitutional.

Which case solved the conflict between Section 125 of the CrPC and the Muslim Personal Law regarding maintenance?

The judgement given in the case of Mohd. Ahmed Khan vs. Shah Bano Begum (1985) solved the conflict regarding maintenance and stated that Section 125 of the CrPC applies even to Muslim women, ensuring maintenance beyond the iddat period.

To whom and to what extent is this Act applicable?

This Act is applicable to all the Muslim people in India, and it extends to the whole of India.

What is the source of the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act?

The Muslim Personal Law, or Shariat Law, is taken from the writings of the Quran, Hadith (traditions of the Prophet Muhammad), Ijma (consensus of Islamic Scholars), and Qiyas (analogical reasoning).

What is the subject matter of the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act?

This Act governs the issues related to family relations among Muslims, including marriage, divorce, inheritance, succession, dissolution of marriage, maintenance, etc.

References

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/islamic-law-personal-law

- http://www.delhihighcourt.nic.in/library/articles/faimily%20court/family%20law%20and%20judicial%20protection.pdf.

- https://theprint.in/opinion/muslim-personal-law-is-an-embarrassment-adapt-it-to-modern-life-marriage-divorce-adoption/1494440/

- https://scroll.in/article/849068/a-short-history-of-muslim-personal-law-in-india

- https://lawbeat.in/index.php/top-stories/amp/supreme-court-declines-consider-plea-against-validity-shariat-act-1937

- https://legal.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/litigation/sc-dismisses-plea-raising-issue-of-succession-says-matter-falls-under-legislative-domain/105365643

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications