This article has been written by Yashwanth Kumar pursuing Diploma in International Contract Negotiation, Drafting and Enforcement and edited by Shashwat Kaushik.

This article has been published by Sneha Mahawar.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Unfortunately, the state of Andhra Pradesh in India has witnessed distressing incidents characterised by caste-based violence and horrifying acts committed against the Dalit community. The caste system has been a standing tradition deeply embedded in society for centuries. The Varna system, mentioned in the Hindu scriptures known as the Vedas, particularly highlights this hierarchical structure.

Throughout history, the Varna system gradually grew more inflexible. Structured, with one’s social position being influenced by their birth and occupation. According to the Vedas, the Varna system initially emerged as a means of organising labour division. The Shudras, positioned at the rungs of this system, were predominantly tasked with serving the three varnas; Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), and Vaishyas (merchants).

Within the Varna system, it was believed that individuals were born into their varnas based on their karma (actions) in their lives. Shudras were considered to have been born into their status as a result of their previous actions in their previous lifetime. This belief linked an individual’s status to their birth and limited social mobility. The caste system in India has been a subject of debate and reform over time. The Indian Constitution prohibits caste-based discrimination under Article 15 and promotes equality under Article 14, along with justice. Since independence, the government has been committed to uplifting marginalised communities and ensuring their development.

In this article, we will delve into the specifics of two incidents that occurred in Andhra Pradesh. We will also explore the factors that led to these massacres and analyse their long term impact on the communities.

Introduction to the Karamchedu and Tsunduru Massacres

The Karamchedu and Tsunduru Massacres are hunting reminders of India’s deeply rooted caste-based violence. In 1985 and 1991, these events took place in Andhra Pradesh, leaving an impact on the country. To fully grasp the importance of these incidents, it is essential to delve into the context of violence based on caste in India.

Historical background of caste-based violence in India

Caste-based violence has been prevailing in the country for centuries. The caste system is a social hierarchy that places individuals into hierarchical groups based on birth. The caste system has deeply influenced cultural practices leading to societal divisions and conflicts. Throughout history, individuals of all castes have endured atrocities, marginalization and violence at the hands of dominant castes. The historical background of caste-based violence can be traced through various periods:

Ancient period

- The caste system finds its origins in ancient Hindu scriptures, particularly the Manusmriti, which laid down rules for social stratification and prescribed different duties for different varnas.

- The rigidity of the caste system and the concept of untouchability led to social exclusion and discrimination against certain groups, particularly the Dalits.

Mediaeval period

- The caste system became more entrenched during the mediaeval period, with various rulers and kingdoms incorporating it into their social structures.

- The emergence of the Bhakti movement in the mediaeval period challenged some aspects of caste hierarchy by emphasising devotion to a single god and the equality of all before the divine. However, the impact on societal practices varied.

Colonial period

- The British colonial administration, which ruled India from the 18th to mid-20th centuries, institutionalised caste distinctions and created policies that further marginalised certain groups.

- The census operations conducted by the British categorised and enumerated people based on caste, contributing to the solidification of social divisions.

Post-independence period

- Despite efforts to eliminate caste-based discrimination in the Indian Constitution with affirmative action policies and legal protections for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, social and economic disparities persisted.

- Violence against Dalits and other marginalised groups continued, often manifesting in the form of atrocities, discrimination, and social ostracism.

Contemporary period

- Caste-based violence remains a significant issue in contemporary India, with incidents reported across the country.

- Economic, educational, and political empowerment programmes have been implemented to uplift marginalised communities, but challenges persist due to deeply ingrained social attitudes and economic disparities.

Several high-profile incidents of caste-based violence, such as the atrocities against Dalits and inter-caste marriages, highlight the ongoing struggles in dismantling caste-based discrimination and violence in India. Various social and political movements continue to advocate for the eradication of these deep-rooted inequalities.

The Karamchedu Massacre

The Karamchedu Massacre took place in 1985 in the village of Karamchedru, located in Andhra Pradesh. This tragic event shook the nation. Shed light on the harsh reality of violence based on caste divisions in our country. On July 17th, 1985, a group of individuals belonging to the Kamma caste launched a divisional attack on the village of Kramchedu.

The genesis of this massacre is that the Dalits used to drink water from a water tank in the village and a Kamma youth did an inhuman thing on July 16, 1985. He washed his buffalo near the water tank and let the soiled water into the tank. This incident was seen by a Dalit youth, and he confronted him about this heinous act. Then, the former bet the latter with his cattle whip and at the same time, there was a girl who came to fetch water, and she was also beaten by him.

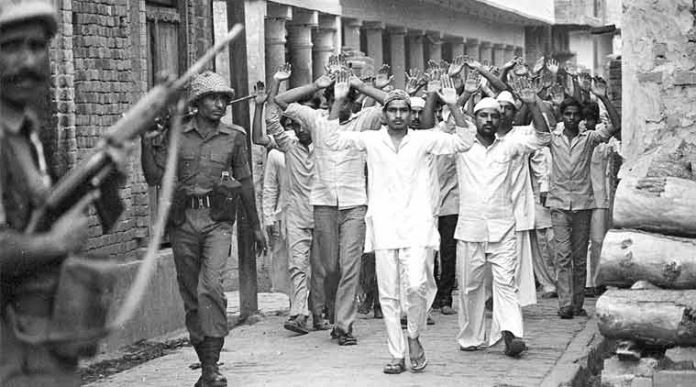

This incident greatly affected the pride of the Kamma people, and they wanted to teach a lesson to the Dalits. Then the Kamma people planned to attack the Dalits, so the following morning the Kamma people got equipped with axes, spears, and clubs and launched a surprise attack on Dalit people; they didn’t even spare pregnant women and mothers with children. They destroyed everything and even tortured some Dalits. The Dalits tried to outrun the village and fled to the neighbouring Chirala town, which was about 8 kilometres away. The police in Chirala acted inhumanely and arrested the Dalits instead of helping them. A refugee camp was organised for Dalits in a church in Chirala town. The camp consisted of about 500 Dalits.

The police, who are supposed to protect citizens and maintain law and order, did not arrive until the massacre was over. And instead of arresting them, the police harassed and threatened the Dalits. The Kamma people tried to suppress the massacre with their political, social and economic power. The media, which is considered a fourth pillar of democracy, has ignored this heinous incident. The outcome of this brutal attack was that six Dalits were dead, over 20 others were injured and three cases of rape were reported.

As a result of this incident, Dalit Mahasabha was formed in Andhra Pradesh on September 1, 1985, by intellectuals like Bojja Tarakam and Katti Padma Rao. The Dalit Mahasabha strived very hard to ensure justice for the victims of this massacre.

The case was filed and in 1991, the trial court acquitted all the accused due to an alleged lack of evidence. The trial court’s judgement was challenged in the High Court of Andhra Pradesh. In 1994, the High Court of Andhra Pradesh reversed the trial court’s judgement and convicted 30 people. However, it is worth noting that nine individuals were given life sentences as a result, while others received prison terms. A plea was made to the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India to increase the punishment for all those convicted. In 2007, after consideration, the Hon’ble Supreme Court upheld the judgement made by the A.P. High Court; however, they did reduce one person’s sentence to life imprisonment.

The incident of this mass killing was a reminder for the people in India, prompting a renewed emphasis on tackling the issue of discrimination. Despite some progress being made since then, instances of violence based on caste divisions continue to persist in our society. The struggle for justice following the Karamchedu Massacre reminds us of how we need legal protections and comprehensive measures to combat these forms of violence and discrimination.

The struggle for justice in the aftermath of the Karamchedu Massacre serves as a reminder of the need for stronger legal safeguards and comprehensive measures to address these types of caste-based violence and discrimination.

Tsunduru Massacre

In the year 1991, there was an incident of caste related violence that took place in the village of Tsunduru, Andhra Pradesh. This event, known as the Tsunduru Massacre, bears similarities to the Karamchedu Massacre. It involved a clash between the Reddy caste and Dalit community triggered by issues surrounding land ownership and power imbalances.

On August 6, 1991, Tsunduru village in Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh became witness to a massacre that continues to be a stain on India’s history of caste relations. This tragic incident took place as a result of an occurrence in which a Dalit boy accidentally touched a Reddy boy’s foot while they were both sitting in a cinema hall. In response, the Reddy youth targeted the Dalit boy. Forcefully made him consume alcohol. Afterwards, they brought him to the police station under allegations of behaviour towards women while he was intoxicated. Another incident occurred where a Dalit boy was accused of brushing against two Reddy girls outside the cinema hall. These two incidents led to a boycott against the Dalits that lasted over a month. As a result, they had to travel to Tenali to purchase necessities and groceries and due to the boycott, many had to seek work in Ongole.

Originally, the Dalits were economically underprivileged. They worked as labourers on fields owned by people belonging to the Reddy caste. However, recognising the importance of education in breaking free from their status, Dalit families encouraged their children’s education. As a result of this support from their families, the literacy rate among the Dalits is higher compared to higher caste communities like Reddy’s. A significant number of Dalits have obtained bachelor’s degrees from Ambedkar College in Tenali.

As the Dalits became more educated, they began to challenge the caste system and boundaries within the village. This act of defiance was seen as a violation of honour by the upper caste individuals, which further escalated tensions and led to this massacre.

The Reddy community has both economic and political support and the cooperation of the police, who endorsed the massacre. They neither actively participated in nor overlooked the attacks on Dalits. Without police backing and cooperation, organising such a massacre would have been exceedingly difficult for the Reddy community. On August 6th, 1991, the police arrived at Dalit’s houses unexpectedly, prompting Dalit men to flee to nearby fields where members of the upper caste awaited them with deadly weapons like axes, iron rods, spears, sickles, ploughs, etc. As soon as the upper caste individuals spotted the approaching Dalits, they ruthlessly launched an assault using their weapons. Some bodies were dismembered and their parts stuffed into gunny bags. Other members sustained multiple wounds and severe injuries, while all the stuffed gunny bags were discarded into the nearby Tungabhadra canal. Due to this massacre, a total of 8 Dalits were killed by the Reddy’s. During the following days of the massacre, the Dalits actively searched for the missing men who had been targeted in the attack. Without any assistance from the police, they successfully recovered all the bodies that had been concealed. Finally, it became undeniable to law enforcement that a significant incident had indeed occurred at Tsunduru. Unfortunately, when the corpses were discovered, they were already severely swollen and decomposed. Understandably distressed by these grim findings, most Dalit families chose to flee Tsunduru and find safety in Tenali. Eventually, they brought the retrieved bodies to the Tenali government hospital. The doctor responsible for conducting post-mortems on these bodies couldn’t digest the brutality of the murders and later took his own life by hanging.

The pursuit of justice for the Tsunduru victims has been a long and difficult legal battle. To ensure fair proceedings, a special court was established in Tsunduru, which was rare and unprecedented. In 2007, this court sentenced 21 accused to life imprisonment and 35 others to one year imprisonment. However, in 2014, the Andhra Pradesh High Court overturned the verdict due to a purported lack of evidence and inconsistencies in the prosecution’s case. Currently, the matter is with the Supreme Court, where both the victims’ families and activists remain hopeful for a favourable outcome.

The Tsunduru Massacre shed light on the rooted biases and discrimination prevalent in society. It emphasised the pressing need for measures to combat caste-based prejudice and violence. Additionally, this incident served as a catalyst for political movements striving to dismantle the caste system and seek justice for victims affected by heinous acts.

Socio-political implications of Karamchedu and Tsunduru Massacres

The Karamchedu and Tsunduru Massacres had political consequences both at a local and national level. These tragic events shattered the illusions of an equal society, revealing the reality of caste driven violence. The massacres sparked discussions on issues like caste-based discrimination, the importance of justice and the necessity of affirmative measures to empower marginalised communities.

At a national level, the Karamchedu and Tsunduru Massacres had significant implications for legislative reforms and policies concerning caste-based discrimination. These tragic incidents compelled both the government and society to confront the deeply rooted prejudices and inequalities that perpetuate caste violence. As catalysts for change, these massacres spurred efforts towards improved representation and opportunities for historically marginalised communities.

The aftermath

The consequences of the Karamchedu and Tsunduru Massacres had an impact on matters of justice, rehabilitation and reconciliation. These incidents deeply wounded the Dalit community and the response to these massacres varied in its approach to seeking justice and healing.

The Supreme Court delivered the final verdict 23 years after the Karamchedu Massacre and 17 years after the Tsunduru Massacre. Both cases experienced significant delays in their legal proceedings, shedding light on the challenges faced by victims and survivors seeking justice for caste-based violence. Despite these hurdles, the convictions of certain perpetrators offered some solace and closure to the affected individuals and their families. Both massacres resulted in Dalit communities being uprooted, forcing families to leave their homes and find refuge elsewhere. The survivors encountered challenges in rebuilding their lives and livelihoods. The state government, along with civil society organisations, played a role in providing support for rehabilitation, such as shelter, healthcare services and economic assistance. However, rehabilitation proved to be a process as survivors continued to grapple with the social impacts of these violent events.

Finding comfort after such traumatic experiences can be incredibly challenging and it requires effort over the long term. The Dalit community, along with activists and organisations, actively strives to promote dialogue and understanding among castes. Their efforts towards reconciliation aim to bridge gaps, address historical grievances and foster social harmony. Moreover, survivors receive assistance through healing programmes that include counselling and support for trauma recovery, helping them overcome the distressing massacre they have endured.

The Karamchedu and Tsunduru Massacres received attention both within India and internationally. These tragic incidents highlighted the violence based on caste in India, exposing the seated inequalities and discrimination faced by the Dalit community. As a result, various international human rights organisations united to advocate for the protection and well being of this marginalised group.

The aftermath of the Karamchedu and Tsunduru Massacres showcases the difficulties faced by individuals who have suffered from violence based on their caste. These incidents had a lasting effect on Dalits and have played a significant role in shaping conversations about caste discrimination, underscoring the pressing need for reform in India. For justice, ongoing rehabilitation efforts and healing programmes necessitate sustained commitment from all stakeholders to address the root causes of caste-based violence while fostering harmony and equality.

Legislative measures to prevent atrocities

The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989

In 1989, the government enacted the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, also known as the PoA Act, to tackle the discrimination faced by individuals belonging to SC and ST communities. This Act prevents incidents of violence and discrimination based on caste. In 2015, the Act underwent amendments that broadened its scope to include forms of atrocity committed against Dalits and Adivasi women. These new provisions cover offences such as assault, sexual harassment and Devadai dedication.

Special cells and courts to address atrocities against SCs/STs

In Andhra Pradesh, specific measures have been implemented to ensure the implementation of the Prevention of Atrocities Act. A specialised unit known as the Special Cell has been established within the Police Department, operating under the CID office and headed by an IGP/DIG. This dedicated cell focuses on expediting investigations, prosecutions and overall management of cases related to untouchability offences and atrocities against SCs/STs. The expenses for this PCR cell in CID are fully covered by the Social Welfare Department.

Furthermore, Special Sessions Courts have been set up in Andhra Pradesh with the purpose of handling cases pertaining to atrocities against SCs/STS, under the Prevention of Atrocities Act enacted in 1989.

These specialised courts, led by designated judges and supported by public prosecutors who were appointed under this SC ST (PoA) Act, have the goal of establishing a platform to ensure that cases related to caste-based crimes are fairly resolved.

Efforts to protect marginalised communities and promote equality

After the enactment of the SC and ST Acts, many Special Cells and Courts were established to safeguard the oppressed and marginalised communities and the main aim of this Act is to promote equality as guaranteed under Article 14 of the Indian Constitution.

The government should provide quality education, employment opportunities, and financial support to marginalised communities and it should also conduct awareness campaigns on this social evil. The government alone cannot do all of this; we, as the citizens of this country, must take part in these programs and the NGOs should also make certain awareness programmes regarding this social evil.

The government and the NGOs, along with the citizens, can make this social evil of caste discrimination disappear from society.

The impact of media and public awareness in tackling violence based on caste

There are three pillars in democracy, legislative is the first, executive is the second, judicial is the third and media is often considered the fourth pillar of democracy. The media has ignored these incidents in the first instance. But many journalists and activists worked hard to reveal the bitter truths of these two massacres. Due to the hard work of these journalists and activists, the massacres received huge public support and agitations were started for justice for the victims.

Due to the unwavering work of these journalists, the victims of these massacres received huge public support throughout the country and several movements were started to make sure the victims received justice.

Conclusion

Both the Karamchedu and Tsunduru Massacres are live examples of the caste based discrimination, even in this modern era. Thus, these incidents proved that social evil, i.e., caste discrimination, is still prevailing in our country and is embedded in the nature of some people. Due to these massacres, the SC, ST (PoA) Act was enacted to safeguard the oppressed caste people. Due to the stringent nature of this Act, it has shown some effect in defeating caste discrimination, and this Act is a clear example that caste discrimination is both an offence and a social evil, and the offenders will not go unpunished. We, as educated people, should prevent this social evil and eradicate this discrimination in our country. India is a diverse country and we believe in “Unity in Diversity”, so as the citizens of this country we must unite and eradicate this social evil from our country and must treat the oppressed people with dignity and respect. We, as the citizens of this country, must create awareness about this evil practice and should make sure that our future generations do not suffer because of this social evil.

References

- https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/35-years-after-karamchedu-massacre-andhra-dalit-activists-speak-what-has-changed-128944

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tsundur_massacre#Massacre

- https://feminisminindia.com/2019/04/30/tsunduru-massacre-dalits/

- https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/andhra-pradesh/tsunduru-dalit-massacre-a-bloodsoaked-chapter-in-modern-history/article4996786.ece

- Remembering Karamchedu: The brutal massacre which spurred Andhra’s Dalit movement – Kractivism (kractivist.org)

- The Karamchedu Killings and the Struggle to Uncover Untouchability (Chapter 3) – Dynamics of Caste and Law (cambridge.org)

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals, and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications