In this blog post, Gayatrisagar Chopra, a student pursuing her BLS, LLB (5h year) from Pravin Gandhi College of Law, Mumbai and a Diploma in Entrepreneurship Administration and Business Laws from NUJS, Kolkata, critically analyses the investment structure used by Vodafone to minimize the burden of paying capital gains tax in the recent Vodafone v. Union of India case.

The Case

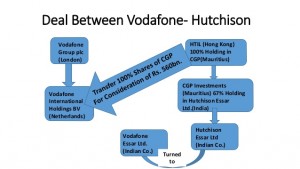

In the light of the case of Vodafone v. Union of India[1], the petitioner Vodafone (based in Netherlands) acquired Cayman Islands-based Company CGP Holdings Limited from Hutchinson Telecommunications International Limited. The deal was concluded at 11.1 billion dollars, as CGP Holdings controlled 52 % of Hutichison-Essar Limited (based in India) and had the option to buy 15 % more hence as a consequence of this acquisition Vodafone had effective control of 67% over Hutchison-Essar. The Indian Income Tax Authorities claimed that Vodafone was to pay capital gains tax on capital gains accrued due to the consequent control of Hutichison-Essar Limited. The amount of tax payable was estimated at 2.5 billion dollars.

Bombay High Court

The Tax Authorities filed a case against Vodafone in the Bombay High Court. The court held that a prima facie case was made out by the Tax Authorities of transfer of Capital Assets, and therefore accrual of Capital Gains and hence was liable to pay the Capital Gains tax. Hutchison- Essar being a company situated in India was seen by the Income Tax Authorities as the Target Company, and they contended that the purpose of the acquisition of CGP was to acquire effective control in Hutchison- Essar. Vodafone contended that the Tax Authorities had no territorial jurisdiction over the transaction as the acquiring company as well as the company acquired were not based in India.

Supreme Court

Vodafone in its turn filed a Special Leave Petition before the Supreme Court. The Apex Court held that the Bombay High Court had erred in its decision and should have employed a “look at” approach instead of a “look through” approach. They emphasized on the theory of Corporate personality wherein the identity of the shareholder is distinct from that of the company. The Court said that the authorities must look at the transaction at its face value rather than the hidden intent behind it. The acquisition of CGP Holdings was not solely to gain control over Hutchison-Essar, but the gain in control was a corollary of the acquisition, which was not the purpose of the acquisition.

Capital Gains

Capital Gains Tax[2] under the Income Tax Act is tax payable on the “transfer of a capital asset situated in India.”[3] Capital Assets according to the Income Tax Act, 1961 is “property of any kind held by an assessee, whether or not connected with his business or profession.”[4]

According to Section 9 (1)(i) of the Act, which forms the heart of the controversy, income accruing indirectly or directly out of transfer of Capital Assets situated in India is deemed to accrue in India out of the hand of a Non-Resident. The Supreme Court expressed its view in this regard stating that the transfer of shares of CGP did not result in a transfer of Capital Assets.

Structuring

According to the views expressed by the Supreme Court, there were two possible structures available for such a transaction to include a tax-free entity, to either include CGP or route the deal through Mauritius. Therefore, by structuring the deal through CGP, they have transitioned the business in a smooth manner. Thus, the sole purpose of the CGP acquisition was not to control Hutchison-Essar. This smart structuring through layers of Investment subsidiaries in tax-free jurisdictions saved Vodafone the payment of an exorbitant tax. Also, fanning the control through multiple companies and not a nodal structure helped Vodafone.

Conclusion

Thus, smart investment structures such as the one created by Vodafone help in avoiding large tax amounts in jurisdictions such as India where the taxation rates are high and taxation laws are extremely stringent despite measures like Double Taxation Avoidance and Advance Pricing.

[divider]

Footnotes:

[1][S.L.P. (C) No. 26529 of 2010, dated 20 January 2012]

[2] Section 45 Income Tax Act, 1961

[3] Section 9 Income Tax Act, 1961

[4] Section 2 (14) Income Tax Act, 1961

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications