CASTE BASED RESERVATION

India is the world’s largest democracy, yet in spite of this, it has been subjected to a hoard of controversies owing to the caste system. The caste system which is prevalent to date has been a fundamental part of Indian culture for time immemorial. This system led to the subjugation of the “lower castes” by the “higher castes.” Thus to improve the situation of the lower castes, the Government of India introduced caste based reservation in governmental jobs and educational institutions. But the question remains whether this has been beneficial or if it has led to further enhancement of the differences? Or whether the income/economic-based reservation scheme is a better option?

History of Caste Based Reservation in India

The first written text which talks about the caste based system or “dharma of the four social classes” in its entirety is the Manusmriti. It says that every individual’s job was fixed by their birth.

In modern India, some of the notable instances are from when in 1933, the then Prime Minister of Britain, Ramsay MacDonald established the Communal Award. A separate representation awarded to Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians and Europeans. This award was strongly opposed by Mahatma Gandhi who fasted unto death to express his displeasure. However, it received immense support from the likes of B. R. Ambedkar. After several negotiations, Gandhi called off his fast and the Poona Pact was a result of these negotiations.

However, this wasn’t the first instance where the demands for “special status” were made by the minorities. Incidents date back to as early as 1891 when in the Princely State of Travancore there was a demand for caste based reservation in government jobs. The first official instance was in 1902 in Kolhapur were 50% reservation was provided for in services for backwards classes/communities (BCs).

Post-independence the most significant step was taken in 1979 when the Mandal Commission was formed. It was headed by Indian parliamentarian Bindheshwari Prasad Mandal to consider the question of seat reservations and quotas for people to redress caste discrimination, and used eleven social, economic, and educational indicators to determine “backwardness.” In 1980, the commission’s report affirmed the affirmative action practice under Indian law whereby members of lower castes (known as Other Backward Classes and Scheduled Castes and Tribes) were given exclusive access to a certain portion of government jobs and slots in public universities, and recommended changes to these quotas, increasing them by 27% to 49.5%.

But today are these reservations actually being implemented as was envisioned by our policy makers? The answer is prima facie ‘NO’ because the benefits are being stolen away by the “creamy layer.”

The Reservations Against Reservation

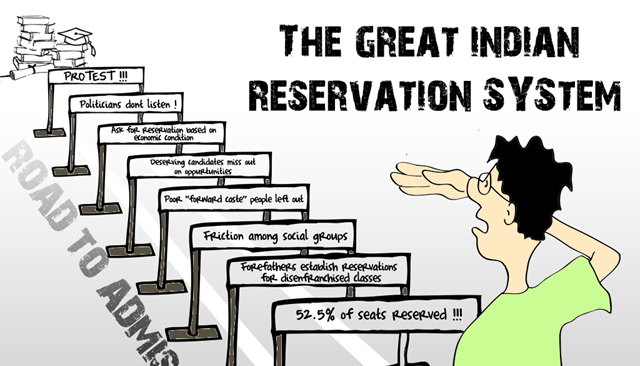

In accordance with the 93rd Constitutional Amendment, the government is allowed to make special provisions for “advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens”, including their admission in aided or unaided private educational institutions. And it was proposed that this reservation policy should be gradually implemented in private institutions and companies. This move faced severe opposition from non-reserved category students, as it reduced seats for the General (non-reserved) category from the existing 77.5% to less than 50.5% (since members of OBCs are also allowed to contest in the General category).

Article 15(4) of our constitution empowers the government to make special provisions for advancement of backward classes. Similarly, Article 16 provides for equality of opportunity in matters of employment or appointment to any post under the State.

“Clause 2 of Article 16 lays down that no citizen on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, residence or any of them be discriminated in respect of any employment or office under the State.”

However, clause 4 of the same article provides for an exception by conferring a certain kind of power on the government:

“it empowers the state to make special provision for the reservation of appointments of posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which in the opinion of the state are not adequately represented in the services.”

In a case Balaji v/s State of Mysore[1] it was held that ‘caste of a person cannot be the sole criteria for ascertaining whether a particular caste is backward or not. Determinants such as poverty, occupation, place of habitation may all be relevant factors to be taken into consideration. The court further held that it does not mean that if once a caste is considered to be backward it will continue to be backward for all other times. The government should review the test and if a class reaches the state of progress where the reservation is not necessary it should delete that class from the list of backward classes.’

Thus, the underlying premise of the philosophy of reservation that all members of the “backward classes” are disadvantaged, while all members of “forward castes” are deemed to be good enough to get admission under their own steam is in my opinion, not a valid assumption; neither is it fair. Economic considerations cannot be ignored when arriving at who needs extra care in and by our society.

What is ironical is that even though our constitution is reservation friendly, nowhere in a bare reading of the Constitution is the term ‘backward classes’ explicitly defined. What determines the backwardness or constitutes backwardness are still unanswered and only with the help of certain judicial pronouncements have they been given some meaning.

So the question arises, how can there be reservation for something that is undefined?

In all honesty, It must be appreciated that affirmative actions are taken to ensure that a level playing field is created for the under-privileged sections of our country. The issue is how for over the past 30 years nearly every government – no matter how “secular” they claim to be – has been trying to turn this socio-economic issue into an issue of dirty vote bank politics, communalism and a matter of pride.

The result: In individual states such as Tamil Nadu or within the north-east, where backward populations predominate, over 80% of government jobs are set aside in quotas, despite a Supreme Court ruling that 50% ought to be the maximum.[2]

Furthermore, the reservation policy is applicable only to higher institutions. Thus it does nothing to promote education at the primary level. Millions of children will still be denied access to even basic schooling- and it is this lack of primary schooling that often denies access to future education and employment opportunities.

Kapil Sibal erred even more than his successor in the present government, when as Human Resources Development minister he ordained 25% reservation (free seats) in private schools. Teachers of such schools are finding it impossible to bring such children on par with other bright children despite their best efforts.

Also, a sense of complacency has been instilled in students by the abolition of final exams as a criterion for being promoted up to class 10, after which they are left to the mercy of uninterested and grossly underpaid evaluators.

This is not to suggest that children from the poorer strata of society or from backward classes should be condemned to mediocrity or illiteracy. Instead, the answer lies in upgrading the education provided in government institutions. This would call for painstaking efforts in the appointment of teachers and a better pay scale which is at par with those of their private counterparts. Also analysing the American model of education would not be a bad idea, where 87% of children from kindergarten to grade 12 attend public schools[3]. Sadly in our country, the idea of private schools has somehow acquired elitist connotations.

To quote an example, the decision of IIT Roorkee to expel 73 students with poor performance was an eye-opener to the condition of many kids who make the near impossible entry into the IIT campuses. A report by The Indian Express[4] suggested that 90% of the expelled students were from SCs, STs and OBCs. Another instance that could be stated is of the “alleged suicide” of a Dalit student at IIT Mumbai last year which gives us a glimpse into the suffering of backward caste students in institutions such as IITs. His performance had been poor, he had uncleared papers and was subject to taunts by general category students and shockingly a faculty member too. Reporting this case, DNA said that about 56% of students under reserved category felt discriminated against. Moreover, 60% of them also felt more pressured by academics than the general category students. There is a growing concern, the government might be trying to ensure a level playing a field, but it is failing- and miserably so- to ensure that they benefit from it. There are about 50% seats reserved for them, but if most of them fall through the cracks- as the above instances show- it serves no purpose.

Further, now being included in the list of backward classes/SCs/STs is now being viewed as a “status symbol,” the recent Jat agitation serves as the best example. This demand- by a group considered a “dominant caste” in the Northern part of our country- to be treated as a backward caste, put lives of many in jeopardy and affected livelihoods of people in three states. So the question is for how long can the demand for “privileges” as a “backward” class be maintained at the expense of a majority of the population.

THE OTHER ALTERNATIVE

Caste based reservation policy fails to recognize social backwardness as a fluid and evolving category. Gender, culture, purchasing power and so on could also influence capabilities, and any one of these, or a combination of these, could be the cause of deprivation and social backwardness. With increasing globalization and urbanization, caste loyalties are weakening and hence, new parameters to define social backwardness need to be identified. Reservation should explicitly include economic criteria. A rich person (irrespective of caste) can access and afford education for his/her children and does not need the protection offered by the reservation policy. Because in today’s world the correlation between the economically backward and the lower caste may not be as strong as it was earlier. It is the poor who need such protection- irrespective of their caste. Rather than debate about what constitutes the “creamy layer” and how it is to be defined, everyone should be given an equal opportunity to prove their worth. No section of society should be spoon fed. Instead, they should be provided with adequate resources, and at the end of the day, merit should prevail.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

https://t.me/joinchat/J_

References –

[1] (AIR 1963 SC649)

[2] http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2013/06/affirmative-action

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Education_in_the_United_States

[4] http://www.firstpost.com/india/90-percent-of-iit-roorkee-dropouts-are-backward-caste-a-case-against-affirmative-action-2379964.html

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications

underline

[…] Reformation of the Reservation system in India. Image Credits: iPleaders Blog […]

reservation not good for india it’s sneching india back

Reservation is an ‘unfortunate’ system. I am using the word ‘unfortunate’ to define it because of the existence of the caste system, which is the reason for reservation. Caste is an unfortunate and ugly truth in Indian society.