This article is written by Aditya Singh from Symbiosis Law School, Noida. This article deals with the analysis of the noteworthy Oleum Gas Leak case in which the Supreme Court established itself the protector of Article 21 and of the public rights by adopting the principle of absolute liability. The article also observes the contemporary relevance of the case.

Table of Contents

Introduction

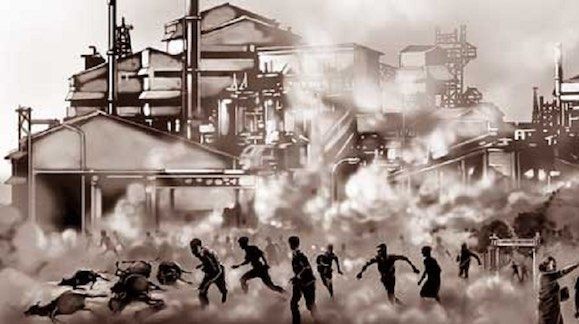

The Oleum Gas Leak incident being similar in nature brought back the horrors of the Bhopal gas disaster, as a large number of people including both working people and the public were affected only after one year of the Bhopal gas tragedy and was closely monitored as an example as to how the courts should deal with companies accountable for environmental disasters. The complicated legal proceedings around the Bhopal Gas Tragedy is sadly an example of what should not be done in this situation.

Oleum gas from Shriram Foods and Fertilizers which was a fertilizer plant leaked causing harm to numerous people. The Ryland v. Fletcher rule was applied in this case. J. Bhagwati stated that the above rule has been 100 years old and is not enough to decide cases such as these, as science has improved a lot in these years, which is why the Supreme Court went a little further and implemented the absolute liability rule.

To know more about the Oleum gas leak case in brief, please refer to the video below:

Background facts

In the centre of a population of 200,000 people in the area of Kirti Nagar, Shriram’s Food and Fertiliser factory, Delhi was situated, which produced products like hard technical oil and glycerin soaps. M.C. Mehta, a social activist lawyer, submitted before the Supreme Court a writ petition seeking an order for closure and relocation of the Shriram Caustic Chlorine and Sulphuric Acid Plant to an area where no real danger to the people’s health and security will exist. Pending disposal of the petition, the Supreme Court allowed the plant to restart its capacity and work. On 4 and 6 December 1985, Oleum gas leaked from one of its units during the pending lawsuit, causing substantial harm to local residents as a result of the plant’s gas leakage.

As stated by the petitioner, a lawyer who practised in the Tis Hazari Courts also died as a result of oleum gas inhalation. As a result of the collapse of the structure on which it was built, the leakage resulted from the bursting of the tank containing oleum gas, and it generated fear among the citizens residing there. The people had hardly recovered from the shock of this tragedy when, within two days, another leakage occurred, though this time a minor one, due to the escape of oleum gas from a pipe’s joints, after which the claims for compensation were filed, for the people who had suffered damage as a result of Oleum Gas escape, by the Delhi Legal Aid & Advice Board and the Delhi Bar Association.

The Delhi administrations immediate response to these two leaks was to issue an order dated 6th December 1985 by the Delhi Magistrate, in accordance to sub-section(1) of Section 133 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, ordering and requiring Shriram to cease the occupation of manufacturing and processing of dangerous and lethal chemicals and gasses, including chlorine, Oleum, Super Chlorine, phosphate, etc. at their facility in Delhi and to remove such chemicals and gasses from the facility within 7 days and to refrain from storing them in the same place again or to appear in the District Magistrate Court on 17 December 1985, to show cause as to why this order should not be enforced.

The Supreme Court held that the case should be referred to a larger bench because the questions raised involve substantial law issues relating to the interpretation of Articles 21 and 32 of the Constitution. In order to assess whether a writ in conjunction with compensation could be awarded, the court had to interpret Article 32. In relation to the private companies Article 21, which establishes the right to protect life and freedom, was also to be interpreted as being essential in the public interest.

Issues

The oleum gas leak case led to various issues to come into the light, which was:

- Whether these harmful industries should be permitted to operate in these areas?

- Whether a regulating mechanism should be established if they are permitted to function in such areas?

- How should the liability and amount of compensation be determined in such cases?

- How does Article 32 of the Constitution extend in these cases?

- Whether the rule of Absolute Liability or Ryland v Fletcher is to be followed?

- Whether ‘Shriram’ could be considered to be a ‘State’ within the ambit of Article 12?

Judgment

Showing extreme concerns for the safety of the people of Delhi from the leakage of hazardous chemicals, J. Bhagwati stated the proposal to eliminate toxic and hazardous factories could not be followed because they still contribute to improving the quality of life. Industries must, therefore, be established even if they are harmful as they are necessary to economic and social development. He was of the view that the risk or danger factor towards the public can only be hoped to be reduced by taking all the measures required to position these industries in an environment where the public is least vulnerable and the safety requirements are maximized in such industries. It was also noted that permanent factory closure would result in the unemployment of 4,000 workers in the caustic soda factory and which would add to the social poverty problem. Consequently, the court ordered that the factory be opened temporarily under 11 conditions and appointed a committee of experts to control the activity of the industry.

The main provisions set up by the government were:

- The Central Pollution Control Board appoints an inspector to check that emissions levels are in compliance with the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 and the Air (prevention and control of pollution) Act, 1981.

- To create a safety committee for employees.

- Industry to publicize about the consequences and the proper treatment of chlorine.

- To train and instruct the employees regarding the safety of the plant through audio-visual services and to install loudspeakers to alert neighbours in case of gas leakage.

- Staff to use protective equipment, such as helmets and belts.

- That the employees of Shriram furnish the undertaking of the Chairman of Delhi Cloth Mills Limited that they will be “personally liable” for paying compensation for any death or injury in the event of gas escape resulting in death or injury to staff or people living in the vicinity.

Through these conditions have been formulated with respect to the report of the (Manmohan Singh Committee and Nilay Choudhary Committee) to ensure that there is continued compliance with safety standards and procedures so that the potential hazard and risk of workers can be reduced to minimal. In addition, companies can not abandon liability by demonstrating that they are either not reckless about or have taken all the required and appropriate measures to deal with the hazardous material. Therefore, in this case, the court applied the principle of absolute liability.

The court noted that, in addition to issuing guidance, new approaches and methods designed to enforce fundamental rights could be developed under Article 32 and the Supreme Court. In the event of a threat to fundamental rights, the power under Article 32 is not limited to only preventive actions, but it also applies to remedial acts where rights are already being violated as observed in the case of Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India. Furthermore, in cases where a fundamental right violation is gross and affects large-scale people or people who are disadvantaged and backward, the court has held that it has the power to offer remedial relief.

The court also went through the Industrial Policy Resolution 1956 and on the basis of the role the state should play in each of them the industries were divided into three groups. The first was the responsibility of the State alone. The second group was those industries that would eventually be State-owned in which the State would then typically take the initiative of setting up new enterprises but it will also be required that the private companies would complement the State’s efforts by supporting and establishing enterprises by themselves or involving the state for its help. The third group would cover all other sectors and would usually be left to the private sector initiative and companies.

If a review of the declarations contained in the Policy Resolutions and the Act is carried out, it is found that the activity of producing chemical products and fertilizers is considered, to be a vitally important part of the public sector, the activities involving the public trade must ultimately be conducted by the State itself, within the interim term with state support and under State control and the private enterprises may also be allowed to support the state effort. Although the question of whether a private corporation fell within the ambit of Article 12 of the Constitution of India was not finally decided by the court, it stressed the need to do so in the future.

The court held that all exceptions to the rule set out in Rylands v. Fletcher are not applicable to hazardous industries. The Court adopted the principle of absolute responsibility. The exception available for this case was the act of a third party or natural calamity but the court interpreted that as the leakage was caused due to human and mechanical errors the possibility of an act of third party and natural calamity is out of scope and hence the principle of absolute liability is applicable here. An industry that engages in hazardous activities that pose a potential danger to the health and safety of those who work and live nearby is obliged to ensure that there is no harm to anybody. This industry must perform its operations with the highest safety requirements, and the industry must be completely responsible to compensate for any harm caused by them, as a part of the social cost for carrying such hazardous activities on its premises.

Reforms brought aftermath

The Gas Leak case in Shriram was a very important case in environmental advocacy, as it dealt with Shri Ram Food and Fertilizers, one of India’s largest and richest manufacturing establishments against the Supreme Court, the representative of the people. The Supreme Court considered strict liability insufficient to protect citizens’ rights in a developed economy such as India thereby substituting it with the ‘absolute liability principle’. It set the Indian Supreme Court to be the protector of the environment and under Article 21, not only of the fundamental right to life but also of a pollution-free and safe life. There were many significant points of this case worth noticing. The court also performed the function of an extra-parliamentary body by insisting that the concept of absolute liability be used and thus set a precedent for future cases to come.

The reforms brought by this case can be seen from the latest case of the Vizag Gas Leak Case where LG Polymers would be held responsible and there is no requirement to show that the leak was caused by negligence. The mere fact that the leak happened from their plant is enough. Till the Oleum Gas Leak case, India also followed the concept of “Strict Liability” under which the company owner/ operator would be held responsible for any non-natural acts on his property irrespective of their negligence or misconduct, but then this concept had to be substituted with Absolute Liability as principles under Strict Liability have defences and limited exceptions inclusive of the defence of the ‘Act of God’. It is also necessary to remember that, in keeping with subsequent rulings of the Supreme Court in this matter, the death toll would not be applicable to the determination of liability. Any damage caused by the gas, from death to disease to hospital cost must be covered.

Conclusion

The decision had to be made in such a manner so as not to hinder the economic development of the country and also to ensure justice for the victims. Only a few months before the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 came into force did this incident become a guiding force for the implementation of such an effective law. The case set a precedent for all the industries to establish more stringent safety measures. The gas leak case of Shriram was also noteworthy because it was the first time that a company had been held exclusively responsible for an incident and had to pay compensation irrespective of its claims in defence. The reasons for the decision have also been found not only on a legal basis but also on a scientific basis, which is why a special judicial function has been undertaken by the Supreme Court. The decision was made also in view of the importance of industrialization and the fact that it may eventually result in accidents. The decision was also determined considering the terms of the need for industrialization and the inevitable possibility and the impact of injuries. In general, it was a rational decision, taking all social, economic, and legal factors into account, which made the Supreme Court a defender of the environment and public rights.

References

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/25742002?seq=1

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/759728?seq=1

- https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1486949/

- https://thewire.in/rights/vizag-gas-leak-ngt-strict-absolute-liability

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications