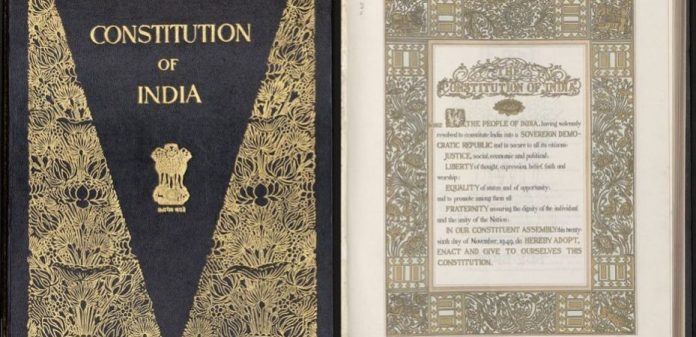

This article is written by M.S.Sri Sai Kamalini, and has been further updated by Sakshi Kuthari. The Indian Constitution is the fundamental law of our country and lays down the various objectives which the State aims to achieve for the people of India. It also lays down the various structures and organs of the government at different levels and outlines the rights and duties of the citizens. This article discusses in detail, the salient features of the Indian Constitution in consonance with the preamble of the Constitution, fundamental rights, directive principles of state policy and fundamental duties.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The Constitution of India is a dynamic and remarkable achievement of our lawmakers. As the Indian Constitution is the supreme law of the land, it is essential for every citizen to adhere to its principles and provisions. Its outlook and expression are perceived and expressed by the interpreters of the Constitution and must be dynamic and one that keeps pace with the changing times. Though the basics and fundamentals of the Constitution remain unalterable, the interpretation of the flexible provisions of the Constitution can be accompanied by dynamism, in cases when a conflict arises, in protection of the weaker or the one who is more needy.

A “state” is defined under Article 1 of the Montevideo Convention as an independent political entity, occupying a defined territory, the members of which are united together for the purpose of resisting external force and preservation of internal order. The definition lays stress on what may be called the ‘police functions’ of the state. India as a state, has all these features.

Making of the Indian Constitution

To know about the salient features of the Indian Constitution, it is also important for us to know about its making. The Constituent Assembly first met and began the work on the Constitution on 26 November, 1946. It held its first meeting on 9 December, 1946. The meeting was attended by 211 members. Dr. Sachdanand Sinha, the oldest member, was elected as the temporary President of the Assembly. Later on, Dr. Rajendra Prasad and H.C. Mukherjee was elected as permanent President and Vice-President of the Assembly respectively. Among all the committees of the Constituent Assembly, the most important was the Drafting Committee, formed under the chairmanship of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar.

The Drafting Committee, after taking into consideration the proposals of the various committees, submitted its report on 21 February, 1948. At that time Draft Constitution contained 315 Articles and 8 Schedules. The people of India were given 8 months to discuss and draft and propose amendments. As many as 7,635 amendments were proposed. In the light of the public comments, criticisms and suggestions, the Drafting Committee prepared a second draft, which was published on October, 1948 and was presented to the Constituent Assembly on 4 November, 1948, for the first reading or consideration.

The first reading comprised general discussion which commenced on 4 November, 1948 and continued till 9 November, 1948. Then began the second reading or consideration of the clauses of the Draft and it continued from 15 November 1948 to 17 October 1949. During this stage, out of 7,635 amendments which were proposed 2,473 were actually discussed in the Assembly. The Assembly then again sat on 14 November, 1949 for the third reading of the Draft and it concluded on 26 November, 1949.

On this date, the Constitution received the signatures of the President of the Constituent Assembly and it was declared passed. It contained 395 Articles spread over 22 Parts and 12 Schedules. Out of a total 299 members of the Assembly, only 284 were actually present on that day and signed the Constitution. A few of the provisions of the Constitution came into force on 26 November, 1949 itself.

The final session of the Constituent Assembly was held on 24 January, 1950, where it unanimously elected Dr. Rajendra Prasad as the first President of the Republic of India under the new Constitution which came into force on 26 January, 1950. The Constituent Assembly took 2 years, 11 months, and 18 days to complete the herculean task of drafting the Indian Constitution. The main reason behind the long time taken by the Constituent Assembly that went on for almost three years was to strike the right balance so that institutions created by the Constitution would not be haphazard or tentative arrangements but would be able to accommodate the aspirations of the people of India for a long time.

In this article, we shall discuss in detail the salient features of the Indian Constitution along with the preamble, fundamental rights, directive principles of state policy and fundamental duties.

Salient features of the Indian Constitution

Lengthiest written Constitution in the world

The Indian Constitution is the lengthiest written Constitutions in the world and it is also very detailed. A written Constitution is the formal source of the Constitutional law in any country. It is regarded as the supreme or fundamental law of the land as it controls and permeates every institution in the country. Every organ in the country must act in accordance with the principles enshrined under its Constitution. The Constitution of India has incorporated various Articles by drawing inspiration from Constitutions across the globe. Originally it consisted of 395 Articles arranged under 22 Parts and 8 Schedules. Currently, after several amendments, the Indian Constitution comprises 448 Articles, 25 Parts and 12 Schedules. It is likely the longest of the existing laws worldwide. Several factors contribute to its length, including the following:

- Firstly, the Indian Constitution deals with the organisation and structure of both the Central and State Governments;

- Secondly, in a federal Constitution, the Central-State relationship is a matter of crucial importance. It has detailed norms on this matter from Articles 245-255 of the Indian Constitution while other federal Constitutions have only skeletal provisions;

- Thirdly, the Indian Constitution has reduced many unwritten conventions of the British Constitution to written principles, for instance, the principle of collective responsibility of the Ministers under Article 75(3) of the Indian Constitution;

- Fourthly, there are various communities and groups in India. Therefore in order to remove mutual distrust among them, it was felt necessary to include in the Constitution detailed provisions in the fundamental rights which will provide safeguards to minorities, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Backward Classes;

- Fifthly, to ensure that the Indian structure is based on the concept of social welfare, the Indian Constitution included directive principles of state policy. The directive principles of state policy describes the aims and objectives to be taken up by the State in the governance of the country; and

- Lastly, the Indian Constitution contains not only the fundamental principles of governance but also many administrative details such as provisions relating to citizenship, official language, government services, electoral machinery, etc. Due to the vast Indian population with varied cultural diversity, the need was felt to provide separate provisions to avoid confusion and also for proper administrative functioning.

Preamble

The Preamble of the Constitution lays down its source, aims, objectives, the nature of the polity established by it and the sanctions behind the sources. The Preamble does not grant any power to the Constitution but only gives a direction and purpose to the Constitution. The Preamble contains the fundamentals of the Constitution. India is declared to be a Sovereign, Socialist, Secular, Democratic, and Republic in the Preamble of the Constitution. The term ‘Sovereign’ was incorporated in the Preamble of the Indian Constitution to provide supreme power to the government. The principle of ‘Sovereignty’ is the backbone of our Indian Constitution that protects the authority of the people.

By the 42nd Amendment Act of the Constitution in 1976, the term “socialist” was added to the Preamble. It means some form of ownership of the means of production and distribution by the State. The degree of State control determines whether it is a democratic state or a socialist state. This term does not mean total exclusion of private enterprise and complete own enterprise and complete state ownership of material resources of the nation. The term ‘secular’ was not originally present in the Preamble. It was added by the 42nd Constitutional Amendment in 1976. The state does not identify itself with, or favour, any particular religion. The state is enjoined to treat all religions and religious sects equally.

The Indian Constitution is adopted, enacted, and brought into force by the people for themselves. It establishes mechanisms for a representative democracy, defined as government by the people, for the people, and of the people. This implies that the citizens of a democratic country can elect their government, which is accountable and answerable to them. Democratic principles are strengthened through universal adult franchise, regular elections, fundamental rights, and a responsible government. The term “republic” refers to a state where supreme power resides with the people and their elected representatives. Unlike a monarchy, where the head of state is a hereditary monarch, a republic has an elected head of state. Sovereignty rests with the people, and the head of state is chosen for a fixed term. All public offices, from the highest to the lowest, are accessible to all citizens without discrimination. The Preamble designates India as a republic with this principle in mind.

Ordinarily, the Preamble was not regarded as a part of the statute. Therefore, at one time, it was thought that the Preamble did not form part of the Constitution as was held in the case of In Re Berubari Union and Exchange of Enclaves (1960). But that view is no longer in existence. In the 13 judges bench of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Kesavananda Bharati vs. State of Kerala (1973), it has been laid out that the Preamble is indeed a part of the Constitution. The majority of judges opined that any provision of the Indian Constitution can be amended by the Parliament, provided that such an amendment did not change the basic structure of the Indian Constitution.

Unique blend of rigidity and flexibility

The Indian Constitution is neither rigid nor flexible, for this reason it makes our Constitution the lengthiest one. A rigid Constitution can be defined as one that needs a special method of amendment of any of its provisions. According to A.V. Dicey, a “rigid constitution” means it cannot be changed in the same manner as ordinary laws. In the case of a flexible Constitution, any of the Constitutional provisions can be amended by the ordinary legislative process.

A written constitution is generally considered a rigid one since it is difficult to change the written words. However, the Indian Constitution, even though written, is sufficiently flexible. Article 368(2) of the Indian Constitution provides that in certain cases the consent of half of the State Legislatures is required for the amendment to take place. The rest of the provisions can be amended by a special majority of Parliament.

A famous example of a rigid constitution is the Constitution of the United States, and it is known as a rigid constitution as the amendment process is very difficult. The Indian Constitution is not as difficult to amend, as the Constitution of the United States. The Indian Constitution has gone through 106 amendments till date. Hence, it can be said that the Indian Constitution is a unique blend of rigidity and flexibility.

Federal Constitution

The Constitution of a country may be federal or unitary in nature. In a federal Constitution, there exists a Central Government that has certain powers that it exercises over the entire country and these supersede the powers of the states. Then there are State Governments and each government has jurisdiction within a State which cannot be superseded by the Centre. The Constitution of India is neither federal nor unitary. Therefore, India is an example of a quasi-federal Constitution.

A federal Constitution is a much more complicated document than a unitary Constitution because it provides for distribution of legislative powers between Central and the State Governments, administrative and financial powers between the Central and State Governments which a unitary Constitution is not concerned with. Within a federal framework, the Indian Constitution provides for a good deal of centralisation. The Central Government has a large sphere of action and thus plays a more dominant role than the States. List VII of the Seventh Schedule of the Indian Constitution contains subjects of common interest to both the Centre and the States.

The reasons for calling the Indian Government unitary are as follows:

- The division of powers is not equal. The Union Government has more powers than the State Government, which could be determined from the fact that the Union list contains more matters than the State list;

- In federations like the U.S.A., the states have the right to frame their own constitution, which is not possible in India as the entire country follows a single constitution;

- During the time of emergency, the states come under the control of the Centre. The emergency provisions provide a simple way of transforming the normal federal fabric into an almost unitary system so as to meet national emergencies effectively;

- Article 312 of the Indian Constitution provides for All-India Service. It allows the Parliament to create one or more All-India Services that are common to both the Union and States;

- The Governor of a State is appointed by the President of India under Article 155 of the Indian Constitution;

- Article 324 of the Indian Constitution discusses the Election Commission of India in which the supreme authority rests with the President of India for election-related matters;

- The Comptroller and Auditor General of India is also appointed by the President of India under Article 148 of the Indian Constitution.

The Indian Constitution is considered as federal for various reasons like:

- There is a written Constitution which is an essential feature of every country following the federal system;

- The supremacy of the Constitution is always protected;

- Schedule VII of the Indian Constitution distributes the law-making power between the Central and State Governments; and

- Articles 214 to 231 provide for High Courts in the States and Articles 233 to 237 provide for Subordinate Courts;

Thus, the Indian Constitution can be described as “quasi-federal” or a federation with a strong centralising tendency. A “quasi-federal” constitution refers to a type of constitutionalism where power is not evenly distributed between the centre and the states. India is considered a federation with a unitary bias, which is why it is described as a quasi-federal state due to its strong central governance.

Adult suffrage

The concept of adult suffrage allows every citizen of our country who is above the age of eighteen years to have the right to vote in the elections. Article 326 of the Indian Constitution guarantees this right to all the adults in the nation. This provision was added by the Constitution (Sixty-first Amendment) Act, 1988. The accepted age for voting was twenty-one before this amendment; afterwards, it was changed to 18 years of age.

It may be correct to say that the right to vote is neither a common law right nor a fundamental right. However, it is also not a mere statutory right but it holds more substantive significance. The right to vote is not just a privilege granted by the Legislature but it is also enshrined in the Indian Constitution. It can be said so because of the following reasons:

- Firstly, free and fair elections have been declared to be a basic feature of the Constitution in the case of Indira Nehru Gandhi vs. Shri Raj Narain and Anr. (1975). It means that no statute can completely negate the right to vote;

- Secondly, the right to vote is a constitutional right as enshrined under Article 326 of the Indian Constitution. Any individual attaining the age of eighteen years is “entitled” to vote. Article 325 provides that no voter can be debarred from voting “on grounds only of religion, race, caste, or sex.” Further, this means that any statute passed by a legislature to regulate the right to vote has to fall within the parameters set out by Articles 325 and 326. Any law infringing these parameters will be void;

- Thirdly, Articles 84(b) and 173(b) grant the right to stand for election. The essential qualification that allows individuals aged twenty-five years or older to contest for a seat in the Lok Sabha or State Assembly and not less than thirty years of age in the case of a seat in the Rajya Sabha or Council of States. While statutes can establish specific qualifications and disqualifications for candidates [Articles 102(1)(e) and 190(1)(e)] and set procedural rules for filing nomination papers, they cannot entirely negate the qualification required under Articles 84 and 173; and

- Fourthly, the right to challenge an election through an election petition is conferred by Article 329(b) and is, thus, a constitutional right. What remains for the legislature to do is to prescribe the forum and procedure for deciding the election petitions. No legislature can refuse to set up any machinery for deciding election petitions.

Independence of Judiciary

The judiciary in India has been assigned a significant role to play. Indian courts have been vested with the duty to dispense justice in the matters of not only of an individual but also with respect to the disputed states and its citizens. It interprets the Constitution and the other laws of the country acts as its guardian by keeping all authorities namely legislative, executive, administrative, judicial and quasi-judicial authorities within bounds. The Indian judiciary is entitled to scrutinise governmental action in order to assess whether or not it conforms with the Constitution and the basic structure governing the nation. The judiciary supervises the administrative processes in the country and acts as the balance wheel of federalism by settling intergovernmental disputes.

The judiciary has the power to protect people’s Fundamental Rights from any undue encroachment by any organ of the government. The Hon’ble Supreme Court, in particular, acts as the guardian and protector of the Fundamental Rights of the people. A person complaining of a breach of his Fundamental Rights can directly invoke the writ jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and High Court under Articles 32 and Article 226 of the Constitution respectively. To enable the Hon’ble Supreme Court and various High Courts to discharge their functions impartially, without fear or favour, the Constitution contains provisions to safeguard judicial independence.

The judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts are appointed by the President on the advice of the judges themselves. Once appointed, the judges shall hold office till the age of superannuation as fixed by the Constitution. Under Articles 124 and 217, a special procedure has been laid down for removing the judges on the grounds of incapacity or misbehaviour.

Single Citizenship

Part II of the Indian Constitution, i.e. Article 5 to Article 11 of the Indian Constitution deals with citizenship. There is no separate citizenship for the States and the Centre in India like in various federal countries like the U.S.A. There is single citizenship provided to Indian citizens. Single citizenship allows persons to enjoy equal rights in various aspects across the country.

According to Article 5, it is clearly mentioned that the persons will be considered as citizens of the territory of India, which ensures that there would be only single citizenship. The citizenship of Indians is largely determined by the principle of jus sanguinis, i.e., the citizenship is based on the citizenship of the parents. In single citizenship, a person holds only one citizenship. On the contrary, in the case of dual citizenship, each person is a citizen of both the Centre and State.

Judicial Review

The concept of judicial review is an essential feature of the Indian Constitution which helps the Constitution to work properly. Article 13 provides for “judicial review” of all previous and future legislation in India. It is the function of the courts to assess laws and statutes in place vis-a-vis the Fundamental Rights so as to ensure that no law infringes the basic structure. The courts perform the arduous task of declaring a law unconstitutional if it infringes a Fundamental Right.

In the case of Kesavananda Bharati Sripadagalvaru and Ors. vs. State of Kerala and Anr. (1973) and Minerva Mills Ltd. and Ors. vs. Union of India and Ors. (1980), the Hon’ble Supreme Court strengthened its protective role under Article 13(2) by laying down the proposition that judicial review is the ‘basic’ feature of the Constitution. This means that the power of judicial review cannot be curtailed or evaded by any future Constitutional amendment. Several Articles in the Constitution, such as Articles 32, Article 136, Article 226 and Article 227, guarantee judicial review of legislative and administrative action.

It is also a settled principle that there should be no judicial review in policy matters, and that the policy decision taken by the State or its authorities is beyond the scope of judicial review. It shall not be done unless the decision is found to be arbitrary, unreasonable or it is in contravention of the statutory provisions or if it violates the rights of individuals guaranteed under the statute. The policy decision cannot be in contravention of the statutory provisions because if the Legislature in its knowledge provides for a particular right, the authority making a decision regarding the policy cannot nullify the same. The same principle was also articulated in the case of Monarch Infrastructure (P) Ltd. vs. Commissioner, Ulhasnagar Municipal Corporation (2000). In this case, it was said that the court would not interfere in the matter of administrative action or changes.

Landmark Judgements on Judicial Review

- In Marbury vs. Madison (1803), the Hon’ble U.S. Supreme Court established that legislative actions can be reviewed by the judiciary, despite the absence of a specific constitutional provision for judicial review in the U.S. Constitution.

- In Kesavananda Bharati vs. State of Kerala (1973), the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that while Parliament is not restricted in its power to amend the Constitution, it must adhere to the doctrine of the basic structure. The court also emphasised that the constitutional amendments must respect the fundamental framework of the Constitution.

- In A.K. Gopalan vs. the State of Madras (1950), it was held by the Hon’ble Supreme Court that the laws regarding preventive detention are subject to limited judicial review.

- In V.G. Row vs. State of Madras (1950), the Hon’ble Madras High Court discussed judicial review as a limitation on legislative supremacy, asserting that it is a fundamental component of the constitutional framework. The court’s role is to declare laws void if they violate constitutional provisions.

- In Binoy Viswam vs. Union of India (2017), the scope of judicial review of legislative actions was examined in detail.

- In Shayara Bano vs. Union of India (2017), the Hon’ble Supreme Court held judicial review must be practised by looking into social values and should be interpreted according to the changing social needs.

- In L.Chandra Kumar vs. Union of India (1997), the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that the power of judicial review exercised by the Hon’ble High Court under Article 226 cannot be excluded by a constitutional amendment.

- In Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay) Pvt. Ltd. and Ors. vs. Union of India and Ors. (1984), the Hon’ble Supreme Court reviewed subordinate legislation, noting that such legislation does not enjoy the same immunity as statutes enacted by a competent legislature.

- In State of Tamil Nadu vs. P. Krishnamoorthy (2004), the Hon’ble Madras High Court established various criteria for the purposes of judicial review of the subordinate legislation.

Parliamentary form of Government

The Indian Constitution establishes a parliamentary form of Government both at the Centre and State level to give effect to the democratic ideals propounded in the Preamble. The bicameral legislature system is followed in our country. The unicameral legislature system is followed in countries like Norway. In this type of legislative system, there exists only one house or assembly. In a Bicameral legislature system, the legislative system is divided into two houses or assemblies. The law-making procedure is easy in the unicameral legislature as compared to the bicameral legislature. There would be a lot of discussions and deliberations before making legislation in bicameralism.

Articles 74 and Article 75 are concerned with the Parliamentary system at the centre. Article 74 of the Indian Constitution provides that there should be a Council of Ministers with the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers can aid and advise the President. Article 75 of the Indian Constitution deals with the other provisions relating to the appointment of Ministers. Articles 163 and Article 164 are concerned with the Parliamentary system in the states. Article 163 provides that there shall be a Council of Ministers with the Chief Minister at the head to aid and advise the Governor at the time of discharging his duties. Article 164 provides that the Chief Minister shall be appointed by the Governor and other Ministers shall be appointed by the Governor on the advice of the Chief Minister. The Ministers shall hold office at the pleasure of the Governor.

Parliamentary vs. Presidential form of Government

The Presidential form of Government is followed in countries like the United States of America. The President is the head of the State in the Presidential System of Government. The Parliamentary system is a democratic type of government. In this system, the party with the majority forms the government. The parliamentary system is preferred over the Presidential system as it ensures the equal distribution of power and also power is not within the hands of a single person. The drafters of our Constitution did not prefer the presidential system as the executive and legislatures would become independent of each other.

Separation of powers

India focuses on separation of functions rather than a strict separation of powers, unlike in the US. While the strict doctrine of separation of powers is not rigorously applied in India, a system of check and balance is in place. This ensures that the judiciary has the authority to invalidate any laws passed by the legislature that are deemed unconstitutional.

Fundamental rights

Part III of the Indian Constitution guarantees certain fundamental rights to the citizens of India. The fundamental rights are a necessary consequence of the declaration in the Preamble to the Constitution that the people of India have solemnly resolved to constitute India into a sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic, republic and to secure to all its citizens justice, social, economic, and political; liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship; equality of status and opportunity. The Fundamental Rights outlined in the Indian Constitution are as follows:

- Right to equality: The right to equality is guaranteed under Article 14 of the Indian Constitution. Article 14 is applicable not only to citizens but also to non-citizens, corporations and foreigners. According to this Article, it is the duty of the state not to deny any person equality before the eyes of the law and to provide them equal protection of laws within the territory of India.

- No discrimination on the grounds of religion, etc.: Article 15 is a particular aspect of equality guaranteed by Article 14 and grants the right to be free from discrimination regarding rights, privileges, and immunities associated with citizenship. Thus, Article 15 forbids discrimination.

- Equality of Opportunity in Public Employment: Article 16 guarantees equality of opportunity to all citizens in matters relating to “employment” or “appointment to any office” under the state and the prohibition of discrimination guaranteed by Article 15(1) in matters of public employment.

- Abolition of Untouchability: Article 17 of the Indian Constitution abolishes untouchability and practising it in any form is forbidden. In Sastri Yagnapurushdasji. vs. Muldas Bhundardas Vaishya and Anr. (1959), it was held that ‘untouchability is founded by superstition, ignorance, and complete misunderstanding of the true teachings of Hindu religion’.

- Abolition of titles: Article 18 of the Indian Constitution abolishes the titles. It prohibits the state from conferring any “title” except a military or academic distinction. According to this Article, no Indian citizen can accept the titles from any foreign states.

- Right to Freedom: Article 19 is the backbone of Part III of the Indian Constitution. This Article guarantees to the citizens of India the enjoyment of certain civil liberties while they are free. Freedoms secured under Article 19 can be claimed only by the citizens.

- Protection in respect of conviction for offences: Article 20 provides protection in respect of conviction for offences.

- Protection of Life and Personal Liberty: Article 21 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the protection of life and liberty. Article 21 is an important right that protects citizens and non-citizens.

- Right to Education: Article 21A guarantees the right to free and compulsory education to children aged 6 to 14 years. This provision was added by the Constitutional (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002. Article 21A makes it obligatory for the Government to enact a Central legislation to give effect to the constitutional amendment.

- Protection against arrest and detention in certain cases: Article 22 provides for preventive detention laws. The object of preventive detention law is to prevent a person from committing a crime and not to punish him as is done under punitive detention.

- Prohibition on Human trafficking and forced labour: Article 23 provides the prohibition of trafficking of human beings and forced labour by humans of any kind.

- Prohibition of employment of children in factories, etc.: Article 24 prohibits the employment of children below fourteen years of age in factories, mines or any other hazardous form of employment.

- Freedom to Profess or Practice Religion: Article 25 provides the Freedom of conscience and free profession, practice and propagation of religion. The concept of the secular state provided under the Preamble is supported by this Article.

- Freedom to manage religious affairs: Article 26 provides the freedom to manage its own religious affairs.

- No taxation to promote a religion: Article 27 guarantees the freedom to pay taxes for the promotion of any particular religion. To maintain the secular character of the Indian polity, not only does the Indian Constitution guarantee freedom of religion to individuals and groups, but it is also against the general policy of the Constitution that any money be paid out of the public funds for promoting or maintaining any particular religion.

- Restriction on religious instruction in educational institutions: Article 28 guarantees the freedom to attend religious instruction or religious worship in certain educational institutions. According to this Article, any person attending any educational institution recognized by the State or receiving aid from State funds can be forced to be a part of any religious instruction provided at the institution.

- Protection of interests of minorities: Article 29 protects the interests of minorities.

- Right of a minority to establish educational institutions: Article 30 provides minorities with the right to establish their own educational institutions and the State shall not discriminate against any such minority institution while providing grants.

- Right to Constitutional Remedies: Article 32 guarantees the right to constitutional remedies. There are various constitutional remedies allowed under this Article in the form of writs. If there is any violation of fundamental rights, the aggravated person can approach the Supreme Court under the rights provided by this Article.

Directive principles of state policy

Part IV (Article 36-51) of the Indian Constitution deals with the directive principles of state policy. It is the duty of every State to apply these principles while making any new legislation. The directive principles of state policy is similar to the ‘Instrument of Instructions’ that is in the Government of India Act, 1935. They are basically instructions to the legislature and executive that have to be followed while framing new legislation by the State. Article 36 provides that the word ‘state’ used in Part IV has the same meaning as has been given to it in Article 12 for the purpose of enforcement of fundamental rights unless the context otherwise requires.

These directions lay down the lines on which the State, which includes both the Legislature and the Executive and means the Union as well as the State should work under the Constitution. The principles express the salient features of the conception of the Constituent Assembly about the new social and economic order which is wanted to bring about through the Constitution. The idea of a welfare State envisaged by our Constitution can only be achieved if the State endeavours to implement it with a high sense of moral duty.

In the Kesavananda Bharati case, the Hon’ble Supreme Court has held that there is no conflict between the directive principles and the fundamental rights and both are supplementary and complementary to each other. Both Part III and Part IV of the Indian Constitution have to be balanced and harmonised together, then only the dignity of the individual can be achieved.

Fundamental duties

Article 51A of the Indian Constitution provides various fundamental duties. The Constitution (Forty-Second Amendment) Act, 1976 introduced the innovative concept of Fundamental Duties of the Indian Citizens in the Constitution. There are no specific provisions to enforce fundamental duties in the courts like the fundamental rights but it is also necessary to follow the fundamental duties. It was held in the case of AIIMS Students Union vs. AIIMS and Ors. (2002), by the Hon’ble Supreme Court that fundamental duties are as important as fundamental rights. There are various duties to be followed by a citizen of India are:

- To respect the Constitution, and its principles and to adhere to the constitutional provisions;

- To cherish and follow the noble ideals which inspired our national struggle for freedom;

- To uphold and protect the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India;

- To defend our country when needed and to provide national service when required;

- To promote harmony and the spirit of common brotherhood;

- To value the rich heritage of our country;

- To protect the environment and carry out measures to improve them;

- To advance scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of fairness and reform;

- To protect the property of the public;

- To strive towards excellence in all spheres of individual and collective, so that the nation constantly rises to higher levels of endeavour and achievement;

- Parent or guardian to provide opportunities for education to his child or, as the case may be, ward between the age of six and fourteen years.

Article 51A pertains exclusively to the citizens of India, unlike some of the fundamental rights, such as Articles 14 and 21, which apply to all the individuals regardless of their citizenship status.

Borrowed from various sources

| Serial No. | Sources | Features Borrowed |

| Government of India Act, 1935 | Federal scheme, Office of governor, Judiciary, Public Service Commissions, Emergency Provisions, and administrative details. | |

| British Constitution | Parliamentary government, Rule of Law, Legislative procedure, Single citizenship, Cabinet system, Writs, Parliamentary privileges, and Bicameralism | |

| US Constitution | Fundamental rights, Independence of judiciary, Judicial Review, Impeachment of the President, Removal of the Supreme Court and High Courts judges and of the Vice-President. | |

| Irish Constitution | Directive Principles of State Policy, Election of members of Rajya Sabha, Method of election of President. | |

| Canadian Constitution | Federation with a strong centre, Residuary powers of the Central Government, Appointment of State Governors by the Centre, and Advisory jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. | |

| Australian Constitution | Concurrent List, Freedom of trade, commerce and intercourse, and Joint sitting of the two Houses of Parliament. | |

| Weimar Constitution of Germany | Suspension of fundamental rights during Emergency. | |

| Soviet Constitution (USSR, not Russia) | Fundamental Duties and the ideal of justice (social, economic and political) in the Preamble. | |

| French Constitution | Republic and the ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity in the Preamble. | |

| South African Constitution | Procedure for Constitutional Amendment. | |

| Japanese Constitution | Procedure established by law. |

Emergency provisions

Emergency provisions in India are constitutional measures that allow the President to take exceptional actions during the time of emergency. These provisions are provided in detail in Articles 352, 354, and 360 of the Indian Constitution. These provisions shift the federal system towards a more unitary form. During an emergency, the Central Government attains more powers and authority towards the states.

Rule of law

“Rule of law” is an animation of natural law and remains a historical ideal which makes a more powerful appeal even today to be ruled by law not by a powerful man. It is generally understood as a doctrine of “state political morality” which concentrates on the rule of law in securing a “correct balance” between “rights” and “powers”, between individuals, and between individuals and the State in any free and civil society. It balances the needs of society and the individual.

Conclusion

The Indian Constitution has a lot of salient features which make it special. The lawmakers have taken all the factors into consideration and have tried to accommodate all the differences in our Country. The Constitution and various rights provided in the Constitution act as a guardian to our citizens. A nation’s Constitution fulfils various roles and establishes principles that shape society. It also symbolises the country’s independence. The Indian Constitution outlines the framework and structure for governing a free nation. It is through the salient features of the Indian Constitution, rules and procedures, consensus is built amongst diverse groups of people and different communities. Constitutional features and rules decide the fortune of a country. These prescribe certain ideals that the country should uphold. In the context of our country, the core values and visions reflected in the Preamble, Fundamental Rights, directive principles of state policy and Fundamental Duties are expressed as objectives of the Constitution.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Who is the father of the Indian Constitution?

The father of the Indian Constitution is Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar. He was the Law Minister at the time, who presented the final draft of the Constitution to the Constituent Assembly.

Can fundamental rights be waived?

In the case of Basheshar Nath vs. The Commissioner of Income Tax (1958), it was held by the Hon’ble Supreme Court that a fundamental right being in the nature of a prohibition addressed to the State cannot be waived by an individual. The Hon’ble Supreme Court opined that the fundamental rights enshrined in the Indian Constitution are not solely for individual benefit but are also a matter of public policy. It is an obligation imposed upon the State by the Constitution. No person can relieve the State of this obligation, because a large majority of the Indian citizens are economically poor, educationally backward and politically not conscious of their rights.

What is the difference between sovereignty and independence?

Sovereignty pertains to a state’s supreme authority to self-govern without external interference, whereas independence signifies the state being free from the control of another country.

What is the difference between Articles 19 and 21?

In the case of A.K. Gopalan vs. State of Madras. Union of India (1950), the Hon’ble Supreme Court made the following distinctions between the two Articles:

- Articles 19 and 21 deal with different subjects. Article 19 deals with “restrictions” on personal liberty. Article 21 deals with its “deprivation”;

- Article 19 is available to citizens only, Article 21 is available to both citizens and non-citizens;

- The liberties guaranteed under Article 19 cannot be enjoyed if a person has lost the freedom of his person by being lawfully detained under Article 21;

- The validity of a deprivation by law under Article 21 cannot be judged under the test prescribed in Article 19(5). Article 19 does not apply to a law of preventive detention even though as a result of an order of detention the rights of a citizen under Article 19 may be restricted or abridged.

In Maneka Gandhi’s case, the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that a law that restricts a person’s personal liberty and establishes a procedure for doing so, under Article 21, must also comply with one or more of the fundamental rights guaranteed by Article 19.

References

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/freedom-speech-expression/

- https://www.india.gov.in/sites/upload_files/npi/files/coi_part_full.pdf

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/right-equality-article-14/

- “Constitutional Law of India” by Dr. J.N. Pandey

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/fundamental-rights-under-the-indian-constitution-a-comprehensive-guide-with-case-laws/#:~:text=Classification%20of%20fundamental%20rights&text=Right%20against%20exploitation%20from%20Articles,by%20Articles%2032%20to%2035.

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/fundamental-duties-2/

- https://blog.ipleaders.in/directive-principles-state-policy/

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals, and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Serato DJ Crack 2025Serato DJ PRO Crack

Allow notifications

Allow notifications